Executive summary

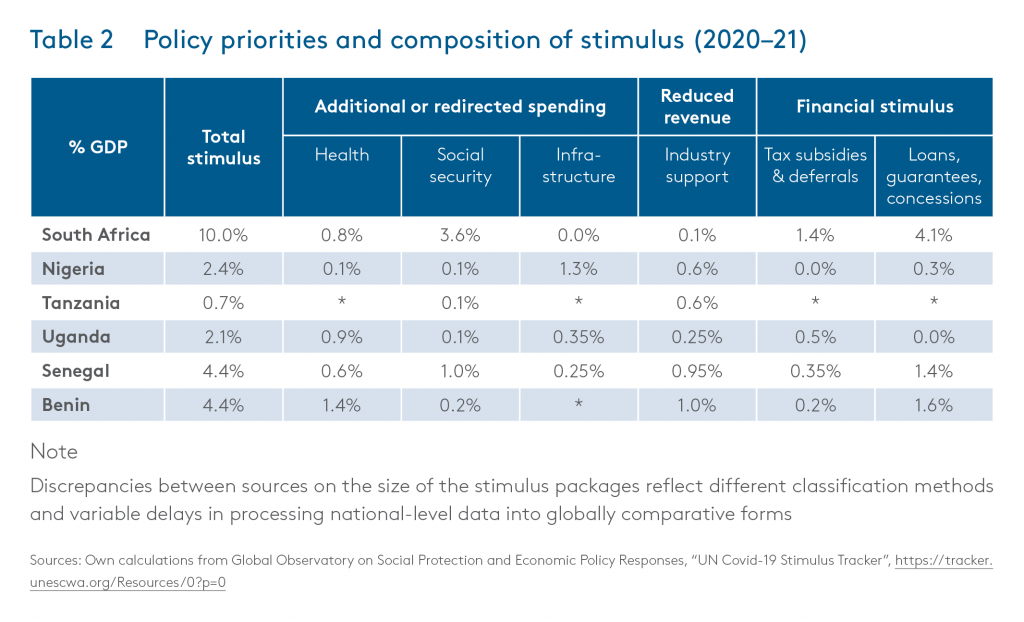

This policy insight synthesises the findings of six sub-Saharan African country case studies, analysing their government policy responses to the trade and employment shocks prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Vulnerability to the shock was most pronounced in the wealthier, more open, diversified and formalised economies (South Africa and Senegal); in Nigeria, where trade and government balances are very sensitive to oil price fluctuations; and in Uganda, which reacted with a strict domestic lockdown. By contrast, growth decelerated only marginally in Benin and Tanzania, where government reactions were minimal or delayed. The capacity to offer a counter fiscal stimulus, liquidity support through loan guarantees and concessional debt, and an accommodative monetary policy depends on the income status of the economy, depth of financial markets, size of the government sector, and access to global development finance channels. South Africa and Senegal were able to put into effect the most substantive stimulus packages, while Nigeria was constrained by having the smallest and most volatile tax base and a high bank liquidity profile. Save for Benin and Uganda, which devoted half their stimulus package to health spending, most countries concentrated on industry support and tax relief. Here South Africa was an outlier, instead using 60% of its package for unemployment and social security benefits owing to a sharp rise in unemployment and food stress.

The key national policy challenges identified for the COVID recovery period include extending food security nets, adjusting infrastructure and industrial policy to accommodate climate risk mitigation and adaptation, removing intra-African tariffs and standardising non-tariff barriers to reinvigorate African economies, and diversifying government revenue bases. Key global policy initiatives requiring a common African negotiating position pertain to persuading higherincome nations to donate their excess Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocations to the relevant International Monetary Fund (IMF) facilities that on-lend concessional finance to bolster central bank reserve adequacy and boost development finance flows. The potential for a global debt restructuring initiative is explored, with a focus on official development aid (ODA) for food security.

Economic development context

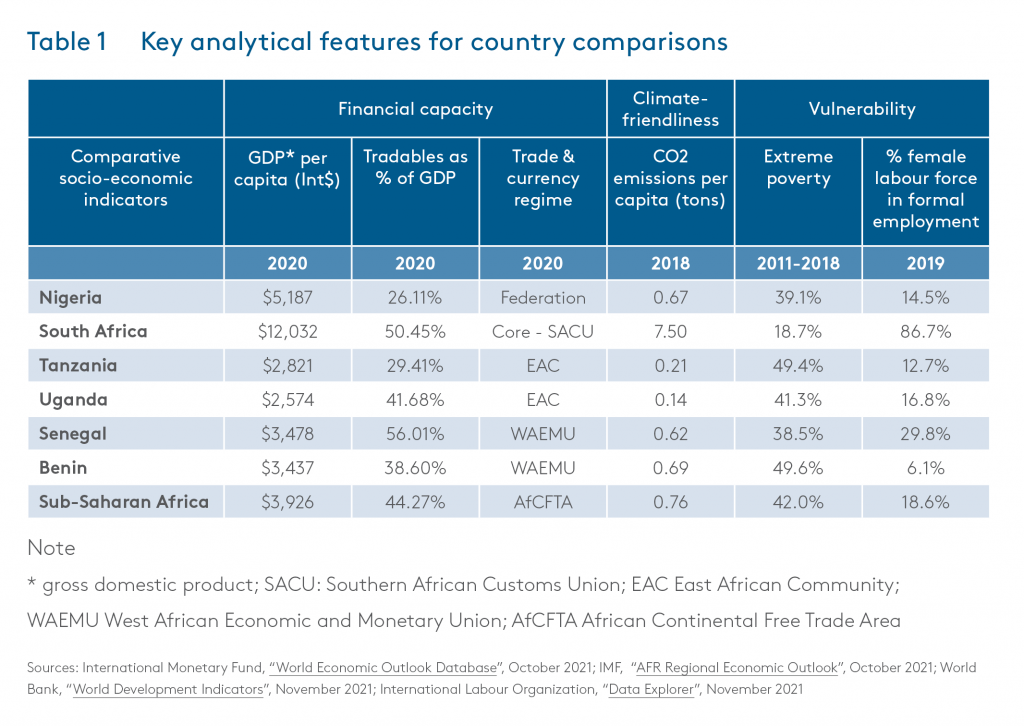

This policy insight is a synthesis of case studies of six middle- and low-income countries across sub-Saharan Africa, investigating the impact of, and policy responses to, the COVID shock of 2020–21. It also evaluates them against longer-term developmental objectives of social inclusivity and climate resilience. Comparative data analysis is undertaken with a view to developing financial capacity, climate-friendliness and vulnerability–inclusivity indices. Policy recommendations are guided by the question of how to develop Africa’s resilience to shocks through the COVID recovery period (2021–2024) and beyond.

Key country features

South Africa is sub-Saharan Africa’s (SSA) richest major economy with per capita incomes three times the sub-continental average. Roughly 85% of its labour force is dependent on formal sector employment, and the formal unemployment rate is 35%. It is the only major African nation where gender parity in both formal and informal employment status is evident. As indicated by carbon emissions that are 10 times the sub-continental average, South Africa is also the most pervasively industrialised economy, but with legacy infrastructure that needs replacing or renovating. It has a large services sector, contributing 61.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020, compared to the SSA average of 48%. Finance, trade, information and communications, and government services are more important contributors to value added than elsewhere on the sub-continent. Its financial markets are considerably deeper (offering a range of longer-term – including green – financial products unavailable elsewhere in SSA) and wider (with banking penetration rates nearly double the SSA average). The country has an independent currency that exchanges freely on global markets, and is the core of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU).1Palesa Shipalana, “Macroeconomic Policy Development: Lessons Learnt from South Africa during COVID-19” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 1, South African Institute for International Affairs, Johannesburg, May 26, 2021).

Nigeria is SSA’s largest economy but, like most of the case study countries, is classified by the World Bank as lower-middle-income.2The World Bank defined lower-middle income as per capita gross national income of between $1,045 and $4,125 at 2015 prices. In contrast to South Africa, but in common with the rest of the sub-continent, only about 20% of its labour force is employed formally, and there is a clear employment gender bias in favour of men. Owing to the subsistence nature of most informal employment, extreme poverty rates across SSA are more than double those of South Africa. The composition of value added is relatively typical of the sub-continent at 25% each to agriculture and industry and 50% to services. Of the case study countries, Nigeria is the least open to international trade and the most protectionist of domestic producers (with consequently high tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade). It is a member of the ECOWAS free trade agreement and has an independent currency with a fixed peg – a situation that is difficult to sustain. Nigeria’s financial markets are also relatively shallow. Banking penetration rates are below average, and credit offerings are predominantly short term and operational. Liquidity ratios are unusually high and loan-to-deposit ratios unusually low. The country has a small public sector with spending and revenue respectively constituting 12.1% and 6.3% of GDP in 2020. Balance of payments and government balances are unusually vulnerable to fluctuations in oil prices despite (or because of) protectionist policies.3Mma Amara Ekeruche and Adedeji Adeniran, “Lessons for Macroeconomic Policy from Nigeria amid the COVID-19 Pandemic” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 2, Johannesburg, SAIIA, July 22, 2021).

Senegal and Benin are members of WAEMU and share a common currency backed by the French Treasury. This backing offers several developmental advantages for these small economies, including access to concessional debt to maintain trade and investment balances, currency stability, the deepening of financial markets and, with it, the capacity of governments to raise debt finance. Senegal is notably more industrialised and financialised than Benin, with higher rates of formal employment, a lower gender employment gap and lower extreme poverty.4Mouhamadou Fallilou Ndiaye, “COVID-19 and Its Impact on Senegal’s Macroeconomic Structure” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 8, Johannesburg, SAIIA, October 6, 2021); Ian Hefferman, “Macroeconomic Policy Development in Benin” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 9, Johannesburg, SAIIA, December 2021).

The poorest segment in the country case studies cohort is two members of the EAC, Tanzania and Uganda. EAC member countries are broadly similar in terms of composition of value added. They are more agriculture and agro-processing oriented than average, the structure of the labour force has the highest gender employment gaps, and the depth of financial markets is low while the public sector is relatively small. Membership of a customs, and incipient monetary, union is enabled by these similarities and is evidenced by a common restraint in terms of divergences in trade, fiscal and monetary policy.5Oswald Joseph Mashindano and Vivian Kazi, “Macroeconomic Policy Development in Tanzania” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 7, Johannesburg, SAIIA, October 4, 2021); Ibrahim Okumu, Susan Namirembe Kavuma and George Bogere, “Efficacy of COVID-19 Macroeconomic Policy Responses in Uganda” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 6, SAIIA, Johannesburg, September 20, 2021).

Performance and prospects

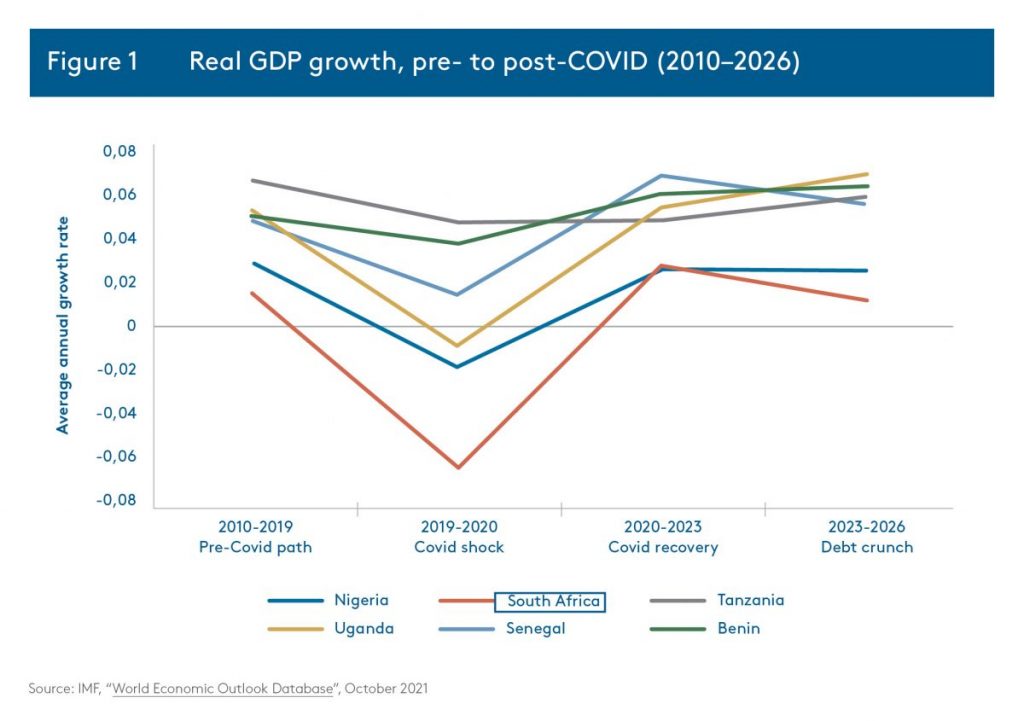

This section reviews the relative impact of the COVID shock on economic livelihoods, and the capacity and willingness of national governments to offer counter-cyclical support at the height of the pandemic in 2020. It also looks at the prospects for the medium-term recovery period (2021–24) and beyond (up to 2026) when Africa could face a debt repayment wall.6African Development Bank, African Economic Outlook 2021: From Debt Resolution to Growth – The Road Ahead for Africa, Report (Abidjan: AfDB, May 2021), 74.

Vulnerability to COVID-induced trade and policy shocks

The COVID shock was transmitted to Africa through disruptions to international trade and global supply chains, amplified, in varying degrees, by domestic restrictions on trade and employment. Thus one might expect the more open economies and those that are formal-employment intensive (notably South Africa and Senegal) to be most deeply and widely impacted.

Structural growth trends are also important in explaining why such divergent economic structures as South Africa and Nigeria were most deeply shocked into recession. Per capita incomes in South Africa have been in structural decline for the past decade, and in Nigeria, low real per capita growth has been prone to commodity price shocks. Poor investor confidence around the energy transition and industrial refurbishment is also relevant in the South African instance. For Nigeria, the main structural constraints appear to be around trade diversification and liberalisation, industrial and agricultural export orientation, and government revenue enhancement.7Ekeruche and Adeniran, “Lessons for Macroeconomic Policy”

Domestic policy differences played a role in amplifying the global supply chain shocks. While Uganda quickly closed its borders and imposed a domestic lockdown, arranged for IMF concessional debt and issued a fiscal stimulus package, Tanzania decided that the (actual and opportunity) costs of lockdowns and stimulus packages were not worth the longer-term debt burdens. Tanzania’s GDP growth decelerated from 6.7% (2010–2019) to 4.8% in 2020; while Uganda’s plunged from 5.3% to -0.8%.8Okumu, Kavuma and Bogere, “Efficacy of COVID-19 Macroeconomic”. Within WAEMU, where intra-regional constraints on trade and fiscal balances are more imposing, Senegal reacted faster and more comprehensively than Benin. Senegal’s growth in 2020 decelerated sharply from 5% to 1.5%, while Benin’s dropped more modestly from 5.1% to 3.8%.9Mashindano and Kazi; “Macroeconomic Policy Development”.

When projecting into the COVID recovery period and the subsequent debt crunch, the IMF uses a return to structural growth trends in the medium term and a variable deceleration thereafter as its basis. Thus, the low-growth, core economies of South Africa and Nigeria, and the highgrowth, semi-peripheral economies of WAEMU and EAC, are expected to rebound accordingly. Certain national policy differences are taken into account. Notably, these include success with the energy transition in South Africa, thereby lifting real per capita growth into the positive and, at the same time, an expectation that Tanzania will suffer the consequences of its COVID denialism. This will see a prolonged recovery, compensated for by a longer-term uptick without the additional debt repayment burden.

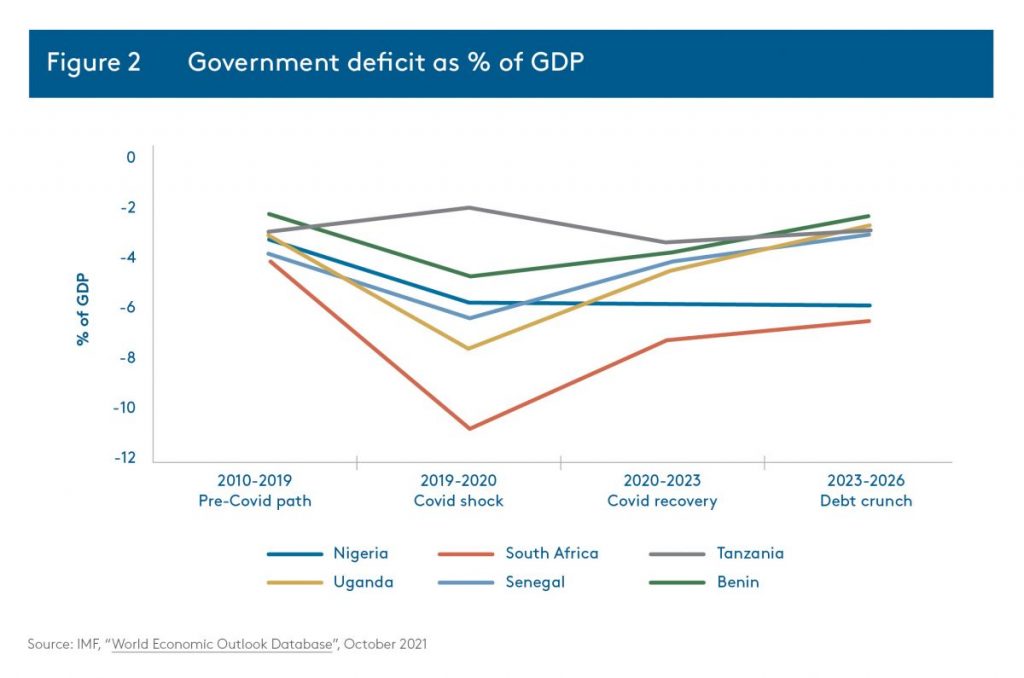

Capacity to effect fiscal stimulus

Whereas one might expect the width and depth of the tax base or access to domestic or foreign credit markets to be the main determinant of fiscal capacity to raise government deficits, this is only partially true (in the cases of South Africa and Senegal). National specificities in policy responses to countering the shock were also important. While Uganda, like South Africa and Senegal, more than doubled its deficit, Tanzania lowered its spending, deficit and debt levels in 2020. While all the other countries managed to sustain or increase their tax-to-GDP ratios, Nigeria’s extra deficit can largely be attributed to a loss of resource tax revenue from 10% (2010–2019) to 6.3% (In 2020).

Inasmuch as Nigeria’s tax losses are the result of depressed commodity prices during 2020, so a reversal of fortunes in 2021 is evident as global supply chain re-openings boost producer demand and prices. This reversal, however, was not foreseen in the IMF’s projections of slow tax growth and spending austerity. In Tanzania, expectations are that delayed spending will raise its low deficits somewhat over the COVID recovery period. Elsewhere, a combination of tax revenue consolidation and spending austerity is expected to return deficits to trend through to 2026.

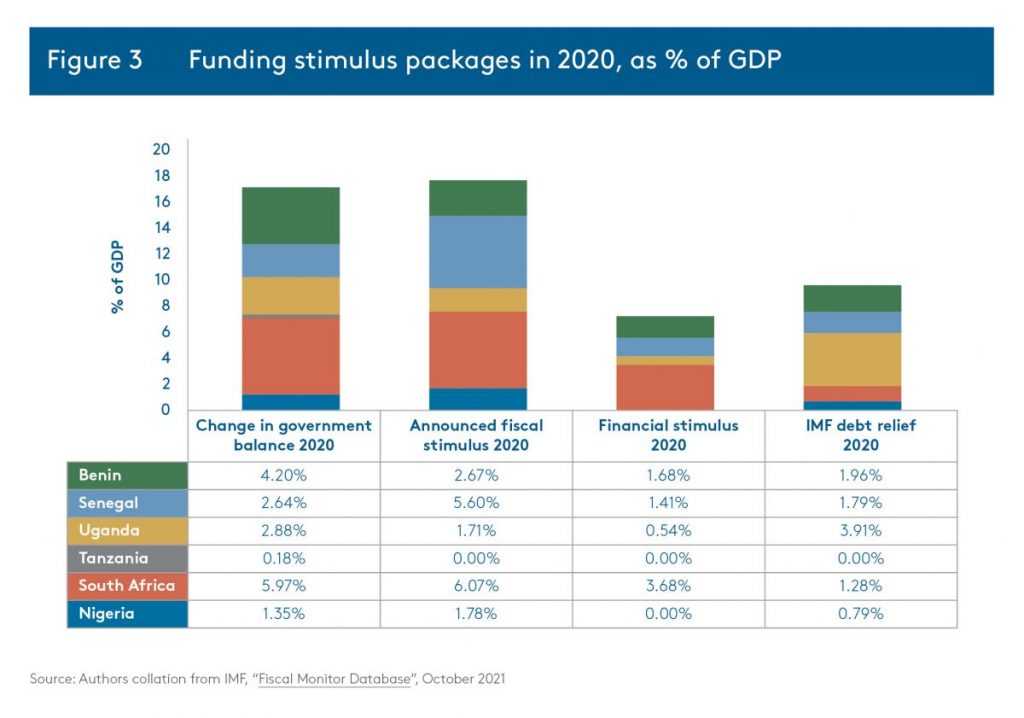

There are some discrepancies between the value of the fiscal stimuli announced and the actual funding that can be released (as indicated in Figure 3). Significant funding gaps are apparent for Senegal and, to a lesser extent, Nigeria. South Africa’s actual and budgeted measures largely corresponded. In Benin, Tanzania and Uganda, stimulus packages were lower in value than the change in government balance. These conservative spending responses reflected uncertainty about the extent of the tax shortfalls that the COVID shock might induce, and the full extent of the counter-cyclical spending required.

Capacity to effect a financial stimulus

Some countries announced financial stimulus (or liquidity support) programmes mainly in the form of short- to medium-term loan guarantees or extensions of concessional loan schemes to stricken (tourism) or priority (industrial or agricultural) sector firms. Countries with deeper financial markets and well-established concessional development finance channels (ie, South Africa and the WAEMU countries) have the greatest capacity to effect financial stimuli. These countries are also able to effectively tap global climate and development financing flows. By contrast, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda will need to extend their financial sector capabilities into capital and insurance products if they are to activate these channels.

Strengthening and activating linkages between global, continental and national concessional finance channels are an integral part of institutionalising any long-term energy transitioning, industrial or agricultural development strategy. Deepening development finance channels can weaken defences against unsustainable debt accumulation. The probabilities of guaranteed loan default, the estimation of implicit interest subsidies and the catalytic effect of direct equity or bond purchases of parastatal and public–private partnership stock are all difficult to measure. Hybrid financial instruments create contingent liabilities (off balance sheet) that lie awkwardly between treasury and central bank remits. As such, they can complicate risk assessments of sovereign creditworthiness if not transparently recorded and actively managed.

To some measure, take-up of these additional contingent liabilities was enabled by access to similarly concessional loans from the IMF. When central banks record less than three months of import cover, full coverage of external short-term debt, and 20% of M2 (cash, savings deposits and money market mutual funds) as a buffer against capital flight, they are eligible for progressively longer maturity, more concessional and conditional debt.

As an upper-middle-income country, South Africa is only eligible for the shortest-term Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) funding, which comes without technical assistance or policy implementation requirements. South Africa is the only case study country that can supplement its financial stimulus packages with own funding. Nigeria has also taken out RFI funding but – seemingly – without the accompanying domestic liquidity support. Senegal, Benin and Uganda have progressed to RCF and Extended Credit Facilities. These are longer-term facilities with commitments or conditionalities relating to social security net extension, capital and liquidity reserves for banks, and public finance management respectively. These country take-ups of concessional debt exceed any announced financial stimulus. Tanzania’s heterodox approach is indicated by a refusal to accept IMF debt.10International Monetary Fund, “COVID-19 Financial Assistance and Debt Service Relief”, June 2021.

Inasmuch as additional debt is required to recover from the COVID shock and build future resilience to shocks, and funds are spent cost effectively in terms of global and national policy objectives, raising the portion of concessional (multilateral or bilateral) official over private debt will ease the prospective debt burden. IMF short-term debt will become repayable within two to five years from 2020 and is expected to contribute to an African debt servicing wall peaking in 2024. As Figure 3 shows, Uganda (with 3.9% of its GDP being IMF funded) is most exposed to this risk, and Nigeria and Tanzania least so.

Capacity to effect monetary stimulus

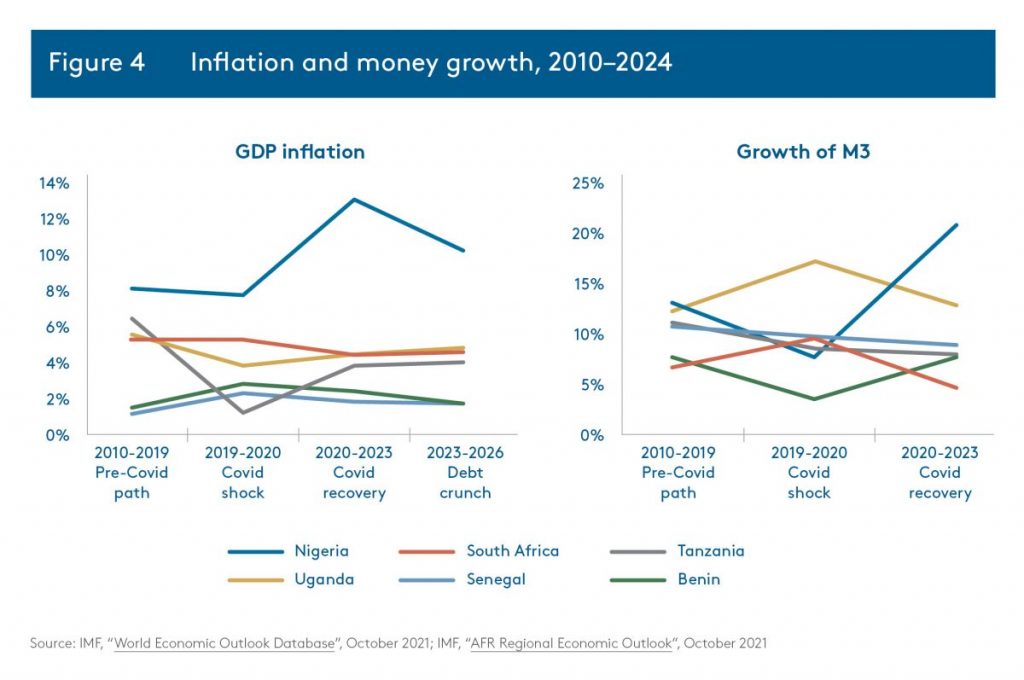

It might be expected that a monetary accommodation will accompany fiscal and financial stimuli. As a government raises its deficit and debt levels, it will need to boost demand for its bonds. It does this by lowering bank reserve requirements, lowering the interest rate from central to commercial banks, and expanding the monetary base. Most of the central banks in our case studies did indeed implement monetary measures in 2020, but only South Africa and Uganda accelerated growth of the money supply in line with their fiscal stimuli. While Tanzania remained unperturbed by the COVID reverberations, money supply growth decelerated in the West African countries. For Senegal and Benin, monetary stimulus is outside their control, as the Central African franc is pegged to the euro. For Nigeria, the concern is that a monetary stimulus will quickly generate domestic inflationary pressures and a depreciation of the independent currency against efforts to stabilise it.11IMF, Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa – Navigating Uncertainty, Report (Washington DC: IMF, April 2021).

Nigeria has structurally higher inflation than the others, and it is expected to rise over the recovery period. South Africa has an independent currency prone to unrestricted depreciation and consequent exposure to imported inflation. However, both the money supply and banking assets as a percentage of GDP (at 86% and 137% respectively in 2020) are much higher than elsewhere on the sub-continent.12IMF, Regional Economic Outlook. This implies a far greater systemic capacity to affect the velocity of circulation and productive capacity utilisation, without causing price increases. As such, the central bank’s inflation targeting has been maintained within its limits of 3–6%, and it is expected to continue doing so through a gradual tightening of its monetary policy stance.13Shipalana, “Macroeconomic Policy Development”. WAEMU countries are expected to contain inflation through external constraints on monetary expansion, while Tanzania is expected to maintain tight monetary policies.

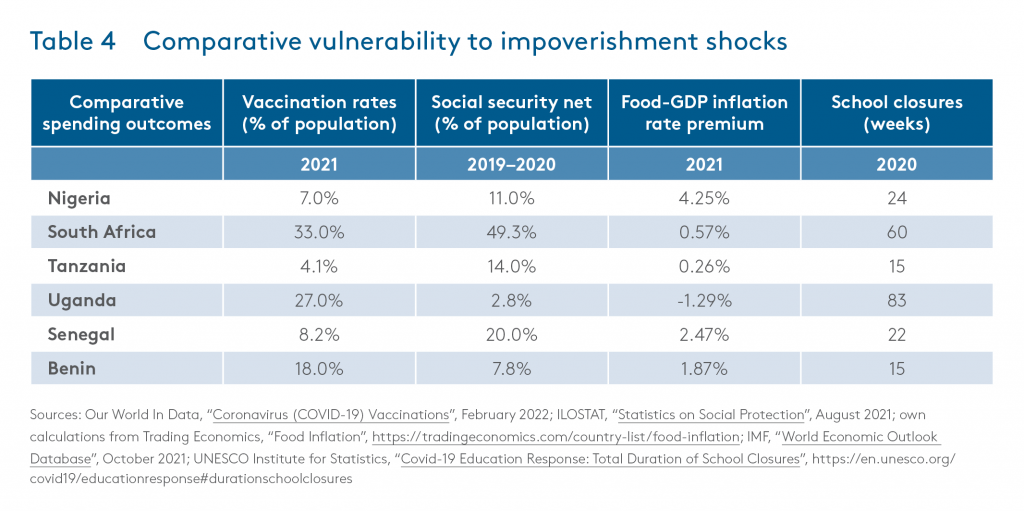

Whether or not demand–pull inflation is induced by accelerated monetary expansion, cost–push inflationary pressures are expected globally and Africa-wide during the recovery. This is owing to supply chain disruptions and restructurings, which tend to accentuate tendencies towards monopolistic supply and distribution channels. While inflation may reduce the real value of debt, it disproportionately affects the real spending power of the poor. Consumer price inflation is usually higher than producer inflation and, with food being the most income-inelastic of commodities, food inflation premiums are even higher. This is especially true for Nigeria, where the premium was an additional 4.3% in 2021. By exception, a food inflation discount of -1.3% is estimated for Uganda, where agricultural input subsidies and freer trade in agricultural commodities are promoted.14Own calculations comparing IMF data on GDP inflation against food price inflation from Trading Economics.

National policy responses

This section reviews the composition of announced stimulus packages as a reflection of both implementation capacity and policy choice in response to a (public health) shock. It evaluates these against the longer-term developmental criteria of building resilience by ensuring inclusivity and enabling the climate transition.

Inclusivity: Employment and poverty

The West African countries devoted approximately one-third of their fiscal stimulus to industry support (salaries and operational costs) while Tanzania’s delayed COVID policy response was largely composed thereof. South Africa and Uganda made substantial use of tax deferrals and subsidies (roughly one-quarter of their packages). Although aimed at protection, these measures disproportionately benefitted business owners and core employees.

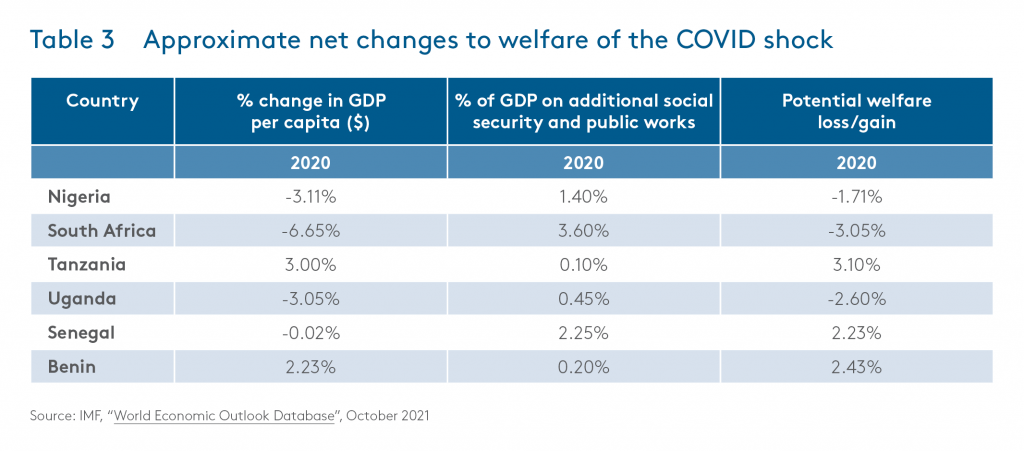

The COVID shock shed formal sector jobs in line with the depth of GDP recession induced. Between the end of 2019 and 2020, unemployment rates rose from 32.6% to 34.4% in South Africa, 27.1% to 33.3% in Nigeria and 16.7% to 22.6% in Senegal.15Trading Economics, “Unemployment Rate”, https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/unemployment-rate In part, this was countered by an expansion and extension of unemployment benefits. South Africa devoted over 60% of its package to extending the social security net, and Senegal about one-third. Both countries introduced new grants for unregistered workers in the informal and domestic sectors in recognition that formal sector job losses swell the ranks of the under-employed, self-employed and unpaid. While Nigeria’s social security net is undeveloped by African standards, the country devoted over half its stimulus package to labour-intensive public works programmes. In the other high-growth East African countries and Benin, where the impact on poverty from trade disruption-induced unemployment was far less pronounced, there were also less capacity and demand to extend social security nets.

A comparison of the changes to per capita GDP from the COVID shock and the proportions of GDP announced as counter-cyclical welfare measures suggests that economies that sustained economic growth (Tanzania and Benin) did not suffer welfare losses. It also suggests that counter-cyclical measures alleviated nearly half the welfare losses in Nigeria and South Africa, and 15% of Uganda’s, and more than compensated for them in Senegal. The compilation of cross-country comparative data on poverty will enable better assessment of the effectiveness of these measures.

The third major component of the fiscal stimulus is health spending. Uganda and Benin allocated about half their packages to health, with underwhelming results in terms of vaccination rates (see Table 4). Senegal devoted a fifth of its package to health, with marginally better effects. South Africa spent a seventh of its stimulus on health quite effectively in terms of vaccination coverage. Nigeria and Tanzania spent and received little.

With slow vaccination rates and rising unemployment and poverty, one can expect that, for the medium term, governments will continue their increased spending on health and social security, unless COVID-19 morphs into an endemic disease in the short term. Coupled with inevitable increases in debt repayment requirements, these fiscal commitments will squeeze out spending on longer-term investments in education and infrastructure, as well as security services that may be needed to keep peace as economic deprivation fuels civil and border conflicts.

Climate transitions

Most country policy responses to COVID have been reactive to the crisis rather than pro-active in either adjusting or fulfilling socio-economic development strategies. Little or no consideration was explicitly given to the energy transition in devising stimulus packages. South Africa delayed its carbon tax implementation schedule (a climate-negative revenue measure) while Nigeria redirected fossil fuel subsidies to public works programmes (a climate-positive spending measure). Elsewhere and otherwise, industry and liquidity support measures can be considered climate neutral or indirectly negative.16Joseph Matola, “Covid-19 Fiscal Policy Responses and Climate Change Action in Africa” (CoMPRA COVID-19 Series Policy Insight 9, SAIIA, Johannesburg, November 19, 2021).

National policy initiatives to build economic resilience

In search of common cross-country policy initiatives that both enhance African resilience to shocks and take account of variable financial and institutional capacity to implement them, the following themes are indicated as an agenda for using the COVID recovery to advance longerterm, restructuring objectives of an inclusive and just climate transition.

Food and social security grants

South Africa has the capacity to consider extending a food security grant to the remaining adult population that lives in poverty regardless of employment status. Any extension of food packages, institutional feeding schemes, social grants or small farmer agricultural input subsidies can be considered a more inclusive means of fostering fiscal trickle-down to the most vulnerable (disproportionately women) across all the countries in the case study cohort. Effectiveness must be measured against alleviating food stress or crisis, and malnutrition. Revenue measures that can alleviate food stress include duty and VAT exemptions on basic foodstuffs.

Climate and development finance

In accordance with the Paris Agreement on setting national targets for carbon emission reductions (Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs), individual countries are expected to align their infrastructure and industrial development plans to the green agenda of decarbonising energy and fuel supplies and recycling waste. South Africa’s dominant formal economy is nearly 80% dependent on coal resources. Decommissioning the coal industry and recommissioning the associated petrochemical complex will generate localised job losses and require major reskilling for a just transition. Similar challenges apply to Nigeria’s continued oil dependency, while all the other high-growth case study economies still have carbon fuel extraction projects in the pipeline. These adaptation challenges require a funding stream equivalent to those being established for mitigation through alternative energy production, grid extension, transport and industrial reengineering.

Industrial and trade policy

African countries began trading under the AfCFTA in 2021. The AfCFTA’s longer-term objectives are to remove intra-African tariff barriers and apply a common external tariff to the rest of the world. It is also aimed at developing common standards for technical barriers to trade (rules of origin, sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards, licensing requirements, local content and ownership) and other non-tariff barriers (surtaxes, quotas, production subsidies and monopolistic/monopsonistic distributors). These will be built on, and provide an alternative to, existing regional economic community arrangements, and will be negotiated on a product-byproduct basis over the medium term and beyond. A dispute resolution mechanism serves to develop the institutional architecture on a case-by-case basis.17Trade Law Centre, “AfCFTA Legal Texts and Policy Documents”, https://www.tralac.org/resources/by-region/cfta.html

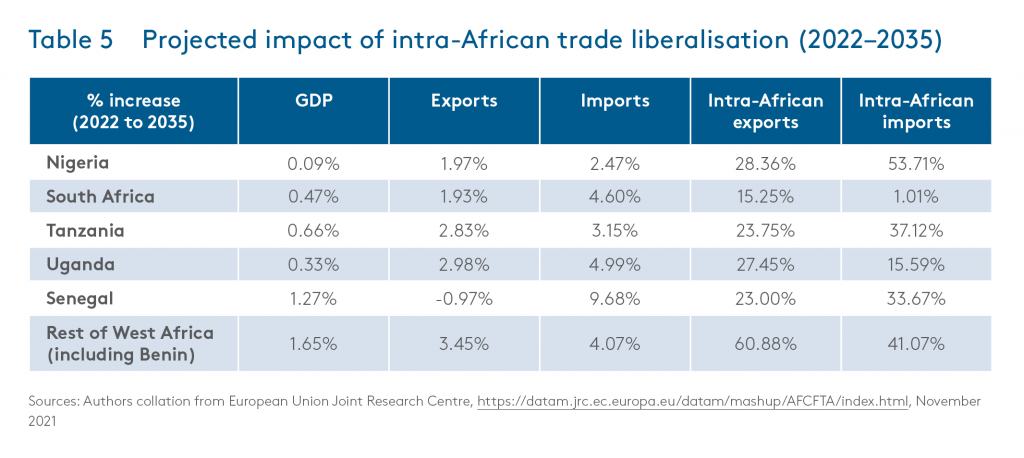

The associated aim is to promote intra-African export orientation in agricultural and industrial development, and to develop regional value chains connected to global ones. Table 5 indicates the modelled impact of the AfCFTA tariff reduction schedule and a removal of non-tariff barriers to 2035 on intra-African trade, international trade and GDP. The results presented are an average of four possible strategies guiding the choice of sensitive and excluded products, and the speed of liberalisation, namely tariff maximisation, food security enhancement, promotion of industrialisation and utilisation of comparative advantage.

Diversifying revenue sources

Many African governments are over-reliant on natural resource and international trade taxes. This locks in carbon fuel dependency and domestic protection, where the future challenges are to decarbonise and dismantle barriers to trade (or at least level the playing fields). The easiest replacement is higher domestic sales taxes. Flat rate sales taxes are income-regressive in that poorer consumers spend greater proportions of their earnings than richer ones. Exemptions or lower rates on food and medical items can ameliorate the distributional effects but may be administratively costly. Higher income, property and wealth taxes are the most incomeprogressive if they are graduated by income level. Corporate profit taxes are considered the least market-distorting form of redistributive taxation.18Nikolay Gueorgueiv and Ryota Nakatani, “Sharing the Gains of Automation: The Role of Fiscal Policy”, IMF Blog, November 18, 2021. It is not clear whether the recent G20 agreement on a minimum global corporate tax of 15% and base erosion and profit sharing will benefit African governments, where corporate income tax rates are generally higher than 15%, and complex intermediation between African regional and global supply chains is often designed with exploiting intra-African tax avoidance loopholes in mind.19Ian Steel, “What Does the Global Tax Deal Mean for Lower-Income Countries?” (Presentation, Overseas Development Institute, London, July 7, 2021). Carbon taxes are the most effective fiscal means of disincentivising carbon fuel usage.

Global policy initiatives

This final section addresses some of the global policy initiatives that African countries can collectively negotiate with and over to improve their resilience to shocks by accessing a more equitable share of global development finance flows, based on (greater) need and (lower) contribution to the climate crisis.

Concessional debt

In August 2021 the IMF issued $650 billion worth of SDRs, thereby increasing their share of global reserve assets from 2% to 7%. These are allocated to countries primarily according to their share of world GDP, but also their openness, diversification and reserve holdings. SSA countries collectively receive 3.6% of the allocation. Since they are intended to restore national reserve adequacies, and since African low- and middle-income countries are most at risk (rather than the advanced economies, which receive over 60% of the allocation), the IMF has asked that the richer countries voluntarily donate SDR allocations to the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) for on-lending to low- and lower-middle-income countries. Thus far, a further 3.6% has been redirected to the PRGT.20IMF, “Special Drawing Rights”, Factsheet, August 5, 2021.

Proposals have been put forward to redirect $50–100 billion into a Resilience and Sustainability Trust to support climate-vulnerable low- and middle-income countries with loans conditional on policies consistent with country NDCs. The eligibility criteria for climate vulnerability favours Vulnerable 20 (V20) members and is thereby skewed towards smaller economies (with burdens affordable to advanced economies).21Paul Steele, Sejal Patel and Ulrich Volz, Creating a Resilience and Sustainability Trust at the IMF: How to Support Climate-Vulnerable Countries, Report (London: International Institute for Environment and Development and SOAS University of London, October 2021). Established in 2015, the V20 is a group of finance ministers of small and medium-size economies that are deemed especially vulnerable to climate crises. Five African countries, including Tanzania, are members of the V20. Of our case study countries, only Senegal and Benin would be eligible.

Climate and development finance

Standard and Poor’s estimates that current SDR allocations would restore reserve adequacy in only five of 44 eligible emerging economies. To restore adequacy for all eligible countries would require high-income countries to redirect 42% of their allocations.22Standard and Poor’s Global, “An SDR Is Born: The IMF Creates a Reserve Asset for Low-Income Countries”, June 22, 2021. The start of an African negotiating stance is indicated in the Declaration from the Summit on Financing of African Economies of May 2021. The declaration proposes that advanced countries redirect 55% of their SDR allocations, half to low-income and half to middle-income African countries (including, therefore, all our case study countries). The excess – over-restoring central bank reserve adequacy – should be directed via the existing development finance networks (the World Bank, the African Development Bank [AfDB] and other regional development finance institutions), in support of the Alliance for Entrepreneurship in Africa to establish equity and venture capital facilities, and to micro-finance institutions. The uses of these funds should be devoted two-thirds to expanding green energy infrastructure and the remainder to digitisation. Important catalytic innovations include policy and project guarantees, project bankruptcy procedures and political risk insurance.23The declaration was signed by all G7 countries, China and most major African nations (with the exception of Uganda among our case study countries).

The climate finance component of this proposal can be seen as part of the effort to accelerate progress towards achieving the $100 billion annual commitments made to redirect bilateral, multilateral and mobilised private finance into concessional loans, grants, guarantees and equity to mitigate climate change. As of 2019, $79.6 billion had been raised (36% from bilateral, 43% from multilateral and the rest from private sources) and instrumentalised as 71% loans and 27% grants.24Elena Ares and Philip Loft, “COP26: Delivering on $100 Billion Climate Finance” (Insight, UK Parliament, House of Commons Library, London, November 6, 2021).

Debt restructuring

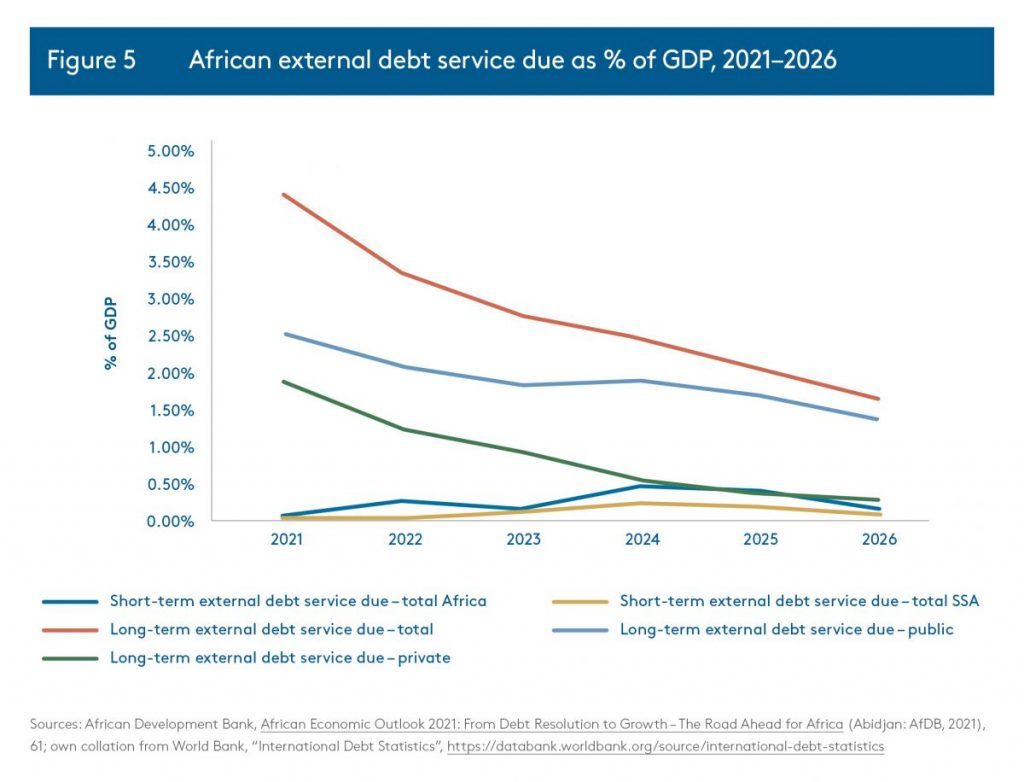

Figure 5 illustrates projected debt service-to-GDP ratios for SSA to 2026. In respect of long-term external debt, the World Bank expects the relative burden to decline owing to a combination of a return to structural (high growth) trends, reduced take-up of new commitments and declining interest rates through monetary accommodation. This is true for both public sector and publicly guaranteed private debt, at average interest rate of 1.56% and maturity of 27.8 years in 2020, but especially private non-guaranteed, at interest rates of 3.89% and maturity of 13.3 years. Where official multilateral and bilateral lenders are more amenable to debt restructuring, the IMF can only exhort the private sector to offer rates and maturities at similar terms. In late 2021 there were signs of slower recovery and monetary tightening, which may induce less optimistic projections.

Given the assessed vulnerability of African governments to debt distress, even slight monetary tightening can tip the balance. Of particular concern to the AfDB is an expected sharp increase in short-term external debt service due. Depending on source and jurisdiction, this burden is likely to increase between five- and seven-fold by 2024 before softening to more manageable levels. While the AfDB expected termination of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) by the end of 2021, the World Bank appears more sanguine about an extension of this commitment to bilateral loan repayment deferrals to the end of 2022. Thereafter, multilateral IMF concessional debt incurred during 2020, a surge of decadal Eurobond issues from the 2010s, and shorter-term Chinese and Arab lending come to maturation.

The T20’s Task Force on International Finance proposed a World Recovery Fund, which would enable lower- and middle-income countries to swap expensive, short-term debt with cheaper, long-term debt guaranteed by richer country governments with better credit ratings. Collateral would be project-based and include any financial or physical asset. Conditionalities for climate risk mitigation and adaptation would be adopted.25Alicia García-Herrero, “A World Recovery Fund to Overcome Developing Countries’ Post-COVID Debt Woes” (Policy Brief, T20 Task Force 9 International Finance, September 2021). In respect of legacy debt swaps (suitable for recommissioning), previous debt relief episodes suggest that creditors can expect up to a 30% haircut.

Aid and food security

The Declaration of the Summit on Financing of African Economies proposed that the advanced national economies commit 0.2% of their GDP annually to ODA for a variety of purposes and objectives. Between 2019 and 2020, the proportion of Africa’s population under food stress rose from 10.2% to 13.3%, dropping to 12% in 2021, while those in a state of food crisis, emergency or catastrophe rose from 5.4% to 7.3%.26Food Security Information Network, 2021 Global Report on Food Crises (Rome: World Food Programme, May 5, 2021). Where infrastructure and digitisation can be debt or equity financed, and security services the cause of food insecurity, the most effective target of ODA spending would be on extending national and continental food security systems (as outlined earlier).

Conclusions and recommendations

The concluding section makes some tentative policy recommendations for African governments endeavouring to align their domestic socio-economic developmental objectives to build future resilience to external shocks with South–South international dialogues and North–South negotiations for a just climate transition. The focus is on the intersect between financial capacity, inclusivity and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Where the poorer, secondary economic nodes (Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda) used their accumulating pre-COVID debt to invest, generate growth and reduce poverty, primary nodes (such as South Africa and Nigeria) have been constrained by their legacy dependence on coal and oil technologies, respectively. Climate risk mitigation and adaptation will require further borrowing, which, in turn, helps deepen and diversify African financial markets.

Debt restructuring is an alternative to austerity, inflation or financial repression. The short- to medium-term constraints of rising short-term debt servicing can be alleviated by an extension and graduated withdrawal from the bilateral DSSI, a similar negotiation over multilateral debt relief secured during the COVID shock of 2020–21, and facilitation of private and domestic debt restructurings.

Other than exhorting creditor nations to act on their green finance pledges and donate their SDR allocations, African nations should push for IMF membership quotas to take account of population [potential and need] in addition to its [primary] criterion of GDP. They should also question sovereign credit rating methodologies, which give too little weight to the growthenhancing and poverty-reducing impacts of debt incurred.

Domestic tax revenue mobilisation and diversification are a concomitant requirement for simultaneously meeting debt service commitments, extending the food security net, enabling mass vaccination and concessionalising green infrastructure finance.

Volatile natural resource taxes, customs and excises should be turned into counter-cyclical stabilisers where excess funds are accumulated to fund loan guarantee reserves, and withdrawn in the event of project delay or failure. Inasmuch as the new global deal on corporate income taxes raises African country revenues from this source, the excess should be used to subsidise the renewable energy and circular economy transition.

Given the low proportion of the labour force in formal employment, personal income tax bases in Africa are generally small, and appropriately used to extend unemployment benefit coverage during recessions. The twin moral imperatives of extending food security and a mass vaccination programme are sufficient justification for increases in broad-based sales tax rates, suitably complemented with matching ODA grants. Income progressivity can be enhanced with exemptions or lower VAT rates on foodstuffs and medical supplies. Other government services – but prioritising education – will have to suffice with improved tax collection and spending efficiency in the medium term.

Watch a video summary

Acknowledgement

SAIIA, CSEA and our think tank partners acknowledge the support of the International Development Research Centre for this research paper and the CoMPRA project.

About CoMPRA

The COVID-19 Macroeconomic Policy Response in Africa (CoMPRA) project was developed following a call for rapid response policy research into the COVID-19 pandemic by the IDRC. The project’s overall goal is to inform macroeconomic policy development in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by low and middleincome countries (LMICs) and development partners that results in more inclusive, climate-resilient, effective and gender-responsive measures through evidence-based research. This will help to mitigate COVID-19’s social and economic impact, promote recovery from the pandemic in the short term and position LMICs in the longer term for a more climate-resilient, sustainable and stable future. The CoMPRA project will focus broadly on African countries and specifically on six countries (Benin, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa). SAIIA and CSEA, as the lead implementing partners for this project, also work with think tank partners in these countries.

Our Donor

This project is supported by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The IDRC is a Canadian federal Crown corporation. It is part of Canada’s foreign affairs and development efforts and invests in knowledge, innovation, and solutions to improve the lives of people in the developing world.