Recommendations:

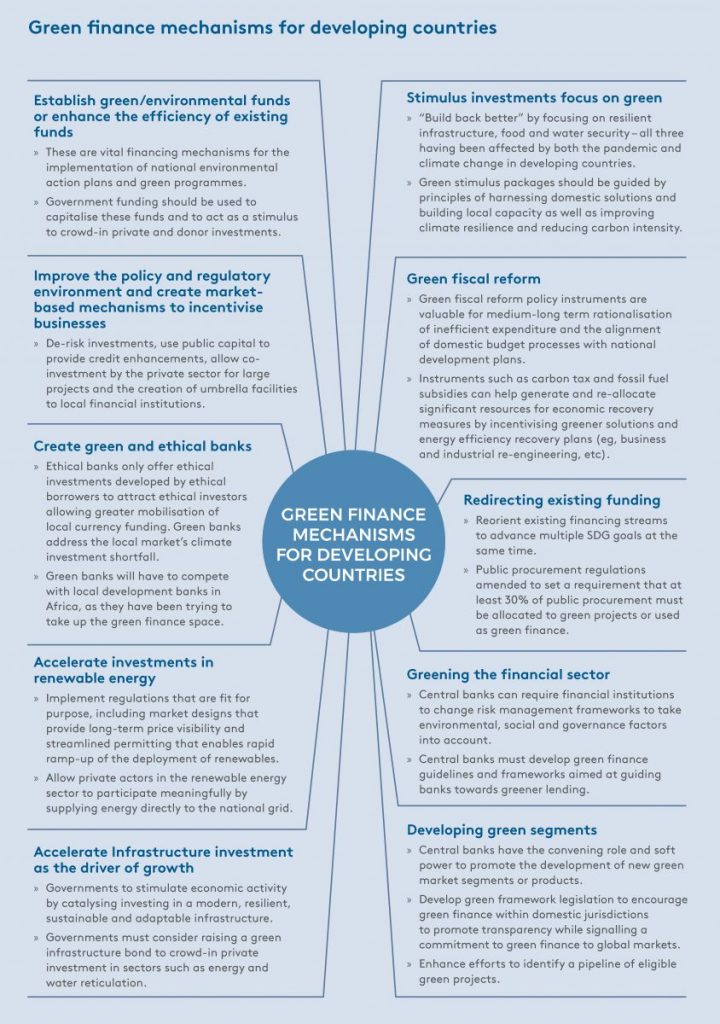

- African governments should enhance efforts to employ suitable green growth financing mechanisms (eg, accelerating investments in infrastructure and renewable energy, establishing or revamping green/environmental funds and other market-based mechanisms, ensuring stimulus investments focus on the Green Economy, implementing green fiscal reform, redirecting existing funding, greening the financial sector and developing green segments) that they deem appropriate to their domestic markets and developmental challenges.

- In particular, green bonds are one of the most readily accessible and economical options to help raise large amounts of capital for infrastructure development to meet environmental targets in Africa.

- To catalyse the transition to a Green Economy, targeted public finance is needed to decrease investment risk, create a stimulus for green investments and leverage private finance for green investments – especially now that private capital shows growing interest in supporting the achievement of SDGs.

Executive summary

To counter the devastating impact of COVID-19, calls are growing for countries to ‘build back better’ in an effort to create a more inclusive and sustainable economy that is climate resilient. Africa is facing glaring development and climate risk challenges, but the post-COVID-19 recovery plan offers it an opportunity to revitalise its economy using a green framework. In particular, green finance mechanisms can be employed for the continent’s green recovery. The objective of this policy briefing is to explore best practices in channelling investment towards a green economic recovery to promote inclusive and sustainable investment. Examples of such best practices include investment infrastructure and renewable energy, green/environmental funds and other market-based mechanisms, ensuring stimulus investments focus on green fiscal reform, redirecting existing funding, greening the financial sector and developing green segments.

Introduction

COVID-19 has had an unprecedented negative impact on African economies, heightening their vulnerability to the effects of climate change. Beyond the immediate health crisis, the pandemic has triggered an economic slowdown that has severely hampered Africa’s development ambitions, curtailing two decades of macroeconomic improvements and socio-economic gains. The dramatic decline in industrial production, energy demand and transport activity (which in turn has led to lower levels of pollution) has prompted debates about long-term shifts in consumer and industrial behaviour. Such shifts could reorient economic policy towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) despite rising debt levels and falling export revenues, which will make financing green investments a challenge for African countries.1Godwell Nhamo, “Green Economy Readiness in South Africa: A Focus on the National Sphere of Government”, International Journal of African Renaissance Studies 8, no. 1 (2013): 115–142, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263339273.Finance is one of the pillars of Green Economy readiness in Africa. In particular, political will is a critical success factor in unlocking green finance, which encompasses financial policies, programmes, products and services that support the transformation of an economy, as well as its systems and institutions, to attain sustainable development.2Zanizeni Sustainable Finance, “Green Finance Concept Document to Inform the 2019 Partnership for Action on the Green Economy (PAGE) Conference” (Working Paper, Department of Environmental Affairs, Pretoria, January 10–11, 2019), https://www.tips.org.za/images/Green_Finance_Concept_Document.pdf.

Africa is now facing at least $500 billion in economic costs (2020) owing to the coronavirus.3Kingsley Ighobor, “AU Study: COVID-19 Could Cost Africa $500 Billion, Damage Tourism and Aviation Sectors”, African Renewal, April 15, 2020, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/au-study-covid-19-could-cost-africa-500-billion-damage-tourism-and-aviation-sectors.Seven of the world’s 10 most climate-vulnerable nations are in Africa.4Alnoor Amlani, “Africa Shapes Its Own Green Financing Destiny”, ACCA Global, April 1, 2019, https://www.accaglobal.com/my/en/member/member/accounting-business/2019/04/in-focus/green-financing.html.In 2020 alone the continent’s interest repayments on its debt amount to $400 billion, indicating that it lacks the financial capacity to mobilise green stimulus packages and as such needs help.5Carlos Lopes, “How a Covid-19 Recovery Could Lead to a More Resilient Africa”, The Telegraph, May 20, 2020, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/how-to-be-green/covid-19-climate-smart-growth-africa/.Many African countries rely heavily on foreign income and earnings from exports and tourism markets, which have been severely damaged by the pandemic.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that Africa’s financial requirements to adapt to climate change range from $20–$30 billion per year until 2030, but they can be met through diversification of both finance mechanisms and funding sources.6Mindy Hauman and Tallat Hussain, “Green Finance in Africa”, White & Case LLP, February 7, 2018, https://www.whitecase.com/publications/insight/green-finance-africa.The continent is facing a twin COVID–climate crisis. If it can successfully ‘build back better’7Global Centre on Adaptation, “Is a Green Recovery in Africa Possible after Covid-19?” (Policy Brief, GCA, Rotterdam, May 22, 2020), https://cdn.gca.org/assets/2020-05/GCA-AAI_Policy_Brief.pdf.as it recovers, it will achieve a triple dividend by reducing pandemic risks while increasing climate resilience and strengthening economic recovery.

The relevance of green finance has grown in the last few years, but COVID-19 has made it even more prominent as a central theme underpinning new sustainable economic recovery strategies and policies in the wake of the pandemic. It is against this backdrop that this policy briefing explores various green growth financing mechanisms that can be used for Africa’s green recovery. It also focuses on green/environmental funds and other market-based mechanisms such as green and ethical banks. The policy briefing then looks at renewable energy and infrastructure investment. This is followed by an exploration of green stimulus investment packages, green fiscal reform, greening the financial sector and the development of sustainability segments.

Green/environmental funds and other market-based mechanisms

Climate finance has become important in addressing both climate change and sustainable development objectives. This has led to a broadening of the scope and mandate of environmental funds (EFs), which are vital financing mechanisms for the implementation of national environmental action plans and green programmes. Some of the key success factors of EFs include:

- a strong government commitment to ensuring that they are used only to provide funding and technical expertise, build capacity and support the transition to a Green Economy;

- a strong governance system with representation from diverse sectors;

- long-term financial commitment; and

- strong legal and financial practices.

Adding stakeholders from the private sector and non-governmental organisations will ensure greater transparency in the governance and management of EFs. Government funding should be used to capitalise EFs and to act as a stimulus to crowd-in private and donor investments. EFs should, however, aim to have diverse revenue streams in the medium to long term. Having clear priorities will also help attract grant funding. It is important that proper due diligence processes be followed to ascertain the bankability, scalability, additionality, replicability and sustainability of the project. This will help to identify the key sectors driving the Green Economy transition in a country while highlighting sectors that may need additional support. EFs should also consider funding innovative and strategic capacity-building programmes to support and strengthen domestic capabilities (infrastructure, resources and products, skills, etc.) in pursuit of a transition to a Green Economy.8Mohamed et al., “The Green Fund of South Africa”.Any economic support by the government, private sector or donor community should be consistent with resilient and climate-smart growth in order to ensure that the investments made now have long-lasting impacts.

In order to attract private sector investment in climate-resilience programmes, governments must improve the policy and regulatory environment and create market-based mechanisms to incentivise businesses. For any market strategy to be successful in unlocking green finance, it should focus on creating a dedicated green fund, de-risking investments and credit enhancement, and co-investing with local financial institutions. De-risking can be done by providing long-term grant and concessionary funding to an investment. Public capital can be used to provide credit enhancements (by government-owned development finance institutions [DFIs]) that will attract private capital to sustainable green investments and serve to partially de-risk investments for the private sector, allowing the investment to meet the required rate of return. Market practice strategies to unlock green finance should also include co-investment by the private sector for large projects and the creation of umbrella facilities to local financial institutions. DFIs or green banks can advance the minimum financing required to make the investment viable, with the remainder of the financing requirement topped up with private capital. This way, public funds are used to leverage private sector funding. In instances of lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with good investment opportunities but high transaction costs per dollar invested owing to their small size, international funders can provide a large umbrella facility to a local financial institution with low transaction costs to on-lend those funds to smaller entities and projects.9Zanizeni Sustainable Finance, “Green Finance Concept Document”.

African countries are starting to experiment with innovative financing approaches such as ‘green market-ready products’, a green growth fund that will be replenished through proceeds from trading credits from emission reduction projects, crowd-funding for clean energy and green bond financing, etc, to finance adaptation and sustainable development projects. The creation of green and ethical banks has been an interesting development in sustainable finance. Ethical banks are financial institutions that invest ethically and sustainably. These banks only offer ethical investments developed by ethical borrowers to attract ethical investors, which may allow greater mobilisation of local currency funding for sustainable investments. Green banks are defined as public-purpose finance institutions dedicated to green investment with the aim of addressing the local market’s climate investment shortfall. Green banks will have to compete with local development banks in Africa, as they have been trying to take up the green finance space. Be that as it may, the keen exploration of green banks in Africa (in Morocco, South Africa and Malaysia), together with profitability, sustainability and deposits, shows that there may be gaps in the provision of finance that existing institutions are not able to fill.10Zanizeni Sustainable Finance, “Green Finance Concept Document”.For instance, Mozambique is a climate-vulnerable state that has recently experienced (October 2020) extreme flooding, prompting the government to launch a Green Economy Action Plan solidifying commitments towards sustainable infrastructure, among others. Mozambique will need to build investor confidence after its sovereign default in January 2017, but the currency (the metical) rose by 19% (against the dollar) last year, making foreign debts easier to service.11Hauman and Hussain, “Green Finance in Africa”.South Africa’s National Strategy for Sustainable Development and Action Plan is a policy framework that sets out steps to a just transition to a Green Economy. It also laid the foundation for establishing its Green Fund in 2012. The fund is part of a national environmental programme managed and implemented by the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) on behalf of the Department of Environmental Affairs. One of its mandates is to leverage and attract additional resources to support South Africa’s transition to a Green Economy by using public finance as a stimulus for green investments.12DEA, “The Green Fund”, https://www.sagreenfund.org.za/wordpress/.Other African countries with EFs include Namibia and Mauritius.

Renewable energy

According to Stanford University, the world could save ZAR13Currency code for the South African rand.200 trillion ($12.2 trillion) on fuel costs and a further ZAR 180 trillion ($11 trillion) per year by reducing the health and ecological effects of fossil fuel pollution if it managed to achieve a 100% renewable energy system. This is because renewable energy is becoming increasingly cheaper than fossil fuels.14Dharna Noor, “Could We Have a Global Green New Deal?”, Gizmodo, December 20, 2020, https://earther.gizmodo.com/could-we-have-a-globalgreen-new-deal-1840535860.The difference between the 2008 global financial crisis and the current COVID-19 crisis is that the cost of renewable energy generation is now competitive with that of fossil fuels.15Oxford Business Group, “Can Emerging Economies Afford a ‘Green’ Recovery from Covid-19?”, April 28, 2020, https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/can-emerging-economies-afford-green-recovery-covid-19.As such, a green recovery plan in Africa should consider renewable energy as one of the main components of economic stimulus packages post-COVID-19. Renewables offer a way to align short-term policy action with medium- and long-term energy and climate goals, and as such must be the backbone of national efforts to restart economies in the wake of the pandemic. Policy reforms to enable a decrease in renewable power costs can shift markets and contribute to a green recovery. As lockdowns are eased, energy demand will increase as additional energy capacity is required, giving countries an opportunity to provide clean and affordable power and the energy security needed for a sustainable economic recovery. Governments can use this opportunity to stimulate demand by electrifying their economy with renewable energy. This could be a key building block in economic recovery as it can deliver new electricity infrastructure with private investments, and help the continent achieve sustainable economic recovery. Governments should proceed with speed to implement regulations that are fit for purpose, putting clean energy investments at the centre of economic recovery and economic stimulus packages, including market designs that provide long-term price visibility and streamlined permitting that enables rapid ramp-up of the deployment of renewables.16PowerinfoToday, “SAWEA Pushes for Green Recovery Plan in South Africa”, Press Release, https://www.powerinfotoday.com/renewable-energy/sawea-pushes-for-green-recovery-plan-in-south-africa/.For instance, the South African Wind Energy Association is of the view that a green recovery plan in South Africa can be achieved by removing regulatory barriers. This will enable the private sector to freely purchase renewable energy and promote 100% renewable energy demand by end-consumers in order to allow corporates to extend production to meet sustainability targets. In order for private capital to flow into renewable energy, African states must allow private actors in this sector to participate meaningfully by supplying energy directly to the national grid. Governments must deregulate to allow competition – competition does not necessarily mean privatising state-owned enterprises (SOEs); it means allowing other companies to operate in the same market as SOEs.

According to a report by the International Renewable Energy Agency, accelerating investment in renewable energy could underpin the global economy’s COVID-19 recovery by adding almost $100 trillion to gross domestic product by 2050. Increasing renewable energy investments would in the long term pay for itself by returning between $3 and $8 for every $1 invested, and quadrupling the number of jobs in the sector to 42 million over the next three decades.17Oxford Business Group, “Can Emerging Economies Afford”Low-carbon solutions are cheaper over their lifetimes and offer an investment opportunity, as 77% of the projected $13.3 trillion in new power generation investment by 2050 will go to renewable energy.18Bloomberg NEF, “New Energy Outlook: Investments”, 2019, https://bnef.turtl.co/story/neo2019/page/2/2?sf107867015=1.Studies have shown that if South Africa had a renewable energy system it could cut energy costs by a quarter, create 200 000 more jobs in the energy sector alone, lower the cost of energy by 25%, save 196 billion litres of water annually, make the energy system more reliable, and remove coal, which is the biggest source of air, water and climate pollution.19Alex Lenferna and Jennifer Wells, “To Recover from COVID-19, South Africa Needs Green New Deal”, Daily Maverick, April 24, 2020, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-04-24-to-recover-from-covid-19-sa-needs-green-new-deal/.Although infrastructure spending is a tool for stimulating economic growth after the pandemic, green energy projects should still be vetted carefully to ensure they are well planned, efficient and cost effective.

Infrastructure investment

With increased protectionism part of the post-COVID-19 future,20Antonio Ortiz-Mena, “COVID-19 and Protectionism: The Worst May Be Yet to Come”, Brinknews, July 23, 2020, https://www.brinknews.com/covid-19-protectionism-the-worst-may-be-yet-to-come-nationalism-trade-supply-chains/.some countries will pursue a strategy that places the state at the centre of their economic recovery, as infrastructure will be the driver of growth. Africa has persistently under-spent on infrastructure. In order to bring real growth, its infrastructure requirements are $130–170 billion per year.21African Development Bank, African Economic Outlook 2018 (Abidjan: AfDB, 2018), https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/African_Economic_Outlook_2018_-_EN.pdf.Aggregate demand is expected to remain depressed for some time, leaving governments to enact further policy measures to stimulate economic activity through spending. They can be made 21st-centuryready by catalysing investing in a modern, zero-carbon infrastructure system and a green energy environment. This will be effective in addressing depressed demand by creating jobs while also laying the foundation for sustainable long-term growth. Although feasibility in developing countries could be a concern, countries could explore various avenues for funding green infrastructure. These include redirecting fossil fuel subsidies towards more productive and sustainable areas of the economy, and introducing energy or carbon taxes. Private equity could also be an effective alternative source of funding, as many funds are now assessing new strategies to allocate capital, including finding appeal in links to the SDGs.22Oxford Business Group, “Can Emerging Economies Afford”.

Investment in modern, resilient, sustainable and adaptable infrastructure is fundamental to sustain the continent’s growth and enable it to operate effectively in future. EU research suggests a $4 return on every $1 invested in infrastructure.23GCA, “Is a Green Recovery”.Central to the economic recovery strategies of African countries will be measures taken to stimulate supply and demand through substantial infrastructure build programmes. South Africa’s answer to reviving its economy – which is currently under severe financial constraint, as outlined in its June 2020 supplemental budget – is investing in infrastructure to support structural transformation, growth and job creation. Its sustainable Infrastructure Development Symposium has pulled in financial institutions such as the New Development Bank (NDB), the DBSA and the AfDB, which have all agreed to help.24Tshegofatso Mathe, “Jury’s Out on Green Recovery”, Mail & Guardian, July 9, 2020, https://mg.co.za/business/2020-07-09-jurys-out-on-greenrecovery/.The plan is to galvanise ZAR 2.3 trillion ($141.1 billion) in new infrastructure investment over the next decade, estimated to create more than 1.8 million jobs. The government is also considering raising a green infrastructure bond to crowd-in private investment in sectors such as energy and water reticulation.25Songo Didiza, “Breathing New Thinking into Social Upliftment Towards a Green Recovery Plan for South Africa”, GreenEconomy.Media, https://greeneconomy.media/breathing-new-thinking-into-social-upliftment-towards-a-green-recovery-plan-for-south-africa/.

Stimulus investments focus on green

Most African countries have managed to deploy fiscal stimulus packages, but they need to be re-focused on the twin COVID–climate crises in order to achieve a green recovery and come out of these crises more resilient. The Global Center on Adaptation and African Adaptation initiative have made recommendations on ensuring stimulus investment in Africa is used to ‘build back better’ by focusing on resilient infrastructure and food and water security – all three having been affected by both the pandemic and climate change. COVID-19 could create a severe food security crisis in Africa, where 400 million people live in poverty and 74% of the population is already food insecure. Sub-Saharan Africa relies on massive food imports for its fast-growing population, which is estimated to increase from $35 billion in 2017 to $110 billion by 2030. Over 320 million people in Africa do not have access to safe drinking water, and over half the population does not have access to sanitation.26GCA and African Adaptation Initiative, “Integrated Responses to Building Climate And Pandemic Resilience in Africa” (Policy Brief, GCA and African Adaptation Initiative, Rotterdam, May 2020), https://www.africaadaptationinitiative.org/assets/AAI-GCA%20Policy%20Brief.pdf.It is therefore imperative to use stimulus packages to enhance access to water and sanitation. This should happen in parallel to improving water governance by promoting investments that take into account the management of ‘natural infrastructure’ and support the effective distribution of scarce water resources for multiple uses.

A green stimulus should be at the core of Africa’s recovery effort. Such a plan should be tailored to domestic socio-economic conditions instead of transplanting green stimulus models from developed countries. Green stimulus packages should also be guided by the principles of harnessing domestic solutions and building local capacity, as well as improving climate resilience and reducing carbon intensity and resource inefficiencies in African countries. These packages should be broadened beyond renewable energy to include water and other ecological infrastructure.27Terence Creamer, “Placing Green Stimulus at Heart of South Africa’s Post Pandemic Recovery Would Yield Big Co-Benefits”, Polity, June 4, 2020, https://www.polity.org.za/article/placing-green-stimulus-at-heart-of-south-africas-postpandemic-recovery-would-yield-big-co-benefits-2020-06-04.Five key pillars for green recovery packages28Creamer, “Placing Green Stimulus at Heart”.can be adopted by African countries:

- Build the network infrastructure needed for a green and just transition, such as smart electricity and water grids, e-mobility and broadband infrastructure and improved rail and waste management; and maintain ecological infrastructure.

- Make the regulatory changes to unlock private sector investment in sustainable energy, water, waste and sanitation systems. For instance, governments have rolled out emergency water and sanitation provisions to un/under-serviced informal communities as they are considered hotspots for the spread of COVID-19. However, these provisions are done in a temporary manner, making them expensive. GreenCape’s Market Intelligence Report 2020 shows that investment opportunities in infrastructure in agro-processing and water and sanitation could be significant; for example, non-sewage sanitation for informal settlements and schools in communities that do not have access to sewage infrastructure.

Green fiscal reform

Green fiscal reform is the umbrella term for the application of pricing mechanisms that internalise externalities and mobilise public revenues. Thus, Environmental Fiscal Reform (EFR) uses a number of tax and pricing instruments that can raise revenues while furthering environmental goals such as mitigating climate change. There is a range of EFR instruments, but their suitability differs by country and sector. In particular, environmental taxes are used to deal with negative externalities. Cap-and-Trade systems are ‘internalising’ mechanisms for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that set maximum levels of emissions and provide incentives to remain below those levels through a trading system. Investment incentives that are used include low-interest loans, tax exemptions and micro finance. Other incentives that offer direct support are subsidies and feed-in tariffs.29Zanizeni Sustainable Finance, “Green Finance Concept Document”Green fiscal policy instruments such as carbon tax and fossil fuel subsidies can help generate and re-allocate significant resources for economic recovery measures by incentivising greener solutions and energy efficiency recovery plans (eg, business and industrial re-engineering, etc).30Gilbert E Metcalf, “A Conceptual Framework for Measuring the Effectiveness of Green Fiscal Reforms” (Paper, Green Growth Knowledge Platform Third Annual Conference, University of Venice, Venice, January 29–30, 2015), https://greengrowthknowledge.org/sites/default/files/Metcalf_A_Conceptual_Framework_for_Measuring_the_Effectiveness_of_Green_Fiscal.pdf.For instance, South Africa, which also has a carbon tax, provided subsidies for the roll-out of one million solar water heaters in an effort to reduce GHG emissions from the use of coal-powered electricity.31Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, “Solar Water Heating”, http://www.energy.gov.za/files/swh_frame.htmlOn the other hand, the removal of harmful subsidies or feed-in tariffs is also a financing mechanism employed to achieve certain SDGs.32Zanizeni Sustainable Finance, “Green Finance Concept Document”.One example is Egypt’s halving of the fiscal cost of subsidies to bring average electricity tariffs closer to cost recovery, using the World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Program.33World Bank, “Reforming Fossil Fuel Subsides for a Cleaner Future”, November 21, 2017, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/11/21/reforming-fossil-fuel-subsidies-for-a-cleaner-future.

Green fiscal reforms, if designed well, can be a valuable instrument for medium- to long-term rationalisation of inefficient expenditures, such as environmentally harmful subsidies, and the alignment of domestic budget processes with national development plans aimed at achieving sustainable and inclusive growth. Green fiscal reform has not taken off owing to obstacles such as special interest groupings’ lobbying against it; lack of political will; limited transparency and awareness; and administrative, institutional and technological constraints.34Sirini Withana, “Overcoming Obstacles to Green Fiscal Reform”, The International Journal on Green Growth and Development 2, no. 2 (2016): 161–188, http://bookstore.teri.res.in/docs/journals/IJGGD_Vol%202%20Issue2_Article_4.pdf.It is, however, important to assess the efficiency and distributional implications of any proposed environmental fiscal reforms.

Redirecting existing funding

Sustainable finance is more than just increasing investments through new funding streams – it is also about finding ways to reorient existing financing streams to advance multiple SDG goals at the same time. Public procurement can be used as a lever to achieve development impact. For example, public sector regulations can be amended to set a requirement that at least 30% of public procurement must be allocated to green projects or used as green finance. The European Investment Bank and the African Export-Import Bank have made $355 million available to ensure that African businesses have the working capital to sustain jobs and maintain vital imports. A quarter of these funds is earmarked for climate change mitigation and adaption to help the continent maximise opportunities for a green recovery. Support for green projects such as renewable power, energy efficiency and climate change adaptation measures to reduce emissions and reduce energy use will help propel Africa towards a sustainable economic growth path. A total of $234.3 million of these funds was previously allocated to trade-related investment – now it is redirected to those sectors most impacted by the pandemic.35“Sparking a Green Recovery to Keep Africa’s Economy Going”, ESI Africa, August 7, 2020, https://www.esi-africa.com/industry-sectors/renewableenergy/sparking-a-green-recovery-to-keep-africas-economy-going/.

There should be a review and update of existing government expenditure plans with the aim of adding energy and public transport projects, since they take a long time to prepare. Also, national budgets can be reallocated with the view of putting national climate/green/ environmental funds at the centre of economic recovery plans.

Greening the financial sector

Following a lack of clarity about which activities and assets can be defined as green, which was a barrier to scaling up green finance, the World Bank published guidelines for developing a green taxonomy. This will help to scale up green finance and assist regulators in emerging economies to ‘green’ their domestic financial systems. A ‘green taxonomy’ is a common language on environmental issues for use by the financial sector. It identifies activities or investments that deliver on environmental objectives, thereby helping the financial sector to efficiently channel capital towards environmentally sustainable projects by originating and structuring green banking products such as loans, credits and guarantees.36“World Bank’s Guide to Scale Up Green Finance in Emerging Markets”, ESI Africa, July 14, 2020, https://www.esi-africa.com/industry-sectors/financeand-policy/world-banks-guide-to-scale-up-green-finance-in-emerging-markets/.In such a market, investors seeking impact investment opportunities can easily identify those opportunities that comply with sustainability criteria. The methodology and recommended approach avoids one-size-fits-all definitions and standards by developing a taxonomy based on a country’s particular environmental objectives.

Central banks play a key role in facilitating the development of green finance in their domestic markets. They are urged to intervene as regulators to unlock green and sustainable finance by reducing information asymmetries and requiring financial institutions to change risk management frameworks to take environmental, social and governance factors into account. Central bank regulatory intervention can also ensure that financial institutions provide a technically sound justification for those activities and investments considered green. This is because environmental risks are not taken into account in Basel III, which provides the main regulatory guidelines for the global banking system. A voluntary approach is recommended for countries that have not started integrating green finance considerations into central bank regulations.37Zanizeni Sustainable Finance, “Green Finance Concept Document”.An example of central bank intervention in South Africa is the case of the Land Bank. It owns 29% of the country’s agricultural debt, and recently defaulted on two of its domestic medium-term notes (ZAR 50 billion [$2.63 billion]) owing to liquidity shortfalls. This led to Moody’s downgrading the bank further into junk status to B1, despite its having crossdefault clauses. The South African Reserve Bank responded by suspending (on 12 May 2020) the qualification of the Land Bank’s short-term debt (which was previously considered ‘High Quality Liquid Assets’) as collateral to obtain funding for liquidity from its repo auctions. Effectively, local banks were prevented from using the Land Bank’s debt for their Liquidity Coverage Ratio calculations.38“South Africa Strips Land Bank Debt of High-Quality Asset Status”, Reuters, May 12, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/safrica-landbank-idUSL8N2CU3W4.Climate risk poses a serious risk to the agricultural sector, and its effects are impacting the quality of the bank’s loan book, with some farmers struggling to repay loans. Half of the bank’s debt matures in 2021. The government has had to guarantee the Land Bank’s debt and adjusted bank capitalisation funding during the COVID-19 crisis.39Planet Tracker, “South Africa: A Call for Green Recovery”, May 14, 2020, https://planet-tracker.org/south-africa-a-call-for-green-recovery/.

Central banks have a role to play in ‘greening’ financial systems, especially in developing and emerging economies where environmental regulation is badly implemented by weak public institutions. In developing and emerging markets, central banks are powerful and sophisticated institutions overseeing the dominant banking sector within the financial system. If central banks were assigned an environmental mandate, they could effectively exert influence over private investment decisions through their command over the banking sector.40Ulrich Volz, “On the Role of Central Banks in Enhancing Green Finance Inquiry” (Inquiry Working Paper 17/01, UN Environment and Centre for International Governance Innovation, London, February 2017), https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/57004893/banks-in-enhancing-greenfinance.In addition, central banks’ financial market expertise and transnational networks through their various regional and continental initiatives can promote ‘best practice’ reforms in the financial sector. The UN Environment Programme41Volz, “On the Role of Central Banks”.recommends, with caution, potential tools that central banks can use to impact investment decisions, create and allocate credit into green investments, and direct credit away from environmentally harmful activities.

- Introduce green macroprudential regulation and climate-related stress testing to address environmental systemic risk. The former includes ceilings on credit extension to certain carbon-intensive or polluting activities and exemptions from credit ceilings that can be used to channel investments into priority sectors. Suggested macroprudential instruments include higher risk weights either for carbon-intensive and dependent sectors (such as transport, mining and energy) or for particularly carbon-intensive and dependent companies in these sectors. Climate-related stress testing would assess the likely impact of hypothetical climate scenarios on the financial health of individual financial institutions and the financial system as a whole with the aim of ascertaining their resilience to adverse shocks.

- Use directed green credit policy instruments such as differential rediscount rates to incentivise commercial banks to extend credit to green investments with rediscounted bills at lower loan rates. There will be some compensation (partially or fully) for lending at subsidised rates of interest when they rediscount priority loans at the central bank on concessional terms.

- Green differentiated reserve requirements allow central banks to lower required reserve rates on privileged green assets, thereby favouring green investments over traditional investments.

- Institute differentiated capital requirements for low-carbon activities or green projects as it is done for loans to SMEs under BASEL III.

- Accept carbon certificates for low-carbon projects as part of commercial banks’ legal reserves – this will will enhance their market and make them exchangeable for concessional loans, thereby reducing the capital costs of low-carbon projects.

- Encourage green quantitative easing, whereby asset purchases are directed toward green financial assets such as green bonds, and reserve management to allow central banks to manage their assets according to social impact investment standards. This would release an additional $24 trillion to the funds already pledged under the UN Principles on Responsible Investing.

- Develop green finance guidelines and frameworks aimed at guiding banks towards greener lending.

- The Financial Stability Board

Other initiatives that contribute to the greening of the financial sector include the Sustainable Banking Network, which was established in 2012 to encourage the development of national policies or road maps for sustainable banking. The Sustainable Insurance Forum brings together industry players to share learning and best practice on greening the insurance industry. African countries such as Kenya, Morocco and Nigeria are also developing sustainable banking standards, initiatives, policies or regulations. Voluntary approaches may be effective in encouraging riskbased environmental due diligence and incentives, while mandatory requirements may be necessary to mobilise funding into specific green investment areas.42UN Environment, Green Finance for Developing Countries: Needs, Concerns and Innovations (Nairobi: UN Environment, July 2016), http://unepinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Green_Finance_for_Developing_Countries.pdf.The Global Investors for Sustainable Development (GISD) Alliance, a grouping of 30 CEOs, asset managers, banks and bourses, has agreed to urge the global investment community to integrate the SDGs into their core business models, introduce long-term performance metrics, accelerate company disclosure and report on social and environmental issues. The GISD is also calling for a coordinated international approach to financial regulation and encouraging ratings agencies to incorporate sustainable development considerations into their decision-making.43UN, “SDGs: Joint Statement by Global Investors for Sustainable Development Alliance (GISD)”, https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/GISD-joint-statement.pdf.

Developing green segments

Green bond issuance and green infrastructure investment account for less than 1% of total bond issuance and total infrastructure investment in 2016, respectively.44UN Environment, Green Finance for Developing Countries.The global green bond market has risen from $155.5 billion worth of issues in 2017 to an estimated $250–$300 billion in 2018.45Amlani, “Africa Shapes Its Own”.Central banks have the convening role and soft power to promote the development of new green market segments or products. According to the Climate Bond Initiative, green bonds were created to fund projects that have positive environmental or climate benefits. Issuing green bonds can become an important financial mechanism to support a green economic recovery, because they are aligned with the objective of curbing the climate crisis and can further boost struggling domestic economies in Africa through investments in the renewable energy market. Green bonds have considerable potential for growth, with investors keen on containing global warming, but they may shy away from markets with negative credit ratings. Green bonds tend to be oversubscribed and have advantages such as tax exemptions, making them a good option for countries that have had to approach financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund for funding to mitigate the effects of COVID-19.

It is important for first-time African sovereign, sub- and quasi-sovereign green bond issuers to develop green framework legislation to encourage green finance within their jurisdictions. This will also promote transparency while signalling a commitment to green finance of global markets. In light of the COVID-19 crisis, efforts to develop green bond frameworks and identify a pipeline of eligible green projects should be enhanced. Sub- and quasi-sovereign issuers are diverse in terms of geography and project type, demonstrating the flexibility of green bonds and their ability to be tailored to local circumstances. Encouraging green finance in African markers also requires governments to make public policy shifts in favour of greener and more climate-resilient economies while creating fiscal policies that make holding green assets more attractive.46Hauman and Hussain, “Green Finance in Africa”.

The GISD is working on defining sustainable development investing and developing a global voice to encourage the international investment community to actively invest in vehicles like COVID-19 bonds and the SDG500 fund, as well as renewable energy projects in the Middle East and a waste-to-energy project in India.47Leila Fourie, “Covid-19 Offers Chance to Build Back Better than Before”, Business Day, June 26, 2020, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2020-06-26-leila-fourie-covid-19-offers-chance-to-build-back-better-than-before/.This coincides with reports that sustainable funds attracted record inflows in Q1 2020 amid the COVID-19-induced financial crisis – a strong signal by investors that their interest in sustainable investments is growing.48Paul Chesser, “Study Debunks BlackRock Claims that ESG Funds Did Better During COVID”, National Legal and Policy Center, August 26, 2020, https://nlpc.org/2020/08/26/study-debunks-blackrock-claims-that-esg-funds-did-better-during-covid/.There is currently limited fiscal space for African governments to fund a green recovery, making the attraction of private capital essential and international capital through green bonds invaluable.49Hauman and Hussain, “Green Finance in Africa”.As African financial institutions are becoming more active in facilitating green finance, the AfDB issued its seventh green bond in 2018 after publishing a green bonds framework as early as 2013.50Amlani, “Africa Shapes Its Own”.The AfDB also mobilised around $12 billion between 2011 and 2015 for climate-resilient projects as part of its Climate Change Action Plan. It has also established the Africa Climate Change Fund aimed at providing funding for African countries to scale up green finance. In addition, African countries have access to the $2 billion Green Cornerstone Bond Fund (jointly provided by the International Finance Corporation and Amundi), designed to buy green bonds issued by emerging market banks that would not otherwise attract institutional investors owing to their risk–return profiles.51Hauman and Hussain, “Green Finance in Africa”

Hauman and Hussain52Hauman and Hussain, “Green Finance in Africa”have looked at developments that make the continent a prime candidate for funding through sovereign green bonds.

- As the largest producer of hydropower in Africa, Ethiopia hopes to increase its current output five-fold by 2030. To reduce reliance on hydropower, it is developing power stations and grids based on other renewable energies. These developments are prime candidates for funding through sovereign green bonds.

- As Nigeria prepares to transition to a sustainable future it can unlock the success of green bonds and enhance investor confidence by complying with its green bond framework together with the Nigerian Securities and Exchange Commission’s new listing rules, which codify the criteria and approval process of green bonds in the country. For a project to qualify as green, the investment must fall into one of eight listed categories similar to the categories of the Green Bond Principles. The latter’s requirements include a green use-of-proceeds commitment; a process for evaluating and selecting projects; and reporting. Nigeria’s debut sovereign green bond came to market in December 2017 and was the first sovereign green bond to gain the coveted certification of the Climate Bonds Initiative, setting a strong precedent for other African states to follow.

- Angola must invest in other sectors to reduce exposure to fluctuating oil prices. With many rivers, it could meet its ambitious hydroelectric energy generation target of 9 000 MW by 2025.

- Gabon, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of Congo were hit hard by falling oil prices in 2016 and, in an attempt to diversify their economies, their focus has shifted to forestry, agricultural and mining industries.

- Among those spearheading the development of a green bond market in Africa and the regulatory infrastructure to support it, the Moroccan Capital Market Authority (AMMC) has published a green bond framework and practical guidelines for green bond issuance. The Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy (Masen) issued Morocco’s first green bond to finance the country’s development of solar power projects.

- Kenya cross-listed its first green bond at the London Stock Exchange in January 2020 and the country is set to focus on creating an investment environment for sustainable finance through the development of a green bond framework and segment at the Nairobi Stock Exchange.

Conclusion

Emerging and developing countries are the least prepared to recover from the twin COVID– climate crises. A return to business-as-usual after the pandemic is not possible and innovative ways of reshaping Africa’s recovery and long-term sustainable growth and development are an imperative. Owing to the pandemic, it is now even more urgent to reduce African countries’ vulnerability by building climate resilience. Given the worsening debt profiles of African nations in the wake of COVID-19, among others, economic recovery plans have set ambitious targets such as large infrastructure build programmes. This makes it an opportune time to turn to green financing initiatives that will help these countries to tap into an investor base looking for exposure to green assets. Although there is no silver bullet and no blueprint to a green economic recovery, it is recommended that African governments enhance efforts to employ the various green growth financing mechanisms presented in this policy briefing (ie, accelerating investments in infrastructure and renewable energy, establishing or revamping green/environmental funds and other market-based mechanisms, ensuring stimulus investments focus on the Green Economy, implementing green fiscal reform, redirecting existing funding, greening the financial sector and developing green segments). In particular, green bonds are one of the most readily accessible and economical options to help raise large amounts of capital for infrastructure development to meet environmental targets in Africa. In addition, to catalyse the transition to a Green Economy, targeted public finance is needed to decrease investment risk, create a stimulus for green investments and leverage private finance for green investments – especially now that private capital has been showing growing interest in supporting the SDGs. With appropriate support, Africa can revitalise its economy using a new and resilient green framework driving national development to leapfrog old development pathways, setting in motion African-owned growth models that are sustainable, inclusive and resilient.

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to Ian Heffernan for peer reviewing this policy briefing.

About CoMPRA

The COVID-19 Macroeconomic Policy Response in Africa (CoMPRA) project was developed following a call for rapid response policy research into the COVID-19 pandemic by the IDRC. The project’s overall goal is to inform macroeconomic policy development in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by low and middleincome countries (LMICs) and development partners that results in more inclusive, climate-resilient, effective and gender-responsive measures through evidence-based research. This will help to mitigate COVID-19’s social and economic impact, promote recovery from the pandemic in the short term and position LMICs in the longer term for a more climate-resilient, sustainable and stable future. The CoMPRA project will focus broadly on African countries and specifically on six countries (Benin, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa). SAIIA and CSEA, as the lead implementing partners for this project, also work with think tank partners in these countries.

Our Donor

This project is supported by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The IDRC is a Canadian federal Crown corporation. It is part of Canada’s foreign affairs and development efforts and invests in knowledge, innovation, and solutions to improve the lives of people in the developing world.