Recommendations:

- Credit ratings agencies should suspend their assessments for developing countries until global production and supply chains return to pre-COVID-19 levels.

- Governments, regulators and central banks must continue to coordinate policy on a continental level to help maintain financial stability and address imminent problems.

- Central banks can prevent the collapse of the private sector using monetised, deficit-financed interventions.

- Developing countries with large informal sectors can leverage digital technologies to ensure that basic financial services are available to their populations, including businesses.

- Policymakers should pay special attention to sequencing in addressing the impact of the pandemic, with the immediate focus being to contain the spread of the virus, treat the infected and provide support to cash-strapped individuals and businesses.

- Additional financing is needed (through borrowing, debt rescheduling or repurposing of spending) to strengthen government capacity to deal with COVID-19 and its impacts.

Executive summary

This briefing tracks some of the major macroeconomic impacts that COVID-19 has had on African economies and how the pandemic has exacerbated historical structural economic deficiencies across the continent. It also provides an early analysis of the second wave and the longer-term implications of COVID-19 for African economies, and offers suggestions on how to combat the negative impacts of the pandemic.

Introduction

COVID-19 has plunged economies around the world into an emerging recession of an unknown depth, resulting from significant disruptions to international trade and commerce. The economic fallout has been particularly acute in Africa, as borrowing costs have risen dramatically off expectations of widespread defaults. Commodity prices have fallen sharply and there have been large foreign financial outflows, coupled with lockdowns and travel bans that have drastically constrained labour markets and economic activity. This has put African economies under severe strain, with many having entered the COVID-19 crisis in an already weak condition. This has been the impact of the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicting a 3.2% economic contraction for the continent in 2020.

The second-round impact of COVID-19 in Africa will be seen in sovereign credit rating downgrades as countries feel the effects of declining fiscal revenues and foreign exchange receipts. This will be accompanied by widening fiscal deficits and rising debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios as countries take on more debt to mitigate the economic effects of the pandemic. This second-round impact will exacerbate domestic shocks in developing economies which are most at risk of defaulting on their debt repayments, causing credit markets to freeze up.1CountryRisk.io, The Second Wave: The Impact of Covid-19 on Sovereign Ratings (Zürich: CountryRisk.io, 2020), https://countryrisk.io/static/pdf/Country Risk_Covid_Impact_on_Ratings_May_2020.pdfMost African countries’ fiscal policy space is already severely restricted, with high levels of debt and significant structural budget deficits.

The first wave

The synchronised, sudden stop in the real global economy, together with radically reduced income sources fundamental to African countries (eg, remittances, tourism, health, transport [and storage], trade, agriculture, public financing and government budgeting, and natural resources), has had the biggest economic impact on African countries to date. The crisis has revealed many tail risks and exposed several structural deficiencies in African economies, among other sovereign default risks and the sudden emergence of the flight-to-quality phenomenon.

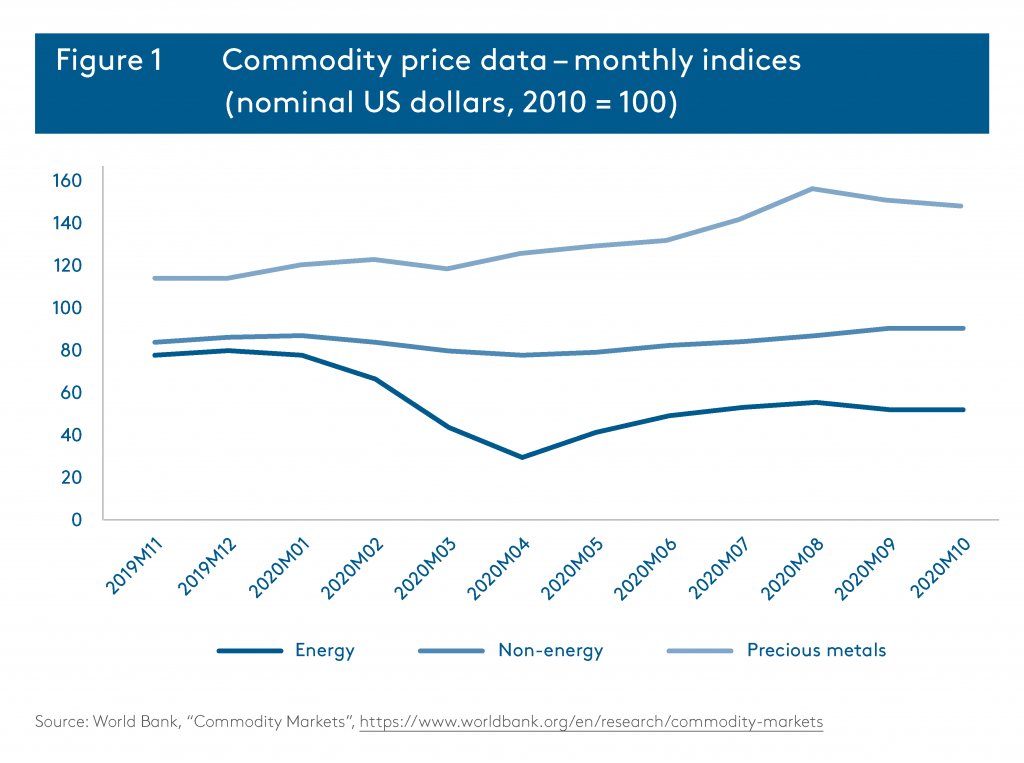

First, in the early stages of the crisis, the contraction in Chinese output, together with the significant impact thereof on global commodity exports and supply chains, exerted negative pressure on already slightly depressed commodity prices.2Shawn Donnan et al., “A Covid-19 Supply Chain Shock Born in China Is Going Global”, Bloomberg (March 20, 2020), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-20/acovid-19-supply-chain-shock-born-in-china-is-going-global.Figure 1 shows the volatility in energy and non-energy (eg, agriculture, fertilisers, metals and minerals) commodity prices, from the start of the pandemic. Such volatility has been especially detrimental to African countries due to their heavy reliance on commodity exports. The breakdown in export markets resulting from the coronavirus pandemic created widespread risk and prompted economic slowdowns in many African economies.

Second, in addition to the fall in commodity prices and related revenues, many African countries experienced a drop in foreign remittances as global economic activity came to a halt in sectors such as construction, hospitality and other service sectors. Remittances have been the largest and most stable source of international financial flows since 2010, accounting for about onethird of total external financial inflows. The World Bank predicts that remittance flows to Africa in 2020 will decline by 23.1% to $37 billion, from $48 billion in 2019. It forecasts that there will be only a 4% recovery in 2021.3World Bank, “COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens”, April 2020, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33634/COVID19-Crisis-Through-a-Migration-Lens.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y.

Third, reduced revenue will be compounded by an expected drop in foreign investment. The volatility in debt markets, exacerbated by the spreading pandemic, is also a function of the pre-COVID-19 macroeconomic and financial environment. After the global financial crisis (GFC), emerging market portfolios became increasingly popular in an environment characterised by low rates and easy money, coupled with prevailing low asset returns in the developed world. Consequently, there were large financial flows into the developing world, with significant amounts going to Africa’s strongest growth economies (Ethiopia and Rwanda, for example). African lenders became increasingly reliant on this foreign financing and thus more leveraged, often incurring non-local currency debt.

Intuitively, more foreign participation during normal times will ensure increased foreign influence during downswings in the form of mass outflows.4International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report: Markets in the Time of COVID-19 (Washington: IMF, April 2020), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2020/04/14/global-financial-stability-report-april-2020.This was evident as major African equity indices lost 10–30% of their value within a two-week period in early March 2020. The magnitude of this drop in value, the speed with which it occurred and the volatility it unleashed in equity markets, were unprecedented. Therefore, even before the pandemic had spread to the continent and before any form of health crisis had emerged, African countries were facing the prospect of a severe economic crisis.

Fourth, the severity of the COVID-19 crisis and its long-term effects will largely be shaped by another major factor contributing to Africa’s vulnerability – limited fiscal space. It is estimated that Africa could lose up to 20–30% of its fiscal revenue,5AU, Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) on the African Economy, report (Addis Ababa: AU Commission, 2020), https://www.tralac.org/news/article/14483-impact-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-on-the-african-economy.html.which could result in an inability to service debt or even trigger a default. In October 2020, Zambia was the first African country to signal that it would default on its loans if investors rejected its request to suspend payments.6Joseph Cotterill, “Zambia Warns It Is Preparing for Default”, Financial Times, October 14, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/e56c2a34-16e4-4974-9df8 -a72c092c5ee2The loss of tax revenues and external finance to fund domestic growth and development programmes, coupled with the external value of the local currency falling, will lead to a deep depression on the continent. It is the inability of African economies to fund their recovery in the wake of the health and economic crises caused by the pandemic that has largely driven investor sentiment. While wealthier economies have the luxury of historically low borrowing costs, most developing nations will find it extremely difficult and expensive to create the fiscal space necessary to deal with revenue losses, and fund health system expenditure and economic stimulus packages. This fiscal shortcoming presents a difficult moral trade-off between lives, livelihoods and debt – something that most African states are grappling with as the virus continues to spread.

Policymakers globally and across the African continent have scrambled to inject liquidity into global and domestic markets through massive fiscal and monetary stimulus packages. For example, South Africa’s COVID-19 economic stimulus package amounted to nearly 10% of GDP.7Haroon Bhorat and Tim Kohler, “Lockdown Economics in South Africa: Social Assistance and the Ramaphosa Stimulus Package”, Brookings, blog, November 20, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/11/20/lockdown-economics-in-south-africa-social-assistance-and-the-ramaphosa-stimulus-package/.Yet not all African countries have the fiscal capacity to provide such countercyclical financing. In Nigeria’s case, for example, a dramatic decline in oil revenue will worsen the government’s already constrained ability to fund the necessary fiscal and monetary stimulus packages. The fallout from this pandemic has the potential to stretch fiscal budgets beyond their current limits.

It remains to be seen how African governments will react to idiosyncratic shocks, such as binding fiscal constraints, widespread defaults, overwhelmed healthcare systems and other socioeconomic demands. It is unclear how capable most African states will be in this regard, given their extremely limited fiscal space and reduced revenues. This will be further complicated by a predicted ‘second wave’ of negative economic impacts resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

The second wave

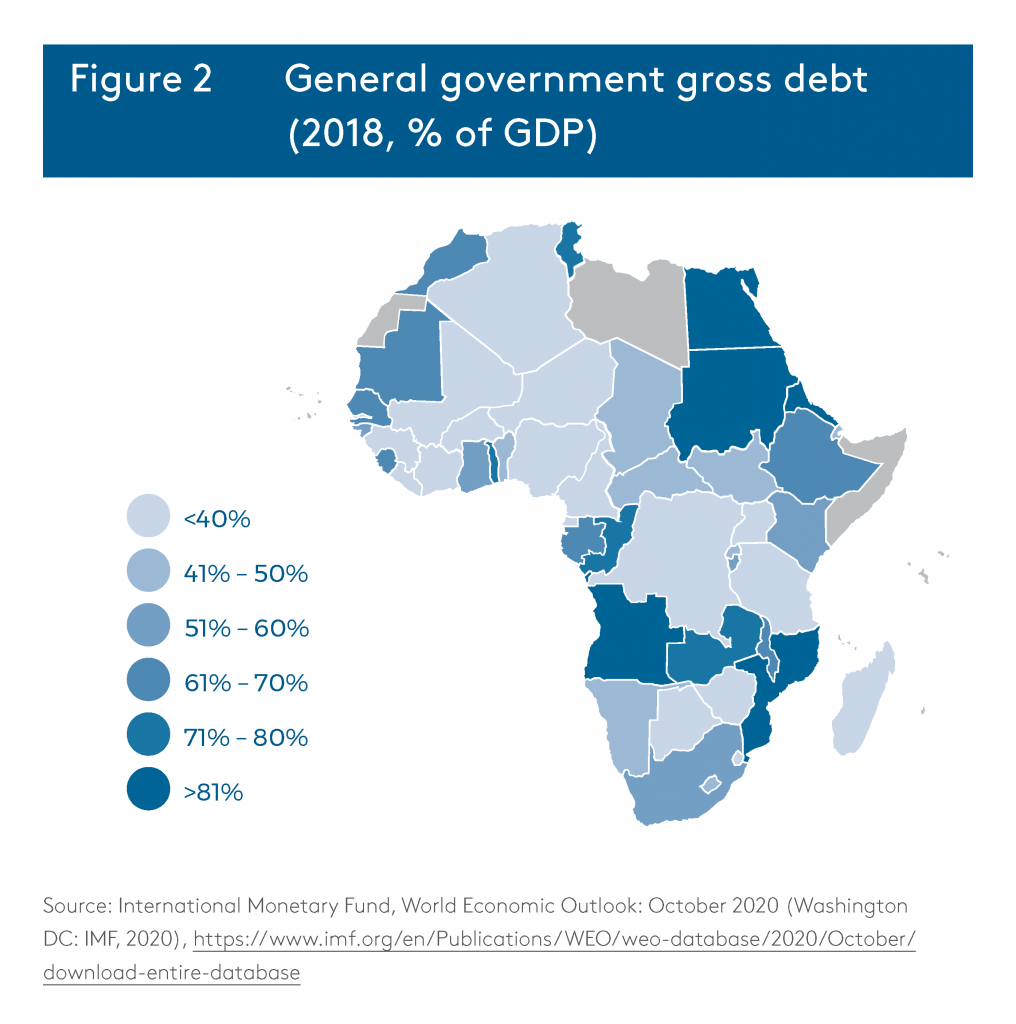

Left with no other options, governments will turn to international markets, which may increase countries’ debt levels. Most countries in Africa will qualify for global relief facilities and humanitarian funds set up to fight COVID-19 – eg, the UN’s $2 billion fund to help the world’s poorest countries or the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative. One-third of African countries are already, or are about to be, at high risk (>60% debt to GDP), owing to recent sharp increases in their debt levels (Figure 2). Normally, debt should be used for productive investment. However, given current circumstances, countries need external sources of finance to support their weak healthcare systems and buffer their economies against the effects of the pandemic, while preventing socioeconomic fallout. An implosion in the stock of external debt and servicing costs is imminent, as is debt restructuring by those unable to repay their creditors.

Major global credit ratings agencies (CRAs) will have a decisive influence on the impact that COVID-19 has on African countries. Many countries have already started to see their ratings being lowered. Post-COVID-19 downgrades could average declines of three investment grades for weaker economies and one investment grade for countries with strong fundamentals.8CountryRisk.io, The Second Wave.From a debt sustainability perspective, the downgrades are the result of an immediate economic contraction, the initial debt-to-GDP ratio, the accumulation of new debt (which widens current fiscal deficits) and the real interest repayment on debt. If economies follow a V-shaped recovery path, the number of actual downgrades could be small. However, in the event of a protracted economic decline, more downgrades could still materialise.9CountryRisk.io, The Second Wave.

COVID-19 has already triggered rating downgrades in seven of the 19 rated sub-Saharan countries since March 2020, including some of Africa’s biggest economies.10African Market News, “Fitch Ratings, Fitch: Outlook on sub-Saharan Sovereigns Is Negative’, (June 13, 2020), https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/outlook-on-sub-saharan-sovereigns-is-negative-12-06-2020.S&P and Moody’s downgraded Ghana’s economic outlook to negative, with the latter affirming the country’s long-term local and foreign-currency issuer and foreign-currency senior unsecured bond ratings at B3. Ghana is vulnerable to shocks because of its high reliance on external financing, in both local and foreign currency, and weak debt affordability. Moody’s and Fitch downgraded Angola to B- with a stable outlook, reflecting the impact of lower oil production and lower oil prices, together with a sharp depreciation of the kwanza (which has increased debt levels and debt servicing costs, while reducing international reserves). S&P revised Nigeria’s outlook to negative, citing the size of the country’s debt and falling reserves, among other factors. Fitch downgraded Nigeria’s long-term foreign-currency issuer default rating (IDR) to B (with a negative outlook) and Zambia’s IDR to CCC.11Ridle Markus (Africa Strategist at Absa Corporate and Investment Banking), interviewed by Consumer News and Business Channel (CNBC) News Africa (March 9, 2020).

These downgrades are attributed to rising risks associated with COVID-19 and these governments’ inability to find funding to cushion their economies while continuing to service their current debts. Credit ratings agencies can suspend their assessments for developing countries until global production and supply chains return to pre-COVID-19 levels.

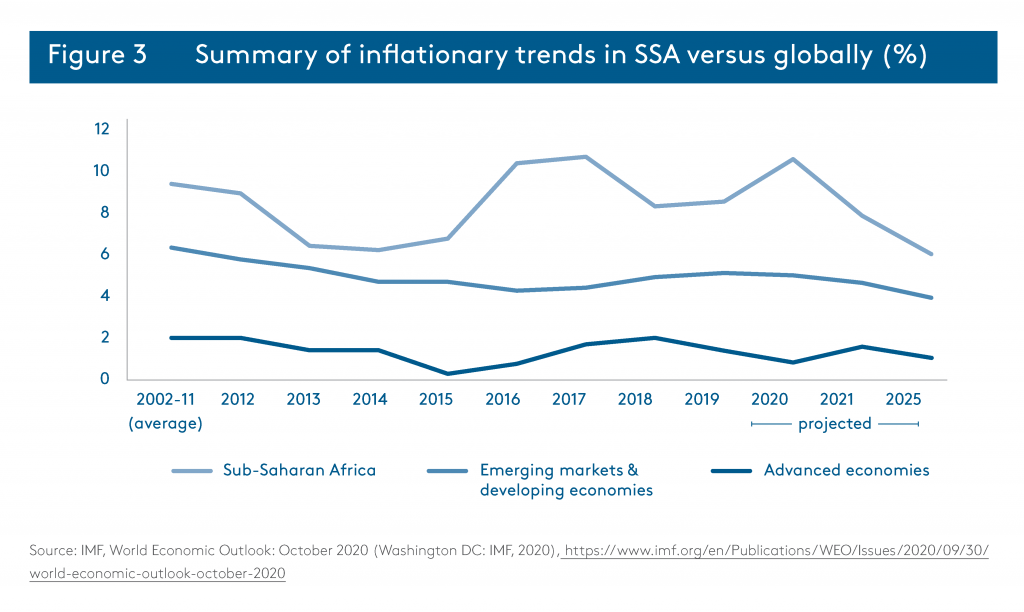

In addition to the tough economic recovery prospects highlighted above, African countries will also be fighting off rising inflation. As the global economy recovers, African countries will experience inflationary increases beyond traditional levels. Since most African countries have open economies, the ban on domestic and international trade (save for essential services) during the pandemic has affected many’s balance of payments (BOP). The current account balances shifted from a deficit position into a surplus position during the first quarter of 2020 in Kenya, Egypt, South Africa, Mauritius, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Botswana, Morocco and Uganda. For example, South Africa posted its first current account surplus since 2003 during the pandemic.12Trading Economics, “Current Account – Africa”, https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/current-account?continent=africa.The central banks of most African countries (including Namibia, Ghana, Kenya, Egypt, Mauritius and South Africa) joined other central banks around the world in cutting interest rates to cushion their economies against the fallout from the pandemic. However, as economies reopen, countries’ BOP will again move towards deficits. This will give rise to a disproportionate increase in the inflation rate in some African economies (Figure 3), which has massive socioeconomic implications for African populations.

Containing the impact – government policy options

The introduction of aggressive stimulus packages by advanced and emerging economies’ central banks – far exceeding conventional interest rate cuts – has resulted in synchronised actions that have helped generate the monetary space needed by developing economies. This increased space will enable them to use monetary policy instruments and macroprudential policy to respond to domestic cyclical conditions, which should further limit financial burdens in countries facing external funding shocks. Governments, regulators and central banks must continue to coordinate policy on a continental level to help maintain financial stability and address imminent problems such as rising corporate leverage, rising bank risk exposure and sovereign exposures, and emerging cross-country distortions to competition in product and capital markets.

African central banks also have a vital role to play in managing the economic fallout from the pandemic. Central banks are the only institutions in developing countries that have balance sheets that are strong enough to prevent the collapse of the private sector, using monetised deficitfinanced interventions. In instances where they are financed through standard government debt, interest rates will have to rise sharply.13Nouriel Roubini, “This Is What the Economic Fallout from Coronavirus Could Look Like”, WEF, April 6, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/ 04/depression-global-economycoronavirus/.In the interests of promoting financial stability, macroprudential authorities would do well to encourage banks to allow distressed borrowers to renegotiate their loan terms (while absorbing the costs of such restructuring by drawing on their capital buffers). Banks must continue to lend to illiquid but still-solvent SMEs. In parallel, authorities should tightly monitor the banking sector’s asset quality to determine the amount of fiscal support (eg, equity injections) that will be required should the effects of the downturn persist.

Developing countries with large informal sectors will have to use new digital technologies14WEF, “Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Financial System: Recommendations for Policy-Makers Based on Industry Practitioner Perspectives”, (Policy Paper, WEF, Geneva, April 2020), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Impact_of_COVID_19_on_the_Global_Financial_System _2020.pdf.to ensure that basic financial services are available to their populations, including businesses. In addition, targeted social and financial relief support for citizens and the business community at large (in particular SMEs) should continue to be provided in order to maintain the economic ties between workers, firms, lenders and borrowers, thereby keeping intact a society’s economic and financial infrastructure.15Arnoud Boot et al., “Corona and Financial Stability 3.0: Try Equity-Risk Sharing for Companies, Large and Small” (Policy Letter 81, Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE, Frankfurt, 2020), https://safe-frankfurt.de/policy-center/policy-publications/policy-publ-detailsview/publicationname/corona-and-financial-stability-30-try-equity-risk-sharing-for-companies-large-and-small.html.Developing countries have rapidly been developing digital payment services in recent years, which provide the opportunity to improve the delivery of targeted relief programmes within the economy.

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic has had a significant impact on African economies to date, largely as a result of reduced revenues. The pandemic has also shown up many of the structural economic deficits in African countries, which have exacerbated the negative economic impacts of COVID-19. Despite this, the potential for further economic hardship remains, as African governments look to provide economic stimulus but face mounting debt stocks, worsening credit ratings and rising inflation.

Nevertheless, governments and external actors can take various policy interventions to help African economies in their post-COVID 19 economic recovery (see Recommendations).

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Dr Oswald Mashindano for his review of this policy briefing.

About CoMPRA

The COVID-19 Macroeconomic Policy Response in Africa (CoMPRA) project was developed following a call for rapid response policy research into the COVID-19 pandemic by the IDRC. The project’s overall goal is to inform macroeconomic policy development in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by low and middleincome countries (LMICs) and development partners that results in more inclusive, climate-resilient, effective and gender-responsive measures through evidence-based research. This will help to mitigate COVID-19’s social and economic impact, promote recovery from the pandemic in the short term and position LMICs in the longer term for a more climate-resilient, sustainable and stable future. The CoMPRA project will focus broadly on African countries and specifically on six countries (Benin, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa). SAIIA and CSEA, as the lead implementing partners for this project, also work with think tank partners in these countries.

Our Donor

This project is supported by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The IDRC is a Canadian federal Crown corporation. It is part of Canada’s foreign affairs and development efforts and invests in knowledge, innovation, and solutions to improve the lives of people in the developing world.