Recommendations

- Boost aggregate demand by implementing expansionary monetary and fiscal policies.

- Continue to implement strategies that ease the liquidity constraints of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), such as credit and tax relief.

- The two sectors most affected by the pandemic in Uganda – industry and services – will need economic stimuli targeting the worst-affected subsectors, such as manufacturing, education, accommodation and entertainment.

- To reverse the increase in poverty levels, the Ugandan government should support MSMEs – which employ the majority of poor people – by providing them with affordable credit and boosting their production and access to markets.

Executive summary

To contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government of Uganda implemented a cocktail of macroeconomic policy responses addressing the contraction of activities in the real and financial sector, and the impact on Ugandans’ livelihoods. Specifically, the government adopted expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to address the impact of the pandemic on the economy, with positive results. First, Uganda’s early response to the COVID-19 pandemic averted a huge cost in human terms. Second, the expansionary monetary and fiscal policies implemented to mitigate the economic impact of the lockdown prevented an adverse dampening of the economy. The expansionary fiscal policy gave businesses temporal liquidity and mitigated the extent of household poverty. In addition, it ensured that the financial sector remained stable, albeit with reduced profitability.

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020 by the World Health Organization. In Uganda, as of 8 June 2021, there have been 53 964 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 383 deaths, while 768 434 vaccines1See World Health Organization, “Uganda”, for the number of confirmed cases, deaths and vaccine doses administered. have been administered. This policy briefing looks at the Ugandan government’s macroeconomic policy decisions to contain the spread of COVID-19, and the impact of these policies on the macroeconomy.

Uganda: Macroeconomic policy choices

The Ugandan government has put in place several strategies to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. These include:

- suspending international flights, except for essential/critical deliveries;

- establishing isolation centres;

- putting in place land-border restrictions, evening curfews and social-distancing measures;

- requiring a 14-day mandatory quarantine period for travellers coming from COVID-19- affected countries;

- restricting domestic travel and encouraging people to work from home;

- closing schools and educational institutions;

- restricting large gatherings, including at places of worship;

- closing non-essential businesses; and

- mandating the wearing of masks.

Given that these measures undermine private sector activities and household welfare, the government has adopted expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to address unintended impacts. These include:

- reducing the central bank rate;

- reducing the reserve requirement ratio;

- encouraging regulatory flexibility at central bank-supervised financial institutions (SFIs) that extend loan-restructuring services on a case-by-case basis;

- directing SFIs to defer dividend payments;

- buying treasury bonds held by microfinance deposit-taking institutions and credit institutions to ease liquidity; and

- increasing the daily transaction limit of mobile money (MM) operators; and reducing MM and other digital charges’ payment charges.

With regard to fiscal policy, it introduced tax exemptions, social protection and private sector relief funds through the Uganda Development Bank, and increased public debt.

Impact of COVID-19 policy responses on the macroeconomy

Impact on the real sector

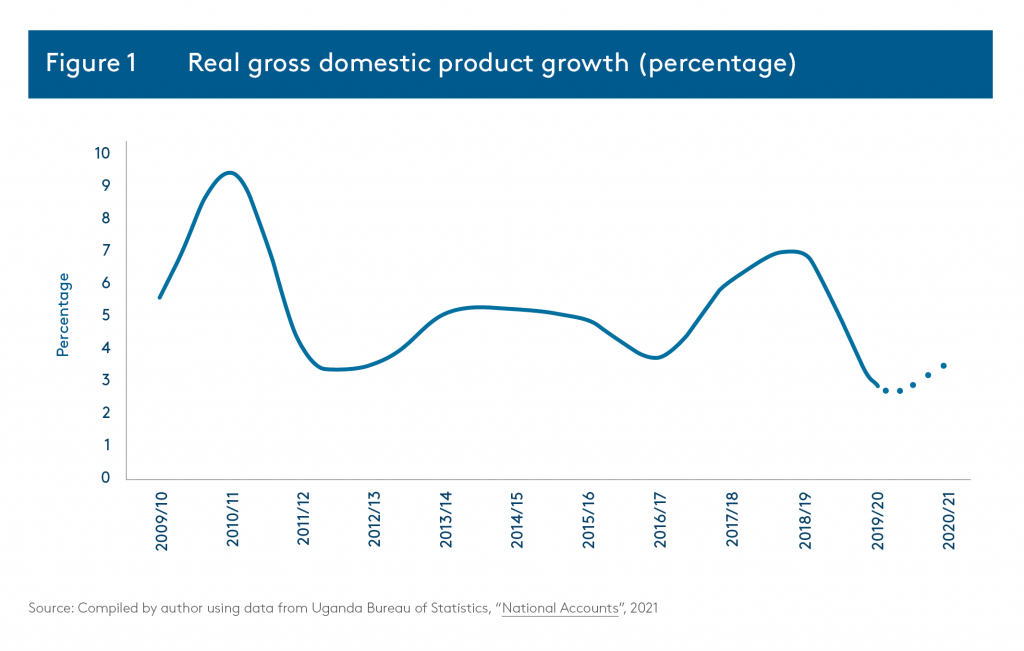

With regard to the macroeconomic effects of COVID-19, the pandemic resulted in reduced real gross domestic product (GDP) growth from 6.8% in the financial year (FY) 2018/19 to 2.9% in FY 2019/20 (see Figure 1). This was far lower than the projected growth of 6.3% for FY 2019/20.

The dampened growth was owing to reduced domestic demand for domestically produced commodities and exports as a result of disruptions in the supply chains of goods, services and labour.

A sectoral disaggregation shows that industrial, services and agriculture sectoral growth dropped from 10.1%, 5.7% and 5.4% respectively in FY 2018/19 to 2.2%, 2.9% and 4.8% in FY 2019/20. The sluggish growth in the services sector was a result of the closure of the education, accommodation and entertainment subsectors. The industrial sector slowdown was on account of the sluggish growth in the manufacturing, mining and construction subsectors, which in FY 2019/20 grew by only 1.3%, 0.2% and 3.8% respectively, down from the 7.8%, 33.4% and 14.2% recorded in FY 2018/19.2Republic of Uganda, Background to the Budget FY2019/20: Industrialisation for Job Creation and Shared Prosperity (Kampala: Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, June 2019). As for the agriculture sector, it remained relatively resilient in the face of the COVID-19 headwinds, with growth decreasing by 0.6% to 4.8% in FY 2019/20. Nonetheless, this was still lower than the 5.3% recorded in FY 2018/19, partly on account of the locust invasion and floods in some parts of the country, in addition to low productivity.3Republic of Uganda, Background to the Budget FY2020/21: Stimulating the Economy to Safeguard Livelihoods, Jobs, Businesses and Industrial Recovery (Kampala: Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, 2020).

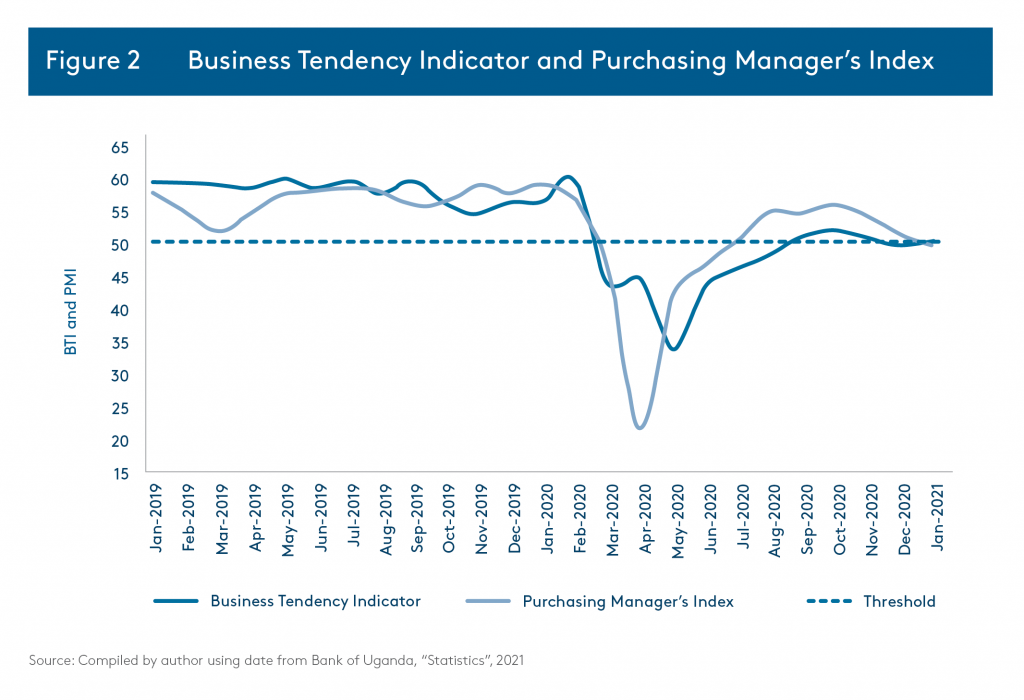

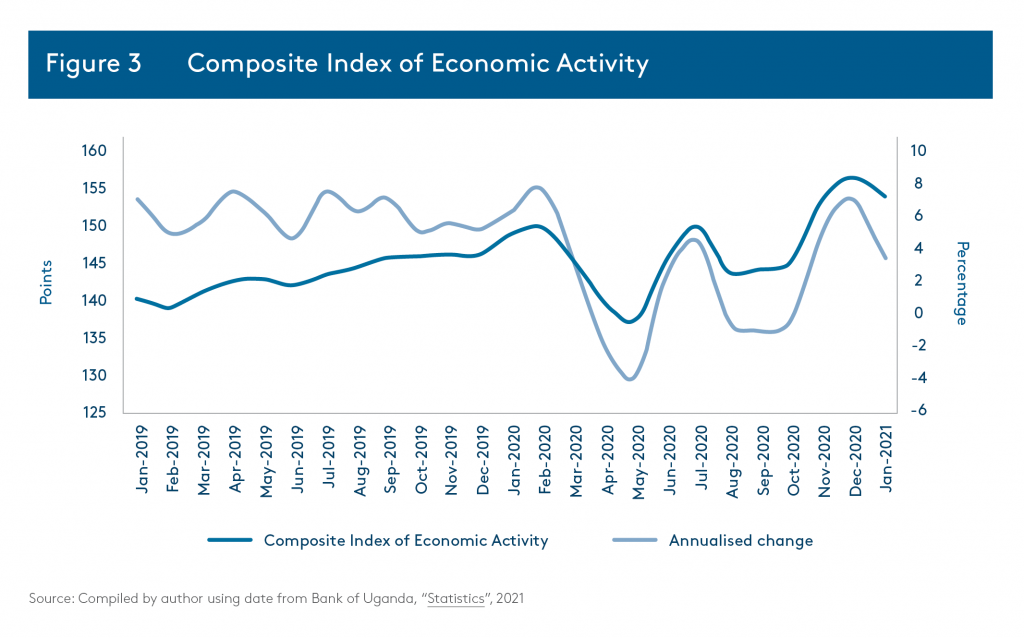

This weak sectoral performance is evident in the indicators of economic activity (Figures 2 and 3). The Purchasing Manager’s Index4The PMI is a composite index, calculated as a weighted average of five individual sub-components: new orders (30%), output (25%), employment (20%), suppliers’ delivery times (15%) and stocks of purchases (10%). It gives an indication of business-operating conditions in the Ugandan economy. A PMI above 50.0 signals an improvement in business conditions, while readings below 50.0 show a deterioration. The PMI is compiled monthly by Stanbic Bank Uganda. (PMI) dropped below the 50 PMI threshold to 45.3 in March and to 21.6 in April 2020, the lowest it has been since its inception (see Figure 2). While the PMI improved to 41.9 in May, economic actors had clearly factored COVID-19 distortions into their decisions, implying compromised output, reduced new orders and lower staffing levels. In addition, from March–June 2020 the Composite Index of Economic Activity5The CIEA is an index that is correlated with the current level of economic activity (such as real GDP). It is constructed using seven variables: private consumption (estimated by VAT); private investment (estimated by gross extension of private sector credit); government consumption (estimated by its current expenditure); government investment (estimated by its development expenditure); excise duty; exports; and imports. (CIEA) annualised growth averaged -0.04%, compared to 6% over the same period in 2019 (see Figure 1). Both the PMI and CIEA showed that the dampened economic environment in March–June 2020 was partly attributable to the aggressive COVID-19 containment measures, temporary company closures, subdued demand and travel restrictions. Similarly, the Business Tendency Index (BTI)6The BTI measures the level of optimism that executives have about the current and expected outlook for production, order levels, employment, prices and access to credit. This index covers the major sectors of the economy, namely construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, agriculture and other services. An overall BTI above 50 indicates an improving outlook and below 50 a deteriorating outlook. dropped below the 50 threshold for the first time in March, and stayed there until August 2020

(see Figure 2). This implies that executives were pessimistic about the business outlook on account of COVID-19 containment measures and uncertainty around the speed of the postCOVID economic recovery.

Impact on livelihoods

The economywide lockdown has had the biggest impact on MSMEs, which constitute 90% of the entire private sector. MSMEs, which typically operate in the informal sector, contribute about 75% to GDP and employ over 3 million people.7Anup Singh, “MSME Finance in Uganda: Status and Opportunities for Financial Institutions” (Briefing Note 169, MicroSave Consulting, Nairobi, March 2017). They tend to be fragile and, as such, have been severely affected by the lockdown. For example, 46% (manufacturing), 43% (hospitality) and 41% (trade and services) workers have been pushed to below the poverty line.8UN in Uganda, Leaving No-One Behind: From the COVID-19 Response to Recovery and Resilience-Building – Analyses of the Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 in Uganda (Kampala: UN in Uganda, June 2020). Overall, the World Bank estimates that the number of people living below the poverty line in Uganda are likely to rise from 8.7 million to 11.7 million – a 34.5% increase.9World Bank, “Uganda’s GDP Contracts Under COVID-19, Investing in Uganda’s Youth Key to Recovery”, Press Release No. 2021/066/AFR, December 2, 2020. In an effort to lessen COVID-19-induced livelihood distortions, the Ugandan government has adopted various fiscal and monetary policy regimes. However, these have been undermined by the absence of a clearly defined database to appropriately target vulnerable households and MSMEs.

Impact on the monetary sector

With regard to the monetary sector, commercial lending rates dropped from 19.1% in February 2020 to 17.8% and 17.7% in March and April 2020 respectively. This was on account of the government’s accommodating monetary policy and the subdued demand for credit. However, lending rates picked up shortly afterwards, peaking at 20.9% in July 2020 and tapering off to 17.4% in January 2021. While historically low in the Ugandan context, lending rates remain high as structural rigidities in the financial sector – especially high operational costs and risk-averseness among creditors – persist. While interest rates have dropped, private sector credit growth has largely been weak as well, for the same reason.

The financial sector has been resilient, albeit with reduced profitability, owing to the Bank of Uganda’s (BoU) extending credit and liquidity relief measures to the sector. Besides the BoU’s monetary and macro-prudential policy actions, financial sector resilience was also supported by the build-up of deposits driven by fiscal expansion and increased investment in government securities amid COVID-19-induced risk averseness to private sector lending. However, challenges remain. It is unclear how the BoU will manage the transition once its monetary and macroprudential policy actions have been terminated, as this will have a bearing on the stability and robustness of Uganda’s financial sector in the short to medium term.

Impact on the external sector

With regard to the external sector, the pandemic resulted in an improvement in the current account. Specifically, the current account deficit as a percentage of GDP dropped from 7% in FY 2018/19 to 6% in FY 2019/20. This was partly owing to reduced imports – from 19.9% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 16.8% in FY 2019/20 – following trade disruptions. However, unlike the goods trade, the trade-in-services deficit worsened from 1% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 2.8% in FY 2019/20. This was partly on account of a reduction in tourism receipts – from 3.5% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 2.4% in FY 2019/20. Overall, the trade deficit as a percentage of GDP contracted from 9.4% in FY 2018/19 to 9.3% in FY 2019/20, against a net income of 3.3% of GDP that could not finance the trade deficit.

Given net foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows and capital transfers that stood at 2.6% and 0.2% of GDP respectively, among other factors, the current account remains manageable. This is despite the fact that both FDI and capital transfers contracted in FY 2019/20. FDI in FY 2019/20 as a percentage of GDP shrank by 0.9 percentage points to 3.5%, compared to FY 2018/19.

Specifically, FDI reduced from $284.92 million in the quarter ending December 2019 to $217.17 million, $178.96 million and $209.51 million respectively in the quarters ending March, June and September 2020. Similarly, capital transfers as a percentage of GDP dropped from 0.3% in FY 2018/19 to 0.2% in FY 2019/20. Specifically, capital transfers went from $32.57 million in the quarter ending December 2019 to $16.16 million, $8.75 million and $33.52 million respectively in the quarters ending March, June and September 2020. The contraction in both capital transfers and FDI is a result of the global economic slowdown partly attributable to COVID-19. However, although both FDI and capital transfers contracted in FY 2019/20, they did help to mitigate the vulnerability associated with Uganda’s relatively sizeable current account deficit in FY 2019/20 and contribute to the build-up of the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves.

Meanwhile, tourism receipts as a percentage of GDP fell from 3.5% in FY 2018/19 to 2.4% in FY 2019/20. Specifically, tourism receipts went from $312.71 million in the quarter ending December 2019 to $237.54 million, $0.00 million and $42.29 million respectively in the quarters ending March, June and September 2020. The slowdown in tourism earnings was caused by the COVID19-induced closure of Uganda’s airspace.

Impact on the fiscal sector

The fiscal deficit increased from 5% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 7.5% of GDP in FY 2019/20. This increase was partly on account of a rise in government spending – from 18.9% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 21.2% in FY 2019/20. This increase in spending was partly on account of COVID-19 and the locust invasion.10Locusts invaded eastern Uganda in the spring of 2019, resulting in the degeneration of rangelands and delaying the start of the planting season, thereby increasing the likelihood of food poverty, malnutrition and cattle rustling. See World Bank, “FAQs: Uganda Emergency Desert Locust Response Project”, October 2019. Yet tax revenue collection fell from 12.4% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 11.6% in FY 2019/20 – a contraction of 0.8%. Similarly, grants dropped from 0.9% of GDP in FY 2018/19 to 0.6% in FY 2019/20. The drop in tax revenue collection was partly on account of COVID19-containment and tax-relief measures. Annualised tax revenue growth was dampened in March–June FY 2019/20, growing by 0.2%, -25.7%, -30.6% and -15.9% respectively. Specifically, domestic taxes on a month-on-month (m-o-m) basis contracted by -70.6% and -12% in April and May respectively. This was partly on account of subdued value added tax (VAT) collections, which grew by -7.33%, -22% and -10.4% on a m-o-m basis in March, April and May FY 2019/20 – at the peak of the COVID-19 containment measures. Another casualty of COVID-19-related restrictions on the international movement of goods and services was international taxes, which contracted in March and April FY 2019/20, growing on a m-o-m basis by -7.4% and -43.5% respectively. Specifically, VAT grew by -9% and -41% respectively in March and April FY 2019/20. Excise duty grew by -6% and -45% respectively over the same period. In addition, withholding tax grew by -27.8% and -33.5% in March and April FY 2019/20. Consequently, tax revenue as a percentage of GDP was 1.9% lower than the 13.5% budgeted tax revenue in FY 2019/20.

The poor tax revenue performance as a result of COVID-19 led to an increased appetite for public debt. The stock of public debt went from $12.55 billion in FY 2018/19 to $15.27 billion in FY 2019/20 – a 21.7% increase. As a percentage of GDP, public debt rose from 35.3% in FY 2018/19 to 41% in FY 2019/20. Specifically, external debt increased by 25.1%, from $8.35 billion in FY 2018/19 to $10.45 billion in FY 2019/20. Domestic debt, on the other hand, increased by 14.8% – from $4.20 billion to $4.82 billion. The increase in public debt in FY 2019/20 was on account of the distortionary effect of COVID-19 on the economy and the containment measures adopted, which resulted in a revenue shortfall. Furthermore, emergency measures to shore up the healthcare sector and protect the livelihoods of the vulnerable amid the revenue shortfall resulted in increased public debt uptake. COVID-19 thus has partly created the following risks: public debt vulnerability, especially with regard to external debt; a 0.9% increase in international reserve requirements to fulfil short-term debt maturities; and an increase in private sector crowding-out, especially in terms of domestic public debt.

Impact on poverty

While many of the policy responses succeeded in moderating the human cost of COVID-19, the containment measures dissipated the gains made thus far in Uganda’s structural transformation and fight against poverty. The reversal in economic progress was in part owing to the contraction in the industrial and services sectors. This, in turn, led to increased unemployment and a 34.5% rise in the number of people living below the poverty line – from 8.7 million to 11.7 million.11World Bank, ‘”Uganda’s GDP Contracts”.

Fiscal policy did give businesses a temporary liquidity shield in the face of a dampened aggregate demand and risk-averse creditors. The launch of the Emyooga Fund – a UGX12Currency code for the Ugandan shilling. 165 billion ($45.2 million) poverty-eradication scheme – also mitigated the extent of household poverty. However, this added to the tax revenue shortfall, which in turn increased government appetite for debt.

Conclusion

Uganda’s early response to the COVID-19 pandemic averted a huge human cost. The monetary and fiscal policies the government implemented to mitigate the impact of the lockdown on the economy shielded it from adverse dampening effects. The expansionary fiscal policy gave businesses temporal liquidity and mitigated the extent of household poverty, while the expansionary monetary policy ensured a stable financial sector, albeit with reduced profitability. The two most affected sectors – industrial and services – will need an economic stimulus targeting the worst-affected subsectors, such as manufacturing, education, accommodation and entertainment. To reverse the increase in poverty levels, the Ugandan government should support MSMEs by providing them with affordable credit and improved government support, boosting production and access to markets.

Acknowledgement

The African School of Economics, South African Institute of International Affairs, CSEA and our think tank partners acknowledges the support of the International Development Research Centre for this research paper and the CoMPRA project.

About CoMPRA

The COVID-19 Macroeconomic Policy Response in Africa (CoMPRA) project was developed following a call for rapid response policy research into the COVID-19 pandemic by the IDRC. The project’s overall goal is to inform macroeconomic policy development in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by low and middleincome countries (LMICs) and development partners that results in more inclusive, climate-resilient, effective and gender-responsive measures through evidence-based research. This will help to mitigate COVID-19’s social and economic impact, promote recovery from the pandemic in the short term and position LMICs in the longer term for a more climate-resilient, sustainable and stable future. The CoMPRA project will focus broadly on African countries and specifically on six countries (Benin, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa). SAIIA and CSEA, as the lead implementing partners for this project, also work with think tank partners in these countries.

Our Donor

This project is supported by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The IDRC is a Canadian federal Crown corporation. It is part of Canada’s foreign affairs and development efforts and invests in knowledge, innovation, and solutions to improve the lives of people in the developing world.