Recommendations

- Greater benefits from fiscal policy could be obtained by better targeting spending towards the most vulnerable households. Lower-income households consume a greater proportion of their (supplemented) income than higher-income households do, and particularly on goods and services produced domestically. This enhances the fiscal multiplier effect by minimising leakages into imports, luxury consumption and savings.

- Growth of the agricultural sector should continue to be prioritised through monetary policy. This will help to keep food prices low and maintain food security.

- To reduce the negative effect of inflation on real incomes, contractionary monetary policy should be implemented during a period of economic growth.

Executive summary

This policy brief outlines the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Benin. We focus on the monetary and fiscal policy implemented by the government of Benin and the Central Bank of West African States. Government and the bank acted rapidly to contain the spread of the virus to minimise any adverse economic consequences. Fiscal policy took the form of cash transfers and subsidies for households and firms. Monetary policy expanded liquidity through banking and microfinance institutions. A portion of liquidity was specifically allocated to the agricultural sector to ensure food security. The expansion in liquidity increased consumer prices, which increased the cost of living and could potentially increase poverty. Future fiscal policy should better target those households most impacted by the price increase.

Introduction

The government of Benin has taken decisive action to limit the negative health and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. This policy brief outlines the policy actions the government and the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) have taken to limit the negative economic consequences in Benin. In particular, the brief focuses on fiscal and monetary policy. The expansionary monetary policy led to an increase in consumer price inflation. However, less of a sustained increase in the Food Price Index (in contrast to many African countries) can be observed. If not matched by a similar increase in wages, an increase in prices has caused real household incomes to decline.

The government of Benin complemented its monetary policy with expansionary fiscal policy in the form of cash transfers and subsidies for household and business expenses. The fiscal policy had the effect of stimulating aggregate demand by increasing consumption and also helped offset any decline in real income by reducing the (non-essential) expenses of households and firms. Greater benefits from fiscal policy could be obtained by better targeting spending towards the most vulnerable households. Vulnerable households tend to spend more on domestic goods, thus enhancing the fiscal multiplier by minimising leakages into imports, luxury consumption and savings.

Future policy needs to continue to consider inflation and the negative effect it has on real incomes. In order to avoid the future negative effects of prolonged inflation, the government of Benin and the BCEAO will need to implement contractionary monetary policy. To help prevent defaults on the newly issued debt, this contractionary monetary policy should be implemented during a period of economic growth and high aggregate demand. The growth in gross domestic product (GDP) for 2020/2021 suggests that Benin’s economy is already recovering from the reduction in growth in 2019/2020. This suggest that contractionary policy can likely be implemented in the next year or two. Future government spending should be targeted towards the sectors most likely affected by the initial negative income shock, such as the hospitality and industrial sectors, in order to ensure the recovery of all sectors. In addition, growth in the agricultural sector should be prioritised in order to keep food prices low and maintain food security.

COVID-19 in Benin and its effects on the economy

The spread of COVID-19 has been relatively minimal in Benin. As of October 2022, there have been 161 deaths from COVID-19, which is 1.33 deaths per 100 000 people. The average for Africa is 13.33 deaths per 100 000, and globally there have been 43.deaths per 100 000.1World Health Organization, “WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard”.

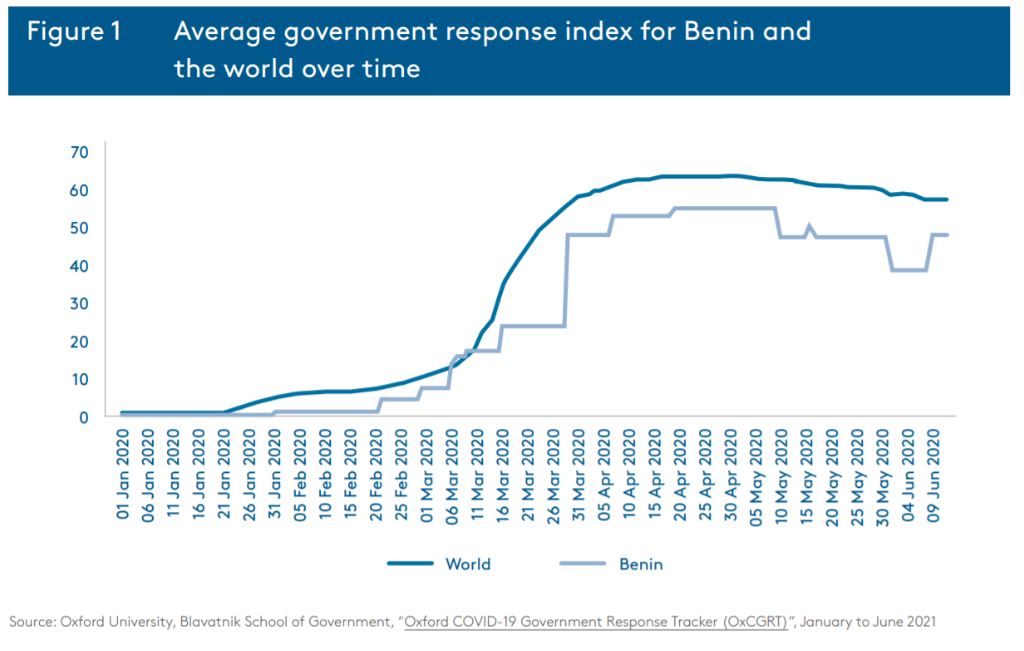

The government and the BCEAO acted swiftly to contain the adverse health and economic consequences of the pandemic. The magnitude of the government’s response to the pandemic was measured using the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) dataset.2

OxCGRT reports publicly available information on 15 indicators of government responses. The data is collected from sources such as news articles, government press releases and briefings. These are identified via internet searches by a team of more than 100 Oxford University students and staff. OxCGRT records the original source material so that coding can be checked and substantiated. Figure 1 plots the government response index over time in Benin and the average for the rest of the world. As seen in the figure, Benin policy response closely followed that of the rest of the world. The figure points to a strong policy response by the government of Benin.

Despite the government’s rapid response, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe effect on Benin’s economy. The GDP growth rate fell from 6.9% in 2019 to 3.9% in 2020. In 2021, the growth rate rebounded to 6%. The industrial, service and agricultural sectors all experienced a decline in growth rates in 2019/2020. The industrial and agricultural sectors experienced large declines in growth rates from 5.2% to 1.8%, and from 13.6% to 5.2% respectively. The growth rate of the service sector declined from 5.1% to 3.4% in 2019/2020. This is particularity concerning given that services is Benin’s largest sector, comprising 54.5% of GDP in 2019. In 2021, the growth rate of GDP and the three sectors have returned to close to their pre-pandemic levels.

Benin also experienced a large decrease in the growth rate of consumption – from 3.8% to 1.6% over the past two years. This decrease is attributed to a large decline in private consumption, the growth rate of which declined from 3.5% to negative 0.2%. This decline in the growth rate was offset by a large increase in public consumption, the growth rate of which increased from 5.8% to 14.4%. This may be attributed to the expansionary monetary and fiscal policy the government and the BCEAO implemented.

Benin also experienced a large decline in the growth of investment. In 2019, investment represented 33.2% of GDP. From 2019 to 2020, the growth in investment was 2.1%, down from 10.2% in 2018/2019. The decline in investment likely reflects the global negative income shock combined with uncertainty as to how the pandemic was going to affect African countries. From 2020/2021, the growth rate of investment increased dramatically to 13.7%.

The large drop in global demand can be seen in the large reduction in the growth rate of exports in Benin. The growth rate of exports decreased from 8.6% in 2018/2019 to -25% in 2019/2020. The growth rate of imports also decreased from 3.4% to -19.8%. The reduction in exports represents a large contribution to the decline in the growth rate of the GDP in 2019/2020. However, the growth rate of exports and imports for 2020/2021 increased to 17.9% and 15% respectively.

Money supply and inflation

As described in more detail below, the government and the BCEAO implemented an expansionary monetary policy, which resulted in a dramatic expansion of the money supply. Broad money supply increased by 14% from January 2020 to January 2021.3

The broad money data comes from the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics dataset (line 35L..ZK) and is defined as the sum of currency outside banks; demand deposits other than those of the central government; the time, savings, and foreign currency deposits of resident sectors other than the central government; bank and traveller’s cheques; and other securities, such as certificates of deposit and commercial paper.At the time of writing, towards the end of 2021, the money supply in Benin was at its highest level by far in the past five years.

The expansion of the money supply led to high levels of inflation in the first quarter of 2020. According to data from the Food and Agricultural Organization, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the highest it has been in the past five years. If wages remain the same, rising prices will contribute to a decline in household wealth and potentially an increase in poverty. The International Labour Organization estimates that unemployment in Benin increased from 2.32% in 2019 to 2.54% in 2020. Rising prices will be especially tough on the newly unemployed. As described in detail below, the government’s fiscal policy, which includes energy subsidisation and cash transfers, will alleviate the additional costs incurred by households.

The price of food is much more volatile than the Consumer Price Index. However, there does not appear to have been significant food price inflation in the early months of 2020 as per the Food Price Index. This is likely explained by government and BCEOA policy targeting the agricultural sector and designed to keep farms in operation and domestic food supply and food prices stable.

Fiscal policy

The government has significantly increased spending to alleviate the pandemic’s adverse consequences on the economy and the health of the people of Benin. The spending is meant to alleviate poverty and stimulate aggregate demand. According to the International Monetary Fund, the total value of the fiscal stimulus in 2020 was FCFA4FCFA is the currency code for Central African franc. 244.5 billion ($434.1 million). The spending issued to households consists of direct cash transfers and subsidies for electricity and water for all citizens totalling FCFA 5.76 billion ($10 million). The government also made some concessions in terms of tax on motor vehicles, exempting households who had not yet paid their annual amount in 2020, and issuing those that had paid a credit for 2021.

Government spending has aimed at keeping businesses in operation. In particular, the government allocated funds to cover 70% of gross salaries for three months. In addition, it spent FCFA 4.1 billion ($7.5 million) on covering electricity bills for three months for hotels and travel agencies. Travel agencies were exempted from paying commercial rent for a three-month period. As the hospitality sector was severely affected by the pandemic, this sector should be continuously monitored to ensure a healthy recovery.

Monetary Policy: Central Bank of West African States

The West African Economic and Monetary Union has taken pre-emptive steps to meet the demand for liquidity in the banking sector and to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic on the economy. As of March 2020, the BCEAO raised the liquidity available to banks at its weekly and monthly auctions, allowing average refinancing rates to remain relatively close to the floor of the monetary policy corridor of 2.5%. This was followed by the adoption of a full allotment strategy at a fixed rate of 2.5%, which allowed banks to fully satisfy their liquidity needs at a lower rate. To further increase liquidity, the BCEAO announced in March 2020 that 1 700 private companies prequalified for its extension of the collateral framework to access BCEAO refinancing to include bank loans.5KPMG, “Benin: Government and Institution Measures in Response to COVID-19”, April 28, 2020.

The BCEAO has also put in place numerous policies to ease the requirements of prudential banking legislation on financial institutions and companies. These policies preclude banks from classifying loans as non-performing if they had not been serviced due to COVID-19-related problems. The BCEAO has also set up a system for monitoring firm experiencing financial trouble as a result of COVID-19.6Banque Centrale des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (BCEAO), “Espace COVID-19”.

Monetary Policy: Government of Benin

The government of Benin has also implemented measures to increase bank and microfinance lending to the agriculture sector and to small-, medium- and micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs). In June 2020, the Council of Ministers established a FCFA 30 billion ($55 million) subsidy fund to support a FCFA 100 billion ($185 million) interest-free line of financing for these sectors via banks and the decentralised financial system.7Government of Benin, “Minutes of the Council of Ministers of 10 June 2020”, June 10, 2020. The fund aims to facilitate lending by banks and microfinance institutions to the agricultural sector.

The government has stimulated bank lending by guaranteeing 50% of new credit issued, to the value of FCFA 78.6 billion ($145 million), according to the International Monetary Fund. To stimulate lending to SMMEs, the government has increased liquidity to the National Microfinance Fund. Moreover, the maximum interest rate was capped at 12% instead of the usual 20% average. Special attention has also been paid to expanding credit in the agricultural sector. Liquidity was allocated to the National Fund for Agricultural Development (FNDA), which makes funds available to the agricultural sector via banks and microfinance institutions. Moreover, subsidized loans were made available to the agricultural sector at a rate of 2%.8Government of Benin, “Minutes of the Council of Ministers of 10 June 2020”.

Conclusion

This brief outlined the government of Benin and the BCEAO’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The economic-policy response focused heavily on the expansion of credit. The expansion of credit can play an important role in stimulating the economy by allowing companies to increase spending and avoid bankruptcy during a period of decreased demand. However, the expansion of credit puts upward pressure on prices, thus pushing vulnerable households into poverty. The expansion of credit in the agricultural sector somewhat avoids the issue of higher prices pushing individuals into poverty because increased food production keeps food prices low while the prices of other goods rise. Given that vulnerable households spend more of their income on food than non-vulnerable households, they are less affected by an increase in non-food prices. A more detailed analysis of which prices were most affected by the increase in liquidity will facilitate policy that will help minimise the negative impact of inflation on real incomes.

The government’s fiscal policy offsets the negative effects of a price increase by reducing household expenses and providing income in the form of direct cash transfers.

Compared to non-vulnerable households, vulnerable ones tend to spend any increased income that may come in more easily, multiplying by a greater degree the effect of the spending on GDP. For this reason, government spending should primarily target vulnerable households.

In order to avoid future negative effects of prolonged inflation, the government and the BCEAO will need to implement contractionary monetary policy during a period of economic growth and high aggregate demand to help prevent defaults on the newly issued debt. Government spending should target sectors most likely to be affected by this policy.

Acknowledgement

The African School of Economics, South African Institute of International Affairs, CSEA and our think tank partners acknowledges the support of the International Development Research Centre for this research paper and the CoMPRA project.

About CoMPRA

The COVID-19 Macroeconomic Policy Response in Africa (CoMPRA) project was developed following a call for rapid response policy research into the COVID-19 pandemic by the IDRC. The project’s overall goal is to inform macroeconomic policy development in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by low and middleincome countries (LMICs) and development partners that results in more inclusive, climate-resilient, effective and gender-responsive measures through evidence-based research. This will help to mitigate COVID-19’s social and economic impact, promote recovery from the pandemic in the short term and position LMICs in the longer term for a more climate-resilient, sustainable and stable future. The CoMPRA project will focus broadly on African countries and specifically on six countries (Benin, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa). SAIIA and CSEA, as the lead implementing partners for this project, also work with think tank partners in these countries.

Our Donor

This project is supported by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The IDRC is a Canadian federal Crown corporation. It is part of Canada’s foreign affairs and development efforts and invests in knowledge, innovation, and solutions to improve the lives of people in the developing world.