After the high point of last year’s tenth year anniversary celebrations, it was back to business as usual at the 29 January 2014 APRM Forum meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on the fringes of the African Union Summit. Only one new member country – Equatorial Guinea – joined the mechanism, contrary to the expectations that both Cape Verde and Côte d’Ivoire would also accede. In addition, only two existing members – South Africa and Mozambique – presented their progress reports, despite the expectation that three others would do so as well.

While the accession by Equatorial Guinea raised eyebrows among some observers, this could be a welcome signal that the country might, at last, be willing to begin an internal and regional discussion around governance concerns.

The absence of the presidents of Benin, Burkina Faso and Sierra Leone at the Forum meant that these countries were removed from the final programme.

Conceptualised as a continental instrument for improving governance in Africa across four thematic areas (democracy and political governance, economic governance and management, corporate governance and socio-economic development), the APRM was launched in March 2003 as part of the overarching New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), aimed at putting Africa on a more sustainable development path. Referring to numerous international and African governance standards and utilising a comprehensive questionnaire, member states review their own performance as well as open themselves up to scrutiny by African experts. The two review processes are merged and published in a single report and the head of state is then reviewed by his or her peers. The participating government pledges to tackle the governance deficiencies revealed while building on best practices unearthed in the course of the review.

In African politics, as in the rest of the world, this was and remains unprecedented. Moving away from perceptions of African leaders being members of an ‘old boys’ club’, the APRM has been instrumental in creating systems of transparency, accountability, national dialogue and mutual co-operation on the way forward.

After ten years, however, interest from civil society, donors, journalists and, most importantly, member states themselves for this innovative initiative has waned.

The APRM has succeeded in publishing, for the most part, frank and comprehensive review reports. But governance problems are not being addressed as decisively as hoped, and unrealistic, expensive National Programmes of Action are hampering the implementation of remedial and redress programmes. The APRM is also failing to capture much attention outside government circles.

Most worrying for the mechanism and its supporters is that although 34 heads of state are ostensibly keen to improve their governance systems, most rarely attend ‘peer review’ consultations. Also, not enough is being done at this level to share lessons and work together on finding solutions to vexing governance problems. Without this high level engagement and support, the APRM is currently struggling to make a real impact on governance in the region.

The APRM’s evident loss of momentum is of concern. When Liberia’s President, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, was installed as the head of the APRM Forum in May last year, some expressed cautious optimism for positive change. Although seven months have passed since her appointment, she has not yet stamped her authority on the mechanism. Yet AU insiders say that her style is one of quiet housekeeping behind the scenes, before results of her work become visible.

An important institution in the country review processes, the APR Panel of Eminent Persons, once again underwent changes at this summit. In spite of only being appointed as the Panel’s chairperson in May 2013, Barrister Akere Muna, a prominent Cameroonian lawyer and vice-chair of Transparency International, was replaced by Ambassador Fatuma Ndangiza, deputy CEO of the Rwandan Governance Board. Ambassador Ashraf Rashed from Egypt became vice-chair of the Panel. Leaving the Panel are Barrister Muna, Barrister Julienne Gnelenga from Congo-Brazzaville and Professor Amos Sawyer from Liberia. They will be replaced by Ambassador Edem Kojo from Togo, Professor Abo Mengeuel from Sudan and Mr Mahamoud Yossouf Khayal from Chad.

No news unfortunately emerged about the proposed increase of capacity at the APRM’s main administrative body, the Secretariat. In spite of the official approval to hire new staff in May 2013, the long-awaited recruitment process has not yet started, which is concerning. Increased capacity would strengthen the Secretariat’s ability to respond to the needs of the mechanism’s ever-increasing membership.

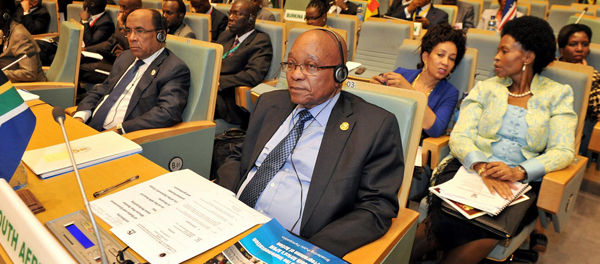

It is against this background that the high-level presence of the South African delegation, which included President Jacob Zuma, Minister of Public Service and Administration and APRM Focal Point Lindiwe Sisulu and Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Maite Nkoana-Mashabane should be welcomed.

As one of APRM’s architects, South Africa’s very public high profile engagement at the APRM Forum sends an important signal to other heads of state. Without participation at the highest level by all member states and robust discussions at the Forum, the APRM will continue to struggle to fulfil its potential.

Steven Gruzd and Yarik Turianskyi just returned from Addis Ababa, where they attended the African Union Summit and the APRM Forum opening session.