He has been condemned to life imprisonment by the judges of the Extraordinary African Chambers (EACs), a court specially created by Senegal upon the request of the African Union (AU). This was the first trial of its kind on the continent and years of lobbying were necessary to convince the AU and Senegal to proceed with it. In pushing Africa to bring Habré to justice, the victims and the international coalition of non-governmental organisations that have supported them have shown that Africa’s relationship to international criminal justice is far more open than the statements of some African leaders might suggest. Africa’s people demand such justice, and will pull all the necessary levers to obtain it.

The years that have passed seem to have reinforced the determination of the surviving victims, the victims’ families and the civil society organisations (CSOs) that have accompanied them – from the Chadian Association of Victims of Crimes and Political Repression (AVCRP) to the Chadian Association for the Promotion and Defence of Human Rights (ATPDH) to the Dakar-based based African Assembly for the Defence of Human Rights (RADDHO) to the international Human Rights Watch (HRW) and International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). In the absence of a straightforward legal path – it was evident from early on that the Chadian justice system would not request Habré’s extradition from Senegal to prosecute him, and the International Criminal Court’s (ICC)’s jurisdiction does not cover crimes committed before 2002 – they have, over the years, knocked on all doors. This has included calling on Senegalese justice, of course, but also on the UN Committee against Torture, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Belgium’s universal jurisdiction provisions, and the International Court of Justice, but also defending their case before the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), (of which Senegal is a member) that had been seized by Habré’s supporters and lawyers.

The campaign for the Habré trial has also successfully drawn on previous cases, and on the expertise that has now accumulated across the world on cases of mass human rights abuses. Argentinian forensics experts, with similar experience in their own country, were thus called upon to analyse Chad’s mass graves and testify in the trial. The courts’ name also naturally draws on the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, set up to try the surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime. It provided an initial legal template when Senegal was asked to create an ad hoc tribunal to try the former Chadian president.

The campaign, however, has not just been a legal one. In the absence of a guarantee that the trial would take place one day, the surviving victims have been keen to publish their testimonies. This has taken many forms, from the more traditional bibliographic account written by Souleymane Guengueng, to video testimonies gathered on HRW’s website or in documentary films such as Klaartje Quirijns’ The Dictator Hunter, Isabel Coixet’s Parler de Rose, or Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s Hissein Habre: a Chadian Tragedy. There are also written testimonies in civil society publications – in 2013 HRW published The Plain of the Dead, a 714-page account of the Habré repression system in great part based on victims’ testimonies – and interventions in the media. In so doing, the survivors have not only made sure their testimonies would be available beyond their own deaths, but also helped to publicise the Habré affair and gave it a very human face. Some of them have equally been present throughout the trial, delivering most of the witness testimonies in an attempt to represent as best as they could all victims, alive and dead.

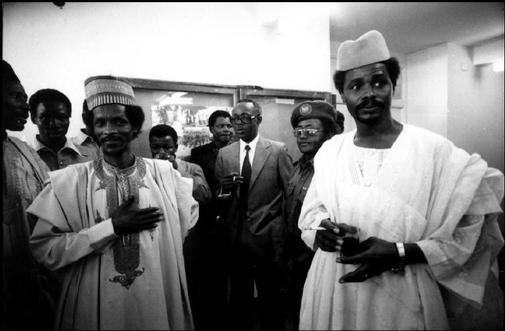

Chad’s Government of National Unity, headed by Goukouni Ooueddei (left), was created on 23 March 1979 in an attempt to end the civil war. Hissène Habré (right) was Minister of Defence until his loyalists overthrew the government in 1982, ushering in a military dictatorship that lasted until 1990. Photo (c) Ammagina, CC BY-SA 4.0

As with many such international justice prosecutions, Habré’s trial has taken place many thousands of kilometres away from most of his victims and the places where his secret police’s crimes took place. While some observers note that geographic distance, in some cases, may contribute to greater judicial serenity, most commentators state that it also means that justice remains out of reach for many victims and most of the population, and that the national judiciary is unable to strengthen its legitimacy in the eyes of the people. These are obvious shortcomings in the Habré affair, although the Chadian justice system prosecuted and condemned 20 Habré regime officials in 2015, in an obvious effort to show that justice could also be served in Chad.

Here, too, the steady involvement of the victims and CSOs has had an important effect on reducing the distance. They, and a number of initiatives launched by volunteers and legal professionals, have also made creative use of new technologies to promote the trial, record it and reach out to Chadians. Websites and Twitter have served as platforms to post regular updates on the proceedings while YouTube has hosted all trial recordings posted by the EACs’ interactive forum. Outreach activities in Chad are on-going and have notably included public screenings of extracts of the trial, and debates and dialogues with local inhabitants throughout the country.

Paradoxically, the victims’ long wait for a trial may well have increased the quality of the evidence presented before the EACs. It has had an obvious impact, first, on the quality of the documentary evidence used in the trial. The EAC investigators were thus able to use documents from the Direction de la documentation et de la sécurité (DDS), Habré’s political police, found by HRW investigators in 2001, as well as the testimonies gathered by CSOs and evidence collected by Belgian Judge Fransen, who investigated the case in 2001-2005 (at a time when it looked like Belgium, rather than Senegal, would prosecute Habré). Moreover, not only has the time elapsed had no adverse effect on the victims’ determination to testify, it may even have given them a greater freedom to do so. The trial thus uncovered a hitherto little-known aspect of Habré’s rule: the extent to which sexual violence was used by its repressive system (a crime now specifically acknowledged in the verdict although the EAC judges had initially refused to add it to the charges). This discovery was only possible thanks to the testimonies of a number of now middle-aged women who testified about the violence and abuses to which they were subjected with an incredible dignity and great clarity, looking Habré in the eye. It is not likely that they would have felt able, and free, to do so publicly twenty years ago, as younger women. The Habré trial has thus successfully overcome one of the main challenges in the prosecution of grave crimes, that of gathering enough high quality evidence and witness statements – something the ICC has been struggling to do, notably with regards to the Kenyan case.

In many ways, the Habré trial before the EACs and the campaign that led to it have underlined the importance of a multi-faceted approach in seeking international criminal justice. The victims and their allies have gone well beyond the obvious legal strategy to lobby the AU, Senegal and their international partners. In seeking the support of international civil society allies, drawing on existing international expertise, knocking on all institutional doors, using a wide range of media outlets, collecting, transcribing and storing evidence, and preparing for the trial and their witness statements, they have not only made sure that, in the words of one of Habré’s victims, Rose Lokissim, ‘Chad would thank [them] and History would remember [them]’, but that the long-awaited justice would be of the highest possible quality.

Marie Gibert is an associate lecturer at Birkbeck College, University of London.