What is holding back Africa’s development, and what’s being done about it? To what extent is corruption to blame, and is the continent’s 50-year development plan, Agenda 2063, up to the task of tackling it? The latest ‘Panama Papers’ revelations, released late July 2016, have implicated more African countries – 44 out of 54 countries on the continent use offshore financial structures.

According to Transparency International, in Liberia, seven out of ten people pay a bribe to access basic healthcare and education, and 75 million people in sub-Saharan Africa paid a bribe in 2015. Corruption literally takes from the mouths of the poor to enrich those in power.

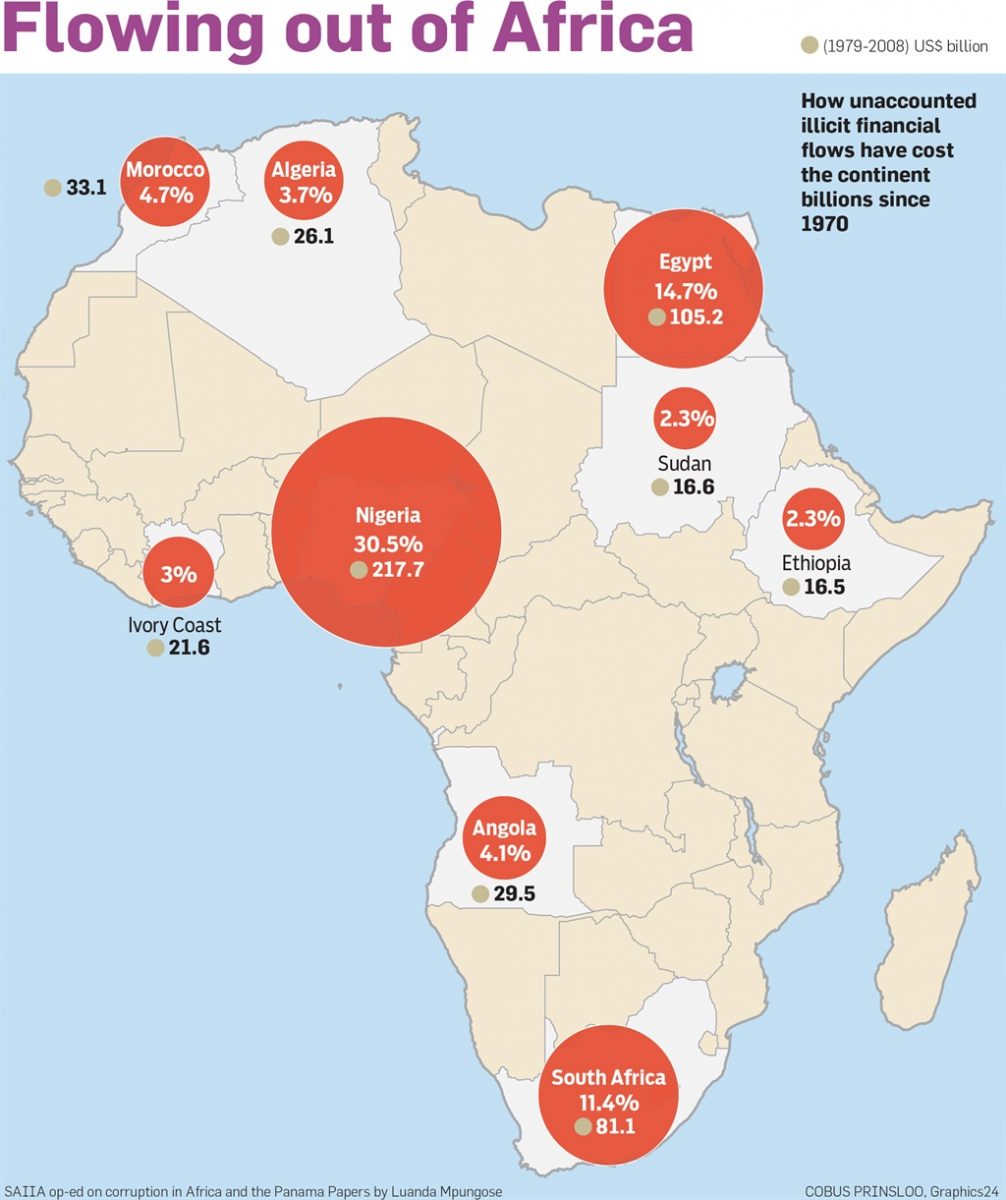

The recent report of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa on Illicit financial flows (IFFs), spearheaded by former South African President Thabo Mbeki, clearly illustrates just how corruption hamstrings Africa’s development. IFFs refer to money that is earned, used or transferred illegally. This can include commercial tax evasion, incorrect trade invoicing and abusive transfer pricing, criminal activities – drug trade, human trafficking, illegal arms dealing, and smuggling – and bribery and theft by corrupt government officials. According to the UN report, Africa is estimated to have lost in excess of one trillion dollars in IFFs over the last 50 years.

Infographic © City Press

Likewise, the Panama Papers uncovered how billions have left the continent in questionable circumstances. Thousands of documents leaked from the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca expose companies and individuals who hold shell companies and offshore accounts in order to evade tax and sanctions or to conduct corrupt business. Although offshore accounts are not always used for illegitimate or criminal purposes, corrupt companies and people tend to take advantage of these anonymous company structures. These leaks have implicated a number of influential, politically connected Africans, including Khulubuse Zuma, nephew of South Africa’s president, former Niger Delta Governor James Ibori who is serving time in prison, and Jaynet Kabila, sister to Democratic Republic of Congo President Joseph Kabila, to name a few.

For example, an estimated $217.7 billion dollars reportedly left Nigeria illegitimately between 1970 and 2008. Transparency International suggests that corrupt behaviour in the form of nepotism, cronyism, and preservation of power are embedded within the country’s social norms. Academics Wale Adebanwi and Ebenezer Obadare describe Nigeria as a prebendalist state in which power, in previous years, has been maintained through granting of personal favours and the use of public office for personal gain. The African Peer Review Mechanism Country Review Report on Nigeria also highlights that ‘corruption is endemic at all levels of society and has been described as a way of life in Nigeria.’

Former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, infamously referred to Nigeria and Afghanistan as ‘fantastically corrupt countries’ ahead of the Anti-Corruption Summit held in London on 12 May 2016. But money that leaves the continent illicitly ultimately ends up somewhere else, and this casts aspersions on the role of the international community in combatting corruption. For example, some Western countries and so-called tax havens make it possible for companies and individuals to perpetuate corrupt deeds by allowing registration of shell companies or purchasing of property without insisting on beneficiary ownership registration. A key take-away from the Anti-Corruption Summit was the participants’ pledge to ‘end the misuse of anonymous companies to hide the proceeds of corruption’ as reported by The Economist.

What are the prospects of an Anti-Corruption Summit in Africa, by the AU and African governments? Prevailing realities demand more action at domestic levels. Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari has been recognised as a warrior against corruption. Since taking office in May 2015, he has fired senior officials from the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, arguably the country’s most corrupt industry. Nigeria’s finance ministry removed more than 23,000 non-existent workers from the national payroll, after a biometric investigation, saving $82 million a month. This should create a precedent for African countries to follow. In an effort to find a solution to IFFs, South African Finance minister Pravin Gordon called for reinforcement of the law against IFFs, at a high-level conference in Pretoria in July 2016.

Agenda 2063 – the African Union’s visionary document for what the continent will look like in 50 years’ time – aspires for a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development in which the African people have a high standard of living, good quality of life, and sound health and well-being. Corruption undermines this vision, and creates and increases poverty and exclusion. However, the Agenda contains very little mention of anti-corruption plans and action and no clear strategy as to how this will be achieved or driven, which builds scepticism about the realisation of the Agenda. The call for action is generally too ambitious. For example, it aspires to ‘silence the guns’ in Africa by 2020 – an extremely unlikely prospect in the next four years.

The IFF report and the Panama Paper leaks indicate the staggering amounts that have left the continent illegally, retarding development objectives. Governments should prioritise transparency and accountability. There needs to be a more rigorous and robust strategy and practical steps from the AU, coupled with strong political will from its member states, to move towards the prosperous and developed Africa that Agenda 2063 envisions. A good starting point is for every African government to sign up to and support the Global Declaration against corruption, adopted at this year’s Anti-Corruption Summit.

This article was first published in the City Press print edition on the 28 August 2016. The image above was provided by City Press.