A few months ago I travelled to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia and headquarters of the African Union. I have been traveling to this beautiful country about twice a year for the past decade. What struck me and prompted this reflection on African integration was noticing that in the past few years restrictions on entry have become increasingly harsher. One is tempted to ask questions about the dream of free movement of citizens across Africa – and therefore continental integration and unity.

First, visas are required, and travellers are instructed to acquire these at Ethiopian diplomatic or consular missions in their home country. I am not sure how many such facilities are available across the continent, but the “capital of Africa” is not represented in all 53 countries. So the alternative is to arrange a visa in a neighbouring country with an Ethiopian mission or arrange to receive it on entry. Only two neighbouring countries’ citizens require no visas (Ethiopia has six neighbours).

Second, the visas are paid for in American (US) dollars – and ostensibly no other currency – not even Ethiopian Birr. Third, according to what I assume are official information documents, citizens of 18 countries around the world qualify to receive visas upon arrival in Ethiopia. Out of these, only one is African: South Africa. All other Africans need a visa paid for in US dollars and secured before they leave their countries – unless a special arrangement has been made and approved by immigration authorities at the port of entry.

Fourth, only four currencies are exchangeable in Ethiopian banks. Here again only one African currency is a member of this exclusive club: the Birr. This is in contrast to my first trip to Addis a decade ago, when South African Rand was also accepted.

In practice, therefore, only Kenyans, Somalis and South Africans can travel to Ethiopia without the hindrance of a cumbersome and expensive visa regime.

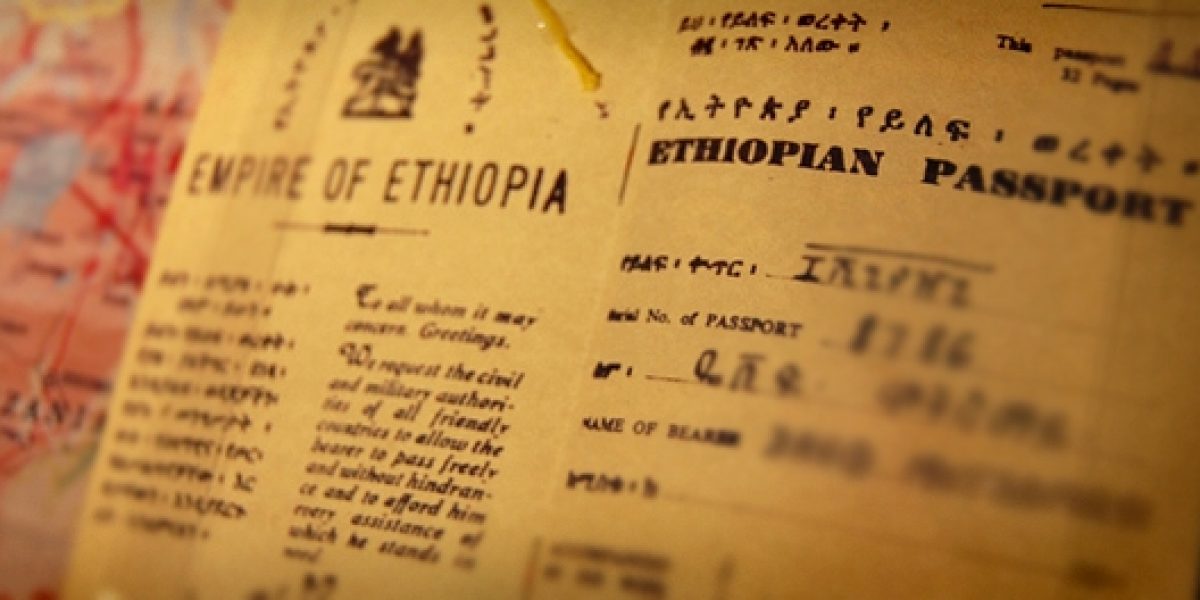

Now, what do these arrangements mean for integrating Africa through economic relations and free human movement? This is not an odd question. Addis Ababa has for 50 years been the diplomatic and political capital of Africa, where the AU, UNECA, diplomatic missions and other agencies that serve the continent are located; and where at least once a year our leaders congregate to plot African unity and integration – the dream of a united, integrated and internally coherent continent.

While the strategies for integration adopted by the AU under various projects (the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), Lagos Plan of Action, AU Constitutive Act and African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) among them) are to be gradual and based on regionally operational economic units (like the economic communities of Southern Africa (SADC), East Africa (EAC) and West Africa (ECOWAS)), the ultimate goal envisages these culminating in an African Economic Community and Central Bank. It therefore stands to reason that Addis Ababa, as the centre of these initiatives and the ultimate Brussels or Washington equivalent of a “United States of Africa” would lead by example and open its doors to the continent’s citizens equally and affordably.

But alas! This is not the case, and increasingly African citizens are subjected to restrictions that, in their operation, negate the concept of this beautiful city as the home to all. So, are our leaders really serious about facilitating the integration of the continent, or is it just rhetorical shadow-boxing?

If they were serious, surely they should press Ethiopian authorities – understandably concerned with security, human and drug-trafficking, and so forth – to facilitate easier, cheaper and friendlier movement of people; and should further insist that African currencies, despite their weaknesses, be more easily exchangeable within the Ethiopian system.

This would be a start, and would show commitment to real integration, laying the basis for realising the dream of the founding fathers of the Organisation of African Unity 50 years ago.

But lest we forget, our leaders themselves do not experience these inconveniences when they go to Addis. They get whisked from their airplanes straight to their hotels by diplomatic minions, bypassing the red tape, and pay for their stays with our monies already conveniently converted into non-African currencies without the hassle and embarrassment of having their national currencies rejected by local banks.

Of course, these challenges do not apply only in Addis Ababa, but also in many other capitals. But the point here is that unlike Lilongwe, Maseru and Nouakchott, Addis Ababa is a flagship of African unity and integration. Therefore the failure of Ethiopians and Africans to correct the image of this city as African-unfriendly can only harm the aspirations of a continent to be united, strong and prosperous in the next 50 years – despite the plethora of initiatives by the AU aimed at this.

African integration deferred indeed!