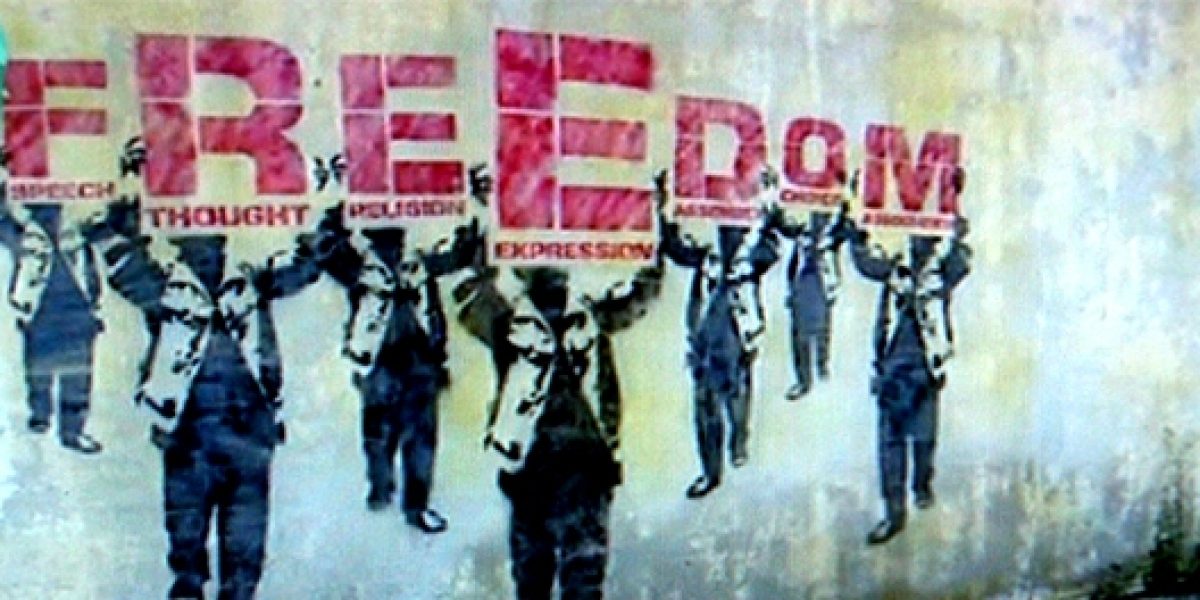

It speaks directly to the ideal of human and civic freedom. For many people in South Africa and the continent at large, this is intimately linked to conceptions of democracy.

Scholar and journalist Dr Fareed Zakaria has argued that if electoral democracy is to be a meaningful instrument for enhancing citizens’ freedom, electoral competition must be underwritten by civil liberties – the right to express views, form associations and so on. When respected, civil liberties help foster a culture in which competition and diversity are normal and positive aspects of societal life. Developing a robust regime of civil liberties is a precondition for robust democracy.

How is Africa faring?

The continental picture of civil liberties is mixed. Freedoms of expression, of association and of religion – to name a few – are protected by various human rights conventions and national constitutions. These guarantees are important both as protections for citizens’ freedom (an end in itself) and as pillars of democratic dispensations. It is difficult to imagine a fair election taking place when people are prohibited from discussing issues, advancing alternative perspectives on them, or persuading others about their viewpoints.

But truly open environments are few, confined mostly to the continent’s more aggressive democratisers, such as Benin and Ghana. Media are generally able to run the stories they choose. Political parties abound. Perhaps most importantly, civil society organisations (CSOs) have seized available space to organise and advocate for their causes. Sometimes, as in the case of the Treatment Action Campaign’s activism around the provision of treatment to people living with HIV in South Africa, they exercise profound influence on policy.

Read the full report: Building Freedom? Securing Constitutionalism and Civil Liberties in Africa: An Analysis of Evidence from the APRM

More common are hybridised circumstances where varying degrees of freedom (perhaps legally guaranteed, and representing greater openness than existed in decades past) coexist with legal or practical restrictions. Thus, while Mozambique embraces multi-partyism, widespread conflation of ruling party and state makes life difficult for opposition sympathisers. In Zambia and Nigeria, mobilised civil societies helped defeat attempts by incumbent presidents to extend their tenures – but official suspicion and occasional harassment (from various quarters) complicates CSOs’ work.

In more extreme cases, civil liberties are deliberately restricted in the name of security and communal harmony. Ethiopia’s 2009 Charities and Societies Proclamation imposes stiff restrictions on civil society groups working in fields like governance and human rights: such groups must raise 90% of their income locally, which is prohibitively hard to do. Unsurprisingly, in such environments, opposition groups are sceptical of the very probity of elections.

What does this imply for the continent’s future? According to Thomas Carothers of the Carnegie Foundation for International Peace, what is emerging may not be a halfway house to a ‘normal’ democracy, characterised by the choices of free and autonomous citizens. Rather, it may represent a distinct form of democracy – ‘illiberal democracy’ or ‘competitive autocracy’ – electoral choice within constrained societal environments.

Globally, the pull of freedom has waned, largely due to the apparently successful example of authoritarian development in China and elsewhere in the East. In Africa, voices have arisen arguing that extensive liberties are incompatible with African culture and cannot be afforded in view of the continent’s developmental deficits and need for stability. Indeed, this is the argument that Rwanda’s leadership has made, stressing the danger of regression into genocidal ethnic conflict.

An active pushback by governments against some of the spaces that citizens and activists have occupied is an attractive prospect to them. A knowledgeable source on Ethiopian politics said that its legislation has prompted interest elsewhere in Africa: ‘The Charities and Societies Proclamation and other associated ones like the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation and the Revised Election Guidelines are quite prohibitive by all international human rights standards, but hold attraction to many repressive regimes on the continent. I am informed that some 20 on the continent have started to digest the CSP, in particular.’

If Africa’s democrats aspire to a future in which democracy encompasses individual and societal freedom, they will need to gird themselves for a hard campaign to consolidate a robust regime of civil liberties. This demands ongoing intellectual engagement – making arguments about the importance of civil liberties – and being prepared to challenge powerful interests that would prefer to see them muzzled.

The quality of democracy, and whether it means freedom, ultimately, will proceed from the choices and actions of Africa’s citizens.