Recommendations:

- The government of Mozambique should take control of its porous borders. The unregulated flow of foreigners across its border with Tanzania has helped to marginalise local communities in Cabo Delgado. Bolstering porous land and maritime borders in Cabo Delgado would reduce this illegal immigration, which contributes to local unemployment and radicalisation by foreign militants.

- The government of Mozambique and international investors should provide better employment opportunities for youths in Cabo Delgado. Prioritising their recruitment in local companies and using revenues from multinationals to build local development, especially in fisheries and mining, would help lessen the appeal of radicalism.

- The government of Mozambique and the international community should strengthen the capabilities of the Mozambican army. With poorly trained, ill-equipped and under-paid troops, the ability to conduct complex missions against insurgents is compromised from the outset. Investment and training are crucial.

Executive summary

The crisis in Cabo Delgado, while cast in terms of the incendiary rhetoric of armed religious extremism, has its origins in the systemic neglect and regional inequalities that plague this ‘forgotten’ province in northern Mozambique. The onset of a resource scramble has seen an influx of economic migrants and spurred rent-seeking by the elite with multinationals. As a result, local communities have become even further marginalised. In this context, Mozambique’s self-styled ‘al-Shabaab’ – and the government’s inept security crackdown in response to these attacks – is further seeding the ground for localised grievances to deepen into long-term structural problems.

Introduction

The outbreak of unrest in the remote Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado in October 2017 captured media attention when perpetrators claimed links with the Islamic State (ISIS). The Mozambican government’s assertion that these scattered acts of violence were evidence of militant Islam, which included the ‘calling card’ of Islamist terrorists – beheadings – whipped up international fears of a new ISIS-like front in Africa. Closer examination cast doubt on this initial interpretation of the ‘insurgency’, but the sheer tenacity of young men wreaking violence in the small provincial towns and their seemingly unrepentant brandishing of the symbols of Islamist militancy suggest otherwise.

Although the insurgency may seem to external observers and even many Mozambicans in the capital far to the south to have sprung out of nowhere, the conditions for rebellion have been present for some time now. Unemployment is endemic across the region and worsened by the devastating effects of natural disasters in recent years. The discovery of precious gemstones and offshore natural gas deposits 10 years ago raised expectations that these revenues would help local communities; in fact, this set off a brutal resource scramble pitting national elites, artisanal miners and local farmers against one another. Cycles of destruction and bloodshed perpetrated by Islamist militants and countered by police and security forces have been exacerbating this situation since 2017, rendering parts of the province ungovernable. In short, there is little tangible evidence of the positive impact of resource-led growth on local communities’ livelihoods. Coupled with the destruction wrought by Islamist insurgents, the situation threatens the viability of those same communities, broader commercial interests and ultimately political stability in the region. These conditions, similar to those found in the Sahel, are fertile ground for recruitment to the militant cause.

This policy briefing argues that the crisis in Cabo Delgado, while cast in terms of the rhetoric of armed religious extremism, has its origins in the systemic neglect of this ‘forgotten’ northern part of the country. The resource scramble has seen an influx of economic migrants, encouraged elite rent-seeking with multinationals and as a consequence further marginalised local communities. In this context, Mozambique’s own ‘al-Shabaab’ and the government’s inept security crackdown are turning localised grievances into long-term structural problems.

Cabo Delgado – promise, neglect and exploitation

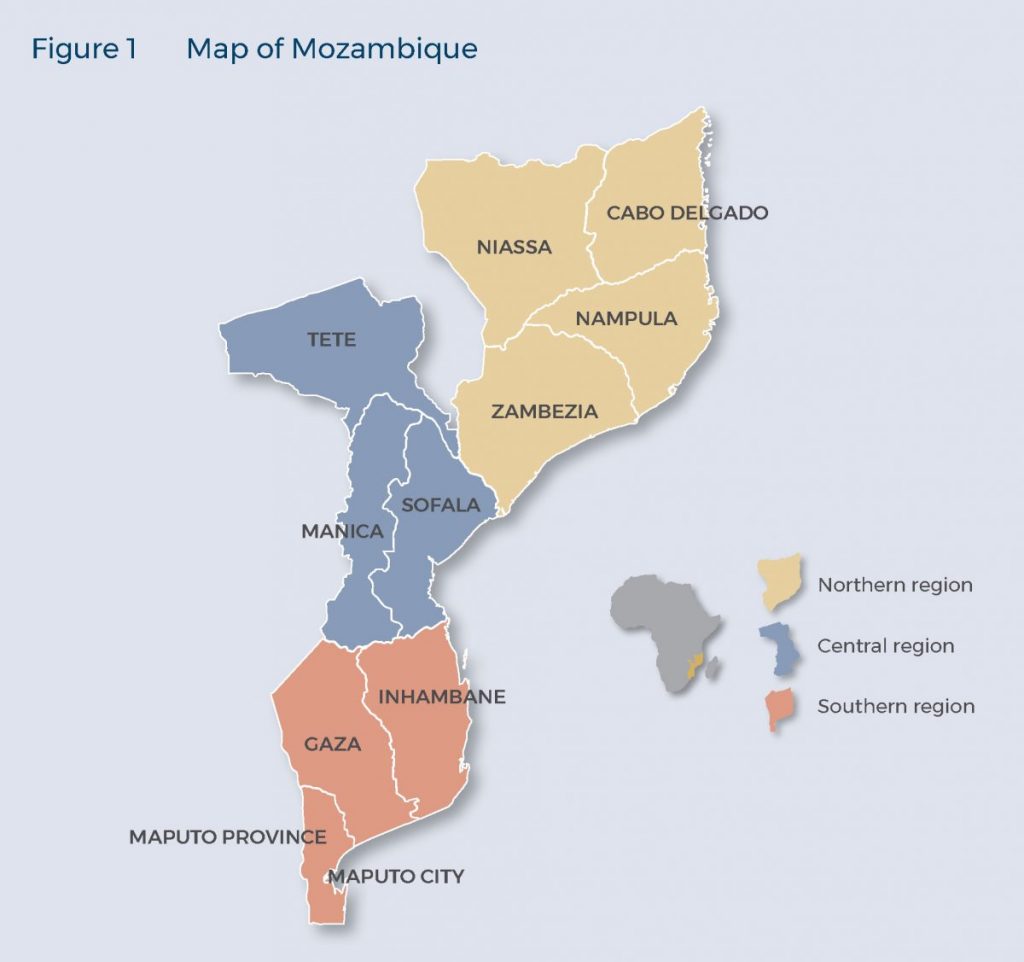

Situated on the northernmost portion of Mozambique’s long seaboard, the province of Cabo Delgado has been shaped by Indian Ocean trading networks dating back to the ninth century and, with these, the spread of Islam along what became known as the Swahili coast.1See Edward Alpers, East Africa and the Indian Ocean (Princeton: Markus Wiener, 2009).Under Portuguese suzerainty from the 16th century onwards, Cabo Delgado earned an iconic role in the anti-colonial struggle as the Makonde people in the province’s Mueda plateau formed the backbone of Frelimo’s guerrillas in the 1960s.2See Martin Newitt, A History of Mozambique (London: Hurst, 1995).Independence in 1975 did not, however, bring the expected economic improvements and its overwhelmingly rural population was caught up in the civil war between the Frelimo government and Renamo insurgents until the peace settlement of 1992. Despite supporting Frelimo in national elections from 1994 onwards, the province did not experience the economic growth, per capita income surge and investment boom felt in Maputo and surrounds in the southern part of the country either.3UN Development Programme, Gender, Women and HD: An Agenda for the Future, 2013, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/ mozambique_2001_en.pdf.Even the election of the country’s first president of Makonde origin, Filipe Nyusi, in 2014 did not bring about any visible change.

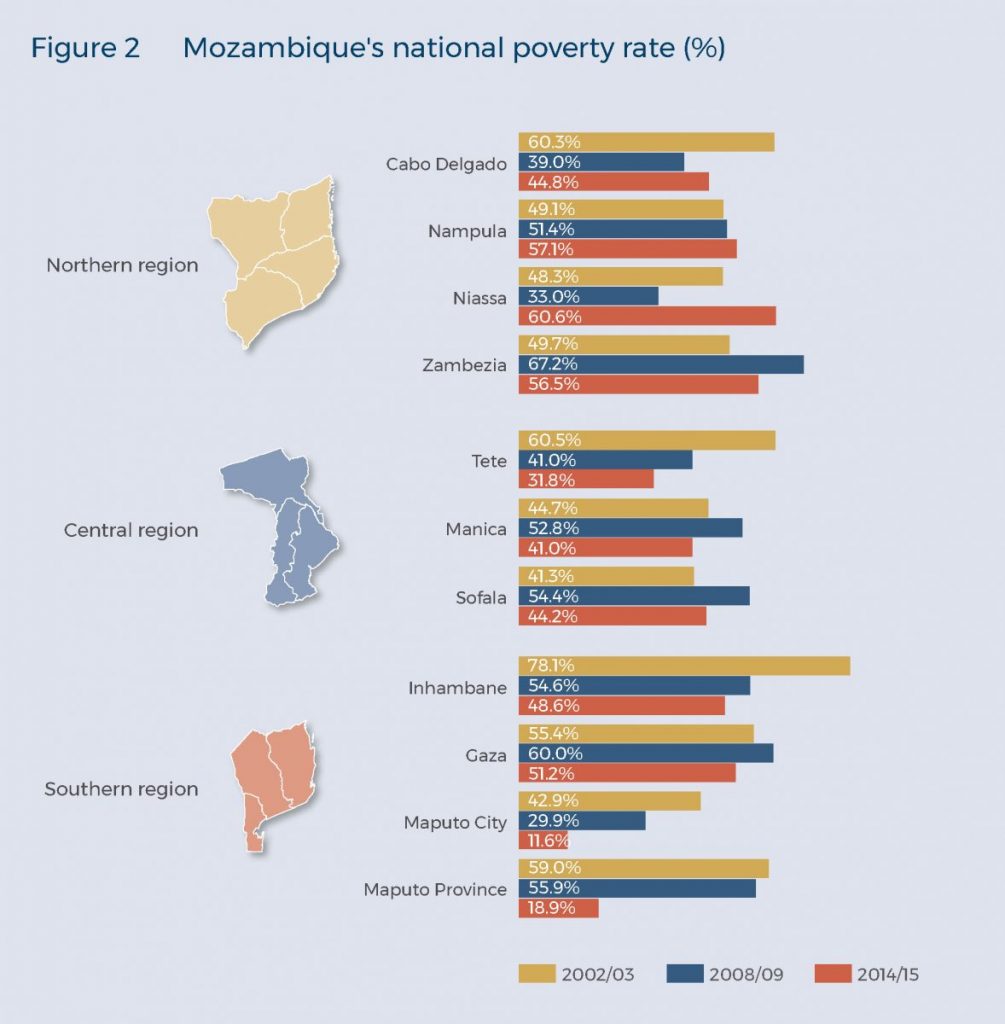

Poverty is rife, with Cabo Delgado the second poorest of Mozambique’s provinces.4Jerry Maquenzi and João Feijó, “Pobreza, Desigualdades e Conflitos no Norte de Cabo Delgado” (Poverty, Inequalities and Conflicts in North Cabo Delgado), Observador Rural – Documento de Trabalho 76 (July 2019): 4–6, https://clubofmozambique.com/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/OR-76-Conflitualidade-em-Cabo-Delgado.pdf.With subsistence agriculture the primary source of income for the vast majority of the population and few opportunities outside of this sector, non-farming activity tends to centre on resource exploitation. Forestry products, from legal and illegal logging, are exported with the collusion of local Frelimo officials.5Environmental Investigation Agency, First Class Connections: Log Smuggling, Illegal Logging and Corruption in Mozambique (London: EIA, 2013), 1–16.Precious gems, particularly high-quality rubies, have been mined in the Montepuez district by garimpeiros (artisanal miners) since 2009. Their gradual sidelining through a joint venture between the mining company of the former Frelimo governor of Cabo Delgado and a subsidiary of Gemfields in 2012 has led to the dislocation of hundreds of local families and the ejection of foreign garimpeiros (many of whom are Tanzanians).6Estácio Valoi, “The Blood Rubies of Montepuez”, Foreign Policy, May 3, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/03/the-blood-rubiesof-montepuez-mozambique-gemfields-illegal-mining/.In 2017, a few months before the first attack in Mocímboa da Praia, a brutal campaign perpetrated by a machete-wielding militia began against those locals who refused to leave their land, which was being claimed by the mining company. Adding to the woes of garimpeiros were corrupt police who regularly robbed them of their finds.7Sérgio Chichava, “Who Is the Enemy Attacking Cabo Delgado? Short Presentation of the Hypotheses of the Mozambican Government”, IDeIAS 127 (April 28, 2020), https://www.iese.ac.mz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ideias-127e_SC.pdf; Sérgio Chichava, “Did Frelimo Create ‘Al Shabaab’? An Analysis of the 15 October 2019 Elections from Cabo Delgado” (forthcoming).

At the same time there is a growing trade in wildlife products, particularly ivory, pangolin and, on the coast, marine life. After provincial police tasked with stopping illegal logging and poaching were redeployed to protect ruby mines, a small but growing contingent of locals began working with criminal networks to exploit resources for export to Asian markets. Linked to some of these trading networks are coastal dhows transporting heroin from Pakistan and Afghanistan via Mozambique to European markets.8Simone Haysom, Peter Gastrow and Mark Shaw, “The Heroin Coast: A Political Economy Along the Eastern African Seaboard” (Research Paper 4, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, Geneva, June 2018), https://globalinitiative.net/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/2018-06-27-research-paper-heroin-coast-pdf.pdf.

Tourism – a sector that could employ a vast pool of semi-skilled local labour – saw some promising developments in this period. The establishment of the Quirimbas National Park and the Niassa National Reserve in the neighbouring province, alongside private initiatives in Pemba and further up the coast, had begun to attract a steady stream of tourists. However, they have been driven away by the rampant poaching and insecurity. Even natural disasters have played their part, with successive cyclones in 2019 wreaking havoc on the fragile infrastructure of towns and villages in Cabo Delgado well into the interior.9UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “Cyclones Idai and Kenneth”, https://www.unocha.org/southern-andeastern-africa-rosea/cyclones-idai-and-kenneth.Displaced people, numbering over 100 000, found themselves unable to conduct even a subsidence existence.

The discovery of offshore natural gas deposits in 2010 promised unprecedented prosperity to the neglected region and significant revenues to the national government. While local expectations ran high, the realities of exploitation and a surge in internal migrants hoping to benefit from the hydrocarbon boom put paid to these.10João Feijó (Researcher, Rural Observatory), quoted in Club of Mozambique, “Cabo Delgado: Study Points to Poverty as Cause of Armed Attacks”, July 26, 2019, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/cabo-delgado-study-points-to-poverty-as-cause-of-armedattacks-137869/.Local communities were, as in the case of the ruby mines, ignored. This was particularly the case with the already marginalised Mwani people. Suspicions of corruption by top officials in the ruling party fuelled local discontent, as noted in one study, at a time when incomes in northern Mozambique were falling systematically.11Maquenzi and Feijó, “Pobreza, Desigualdades e Conflitos”.International multinationals, including Anadarko and ENI, introduced employment opportunities as part of their infrastructure projects, but these fell far short of the needs and expectations of locals.

Al-Shabaab

That religious ideas traverse Swahili coastal communities, articulated by community leaders, peddled by aspirants and reflected in the judgements of local qadis, is nothing new. Conceptions of modernity, Arab nationalism and traditionalism have all historically jostled for position in these syncretic trading societies.12See, for example, Nathaniel Mathews, “Imagining Arab Communities: Colonialism, Islamic Reform and Arab Identity in Mombasa, Kenya, 1897–1933”, Islamic Africa 4, no. 2 (2013): 135–163.It was in this fertile milieu that Mozambique’s ‘al-Shabaab’ emerged, linked to radical Kenyan cleric Aboud Rogo Mohammed and his followers, whose assassination on 27 August 2012 inspired days of rioting in Mombasa.

Ansar al-Sunna or Ahlu Sunna Wal Jammaa (loosely translated as ‘people of the Sunna community’) is the name formally used by Islamist militants operating in northern Mozambique. Their origins are tied to what some locals think was a sect operating in Cabo Delgado since 2015 if not earlier, also said to be influenced by Rogo.13Sérgio Chichava, “The First Signs of ‘Al Shabaab’ in Cabo Delgado: Some Stories from Macomia and Ancuabe”, IDeIAS 129 (May 8, 2020), https://www.iese.ac.mz/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ideias-129e_SC.pdf; Eric Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, Nature and Beginning”, Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 3 (2020): 396–412.Within Cabo Delgado, disputes with local Muslim bodies and law officials, which opposed the sect’s efforts to impose strict interpretations of sharia law in towns, resulted in increasingly violent clashes and the arrest of sect members.14Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency”, 404–405.Although it is a matter of dispute, the crackdown by Tanzanian police on Rogo’s followers in Mtwara (just north of the Mozambican border) in early 2017 generated over 100 arrests.15Jules Duhamel, Twitter, @julesdhl, March 3, 2019; see also ACAPS, “Mozambique”, https://www.acaps.org/country/mozambique/ crisis/violent-insurgency-in-cabo-delgado.It is believed that some of the Tanzanians who escaped arrest by crossing into Mozambique joined up with ‘al-Shabaab’, as did Ugandans after a similar police operation targeting the Usafi Mosque in Kampala.16Andrew Bagala, “Police Want Usafi Mosque Imam, Five Others Extradited”, Daily Monitor, January 30, 2019, https://www.monitor. co.ug/News/National/Police-Usafi-mosque-imam-five-extradited-Mozambique/688334-4957372-sb7ajhz/index.html; see also Sérgio Chichava, “Ugandenses e Tanzanianos do ‘Al Shabaab’: Um Olhar à Dimensão Internacional do Conflito em Cabo Delgado”(Ugandans and Tanzanians of Al Shabaab: An Analysis of the International Dimension of the Conflict in Cabo Delgado), in Desafios Para Mocambique 2020, ed. Salvador Forquilha (Maputo: IESE, forthcoming).Former garimpeiros from Tanzania were also found to be among the ‘al-Shabaab’ adherents.

On 5 October 2017, 30 armed insurgents attacked three police stations in the border town of Mocímboa da Praia. During the following year, 50 more attacks on police stations and other government offices occurred in northern districts. Most notably, on 22 February 2019 Islamist insurgents opened up a new front when they attacked a convoy of employees from Anadarko near Palma, the headquarters of the offshore natural gas project. All in all, 1 100 deaths have been attributed to the onset of insurgency since October 2017, with many civilians caught up in the crossfire.17Andrea Carboni, “CDT: Spotlight Escalation in Mozambique”, ACLED, April 30, 2020, https://acleddata.com/2020/04/30/cdt-spot light-escalation-in-mozambique/.

The pattern of destruction by the Islamist insurgents since the outbreak of violence in October 2017 focuses on government buildings, including district offices, schools and health clinics. For instance, the targeting of government health clinics in the province has forced 37 out of 130 to close (or be abandoned) in the districts of Mocímboa da Praia, Quissanga, Meluco and Macomia, leaving 750 000 Mozambicans without access to public healthcare facilities.18ACAPS, “Mozambique: Violent Insurgency in Cabo Delgado”, July 16, 2020, https://www.acaps.org/country/mozambique/crisis/ violent-insurgency-in-cabo-delgado.During the 2019 elections attacks disrupted voter registration and voting in Cabo Delgado province, particularly in parts of Mocímboa da Praia, Palma, Macomia and Meluco districts. According to Mozambique’s National Election Commission, 10 polling stations were unable to open because of the conflict, preventing 5 400 people from voting in in Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia and Muidumbe districts, out of a total of 1 185 024 registered voters in the province. Similarly, the election campaigns of political parties were concentrated in district capitals and carried out under military escort.19Chichava, “Did Frelimo Create ‘Al Shabaab’?”.

Estimates of the number of insurgents vary considerably, with some suggesting that there is a core of 200 members while others believe it to be four times that number.20Yonas Dembele, Mozambique: Islamic Insurgency – In-Depth Analysis of Ahl Sunnah wa al-Jama’ah (ASWJ) (Johannesburg: Open Doors, World Watch Research, July 2020), 7. Evidence suggests that members are partially recruited through offers of money and credit, with those who default being executed by beheading.21Joseph Hanlon, “ Islamists Recruited by Filling the Development Gap with Jobs and Loans – but Some Beheaded for Defaulting”, Mozambique News, December 10, 2018.To date, they have refrained from the usual publicity tactic of issuing statements after violent attacks, lending them an air of mystery and creating confusion about their purpose. However, social media sources in ‘alShabaab’ claimed that these actions were taken as part of their operations, a point vividly made during the temporary occupation of Mocímboa da Praia and Quissanga on 23–24 March 2020 when insurgents hoisted the black ISIS flag.22“Mozambique: Is Cabo Delgado the Latest Islamic State Outpost?”, BBC News, May 5, 2020, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/worldafrica-52532741.

Police and government security forces already present in Montepuez and engaged in the protection of commercial interests – and the forcible removal of local farmers and artisanal miners – have moved into the area.23Valoi, “The Blood Rubies of Montepuez”.Despite numerous skirmishes with militants, these security forces have not been able to stamp out the mobile insurgency. Legal and quasilegal tools such as detentions and disappearances were used as security forces swept across the coastal region.24Human Rights Watch, “Mozambique: Events of 2018”, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/mozambique.Yet decades of neglect and a dearth of investment in the armed forces after the end of the civil war in 1992 have left it without the capacity to conduct relatively complex operations.25As Hanlon pointed out in 2010, since the end of the war Mozambique “has only maintained a small and largely ineffective army and tiny military budget”. See J Hanlon, “Mozambique: ‘The War Ended 17 Years Ago, but We Are Still Poor’”, Conflict, Security & Development 10, no. 1 (2010): 77–102. In 2013 Defense Web stated that most Mozambican army equipment was unserviceable and that its air force and navy were in a poor state.In addition, Mozambique’s armed forces have to deal with a persistent leakage of information by unmotivated soldiers about logistics, conditions on the ground and wages. It is even believed they have been infiltrated by radical elements cooperating with the insurgency.

After the attack on Anadarko in February 2019 multinational firms contracted private security firms to protect their employees and interests. However, the Russian security firm, the Wagner Group, fled after an attack in March and alleged ongoing disputes with the Mozambican military. It was replaced by a South African security firm, Dyck Group, which was able to inflict casualties on the insurgents in early April 2020.

Conclusion: Another ‘Niger Delta’ in the making?

According to geologists, the Rovuma Delta basin and surrounds share some of the geological features found in the Niger Delta that created the conditions for hydrocarbon deposits.26Estevão Stefane Mahanjane and Dieter Frank, “The Rovuma Delta Deep-Water Fold-And-Thrust Belt, Offshore Mozambique”, Techtonophysics 614 ( 2013): 14–16, DOI: 10.1016/j.tecto.2013.12.017.Tragically, these formative tectonic forces are finding their contemporary political parallel in a government seemingly intent on reproducing the policy failings of successive Nigerian governments. The Niger Delta, an oil-rich region in Nigeria that serves as the country’s cash cow, is notorious for state neglect that has led to decades of civil strife, grinding poverty and environmental degradation.27See Uwafiokun Idemudia, “The Changing Phases of the Niger Delta Conflict: Implications for Conflict Escalation and the Return to Peace”, Conflict, Security and Development 9, no. 3 (2009): 307–331.Frelimo, once a bastion of revolutionary idealism and collectivist distributive policies, seems to struggle to find the means and the will to address the underlying causes and stem the tide of militant discontent in the province.

Although the crisis in Cabo Delgado threatens to spill over into neighbouring provinces and states, the expected response across the region has been surprisingly muted until very recently.28Tonderayi Mukeredzi, “Mozambique’s Insurgency Is a Regional Problem”, Foreign Policy, July 1, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/20 20/07/01/mozambique-islamist-insurgency-regional-problem-cabo-delgado/.The usual architects of intervention in Mozambique – Zimbabwe and South Africa – are preoccupied with their own domestic crises. In the case of Zimbabwe, the wheels of the post-Mugabe era are coming off and exposing President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s venal intentions, while South Africa is under renewed pressure owing to economic hardship and factional strife in the ruling African National Congress. Tanzania’s interests in the Rovuma Delta basin, both directly in the offshore hydrocarbons and through the proximity of its mobile Swahili communities, are more likely to play a key role in addressing instability. Yet it too has been slow to act, arguably because of the violent expulsion of its citizens from Montepuez. It only recently deployed its troops on the border to curb any spillover. Notably, even the Mozambican Ministry of Justice lacks faith in Cabo Delgado’s provincial police to hold on to wanted criminals, a candid admission of the collapse of national authority.29Oxpeckers, “East Africa’s Ivory Smuggled Out of Mozambican Ports”, 2017, https://oxpeckers.org/2017/11/ivory-smugglers/.

Since June 2020, however, regional indifference seems to be changing and there are apparently discussions of a coordinated intervention by SADC.30Institute for Security Studies, “Mozambique Insurgency Requires Urgent Response from SADC and AU”, Press Release, August 13, 2020, https://issafrica.org/about-us/press-releases/mozambique-insurgency-requires-urgent-response-from-sadc-and-the-au; Theo Neethling, “Why South Africa Has a Keen Interest in Extremist Violence in Northern Mozambique”, The Conversation, June 22, 2020, https://theconversation.com/why-south-africa-has-a-keen-interest-in-extremist-violence-in-northern-mozambique-140745.Yet, without coordinated policing, a fair justice system and a penal system that incarcerates criminals no matter how politically connected, it is hard to see how the insurgency is to be addressed in any meaningful way.31Amabélia Chuquela (Mozambican Deputy Attorney General), quoted in Club of Mozambique, “Cabo Delgado”.Dealing with structural inequalities in Cabo Delgado, helping damaged local communities and transforming regional economic opportunities into improved livelihoods are the only viable long-term solutions to a conflict that never should have happened.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Konrand Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) for this publication