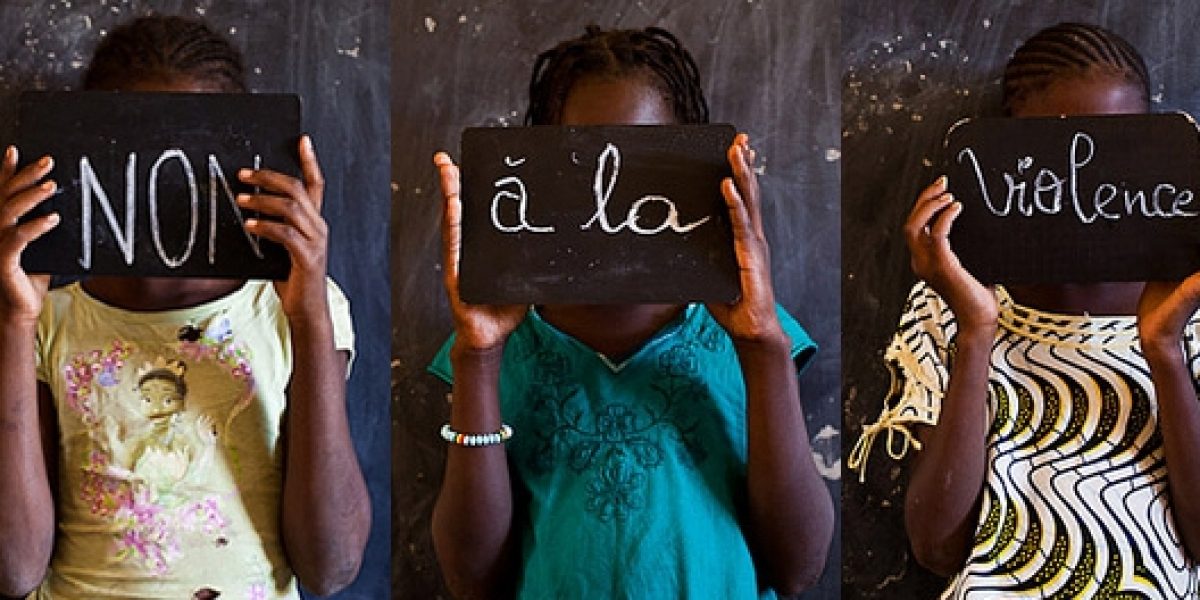

These and various related terms have been bandied around for decades in the quest for gender justice and freedom from gender inequality, biases and stereotypes, as well as the unequal power relations that often come with the status of being born a woman in Africa.

These concerns have long preoccupied African human rights and gender activists, civil society, scholars, policy makers and implementers, spawning many strategies, action plans, policies, laws and programmes in a bid to end or at least reduce the many forms of violence against Africa’s women.

The African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) – Africa’s home-grown governance assessment tool – gives due prominence in principle, form and content to the rights of women in Africa and specifically on the need to combat violence against women, as reflected in its objectives, and in the Country Review Reports and the APRM Implementation Reports of the reviewed countries.

Click here to visit SAIIA’s APRM Toolkit, a comprehensive repository of APRM knowledge for continental practitioners, civil society members, academics, students, journalists and donors.

While gender-based violence concepts are now commonplace in mainstream human rights discourse, for victims and survivors of violence, they must seem like empty rhetoric; little has changed in reality. African women face daily threats and actual harm to their person on a scale that in times of war would evoke outcries of crimes against humanity. The 2015 UN Women Beijing +20 Report points to Africa as having the highest prevalence of physical or sexual intimate partner violence at 45.6% in low- to middle-income countries.

The APRM Country Review Report of South Africa (2007), in pointing out that women faced abuse in the sexual, economic and psychological arena, noted that one in two women is raped in her life. It also noted that there are 150 rapes per day, that one in four women are in an abusive relationship, that 85% of rapes are gang rapes and that a woman is killed every six days by an intimate partner. The SADC Gender Protocol 2014 Barometer found high levels of intimate and non-intimate partner violence in six SADC countries including South Africa. In particular, marital rape was reported to be ‘rife’.

Combating violence against women in the public and private sphere often confronts established patriarchal structures as well as cultural, societal and religious norms. This raises the spectre of backlash which has frustrated efforts by legislators and implementers in many countries, where entire communities may be involved in conspiracies to stifle or stigmatise discussions or reporting on violence against women, rendering their very articulation taboo.

In such circumstances victims who break with traditions of silence run the risk of being shamed more than the perpetrators. The APRM Country Review Reports of Algeria, Mozambique, and Tanzania, for example, indicated that publicising domestic violence is taboo, leading to non-pursuit of meaningful remedies for victims and survivors. Law enforcers tend to reflect societal attitudes, creating structural barriers to accessing justice. The Country Review Report of South Africa noted that in school settings where sexual violence is a major challenge, too often school officials conceal the acts and delay disciplinary action against perpetrators at the expense of the victims.

The 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action highlighted violence against women as one of 12 areas of critical concern. It emphasised periodic review and modifications to legislative frameworks for eliminating violence against women to make them more effective, along with the prevention of violence and the prosecution of offenders, the protection of women subjected to violence and access to just and effective remedies (including compensation), indemnification and healing of victims and rehabilitation of perpetrators.

The protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, 2003, saw African Heads of State continue with the struggle to combat gender-based violence within the African context. It forms one of the key standards for the APRM to determine commitment to protection and promotion of women’s rights in Africa by member states.

Much has been made of the limitations of a voluntary, non-sanctioning mechanism like the APRM, but analysis of 16 countries reviewed under the APRM indicates some quick wins in governments’ responsiveness to combating gender-based violence. In Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, South Africa and Uganda, non-state actors continue to be pivotal for societal re-engineering towards attitude transformation, in a bid to foster new cultures and norms towards gender equality. Further, many reviewed countries have adopted anti-gender violence legislation, although sensitive areas like marital rape in Ghana, Mauritius, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia remain unregulated.

However, many governments are yet to establish comprehensive reforms in key institutions like the police, judiciary and social welfare systems, and poor implementation frameworks persist. Countries like Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda are struggling to adopt victim-centered approaches that promote the rights of survivors of abuse and violence. In countries emerging from conflict, such as Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Uganda, the mechanisms for dealing with reparations for survivors of gender-based violence and appropriate transitional justice mechanisms have been inadequate.

The phenomenon of violence against women is deeply complex; decades of acceptance have entrenched and normalised it, requiring radical transformative countermeasures by governments, non-state actors and communities. The APRM can provide the agency for critical dialogues around this and monitor implementation of government commitments to end violence against the women of Africa. Holistic national frameworks that address the issue of violence against women within the context of gender equality and empowerment are vital, together with effective preventative and multidimensional remedial efforts from law enforcers, legislators and judicial officers among others.

Critical conversations geared towards dismantling harmful cultures and socio-cultural constructions that trigger or increase women’s vulnerability to violence must backstop meaningful and effective sanctions mechanisms, to ensure a safe and violence free Africa for women.

Laura Nyirinkindi is a Ugandan lawyer and gender activist, who has participated in six Country Review Missions of the APRM. She has also studied gender and governance in Africa extensively, including through analysis of APRM Country Review Reports. She was recently a guest of SAIIA in Johannesburg. This article was first published by the Mail & Guardian.