Executive summary

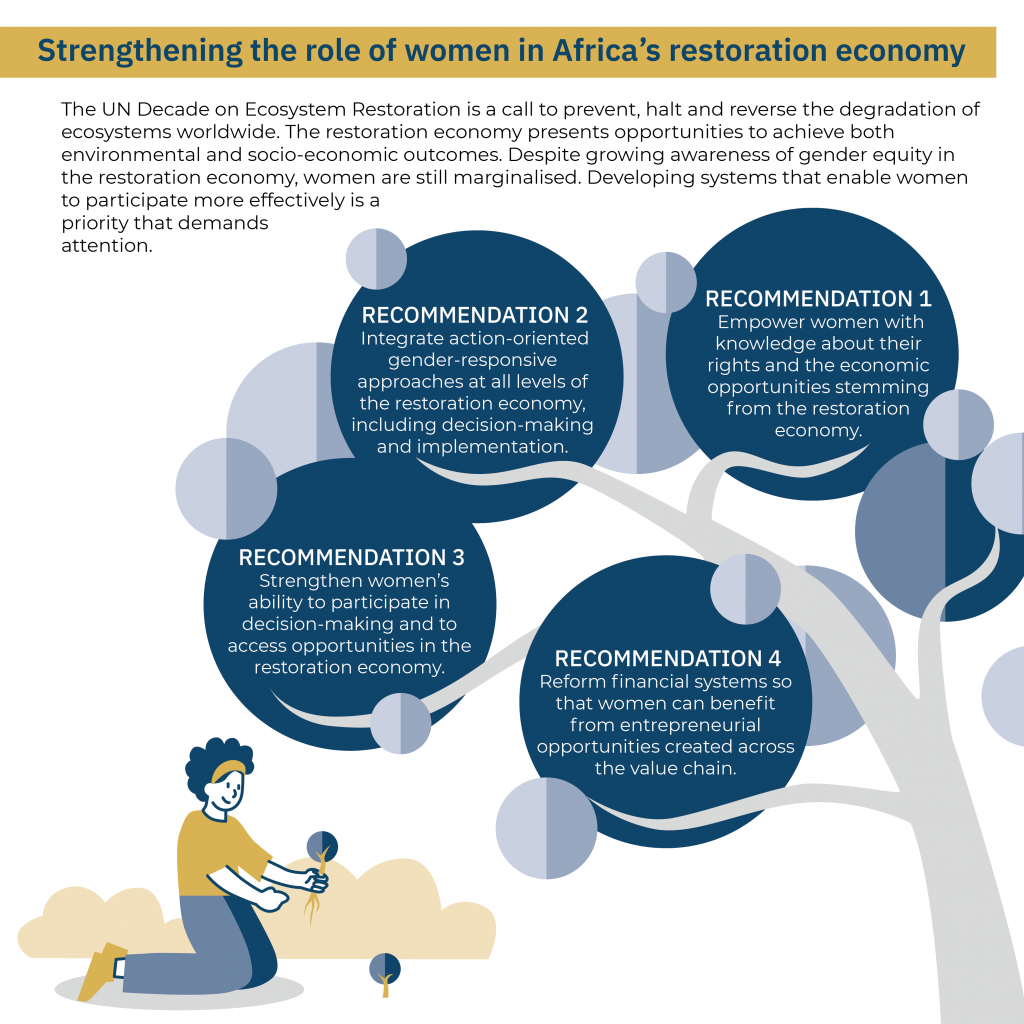

Despite increasing recognition of the roles and opportunities for women in ecological restoration, women typically still have less social, economic and political power. This has negative consequences for their equitable participation in the restoration economy.

Gender equity is enshrined in numerous policy and legal frameworks; however, women in Africa continue to experience discrimination and gender inequality.

Gender equity necessitates, first, that women must have opportunities to engage equitably in all dimensions of the restoration economy, from decision-making and process development to implementation, monitoring and evaluation. Second, women need to be empowered economically to participate in, and equitably benefit from, the restoration economy.

Empowering women’s participation in the restoration economy requires a multidimensional approach in order to address social, economic and systemic barriers. Developing systems for women’s empowerment in the restoration economy is a priority that demands attention from regional and national planners, practitioners and funders.

Introduction to gender equity in the restoration domain

The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration is a call to action to prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of ecosystems worldwide. The restoration economy has emerged as the practice of ecological restoration has grown. Ecological restoration is broadly defined as the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been damaged or degraded.1Donovan Kotze, ‘Africa’s Restoration Economy: Insights from South Africa’s Wetlands’ (SAIIA Policy Briefing 236, South African Institute for International Affairs, Johannesburg, 2021), https://saiia.org.za/research/africas-restoration-economy-insights-fromsouth-africas-wetland. The restoration economy refers specifically to economic activity relating to ecological restoration initiatives. A range of benefits are generated through the restoration economy, including developing the economy and creating jobs in rural areas, enhancing social networks, developing skills and connecting people to their natural environments.2Marisa Lia Formosa and Erin Clover Kelly, ‘Socioeconomic Benefits of a Restoration Economy in the Mattole River Watershed, USA’, Society and Natural Resources 33, no. 9 (2020): 1111–1128. DOI: 10.1080/08941920.2020.1718815. It also contributes to national economic growth.3Todd BenDor et al., ‘Exploring and Understanding the Restoration Economy, USA’ (Working Paper No. 2014-01, University of North Carolina’s Centre for Urban & Regional Studies, 2014), https://curs.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/400/2013/05/BenDor-andLester-Exploring-and-Understanding-the-Restoration-Economy.pdf.

Women and men differ in how they interact with and depend upon natural resources and in how they use ecosystems. This influences the products they acquire and the benefits they derive. The importance of recognising the different roles that women and men play in the use of natural resources is increasingly recognised as being essential in ecological restoration initiatives. This recognition allows for their differentiated inputs and promotes specific responses that women and men could and should undertake. However, despite the increasing recognition of the importance of gender equity and the empowerment of women in ecological restoration, women typically still have less social, economic and political power.4Juliet Blum and Dorothée Herr, Gender Equity Is Key to Mangrove Restoration (IUCN Global Forest and Climate Change Programme, with the support of International Climate Initiative (IKI), 2017). This has negative consequences for equitable participation in the restoration economy specifically. The need to develop systems that enable women to effectively contribute to, and equitably benefit from, the restoration economy is a priority that demands attention. Furthermore, the restoration economy, given that it is at an emerging state, is also an opportunity to promote gender equity, especially in the rural African context.

Understanding gender equity agendas

Gender equity is enshrined in several international declarations and conventions, including the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular SDG 5 on gender equity, also highlight the fact that gender equity is a fundamental human right and something that is required as a foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world.5UN, Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, Sustainable Development Goals 2030, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality. The entity UN Women, in partnership with the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, has also developed recommendations on ways to integrate a gender perspective in the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework.6Convention on Biological Diversity, A Gender-Responsive Process.

The AU recognises that gender equity is a fundamental human right and an integral part of regional integration, economic growth and social development. The AU has developed a strategy on gender equality and women’s empowerment, with the aim of enhancing the inclusion of women in Africa’s development agenda. The strategy has six focus areas, the first of which specifically focuses on women’s economic empowerment and sustainable development. It recognises that women’s empowerment is key to growth, prosperity and sustainability. It also addresses women’s rights as spanning all spheres including social, political, legal and economic, and demands equal and effective participation by women in the economy and sustainable development.7AU, ‘Gender Equity & Development’, 2021, https://au.int/en/gender-equality-development. Gender equity also features prominently in the aspirations, flagship programmes and key activities encapsulated in the AU’s Agenda 2063.

Women represent half the population of Africa, yet, despite the numerous international and regional declarations and policy frameworks, they continue to experience discrimination and inequality. Although there has been some progress towards improved gender equity in Africa over the last decade, many on-the-ground challenges persist as a result of discriminatory local laws and social norms that remain pervasive. These challenges are reflected in differential social, educational, economic and cultural situations. Achieving economic equity remains a significant challenge because of the exclusion of women from economic activities and financial systems.8Nomsa Daniels, ‘Women’s Financial Inclusion in Africa: Barriers, Costs and Opportunities’, BUWA, Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, 2014, https://www.issuelab.org/resources/21889/21889.pdf; Hanan Morsy, ‘Access to Finance: Why Aren’t Women Leaning In?’, Finance & Development 57, no. 1 (2020): 52–53, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/03/africa-gendergap-access-to-finance-morsy.htm; Cherifa Klaa, ‘Role of African Women in Development and Economic Life: Reality and Challenges’, International Journal of Inspiration & Resilience Economy 4, no. 1 (2020): 1–9. DOI: 10.5923/j.ijire.20200401.01 Furthermore, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic could reverse some of the progress that has been made on gender equity and women’s rights. The coronavirus outbreak has exacerbated existing inequalities for women across multiple dimensions, including the economy.9UN, Sustainable Development Goals.

Numerous examples from Africa show that integrating gender-responsive approaches into ecological restoration initiatives is not only key to their ecological success, but also generates additional value in supporting the livelihood activities of both women and men.10Juliet Kariuki and Regina Birner, ‘Exploring Gender Equity in Ecological Restoration: The Case of a Market-based Program in Kenya’, Ecological Restoration 39, no. 1–2 (2021): 77–89; Kotze, ‘Africa’s Restoration Economy’; Blum and Herr, Gender Equity. Gender-responsive approaches need to be mainstreamed into the restoration economy, in recognition of the critical contribution of women, in addition to protecting their fundamental right to equity.

What is needed to empower women in the restoration economy?

Gender equity in the restoration economy cannot be confined to equitable benefit-sharing. Gender equity necessitates, first, that women must have opportunities to engage equitably in all dimensions of the restoration economy. This should vary from decision-making and developing restoration economy systems and processes to implementing, monitoring and evaluating initiatives. Second, women need to be empowered economically to participate in, and equitably benefit from, the restoration economy.

- Empower women to engage equitably in developing the restoration economy

Ecological restoration should be aligned with how local people use and value ecosystems,11Kotze, ‘Africa’s Restoration Economy’. which requires it to reflect the perspectives of both women and men. Consequently, the restoration economy also needs to align with the perspectives of both women and men. Women have a vital role to play in the transition to greener and more equitable economies based on their unique knowledge and perspectives.12Catriona McLean, ‘The Green Economy Mustn’t Forget Gender’, Green Economy Coalition, March 08, 2020. A gender-responsive approach must, therefore, acknowledge women not as passive beneficiaries, but as active decision-makers and drivers of the development of a robust restoration economy.

In traditional rural settings in Africa, which are characterised by entrenched inequitable structures and barriers, women are under-represented in decision-making processes and structures, and have reduced influence in the decision-making process.13Blum and Herr, Gender Equity; McLean, ‘The Green Economy’. Cultural and social norms that are imposed on women in patriarchal societies have entrenched gender inequality to the extent that this is accepted as the norm by decision-makers and often by women themselves.

Although there is increasing awareness about the need to mainstream gender equity, there continue to be barriers to active participation in decision-making by women. Even where women are represented in decision-making structures, they are often token or passive participants. Participatory approaches do not guarantee inclusive decision-making; the power dynamics between men and women remain.14Hannah Patnaik, ‘Gender and Participation in Community Based Adaptation: Evidence from the decentralized climate funds project in Senegal’, World Development 142, no. 3–4 (2021): 105448. DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105448. Because of this, representation does not necessarily equate to active participation. This can mask the fact that there is gender inequality, and risks decision-making processes being driven by gendered interests. This leads to the development of local restoration economies that maintain financial control and economic benefits primarily in the interests of men.

Ecological restoration projects in general still overlook human elements of restoration, including gender issues, which tend to be insufficiently considered in restoration planning, implementation and monitoring.15Ludmila P. de Siqueira et al., ‘Gender Inclusion in Ecological Restoration’, Restoration Ecology 29, no.7 (2021): e13497. DOI: 10.1111/rec.13497. Accordingly, there is a risk that this lack of attention contributes to the marginalisation of women in the restoration economy. To counter this, gender equity should be considered to be both a driver of the restoration economy and a measure of success, as it is critical to the development of a sustainable and just restoration economy.

- Empower women economically to participate equitably in the restoration economy

Equitable participation in the restoration economy implies that women have access to opportunities to participate beyond merely as providers of labour to restoration projects. Women should have access to opportunities to develop and participate in interventions across the value chain. The restoration value chain includes primary elements such as:

- a supply of inputs;

- operations and management;

- the distribution of outgoing products; and

- a range of support services such as maintenance, product marketing and publicity.

The restoration economy also includes opportunities for circular linkages associated with restoration interventions (eg, reusing, repurposing and recycling products and materials). This creates ripple effects, or multipliers (eg, through value addition and beneficiation) in the economy. These value chain elements collectively contribute a range of job creation and entrepreneurial opportunities, and generate products and services that provide a diversity of non-monetary benefits for local people and broader society. Women’s unique knowledge and perspectives positions them to play a vital role in the development of a robust value chain and an equitable restoration economy.

Harnessing the economic opportunities across the value chain requires skills and capacity, including both human and financial dimensions. Financial capacity is largely determined by access to start-up capital. Economic inequalities between men and women manifest in various ways, including in asset ownership. In many cultures, men traditionally own household assets, such as land and the family home. These are the assets that banks require as collateral to access finance. This has implications in terms of access to finance and, therefore, largely excludes women from securing loans to start, operate or expand an enterprise.16Caroline Kende-Robb, ‘To Improve Women’s Access to Finance, Stop Asking Them for Collateral’, World Economic Forum, June 18, 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/06/women-finance-least-developed-countries-collateral. Women are less likely to secure loans than men, which has a knock-on effect for entrepreneurship and access to productive inputs.17Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser, ‘Economic Inequality by Gender’, Our World In Data, March 2018, https://ourworldindata.org/economic-inequality-by-gender. A lack of asset ownership as a result of customary and patriarchal systems is a serious barrier to women being able to start enterprises and equitably harness opportunities in the restoration economy.

Although significant progress has been made in facilitating improved access to financial services, barriers to financial inclusion and economic empowerment remain. For example, in 2017 the World Bank reported that only 37% of women in sub-Saharan Africa had a bank account.18Morsy, ‘Access to Finance’. Barriers to economic empowerment of women include legal frameworks, culture and access to financial services.19Statistics South Africa, Economic Empowerment, Gender series IV: Economic Empowerment 2001-2017 (Report No. 03-10-17, Pretoria, 2018). From a micro perspective, having access to a suite of financial services enables women to invest in themselves and their families, or to invest in a small business or other financially productive activities. From a macro perspective, women’s economic empowerment is recognised as a prerequisite for inclusive and equitable economic growth, and sustainable development.20Robin J. Lewis et al., ‘Bridging the Financial Inclusion Gender Gap’, Brookings, TechTank, April 1, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2016/04/01/bridging-the-financial-inclusion-gender-gap.

Empowering women economically to participate in the value chain of the restoration economy requires urgent interventions to address capacity constraints. This includes the knowledge and skills to recognise and harness opportunities, to access start-up capital and financial services, and to develop business literacy to manage and expand initiatives.

Conclusion – actions to break down barriers to women’s participation

Empowering women’s participation in the restoration economy requires a multidimensional approach to address social, economic and systemic barriers:

- Integrate action-oriented approaches to promote gender equity in developing the restoration economy

Actively address gender equity at all levels of the restoration economy, including decisionmaking and implementation across the value chain. Incorporate action-oriented approaches to empower women to participate in decision-making processes and onthe-ground activities, with the inclusion of social learning and participatory tools and mechanisms. Evolve gender-responsive approaches to not only reflect an understanding of gender roles and inequalities, but also be proactive in encouraging inclusiveness, equal participation and the fair distribution of benefits from the restoration economy.

- Promote systemic reforms of inequitable structures and decision-making processes to embed gender equity

Gender inequality cannot be rationalised by cultural systems based on patriarchal values. There needs to be a transition towards systems that reflect the constitutional value of human rights, equity and freedom. Systemic inequalities that underlie gender inequality – such as unequal structures, hierarchies and power relations – need to be addressed when developing restoration economy initiatives. Long-term interventions that embed gender equity need to be encouraged and supported. Examples include incorporating meaningful participation into decision-making systems and processes; reforming customary laws that are barriers to women’s access and control over assets (by addressing laws affecting marital property, inheritance and titling of land); economic empowerment; and universal education. These systemic changes will support the realignment of power relations between women and men, which will help to address gender imbalances in decisionmaking powers and access to opportunities in the restoration economy.

Strengthen and accelerate ongoing reforms in financial systems

This includes interventions such as the following:21Carolina Trivelli et al., ‘Gender Economic Equity: Financial Inclusion for Women: A Way Forward’ (Think 20, G20 Insights, CIPPEC, Argentina, 2018).

- Accommodate alternative sources of collateral to improve access to capital and credit, to compensate for discriminatory customary laws that are barriers to women’s control over marital property and inheritance of land, which is a key factor in the capital and credit shortages that women face.

- Establish non-discrimination in access to credit, which is not based on gender and marital status.

- Promote new ways of building credit records through the use of new technologies and non-traditional information-based credit scorings.

- Establish financial services to support women’s businesses, such as access to sufficient financial information and reduced entry, access and usage costs to financial services.

- Support the creation of women’s business associations and networks that support collective action, such as bringing the barriers and issues affecting women-led business development to the attention of developers and financial service providers.

- Invest in knowledge empowerment

Inequality between men and women can be reduced by improving the education of women. Capacity development is needed to enable women to understand their rights, roles and economic empowerment opportunities presented by the development of the restoration economy. Capacity development can include supporting women to organise themselves and form associations. This facilitates the development of social capital and collective action, which positions women favourably to engage actively in opportunities in the restoration economy and to lobby for reforms to inequitable systems and practices.

Finally, synergies between the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and the Sustainable Development Goals 2030, and specifically SDG 5 on gender equality, could be harnessed to promote the importance of gender equity and the need to empower women to participate in the restoration economy. Emphasising the connection of the SDGs and the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration could be a powerful tactic to motivate for the commitment of capacity and resources by all relevant sectors to support action-oriented approaches and systemic reforms for empowering women to participate equitably in the restoration economy.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of SIDA for this publication.