President Zuma announced his new cabinet on Sunday 25 May 2014 – retaining the services of Minister of International Relations and Co-operation (DIRCO), Maite Nkoana-Mashabane. The department will, however, welcome two new deputy ministers: Ms Noma-India Mfeketho, former Mayor of Cape Town and more recently, deputy speaker of parliament; and Mr Llywellyn Landers who has been an MP since 1994.

Interestingly, DIRCO is one of only four ministries out of a total of 35 which has two deputy ministers. This signifies the scope and importance of the work of this ministry, which is responsible for the management of relations with 309 foreign representative offices in South Africa, while South Africa is represented in turn in 282 countries and international organisations around the world. Pretoria hosts the largest number of foreign diplomatic missions after Washington (there are 123 embassies and high commissions alongside 53 consulates from across the world based in South Africa).

Although Minister Nkoana-Mashabane’s presence signals a degree of continuity in DIRCO’s operations, the appointment of the two new deputy ministers offers an opportunity for invigoration. This overview offers insights into some of the key challenges that South Africa’s foreign policymakers should tackle in the second term of the Zuma administration.

In 2013 the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) conducted a qualitative survey aimed at garnering ‘expert’ perspectives on the impact of South Africa’s foreign policy on continental issues. A key reason for the survey was to understand better where and how South Africa could work more effectively with partners in the region (and abroad) on bringing peace and stability to Africa.

South African foreign policy is often viewed as highly value-driven and cast as contributing to Africa’s Renaissance, good governance, peace and stability. However, foreign policy decisions are not simply a matter of applying ethics and values. Rather, these decisions are often complex, needing to calculate trade-offs between competing domestic and international imperatives, as well as short and long term interests. Given this complexity, SAIIA chose to garner opinions from foreign policy practitioners – experts – who are able to understand the limitations within which policymakers operate.

The survey of foreign policy practitioners was completed in two stages – in Pretoria and Addis Ababa. Respondents participated in a rigorous hour-long qualitative interview where they were prompted to provide insights into various aspects of South Africa’s foreign policy. Interviews were granted on the basis of anonymity which has had a causal effect in data accumulation and analysis. While the qualitative methodology provided scope for the richness and nuances in responses, this methodology makes it inherently difficult to collate responses and draw comparisons from them. Nevertheless, strong parallels and themes did emerge.

In the South African leg of the survey, interviewers spoke with representatives from diplomatic missions represented in Africa and from other parts of the world. Respondents were represented from all continents except South America. Despite various attempts to solicit interviews with representatives from Latin America, none agreed to participate. This is an unfortunate shortcoming of the survey as it presents a gap in the research. During the Ethiopian leg the focus was primarily on regional organisations represented in Addis Ababa.

Below are some of the findings from the South African leg which may be of relevance to a new administration as it embarks on its next 5-year term.

FINDING 1: SOUTH AFRICA’S FOREIGN POLICY DIRECTION IS UNCLEAR

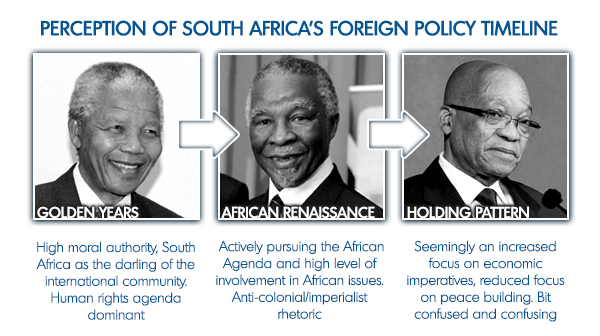

Since its transition to democracy, South Africa’s stature in the international arena has undergone a considerable evolution. The peaceful transition in 1994, augmented by the conciliatory leadership of President Mandela meant that South Africa entered the international stage with considerable moral authority. The idealism of the Mandela epoch created expectations about the role that South Africa could and should play internationally. However, the value-driven foreign policy associated with his term that promoted human rights as a central pillar of its framing has proved to be difficult for successive administrations to live up to.

The results of the survey showed that respondents were overwhelmingly of the opinion that the drivers of South Africa’s foreign policy have become obfuscated over time. While some acknowledge that controversial foreign policy decisions like the denial of the Dalai Lama’s visa in 2009 and a subsequent controversy in 2011 are illustrations of a country still maturing into its role in the international arena, the vast majority of respondents felt uncertain as to what Pretoria’s foreign policy priorities were.

Respondents recall President Mandela’s administration as one focused on promoting human rights. They found his leadership firmly stamped South Africa’s moral authority on the world. Similarly, President Mbeki is remembered as an African visionary who championed the ‘African Renaissance’. Under President Mbeki, it was felt, Africa began to take centre stage as he promoted many reforms on the continent. Despite his controversial stances on the Ivory Coast and domestically, his position on HIV/Aids, President Mbeki’s term is attributed with expounding a profound vision of African leadership.

When asked to provide impressions of South Africa’s foreign policy under the leadership of President Zuma, respondents overwhelmingly declared that it was confusing. Non-African respondents in particular expressed uncertainty about what South African foreign policy was, saying that they felt it lacked strategic direction and as such, made it difficult to predict. Both African and non-African respondents raised the concern that South Africa was focused on pursuing a ‘trophy diplomacy’ – trying to rise above its station before maturing as a geopolitical entity, and possibly losing touch with its nearest neighbours and traditional partners as a result.

Recommendation

There is no doubt that South Africa’s foreign policy is informed by the country’s developmental challenges, as it tries to harness its international engagements to accrue tangible economic and ‘peace dividends’ to its citizens. However the country has failed in its ability to communicate the country’s strategic intent when engaging in the international arena. The new administration should move swiftly to review the South African Foreign Policy White Paper ensuring that it clearly espouses a better balance between its relationship with Africa, the West and the emerging South. It is useful to garner additional and broad-based inputs into this important policy document that is supposed to guide the country’s foreign policy.

FINDING 2: THE AFRICA FOCUS IS LAUDABLE

Respondents were asked to provide an indication of what they perceived South Africa’s foreign policy priorities to be. Four inter-linking themes emerged:

- Economic Issues were highlighted as an important thrust of South Africa’s diplomacy. These issues were not only linked to improving trade, investment and economic integration. The pursuit of economic development domestically was recognised as a key goal of the country’s diplomacy among the majority of those interviewed. South Africa’s notion of itself as a ‘developmental’ state that pursues international engagements principally to ensure dividends for its citizens is an important part of this narrative.

- Security is a second theme that emerged as a perceived priority for South African foreign policy makers. African diplomats in particular, felt that the South African government expended considerable energy in its foreign policy focus on the attainment of security and stability in its region.

- The third theme to emerge as a perceived priority and a strong South Africa contribution was that of contributing to peace and conflict resolution. Across the spectrum of respondents, South Africa is respected for its commitment to the peaceful resolution of conflict through negotiated political settlements. However, many expressed concern about the absence of clarity surrounding the country’s decisions to intervene in some countries and not in others. For instance, at the time when the fieldwork was conducted, media reports featured stories of the deaths of South African troops who had been stationed in the Central African Republic (CAR). Many respondents were confused as to why South Africa was involved in CAR.

- A fourth theme that emerged is the primacy of Africa in South Africa’s foreign policy. This theme intersects with the other three, as it is largely perceived that Africa takes centre stage in South Africa’s economic, political and security policies. Respondents noted South Africa’s prioritisation of long-term development strategies over short-term fixes in its engagement with the rest of the continent. Similarly, interventions in crisis situations are perceived to be more likely driven by development as an objective rather than military imperatives.

Recommendation

The clearly perceived primacy of Africa in South Africa’s foreign policy priorities is a coup for the government, and is an indication that its ‘African Agenda’ message holds traction among its recipients. Going forward, South Africa’s foreign policy should ensure that it continues to be reflective of its African Agenda. Given the perceived primacy of economic development as a foreign policy priority, South Africa should take care that the economic drivers of its foreign policy also support its ‘public goods’ agenda across the continent, ie the promotion of good governance, peace, stability and closer regional integration and cooperation. This requires a carefully framed public diplomacy married with sufficient resources and pro-active diplomatic engagement at a bilateral, regional and global level. It also implies working more closely with the main actors in South Africa’s economic and commercial diplomacy, namely the South African and regional business community.

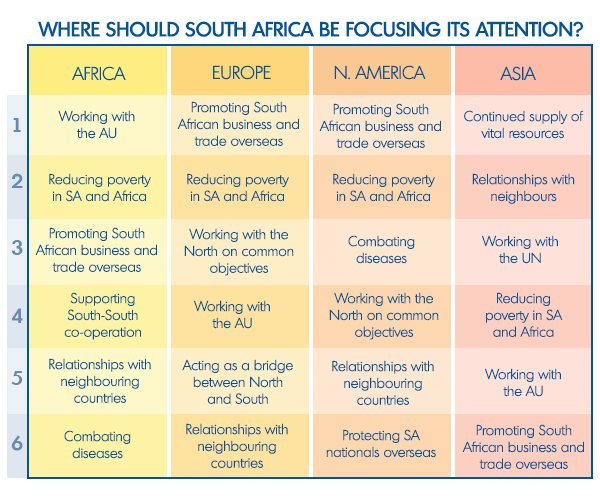

These suggestions are also reflected in the ranking of the aggregated responses from all participants in the South African leg of the survey when they were asked:

WHERE SHOULD SOUTH AFRICA FOCUS ITS ATTENTION?

- Working with the AU

- Promoting South African Businesses and Trade Overseas

- Building and Sustaining Relationships with neighbouring countries

- Reducing Poverty in South Africa and Africa

- Supporting South-South Cooperation.

The survey was able to break down these suggested priorities by region. This is a useful exercise as not only does it reveal the nuances of different regions, but a closer examination of the regions’ suggestions is also very revealing about their own foreign policy priorities and how they seek to engage South Africa.

Tellingly, the focus of Asian countries remains resource-driven, and its relegation of ‘reducing poverty in South Africa and Africa’ to 4th position, indicates that it may not be as committed to developmental concerns as Western countries – given that they locate this priority further down in their ranking compared to the West.

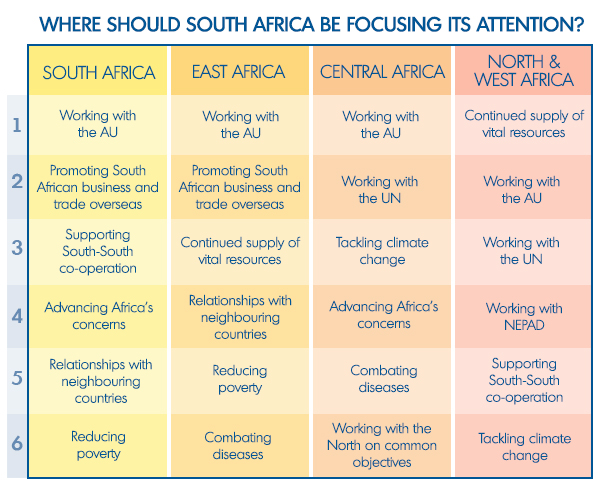

A more bifurcated view of Africa reveals that there are regional differences in priorities as well:

By and large, collaboration with the African Union trumps the list of suggested priorities, but a comparison between East Africa and Southern Africa reveals that there are a number of shared concerns, such as working more closely with the AU (priority 1); promoting South African business and trade with the region (priority 2); working on improving relations with other countries in the region (priority 5 for Southern Africa and priority 4 for East Africa) and lastly, working together on reducing poverty (priority 6 for Southern Africa and priority 5 for East Africa).

This finding reveals a potential for South Africa to play a stronger role in harmonising interaction between these two regions, particularly in the context of the Tri-Partite Free Trade Area that is currently under negotiation between COMESA, the ECA and SADC. These negotiations, which aim to create a single economic space between Southern and Eastern Africa and to promote small and medium enterprise development – a key factor for the growth of both communities – have been stalled by disagreement. This survey finding tells the story that there are indeed common threads undergirding the initiative – which ought to be drawn on in resolving some of the tensions.

Recommendation

South Africa’s foreign policy has led to a number of positive outcomes for the country and the continent. The role that the country has played in establishing and strengthening regional multilateral organisations – both in its immediate region, and continentally – is a clear indication that South Africa is committed to a future that includes the development of its African compatriots.

Similarly, South Africa’s entrance onto the global stage has been welcomed by its brethren. However, twenty years on, there remains much to be done to entrench peace, good governance and further economic cooperation to fully harness Africa’s potential. South Africa’s foreign policy arguably enters a new phase – one that must accommodate competing interests without compromising its core values that are espoused in its constitution.

To do this, South Africa can play a constructive role on the continent by focussing its foreign policy on the formulation of strategic partnerships. By identifying and cultivating stronger relationships with key countries in and outside the continent that share its approach, without being always the most powerful or biggest actors, it becomes possible for the government to advance a truly African Agenda – one that is built on solidarity, trust, and over time, common values and a common vision.

SAIIA commissioned IPSOS, an independent survey company, to conduct the South African Foreign Policy Survey with SAIIA researchers in attendance. The South African leg of the survey entailed 40 interviews with diplomats based in Pretoria and was conducted between December 2012 and May 2013; and the Ethiopian leg of the survey entailed 20 interviews in Addis Ababa over two weeks in October 2013. This project was made possible with core support from the Konrad Adenaur Stiftung (KAS), the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) and the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA).