The sexual abuse and exploitation of women – in war and peacetime – is one of the most widespread and overlooked phenomena. Frequently exposed to violence and sexual exploitation by armed combatants, women and children have throughout history, been kidnapped, raped and forced into work or to fight on the frontline for causes that are not their own. Only since the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunals in Yugoslavia and Rwanda has sexual violence come to be regarded as an international crime, a crime against humanity and, therefore, a grave infraction of the Geneva Conventions.

Exposure to gruesome acts of sexual violence make women and children in conflict-affected areas some of the most vulnerable groups of people in the world and in dire need of protection. It is all the more unconscionable then, when the abuse is perpetrated by United Nations peacekeepers deployed in missions whose mandate is to protect them.

Understanding the scope of the problem

The blight of UN officials involved in sex for food scandal first came to light in the early 2000s. UN aid workers in Sierra Leone and surrounding countries in West Africa were exposed for trading humanitarian aid in exchange for sex. The “food-for-sex” scandal as it is commonly known, was swiftly followed by reports in 2005 of sexual misconduct by peacekeepers in the DRC.

These two events and the ensuing global outrage that they received cast a long shadow over the work of the UN, forcing it to begin a thorough examination of the occurrences of sexual abuse and exploitation in its missions and peacekeeping operations, and its policy responses to them.

While sexual exploitation may not be as heinous an act of violence such as abuse or rape, it is nevertheless treated by the UN as an equally taboo practice. In a 2003 bulletin published by the then Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, sexual exploitation is defined as “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another”. This definition removes the age of consent as a prerequisite for the comital of a crime, opting instead to highlight the skewed power-dynamic between peacekeepers and victims as the over-arching determining factor of abuse.

Embedded in this position is the recognition that people in post-conflict environments are often living in poverty with limited prospects for employment, and that peacekeepers who earn disproportionately more, are innately put in positions of power that they then abuse when they engage in transactional sexual acts. It takes into account that women and girls are often forced into transactional sexual arrangements because they have no other prospects to earn an income. In some instances money exchanges hands, but in others it is equally common for sex to be traded for food and provisions. The proliferation of these illicit activities has also highlighted the need for peace operations to play a role in improving the employment prospects and employability of local communities, so that women have other options to earn a wage.

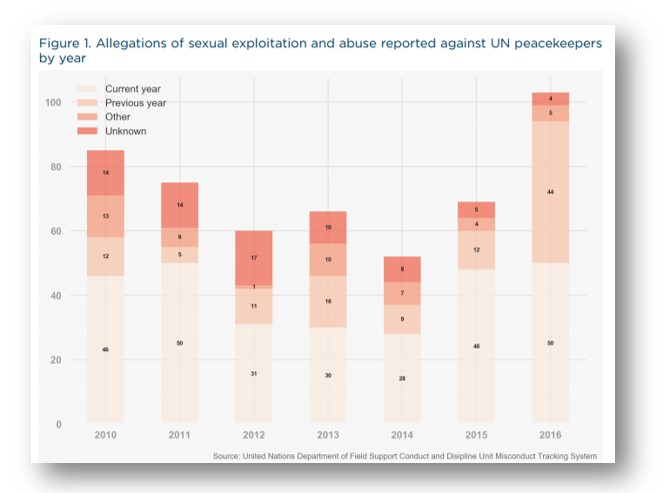

Source: United Nations Department of Field Support Conduct and Discipline Unit Misconduct Tracking System

Of the 2000 cases of sexual misconduct reported to the UN over the past 12 years, 700 emanate from the DRC. Another report shows that 300 of these 2000 cases involve children. This geographic and demographic spread is however impugned by the fact that UN statistics on this issue (while steadily improving) are notoriously inaccurate. Record collection is impeded by under-reporting and chronically bad record-keeping by the UN.

Since 2014, allegations of sexual abuse and rape of children in the Central African Republic have further scandalised UN operations. In 2015 it even led to the unprecedented high-profile dismissal of the Special Representative of the SecretaryGeneral in the CAR, Babacar Gaye, for his failure to adequately address the issue. In Africa, reports of sexual exploitation and abuse perpetrated by UN peacekeepers have come from Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, South Sudan and Somalia.

Fighting the scourge from within

For the UN, battling this scourge within its ranks has been problematic. Administrative and legal hurdles have prevented the organisation from developing sufficient punitive measures – particularly against peacekeeping troops during UN deployments. Status of Force Agreements (SOFAs) between deploying countries and the UN determine the parameters of peacekeeping engagements and ensure that nation-states maintain ultimate jurisdiction over their troops. This means that the decision to prosecute offending soldiers them resides at the national level. This has led to a lack of follow-through by deploying administrations – either from a lack of political will to do so, or because the crimes in question have not been domesticated in home countries.

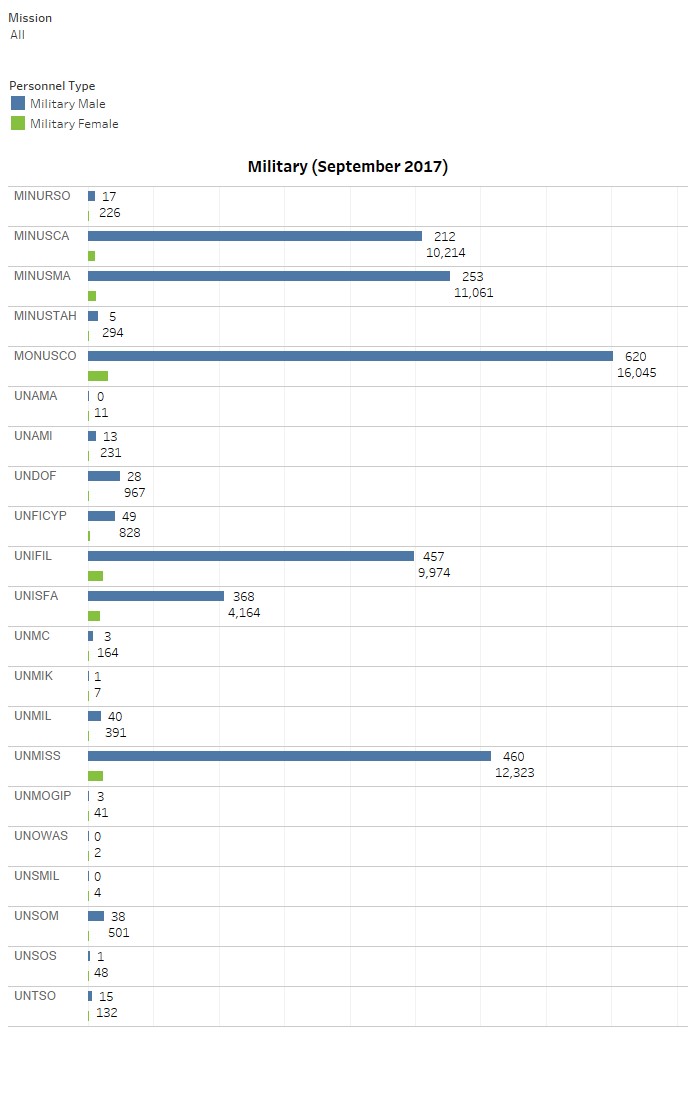

The organisation’s failure to respond to or prosecute allegations has had the perverse impact of discouraging victims from reporting incidents of rape and sexual abuse. Furthermore, the under-deployment of female peacekeepers hinders reporting, as it is believed that female victims find it easier to report crimes to other females. This is one of the reasons that the case has been advanced to encourage the deployment of more female peacekeepers. So far, only India and Bangladesh have ever lived up to this call. While UN records do reflect rising numbers of female UN peacekeepers, the graph below illustrates how paltry the numbers are in reality:

Source: peacekeeping.un.org/en/gender

The UN’s response

In the aftermath of the various scandals that have rocked the UN, it has implemented several preventive and responsive measures aimed at eradicating this phenomenon from its ranks. It has also drafted several resolutions on women, peace and security and sexual violence in armed conflict, and commissioned several independent reports on how best to tackle the matter.

Resolution 1325, adopted in 2000, required the Secretary-General to report regularly to the UN Security Council on the issue of women and peace and security. It called for the gendered training of troops. This resulted in practices like educating peacekeeping troops about the consequences of engaging in transactional sexual relation with locals as well as incentives to increase the number of female peacekeepers.

Most importantly, it led to the adoption of Resolution 2272 in March 2016 that deals explicitly with the perpetration of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers. This resolution makes significant strides is advancing the UN’s position on sexual violence by peacekeepers by first clarifying and reinforcing the Secretary-General’s authority to repatriate and replace peacekeepers when there is sufficient evidence to suggest sexual exploitation by members of national contingents. In June 2017 600 peacekeepers from the Republic of Congo were repatriated from CAR as a consequence.

Secondly, the resolution tasks member states to investigate and report on allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse in order to hold perpetrators accountable and to keep the UN Secretary-General appraised of the progress of investigations. In a similar vein, civil society organisations are lobbying for an end to impunity for peacekeepers. The Code Blue campaign, for instance, has called for the establishment of a special courts mechanism within the UN to prosecute perpetrators.

Reforms

When Secretary-General António Guterres assumed office in January 2017, he also announced sweeping reforms designed to make the global body more efficient and streamlined. Reforms, followed by an extensive review process also provide a precipitous opportunity to review the UN’s approach to sexual abuse and exploitation in peacekeeping. Indeed, recent efforts, crystalised in Resolution 2272, provide new impetus and support to the broader reform agenda.

While laudable progress has been made, there lies much work in rolling out the initiatives of Resolution 2272. For this to be successful, sustained political will is a prerequisite. The UN needs to also address some of the pitfalls that might emerge – for instance, how to balance the need to rapidly deploy peacekeeping troops, with the extra time it takes to vet soldiers and the bureaucratic administration that comes with this. Another potential pitfall related to more stringent measures relates to how to sustain levels of troop contributions in the face of greater bureaucracy, administration – and perceived impediments to their jurisdiction.

While these are hurdles are not insurmountable, they pose more challenges for the UN in attempting to strike a balance between the need for boots on the ground and to provide security to citizens. The march toward progress may be slow, but it is worth bearing in mind that peacekeepers are mandated first and foremost to protect citizens. Always, peacekeepers must be protectors, not predators.