Recommendations:

COVID-19 has impacted global trade. South Africa needs to adapt to this new reality by:

- strengthening partnerships among all stakeholders (government, business and civil society) and empowering existing platforms, like the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC), which should adapt to new and flexible ways of working.

- updating and revising the South African Trade Policy Strategic Framework to take into account this ‘new normal’ and using this as the basis for the development of a shared Southern African Customs Union (SACU) trade strategy.

- developing clear positions on trade in services and digital trade that reflect increased digitisation of the global economy and the need for ongoing innovation.

- remaining committed to international cooperation on trade and develop a vision of how it wants the World Trade Organization to operate in the 2020s.

- committing to regional integration at all levels. Investment in infrastructure has been highlighted as critical in light of COVID-19 and efforts should continue to address the funding gap as well as project preparation requirements.

- revising the SACU revenue formula to enhance transparency and predictability.

- concluding the negotiations of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and implementing commitments to increase intra-African trade and investment.

Introduction

This decade got off to a challenging start with the COVID-19 pandemic impacting all aspects of life in South Africa. Trade is no exception and this paper is written at a time when it is not clear what the future will hold for South African traders or the multilateral trading system. The authors have reflected on key aspects of South Africa’s existing trade partnerships and captured issues that could form part of a trade policy for the 2020s. It is still a time of extreme uncertainty and the economic climate is rapidly changing in South Africa. This presents particular difficulties for policymakers and adaptability will be a defining trait required for the decade ahead.

Impact of COVID-19 on trade

At the forefront of the minds of policymakers in 2020 will be dealing with the economic devastation wreaked by COVID-19. The World Trade Organization (WTO) estimates that global trade will fall by between 13% and 32% in 2020.1 World Trade Organization, ‘Trade Set to Plunge as COVID-19 Pandemic Upends Global Economy’, press release no. 855, April 8, 2020, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm. This is driven by both supply and demand forces, with the consumption and production of goods and services reduced as countries have shut down their economies to deal with the pressing concerns of the health emergency caused by COVID-19. With the evolution of the crisis starting from China and then spreading to other key economic centres in Europe and the US, the vulnerability of global value chains (GVCs) has been exposed together with the necessity of logistics to get trade moving. GVCs and trade facilitation were concepts at the heart of trade policy debates in the last decade, but they will now require rethinking as weaknesses are addressed. For example, the disruptions due to lock downs in response to COVID-19 have highlighted the vulnerabilities of industries that rely on dispersed supply chains based on a ‘just in time’ approach, including hi-tech manufacturing. In the future it may be that firms adopt more of a ‘just in case’ system that puts less emphasis on supply chain efficiency.2ING Group, Pandenomics: How Covid-19 could Change the World (London: ING Group, April 7, 2020), https://think.ing.com/reports/pandenomics-how-covid-19-could-change-the-world/.While transport options remain restricted, there is scope to focus more on regional value chains and opportunities in the immediate neighbourhood.

Trade restrictions have been one of the tools used by countries to deal with COVID-19. The response has included export controls and the reduction of tariffs, particularly on medical supplies, personal protective equipment and pharmaceuticals. These have gradually been removed as countries reopen their economies, but it is expected that we will now see a renewed focus on import substitution as a policy preference. This has already been flagged in the thinking of the African National Congress (ANC) as it sets out a vision for a ‘new South African economy’.3Marianne Merten, ‘SA’s Economy after the Covid-19 – an Iron Fist in the ANC’s Velvet Glove’, Daily Maverick, June 5, 2020,https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-06-05-sas-economy-after-the-covid-19-an-iron-fist-in-the-ancs-velvet-glove/#gsc.tab=0.It suggests that the South African government will continue to use trade policies as a tool for industrial development and increase state involvement through development finance institutions. As one COVID-19 report put it, ‘big government is back’,4ING Group, Pandenomics, https://think.ing.com/reports/pandenomics-how-covid-19-could-change-the-world/including in countries where there was a trend towards increased support for domestic industries before the pandemic. Where South Africa might continue to struggle with a state-led industrialisation process, however, is in relation to the capacity of the government to guide the necessary investments and policies, given institutional and financial constraints.

It can therefore be expected that the first part of the 2020s will see South African trade policy marked by rethinking the underlying relationships between exports, imports, industrialisation and economic development. Ideally this debate will involve all stakeholders and build on the cooperation that was seen between government, business, labour and civil society in addressing the first weeks of the pandemic in South Africa. The structures exist for dialogue, such as through NEDLAC, but these platforms will need to move beyond being rubber-stamping exercises to become inclusive environments for open and creative policy development.

Even before COVID-19, South Africa had found itself in a recession and facing increasing levels of unemployment. Before abandoning the notion of the positive role that exports can play in an open economy like ours, it will be important to ensure there is evidence to support the policy shift. The 2020s are likely to be a decade where data becomes even more readily available from a range of different sources and it will be critical for our trade policy making processes to draw upon these resources. Stakeholders should relax their traditional positions, often based on ideology, and become open to arguments driven by evidence.

All evidence points to South Africa continuing to be closely connected to other states and world markets in the coming decade. This will be through trade, investment, migration, remittances and other financial flows. The following sections explore some of the key trade relationships South Africa is expected to continue to enjoy. Now is not the time to abandon the regional integration agenda that has been at the heart of South African trade policy for decades. It is the time to learn from the pandemic by supporting innovation, trade in services and digital trade. These issues need to be captured in a forward-looking trade policy for South Africa that can then form the basis of our engagements with other members of SACU and beyond. The climate crisis also remains, albeit overshadowed in 2020 by global health concerns, and we ignore it at our own peril. There will be both opportunities and challenges for South African trade, especially in relation to agricultural products.

Southern African Customs Union

SACU is the most important trade partnership that South Africa has, but is arguably the least understood and appreciated. It is the oldest customs union in the world and is based on a unique revenue-sharing formula that allows the five member states (Botswana, eSwatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa) to divide up the trade revenues collected at the external borders. The current revenue formula was agreed when SACU was reformed and it is set out in the SACU Agreement 2002. It is complex and opaque to the broader public. This has led to tensions and misunderstanding in the past, including in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008 when SACU members questioned the revenue allocations.5Tanja Hichert, Peter Draper and Talitha Bertelsmann-Scott, “What Does the Future Hold for SACU? From Own Goal Laduma!

Scenarios for the Future of the Southern African Customs Union” (Occasional Paper 63, South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), Johannesburg, 2010), https://saiia.org.za/research/what-does-the-future-hold-for-sacu-from-own-goal-to-ladumascenarios-for-the-future-of-the-southern-african-customs-union/.

While there have been efforts to update the revenue formula and address other issues, such as the delayed establishment of common institutions,6Southern African Customs Union (SACU), ‘Review of the Revenue Sharing Arrangement’, https://www.sacu.int/category.phpcat=Review%20of%20the%20Revenue%20Sharing%20Arrangement.these have been bogged down and resulted in little progress. However, the COVID-19 crisis might provide the momentum required to reach a compromise. While it is not expected that SACU members will experience a drop in revenue in 2020 (due to the advance payment provision in the current agreement7Thomson Fontaine, Dalmacio Benicio, Joannes Mongardini, Genevieve Verdier, and Gonzalo Pastor, “The Impact of the Crisis on SACU Revenue and the Need for Fiscal Adjustment” in In the Wake of the Global Economic Crisis : Adjusting to Lower Revenue

of the Southern African Customs Union in Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland (Washington, DC: IMF, 2011), https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/IMF087/11540-9781462343492/11540-9781462343492/ch02.xml?language=en&redirect=true.), there is no doubt that there will be negative implications in later years. For example, the SACU revenue pool is significantly linked to the trade of automotives.8Frank Flatters and Matthew Stern, ‘SACU Revenue Sharing: Issues and Options’ (Policy Briefing, USAID/SEGA II, 2006),http://qed.econ.queensu.ca/pub/faculty/flatters/writings/ff&ms_sacursf_2006.pdf.Between March and April 2020 there was a decline of 89% in exports of vehicles and components from South Africa.9Justin Barnes, ‘COVID-19: The South African Auto Industry’ (Policy Briefing 6, Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies, Pretoria, 2020) https://www.tips.org.za/policy-briefs/item/3781-covid-19.The SACU Secretariat has estimated that the pandemic has reduced customs revenues by up to ZAR 7 billion per month.10Nthakoana Ngatane, ‘SACU: COVID-19 Costing Member States R7bn in Revenue Every Month’, Eyewitness News, April 30, 2020,https://ewn.co.za/2020/04/30/sacu-covid-19-costing-member-states-r7bn-in-revenue-every-month.The reduction of revenue flows will have a magnified impact on the budgets of all member states as they confront the costs of dealing with the virus and the slow-down in their economies.

The 2020s will not be the decade to abandon SACU but a chance for South Africa and its neighbours to construct a revised arrangement that builds on progress already made. This could include designing a more transparent and predictable revenue-sharing arrangement that is better able to weather shocks. The nature of the contributions made by all members to the customs union should be discussed openly so that there is a broad-based understanding of the arrangement among the public. This will help to build a coalition that can ensure the longevity of SACU.

There is also room for improvement in the trade aspects of SACU. The notion of a shared regional trade policy needs to be embraced at a practical level through the development of a SACU trade strategy. This must reflect a mutually supported shared vision that guides SACU’s participation in multilateral, regional and bilateral trade negotiations. It should go beyond simply trade in goods but also reflect shared principles in relation to trade in services, e-commerce and other trade-related issues. These will be critical for trade policy in the 2020s and it is important that SACU countries are aligned so as to maximise benefits and leverage in discussions with other trade partners. This development of a common agenda is a priority above the stalled process to establish common institutions.

African Continental Free Trade Agreement

The AfCFTA brings together the 55 members of the AU, in what is the biggest free trade area since the WTO in terms of the number of countries it includes. The general objectives of the AfCFTA, as stated in Article 3 and 4 of the Agreement, include the creation of a single, liberalised market for goods and services, enhanced competitiveness of African economies, the promotion of industrial development and sustainable socio-economic development, gender equality and structural transformation. The AfCFTA was launched on 7 July 2019 at the 12th Extraordinary Summit of the AU 11Tralac, ‘African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Legal Texts and Policy Documents’, https://www.tralac.org/resources/ourresources/6730-continental-free-trade-area-cfta.html.and the first phase was due to enter into force on 1 July 2020. This has been delayed due to COVID-19 and challenges remain in completing the negotiations on tariffs and rules of origin as well as trade in services. Complex trade negotiations make working virtually with many countries and different languages difficult.

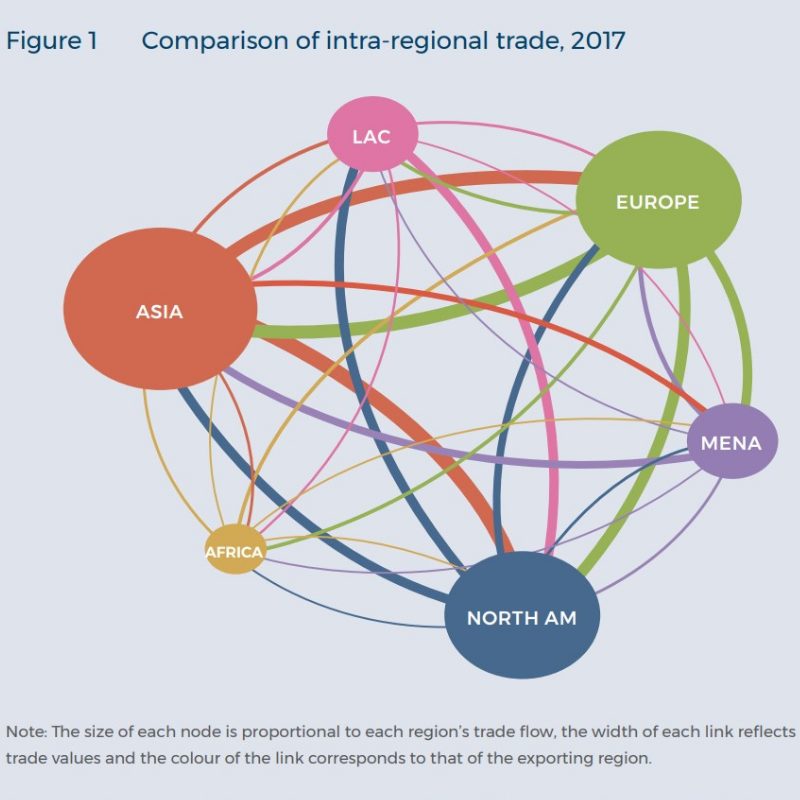

The necessity for such an agreement arises out of the realisation that African countries, for the most part, do not trade enough with one another. To illustrate, only 17% of imports in Africa are sourced from the within continent, in comparison to 60% in Europe and 70% in Asia as shown in Figure 1.12UN Conference on Trade and Development, ‘Economic Development in Africa Report 2019: Made in Africa: Rules of Origin for Enhanced Intra-African Trade’, press release, June 26, 2019, https://unctad.org/en/pages/PressRelease.aspx?OriginalVersionID=520.The reasons for this include both positive and negative factors, such as the lack of intercontinental connections and the fact that most countries produce the same commodities, and therefore tend to trade with other regions.13Helena Wasserman, ‘Africa’s New Free Trade Deal: Here’s How it will Affect South African Business’, Business Insider SA, July 11, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.co.za/africa-free-trade-deal-2019-7.It will be important to see progress in these areas if levels of intra-African trade are to increase in the 2020s. This was recognised in the development integration approach that has been followed by the South African government in a bid to ensure that trade liberalisation is supported by infrastructure development, strong governance and industrialisation.14Faizel Ismail, ‘How a Post-COVID-19 Revival Could Kickstart Africa’s Free Trade Area’, The Conversation, May 26, 2020,

https://theconversation.com/how-a-post-covid-19-revival-could-kickstart-africas-free-trade-area138223utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20May%2026%202020%20-%201632515682&utm_content=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20May%2026%202020%20-%201632515682+CID_4d508619a617 be5fee4ca831bd 253175&utm_source=campaign_monitor_africa&utm_term=How%20a%20post-COVID 19%20revival%20could%20kickstart%20Africas%20free%20trade%20area.

In the case of South Africa, the first and most immediate effect of the AfCFTA will concern the agreement to eliminate tariffs on 90% of goods over the next decade. It is estimated that intra-regional trade could grow by between 15% and 25%. The expected effect of the elimination of tariffs is that, as one of the few industrialised countries on the continent, South African manufacturers will be able to export more products within the African market. This will allow for the diversification of export markets to West and North Africa, as South African trade is currently concentrated in neighbouring countries and with SADC partners.15Tralac, ‘African Continental Free Trade Area’, https://www.tralac.org/resources/our-resources/6730-continental-free-trade-area-cfta.html.

Conversely, the cost of imported products from the rest of the continent into South Africa will also reduce. For example, within agriculture South Africa is both a destination market and a source country. South Africa mainly exports processed agricultural goods and could be in a position to acquire primary and intermediate agricultural goods from other African countries to produce higher value products.16Moses Lubinga, ‘Commentary: What does the AfCFTA Agreement Mean for South Africa’s Agricultural Sector?’, NAMC, https://www.namc.co.za/commentary-what-does-the-african-continental-free-trade-area-afcfta-agreement-mean-for-southafricas-agricultural-sector/.This will, in part, depend on the final rules of origin that are still to be concluded by negotiators. In the same scenario, however, local producers of primary products could be adversely affected if they find themselves competing with more imports. Ensuring these factors are balanced will be critical for the overall success of the AfCFTA in South Africa and other states parties.

The South African government views the AfCFTA in a positive light, labelling it as ‘The dream of our forefathers coming to light’.17Phumla Williams, ‘AfCFTA: The Dream of Our Founding Fathers Coming to Life’, South African Government (blog), July 19, 2019, https://www.gov.za/blog/afcfta-dream-our-founding-fathers-coming-life.It emphasises the objectives of the Agreement to reduce the challenges to trade on the continent and create economic opportunities, calling on South Africans to encourage the spirit of entrepreneurship and embrace the opportunity this continental market of goods and services will provide.18Phumla Williams, ‘AfCFTA: The Dream of Our Founding Fathers Coming to Life’, https://www.gov.za/blog/afcfta-dream-our-founding-fathers-coming-life.There is no doubt that the AfCFTA will be a feature of trade policy in the decade ahead. What remains to be seen is if the AU member states can move out of a pattern that has seen them overpromising and then failing to deliver on such integration initiatives in the past.

The COVID-19 crisis has provided an opportunity for African countries to not only recommit to the AfCFTA but to ensure that it is structured in a way that responds to emerging trade issues. Once the agreement is in operation for trade in goods, negotiators need to turn their attention to the pressing matters of trade in services, electronic commerce and trade facilitation. Phase 2 of the AfCFTA is already set to include the design of rules on competition policy, investment and intellectual property. These will be critical to ensure that a business climate that supports innovation and industrialisation is created.

The AfCFTA also has the potential to overtake other regional trade initiatives on the continent. Existing arrangements, such as SADC, will continue to apply in relation to commitments already in place but the AfCFTA may move to become a truly continentwide single agreement in the coming decade. For example, SADC is yet to tackle issues such as electronic commerce, which is on the agenda for the AfCFTA in the third phase of negotiations. There is no doubt that SADC will remain a critical market for South African exporters and it would be worthwhile to continue to pursue key issues, including trade facilitation, the removal of non-tariff barriers and the development of network infrastructure to support economic activity.

World Trade Organization

The WTO can be described as a mechanism for international globalisation, some would even go so far as to describe it as a ‘Pillar for Global Order’.19Chiedu Osakwe, ‘Future of the Multilateral Trading System: Why the WTO Remains Indispensable?’, Asian Journal of WTO & International Health and Law Policy 10, no. 1 (2015): 1 – 25.It has, however, been under threat for a number of years as it has failed to complete the last round of negotiations under the Doha Development Agenda, initiated in 2001. The WTO has made slow progress on a work plan that includes a range of issues, such as fisheries subsidies. Its last notable success was the Trade Facilitation Agreement that entered into force in February 2017. The start of this decade saw the dispute resolution mechanism of the organisation become inoperable due to the inability of the membership to break a deadlock over appointments to the Appellate Body.

South Africa’s position at the WTO has been based on the premise that the Doha Development Agenda must be concluded in order to meet the concerns of developing countries.20South African Government, ‘South Africa Participates at 11th World Trade Organisation Ministerial Conference , 10 to 13 Dec’, press release, December 9, 2017, https://www.gov.za/speeches/south-africa-participates-at11th-world-trade-organisation-ministerialconference-10-t0-13.The Doha Round began in 2001 at a different time, when the Internet barely existed and economic power was firmly based in traditional markets, such as the US and the EU. It concerns itself with an agenda that was developed to deal with 20th century trade issues. As a result, advances in international trade regulation have happened outside of the ambit of the WTO. Most countries have entered into bilateral or regional agreements to secure their markets and regulate trade with each other. South Africa is no exception, as illustrated above in the context of the AfCFTA.

Questions about the state of international cooperation, including at the WTO, have been magnified by COVID-19. Now is the time for South Africa to update its position within the multilateral trading system. Interconnectivity between states is not going away any time soon and the WTO provides a guarantee of trust among member states that is important for ensuring the confidence needed to restore world trade flows.21Alan Wolff, ‘The WTO and the Future of the Global Trading System’, Address given at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington D.C., October 15, 2018, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news18_e/ddgra_15oct18_e.htm.The WTO serves as the foundation of most bilateral and regional trade agreements, including the AfCFTA.22Alan Wolff, ‘The WTO and the Future of the Global Trading System’.It ensures non-discrimination and transparency on a scale that cannot be replicated by other trade agreements.23Alan Wolff, ‘The WTO and the Future of the Global Trading System’.There are still over 20 nations wanting to join the WTO, and no member has left.24Alan Wolff, ‘The WTO and the Future of the Global Trading System’

South Africa has the potential to play a role in ensuring that the multilateral trading system remains intact. This does not mean that the WTO should not go unchanged. It should be more reflective of the interests of the majority of members from the developing world, the economic power shifts that have taken place over the last two decades and new ways of doing business. It must become more representative and transparent in its decision-making processes. South Africa needs to break its hold on the Doha Round and accept that it is time to work strategically with different partners across geographical and development lines to redesign the WTO. This will require being open to new ways of negotiating and reaching agreement as well as reconsidering the scope of the WTO with regard to trade-related issues traditionally not on its agenda, including investment and environmental concerns.

Diversifying trading partners

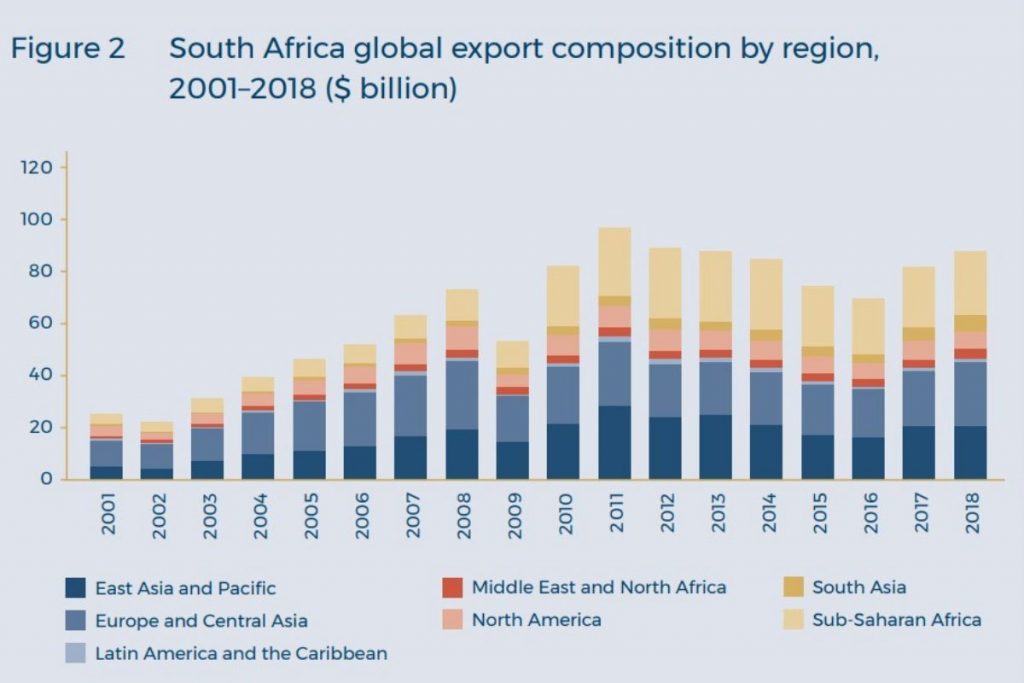

While there is no doubt that the 2020s will be dominated by South Africa’s trading partnerships with other African countries, there is space to diversify and strengthen other partnerships. Over the previous decade, China, the EU, the US, India and Japan were consistently in the top 10 trading partners for South Africa (see Figure 2). These markets will continue to be important as the country pulls itself out of recession and seeks to create more jobs as well as address the persistent challenges of inequality. It is possible that the trading environment will become more protectionist in many of these markets, as the world continues to grapple with the pandemic and states employ trade tools to ensure food security and domestic production of other essential items, such as medical devices. South Africa currently trades with most of these countries under the rules and commitments set by their membership of the WTO, the exceptions being the US and the EU. In the past this would have been a guarantee of stability but this may not be the case as anti-WTO sentiment builds in nations such as the US.

There is little doubt that South Africa’s preferential market access to the US market for some exports will shift during this decade. It is currently made available under a unilateral scheme set out in the African Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA) and the US General System of Preferences. AGOA is due to expire by 2025 and the US has already indicated its intention to seek reciprocal trade arrangements with African countries, commencing negotiations of a bilateral free trade agreement with Kenya in early 2020. South Africa, and its SACU partners, will need to make a decision on whether it wants to attempt another negotiation with the US.25The US and SACU launched negotiations towards a free trade agreement in 2003 but an agreement was not reached. The result was a cooperative arrangement under the Trade, Investment and Development Cooperation Agreement (TIDCA) signed in 2008.This will not be a straight forward process as the benefits for some export sectors will have to be weighed up against perceived risks, such as increased competition for local firms and requests by the US for regulatory reform in various areas, such as intellectual property rights and investment. Without prejudging the outcome, the process should begin sooner rather than later, involve all stakeholders and be based on evidence of the nature of the economic relationship with the US.

South Africa already has in place a trade agreement with the EU as a member of the SADC-EU Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). It currently covers trade in goods and has supported South Africa’s participation in a number of GVCs, such as automotives. The 2020s will be a test for the resilience of this relationship in times of global uncertainty. The post-COVID 19 environment presents opportunities to explore new ways of cooperation among these traditional partners, including ways to expand the EPA’s coverage to services, investment and e-commerce, and to achieve the EPA’s objectives on the transfer of technology, sustainable development and regional integration. An African-wide trade agreement with the EU, in light of the AfCFTA, has been proposed in this regard; however, it is unlikely that this will progress quickly.

To conclude, this brief analysis of South Africa’s trade policy in the coming decade would not be complete without mention of its relationship with Asia. The growing trade and investment ties between the African and Asian continents was one of the distinguishing characteristics of the past two decades. It is reflected not only in terms of trade in goods but other areas such as tourism, infrastructure development and support for continental institutions. This commercial partnership has largely emerged organically under high-level political arrangements (including the BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa), FOCAC (the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation), TICAD (the Tokyo International Conference on African Development) and the India-Africa Forum Summit) that include commitments to cooperation but no specific legal trading arrangements. There has not been an appetite to date to enter into bilateral trade negotiations with partners in Asia but this may change, especially as we see progress being made on important regional initiatives such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. If South Africa wants to continue to diversify its trading partnerships in global growth zones like Asia, and its export basket towards more value-added products, then its trade policy needs to keep pace. The 2020s present an opportunity to update our thinking and see this reflected in a new Trade Policy Strategic Framework that captures the complexity of trade in this new decade.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA would like to thank the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their generous support of this work.