Key to this retreat was brainstorming and deliberation around Agenda 2063: A shared Strategic Framework for Inclusive Growth and Sustainable Development, a document developed by the AU Commission, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Development Bank. The urgency behind the deliberations on Agenda 2063 was with a view to its refinement before discussion at the 22nd session of the AU Assembly and final adoption at the 23rd ordinary session of the Assembly in June/July 2014.

From its conception, to the upcoming adoption of Agenda 2063 at the Assembly in June/July 2014, it will have taken the AU, its partners and citizens (through a web-based consultation process) a mere 13 months before Agenda 2063 becomes an anchor for the work of the AU.

Refinement of Agenda 2063 is crucial to projecting a different African future. However, the congested agenda before the Assembly of Heads of State begs the question as to whether the AU is not stretching itself far too widely, instead of focusing in depth on the issues presented before the Summit. More importantly, what sound inputs can emerge when leaders rush through strategic documents on the work of the AU alongside other pressing issues? How effective has the debate been in member states around Agenda 2063? At a minimum, did national parliaments debate the content of what ought to form the body of such a document?

While Agenda 2063 takes a long-term perspective of where Africa should be by the time the continent celebrates its diamond jubilee, it was a subject of debate alongside a whole list of equally urgent agenda items. The 22nd session of the Assembly, which took place in January this year, marked the 10th anniversary of the adoption of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme, which in principle was the mainstay of the Summit. It is for this reason the Summit took place under the theme of ‘Agriculture and Food Security’. In addition to this crucial theme, which speaks to one of Africa’s most urgent challenges, food insecurity, a host of other pressing items also served before the Assembly.

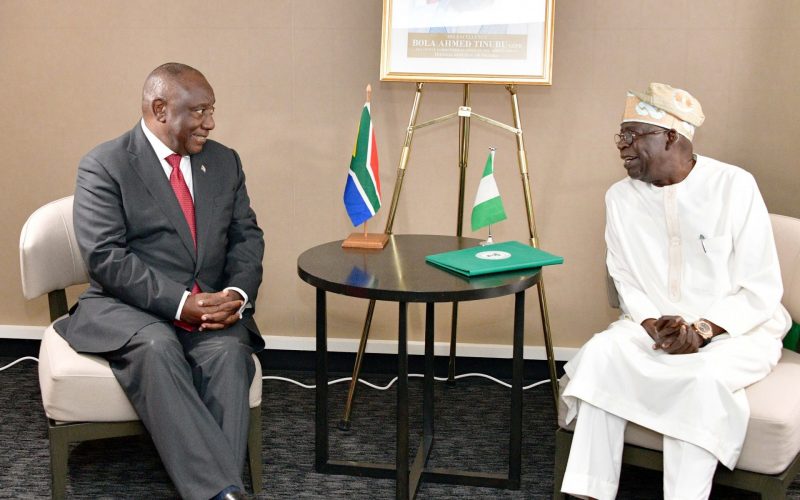

First, the AU adopted the reports of high-level committees on the Assessment of the African Standby Force and the Operationalisation of the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises. Second, the Assembly adopted reports of high-level committees on United Nations Reforms and the post-2015 Development Agenda, including an African common position in that regard. Third, reports on the Bali round of trade negotiations and the Warsaw COP19 were presented to the Summit. Fourth, the Summit also dealt with the recommendation to expand the powers of the African Court for People’s and Human Rights. Moreover, the African Union Peace and Security Council also saw the election of new members, including Namibia and South Africa from Southern Africa. Ordinarily, these issues would deserve deeper scrutiny in their own right at the Summit.

But if the Summit was supposed to deliberate in depth on issues of agriculture and food security, this conversation did not really take place. It was instead hijacked by security challenges in the Central African Republic and South Sudan. Certainly, it is not odd for the Summit to be preoocupied with pressing peace and security challenges on the continent. These are crucial items for debate as their impact on the livelihoods of Africans across conflict-ridden regions is immediate and the long-term consequences of such conflicts on development are real. However, with the agenda of the AU becoming more congested during peak hours when leaders converge for the January and June/July summits every year, the Commission should start to think about innovative ways of streamlining the agenda in order to allow for better and targeted inputs from visiting delegations.

Increasingly, the work of the AU is becoming of relevance to the national policy contexts of member states. Therefore, and in light of the widening of the agenda, the increasing the frequency with which the Assembly should meet is potentially worth considering in order to ease the burden on the two Summits that take place each year. Member states, in addition to strengthening their own delegations to the African Union, should also strengthen the capabilities and decision-making processes of the Commission.

Moreover, in order to give practical expression to Regional Economic Communities (RECs) as building blocks in continental integration, the neglected liaison offices of RECs in Addis Ababa should be upgraded, provided with proper human and physical infrastructure, and formally integrated into the work of the Permanent Representatives’ Committee.

The AU is becoming a more complex operation with impact on regional and national contexts. Going forward, its processes should be better prepared and geared toward greater efficiency, with a possible increase in summits for improved accountability, including better agenda coordination and management.

It is not too late for national parliaments to engage with the AU Vision 2063 and to make their voices heard on the implications for citizens on the African continent.