Recommendations

- African policymakers need to invest in social protection policies and integrate this into their national climate responses in order to build the resilience of poor populations that are most vulnerable to climate change.

- All AU member states should sign the Establishment Agreement of the Africa Risk Capacity Insurance Company to enable the company to provide continental risk pooling for extreme weather events.

- Lesson sharing and knowledge exchange on established social protection policies should be promoted to help neighbours leapfrog implementation processes.

- Policymakers must leverage new financing mechanisms such as the Loss and Damage Fund and Green Climate Fund to finance social protection pilot programmes on the continent.

Executive summary

Climate change will push more than 130 million people into poverty if there are not sustained efforts to reduce carbon emissions and implement climate adaptation plans. It presents a major threat to the realisation of the AU ambition for each member state to attain at least middle-income status by 2063. Africa’s first continental climate strategy, the AU Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan (2022–2032), aims to preserve livelihoods amid climate change through a people-centred approach to climate action. Guided by this approach, the strategy identifies social protection as a way to strengthen the capacity of vulnerable states to protect against loss and damage and build resilience.

Social protection is not a new policy response to crisis – the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic saw the near-global dispersion of emergency funds to support citizens. Social protection’s ability to address poverty and inequality also enables it to help those populations most affected by climate change to recover from disaster.

Introduction

Climate change is often described as a ‘risk multiplier’, given its capacity to undermine resilience and exacerbate poverty and inequality. For Africa this is particularly relevant, as the region is home to the largest share of people living in poverty.1Samuel Kofi Tetteh Baah et al., “Where in the World Do the Poor Live? It Depends How Poverty is Defined”, World Bank, August 2, 2023.

When confronted with the COVID-19 pandemic, the continent saw a reversal of the development gains of the 2010s and, by 2020, half a billion people in sub-Saharan Africa were classified as extremely poor2According to the World Bank (World Bank, “Understanding Poverty: Nowcast of Extreme Poverty, 2015–2022”), extreme poverty is measured as the number of people living on less than $1.90 per day. for the first time. Climate change compounds these threats to development. The continent experiences high rates of climate change vulnerability and an exceptionally low resilience to the impacts of climate change, according to results from the Climate Change and Economic Vulnerability, and Climate Change and Economic Resilience indices.3Joseph Upile Matola, “Measuring Economic Vulnerability and Resilience to Climate Change” CoMPRA 29, South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburg, February 16, 2024). In reviewing Africa’s post-pandemic economic recovery, it would seem that African policymakers largely failed to incorporate climate-resilient policies to safeguard their fragile economies against future shocks.4Joseph Upile Matola, “Africa’s COVID-19 Response: A Wasted Opportunity” (CoMPRA 21, SAIIA, Johannesburg, August 21, 2023). Because of Africa’s heightened vulnerability to climate change, climate shocks are economic shocks and, thus, economic policymaking in Africa requires climate-proofing.5Think20 India, “Beyond Mitigation: How Climate Resilience Needs to Bridge Gap between Solutions & Implementation”, YouTube, August 7, 2023. Social protection, mainly in the form of cash or in-kind transfers, was widely implemented at the onset of the pandemic. Between February and December 2020, 209 countries announced social protection measures in response to the pandemic.6Of the 222 countries and territories studied by the ILO Social Protection Monitor, 209 announced a social protection measure in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. See International Labour Organization, “Social Protection Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis Around the World”, December 31, 2020. Of the new measures announced, 53% were entirely new programmes and, of these, the overwhelming majority (90%) were non-contributory.7ILO, “Social Protection Responses”. These measures allowed governments to disburse aid quickly to their populations to mitigate the economic impact of the health emergency.

As the continent strives to build its adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change, this kind of rapid protection against the fallout of disasters should be employed with climate-induced loss and damage. The latter is a significant threat to Africa’s economic growth and development and the livelihoods of its most vulnerable populations.

Social protection

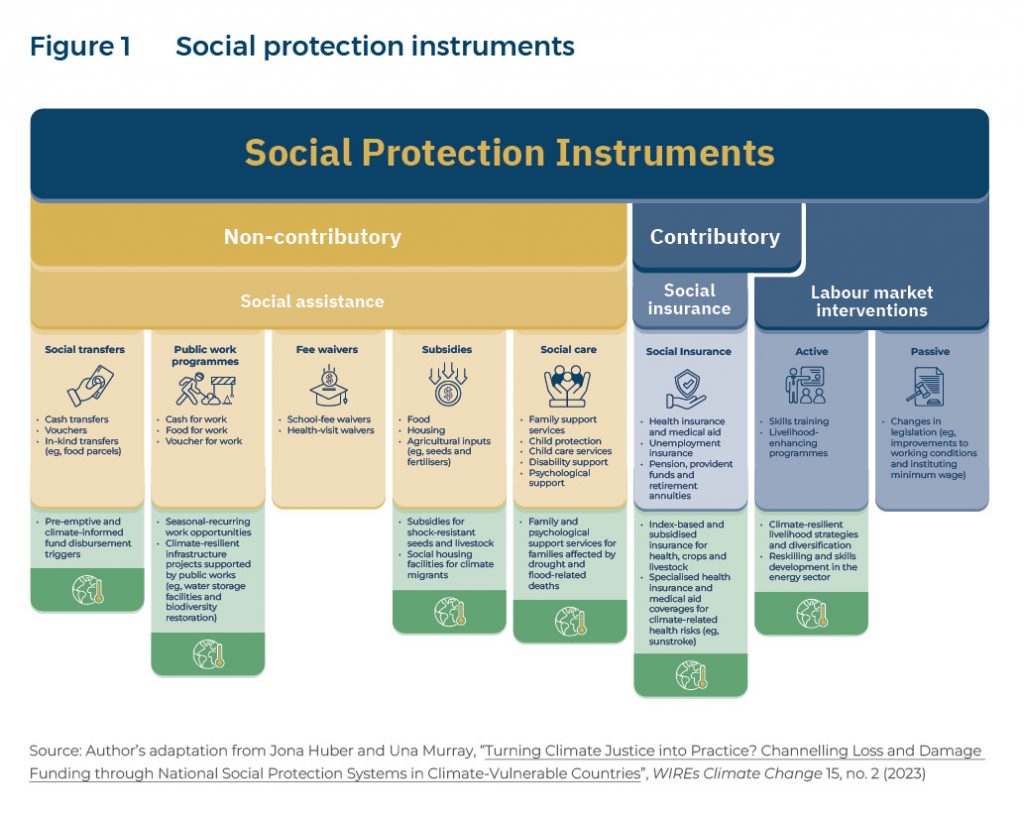

Social protection is defined by the International Labour Organization as a mix of policies that aim to reduce poverty and inequality. Social protection is divided into three main forms: non-contributory social assistance (including cash transfers or food parcels), contributory social insurance (including unemployment insurance) and labour-market interventions such as skills development. Such policies have received increasing attention as an approach to building resilience against climate change.8Arun Agrawal et al., “Climate Resilience Through Social Protection” (Background Paper, Global Commission on Adaptation, Rotterdam and Washington DC, August 23, 2019).

The utility of social protection lies in its ability to be used pre-emptively (before a climate or economic shock) to improve resilience and as a countermeasure to lessen the harmful impacts of crises during and after their occurrence, as seen with the COVID-19 pandemic. Social protection policies can also strengthen the capacity of states to protect their populations from the economic impacts of climate disasters. In addition, they can be used to protect at-risk populations by supporting their adaptation efforts and to help those negatively impacted by green transition policies to meet carbon emission reduction targets.

Social protection is not well understood as a policy mechanism for advancing climate action and its impact on poverty and development remains controversial. Despite this, it has been shown to support vulnerable households in coping with climate disasters, although its primary objective is typically to address poverty and inequality. Contributory climate-responsive social protection includes weather-based index insurance, while non- contributory income support takes the form of cash transfers and in-kind food parcels distributed during a climate disaster (see Figure 1). These measures reduce people’s need to take on harmful coping strategies such as selling off livestock and agricultural stores, removing children from school to work and taking on high-interest loans. Social protection instead encourages saving and investment in better fertilisers and seeds.9Teresa Anderson, Avoiding the Poverty Spiral: Social Protection to Address Climate-Induced Loss and Damage, Report (Johannesburg: Action Aid, 2021). Just under half of the global population is covered by at least one social protection benefit yet, in Africa, coverage is less than 17.4%.10ILO, “World Social Protection Data Dashboards”, 2021.

Climate-responsive social protection tools

Climate-proofing policy for Africa is crucial, as climate change remains the pre-eminent threat to the continent’s development. Achieving resilience is a complex activity, requiring AU member states to consider a plethora of risks on top of their climate concerns.

Considering climate change in policymaking extends to social protection. Some actors on the continent offer important lessons for their neighbours in climate-proofing social policy.

Climate risk insurance

As a contributory form of social protection, weather-based index insurance protects against adverse weather retrospectively, after poor crop yields. A contract is written against a weather index based on a historical relationship in a particular region between drought and crop failure. This is extendable to cattle farming. Farmers are able to collect immediate compensation if the index reaches a certain point or ‘trigger’, such as a specific number of days without rain. Insured farmers no longer have to adopt negative coping strategies such as selling their productive assets to make ends meet during times of crisis. Insured farmers are also more credit worthy, which promotes their investments in higher risk and higher yield crops.11Mariya Aleksandrova and Yu Lu, “Weather Index Insurance: Promise and Challenges of Promoting Social and Ecological Resilience to Climate Change” (Briefing Paper 14/2021, Deutsches Institut fur Entwicklungspolitik, Bonn, 2021).

The African Risk Capacity (ARC) is a specialised agency of the AU. The ARC is mandated to help AU member states prepare better for extreme climate disasters and disease outbreaks. Currently, 30 countries have joined the sovereign-level index insurance body ARC Insurance Company Limited (ARC Ltd).12Germany, Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Insurance Policies Against Drought Effects: ARC and ARC Replica”, September 20, 2022. As an entity of the ARC, ARC Ltd offers risk-transfer services to AU member states through risk pooling and reinsurance. Diversification of drought- related losses has shown a 50% reduction in the contingent funds for drought response. African Risk Capacity Project Team, “Note for Experts’ Consultation: African Risk Capacity – A Pan-African Disaster Risk Pool”, UN Climate Change, May 2011.[/fn] Three governments in the Sahel received payouts totaling $26.3 million from ARC Ltd in 2014 following poor rainfall, which helped 1.3 million people affected by drought.13Joanna Syroka and Esther Baur Reinecke, “Weather Index Insurance and Transforming Agriculture in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities” (Background Paper, African Development Bank, Dakar, 2015). ARC Ltd has disbursed $125 million since its inception in 2014, but remains dependent on donor funding.14Akankshita Mukhopadhyay, “ARC Sets New Record with $60m Payout in 2022, Pioneering Climate Resilience in Africa”, Reinsurance News, September 12, 2023. Only 39 AU member states have signed the ARC Establishment Agreement, limiting the company’s ability to pool risk and provide rapid and predictable financing to countries in need. Improving the risk pooling and strengthening the continent’s resilience to climate shocks require complete buy-in from AU member states.

Contributory measures such as those provided by ARC Ltd tend to be financially unattainable for individuals. Especially for the poor, building resilience through social protection requires both contributory and non-contributory mechanisms.

Non-contributory or in-kind transfers

Cash and in-kind transfers have a demonstrated history of directly addressing poverty among the most vulnerable. Cash transfers are predictable sources of income, while in-kind transfers take the form of food parcel donations and the provision of seeds and fertilisers. In the AU’s climate strategy, social transfers are highlighted and the AU recommends these be made predictable to protect livelihoods and promote livelihood diversification.15AU, African Union Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan (2022–2032) (Addis Ababa: AU, June 28, 2022), 62.

Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) is a prime example of climate-resilient social protection, although it was not intended as a response to climate disasters.

Implemented with international assistance, the PSNP was designed to address Ethiopia’s protracted food security crisis, which stems from multiple prolonged droughts.16Rachel Sabates-Wheeler et al., “Expanding Social Protection Coverage with Humanitarian Aid: Lessons on Targeting and Transfer Values from Ethiopia”, The Journal of Development Studies 58 (July 19, 2022): 1–20. The droughts over the past three years have reduced Ethiopia’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 1–4% and climate change will lead to a 10% GDP reduction by 2045.17World Bank Group, Climate Risk Country Profile: Ethiopia (Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2020), 10. Most PSNP recipients have natural resource-based livelihoods that are at risk from drought. Through the PSNP, they receive either cash or food in exchange for participating in public works programmes to build and maintain water and soil conservation projects, community roads and educational infrastructure.18Productive Safety Net Programme in Ethiopia: Multi Donor Trust Fund for Ethiopia Households without physically fit members receive cash or food directly. The programme targets highly food-insecure and vulnerable agriculture-dependent communities during the dry season. The PSNP has supported 10 million beneficiaries and is one of the most extensive social protection programmes on the continent, second only to that of South Africa, where 18 million children, elderly and disabled persons are monthly social transfer beneficiaries.19Leila Patel, “Social Protection in Africa: Beyond Safety Nets?”, Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 45, no. 4 (2018): 88. South Africa’s own climate- responsive public works programme has seen some positive impacts on biodiversity in the Eastern Cape, but on a smaller scale.20Government of South Africa, Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment, “National Climate Change Response: White Paper” (Pretoria: Government Printer, 2014).

Besides providing recipients with predictable food or income sources, the separate pilot programme PSNP Plus played a key role in building the resilience capacity of vulnerable communities in Ethiopia. It aimed to improve communities’ capacity in water management, crop production and post-harvest handling, with the overarching objective being to see participants ‘graduate’ from the PSNP. Lesson sharing and knowledge exchange would enable governments to leapfrog and implement climate-sensitive social assistance programmes.

Financing resilience: Social protection from loss and damage

While the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has strived to address climate mitigation and adaptation, loss and damage remain inadequately financed, researched and incorporated into global climate commitments. ‘Loss and damage’ refers to the impacts of climate change that have not been avoided successfully through mitigation

and adaptation measures, and is considered the third pillar of climate change.21Andrew Gilder and Olivia Rumble, “An African Perspective on Loss and Damage” (Policy Insights 130, SAIIA, Johannesburg, 2022), 2 The African Development Bank predicts Africa will need $290–440 billion between 2020 and 2030 to cover the economic damages of climate change.22Zero Carbon Analytics, “Loss and Damage Funding for Africa Will be Back on the Table at COP28” (Briefing, Zero Carbon Analytics, November 15, 2023). Africans are heavily reliant on agriculture, with as many as 70% depending on subsistence and commercial farming and fishing alone.23Mamadou Biteye, “70% of Africans Make a Living Through Agriculture, and Technology Could Trnasform Their World”, World Economic Forum, May 6, 2016. Sub-Saharan Africa’s agriculture is highly dependent on rain but, as weather patterns become more unpredictable, drought has been highlighted by the African Group of Negotiators as the most prevalent climate disaster facing the continent.24Heinrich Boll Stiftung, “Unpacking Finance for Loss and Damage: Why Do Developing Need Support for Loss and Damage?” (HBS, Washington DC), 4.

Loss and damage can manifest in sudden-onset climate disasters such as flash floods and cyclones and in slow-onset climate disasters such as desertification and the salination of water resources. The last two UNFCCC Conference of the Parties summits in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) brought global attention to the issue of loss and damage. In Egypt, loss and damage was for the first time recognised as a stand-alone agenda item for negotiations and in Dubai, the Loss and Damage Fund was launched and received its first donations, totaling just under $800 million. The operationalisation of the fund included a call for enhanced support for adaptive social protection. In addition, the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience (the new operational framework for the Global Goal on Adaptation) promotes adaptive social protection as one of the resilience tools to reduce the impact of climate change on poverty.25“Adaptive social protection” aims to link social protection, climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. See Mark Davies et al., “‘Adaptive Social Protection’: gies for Poverty Reduction”, IDS Bulletin 39, no. 4 (September 4, 2008).

The chief challenge in realising more comprehensive and climate-sensitive social protection systems in Africa is the lack of appropriate finance. Taxation typically funds national social security systems where they are not supported by international aid. For instance, Ethiopia’s PSNP is funded by a consortium of development partners, including the World Bank. While the Ethiopian government aims to cover a third of the $2.2 billion needed to fund the fifth iteration of the programme by 2025, it was only able to fund only 14% from 2015–2020.26UK Government, Department for International Development, “Ethiopia Productive Safety Net Programme phase 4 (PSNP 4)” (London: DFID, 2015). While the continent’s population growth could peak at close to 2.5 billion by 2050, tapping into this ‘population dividend’ requires proportionate economic growth. New and existing industries would need to expand to accommodate Africa’s young workforce and to take advantage of the economic opportunities of the African Continental Free Trade agreement.

The Global Environment Facility Trust Fund (GEF) has provided financial support to innovative investments that link climate action to social protection. The $10 million Namibian Integrated Landscape Approach for Enhancing Livelihoods and Environmental Governance to Eradicate Poverty sought to reverse the environmental degradation that threatens the livelihoods of some of its poorest citizens through landscape management. This included a pilot public works programme to restore 10 000ha of forested land.27Government of Namibia, Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, “Namibia Integrated Landscape Approach for Enhancing Livelihoods and Environmental Governance to Eradicate Poverty (NILALEG) Project”, https://www.meft.gov.na/ projects/nilaleg-project/313/.

The objectives of multilateral climate funds largely align with the aims of social protection initiatives, namely to protect the most vulnerable communities from further harm and to advance the achievement of national, regional and global development goals.28Mariya Aleksandrova et al., “Unlocking Climate Finance for Social Protection: An Analysis of the Green Climate Fund”, Climate Policy (April 7, 2024). These funds, including the GEF, Green Climate Fund and the new Loss and Damage Fund for Developing Countries, should be leveraged to strengthen social protection systems on the continent. They have the potential to become core financing institutions for social protection for AU members.

Conclusion

In 2022 alone, climate change led to more than $8.5 billion in losses and damage across Africa, affecting more than 110 million people.30 Funding social protection systems is a core element of building the continent’s climate resilience.

For Africa’s decisionmakers, considering all policy options for improving resilience to climate change is non-negotiable. Case studies from Ethiopia and elsewhere on the continent provide important lessons on climate-proofing policies to protect the poor and the climate-vulnerable through climate-sensitive social protection. This aligns with the AU’s commitment to a people-centred climate strategy that can protect development gains against future shocks.