Recommendations

- Enhanced ambition is needed for climate emissions and adaptation pledges to be in line with requirements to achieve a climate-resilient, zero-carbon world by mid-century.

- NDCs must directly correspond with and support country visions towards net-zero emissions trajectories by 2050.

- COVID-19 green recovery measures and plans must be aligned with NDCs and LTSs. In addition, climate finance should be aligned with green recovery finance.

- Long-term plans should be supported by national climate legislation.

Executive summary

The global COVID-19 pandemic has marked a turning point in business-as-usual practices, highlighting the need to re-think and re-establish economy-wide norms based on systemic sustainability and equity considerations. At the same time, countries are attempting to develop and implement their short- and longer-term policy planning instruments for climate change – Nationally Determined Contributions and Long-term Low Emissions Strategies – to move towards zero-carbon, climate-resilient futures. In the development of these strategies, countries are making important choices about immediate and longterm pathways to drive the transition to carbon neutrality and climate adaptation. If transformational and ambitious, these climate policies and planning tools can position countries to contribute to a global response to climate change, as well as strategically situating them to take advantage of post-COVID-19 green growth opportunities.

The 26th Conference of Parties meeting of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP26) will take place in November 2021 in Glasgow. It is set to address some of the most pressing challenges in the transition to resilient, carbon-neutral societies. Five years after the signing of the Paris Agreement, countries are yet to reach the adaptation and mitigation requirements prescribed by science, underscoring the need for greater urgency. This briefing highlights key policy processes needed for Africa to support longerterm transformation, as well as the importance of aligning COVID-19 recovery efforts with mid-century climate-resilient visions.

Policy processes to support long-term transformational change1While this paper focuses on NDCs and LTSs, many other country-level climate strategies are equally important, such as Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions, National Adaptation Programmes of Action, National Climate Change Strategies, Climate Bills and Green Economy Strategies (or other formal sectoral policies/strategies).

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) form the backbone of the Paris Agreement. NDCs are policy tools that describe each country’s self-determined plans to curb carbon emissions and enhance resilience until 2030, typically articulated in terms of five- or 10- year target periods. In 2015, 186 nations submitted their first round of NDCs to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).2International Institute for Sustainable Development, “Climate Ambition Summit 2020”, Earth Negotiations Bulletin, December 12, 2020.In 2020 the second round of submissions was due to take place, but COVID-19 disrupted and delayed these processes. Most countries have recently submitted their revised NDCs or are working towards submitting them before COP26. In addition to the NDCs, the Paris Agreement calls on all countries to formulate long-term, low-carbon emissions development strategies by 2020 (also known as Long-term Strategies [LTSs]). These long-term planning instruments take a whole-of-society approach to finalising a net-zero roadmap. By December 2020, 28 countries had submitted their LTSs to the UNFCCC.

NDC commitments are increasingly being linked with longer-term goals to achieve carbon neutrality. NDCs are the iterative building blocks towards longer-term futures – ensuring that planners and policymakers are aligned with a common desired future. From the outset, it is imperative that countries have a long-term vision that all sectors and parts of society buy in to.

It is also crucial that countries’ interim goals, or medium-term commitments, are compatible with these longer-term goals. If not, countries will need to consider ramping up their commitments significantly in 2021, meaning a much earlier peaking date for emissions than 2030 and aggressive phase-out policies on fossil fuels.

Gathering momentum towards COP26

To date, countries have varied in their aspirational commitments and the pathways to achieve their carbon reductions. Pakistan, for example, has announced the cancelation of plans to develop new coal power plants, while India intends to double its renewable energy target. The UK has committed to a 68% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions below 1990 levels by 2030, while the EU has pledged to reduce GHG emissions by 55% over the same period. The EU’s pledge falls within the broader EU Green Deal – a multipronged systems approach to revive the post-pandemic economy through a combination of regulation, investment and carbon pricing. In the coming months, Brussels is also set to introduce the legislation required to support implementation of the Green Deal

The US has committed to 100% clean electricity by 2035 through technological advances in green hydrogen power, batteries, and carbon capture and storage, while China has pledged carbon neutrality by 2060, sending a signal to domestic industries and local governments to guide research and investment. Even though the Chinese government will no longer approve new coal-burning power plants, more than 100 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity is already in the pipeline and relatively young coal generation assets remain a critical risk. Given this, critics are concerned that China’s medium-term commitments are not ambitious enough to meet its 2060 vision.

In Africa, countries are in the process of revising their NDCs and developing LTSs. South Africa has shown leadership with its recently revised NDC (to 2030),3South Africa, Department of Fisheries, Forestry and Environment, “South Africa’s Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) Launched”, March 30, 2021.as well as its Low Emissions Development Strategy 2050.4South Africa, Department of Fisheries, Forestry and Environment, South Africa’s Low Emissions Development Strategy 2050, February 2020.It has also submitted a national adaptation strategy and a new draft Climate Change Act, and has set up governance systems to approach a country-wide green growth vision through an inter-ministerial Presidential Climate Change Commission. This commission held its inaugural meeting in February 2020. Non-governmental stakeholders, such as civil society organisations and environmental advocacy groups, are also represented on it.

Rwanda has demonstrated leadership with the submission (in March 2020) of its revised NDC, laying out the details of its pathway towards a green transition. The combined contribution is a 38% reduction in GHG emissions compared to business as usual in 2030. Rwanda has estimated the total cost of implementing its NDC at $11 billion. It is also in the process of drafting its long-term Green Growth and Climate Resilience Strategy to 2050.

In addition, subnational actors, cities, philanthropists and business leaders have also made pledges towards carbon neutrality. This includes the Race-to-Zero campaign, which is a coalition of leading decarbonisation initiatives, representing 708 cities, 23 regions, 2 162 businesses, 127 investors and 571 higher education institutions. There have also been mitigation pledges from companies and industry bodies. Among others, Repsol, a Spanish energy company, announced in 2019 that it would achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. In tandem with this, it announced an immediate €4.8 billion ($ 5.85 billion) impairment of its asset values.5Repsol Global, “Repsol Will Be a Net Zero Emissions Company by 2050”, Press Release, December 2, 2019.Many others are adopting similarly rigorous approaches to identifying interim milestones for 2030, flagging that these commitments will require a root-andbranch transformation of their supply chains and business models.

There has also been discussion around the pathways and choices needed for financial institutions and the financial system more broadly to drive an active transition to a net-zero carbon economy. The European Investment Bank, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), among others, are making headway on long-term goals. The IMF is also incorporating climate risks into its annual review of countries’ overall economic and financial stability. Launched in December 2020, the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative supports the goal of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 and is aligning its $37 trillion investment capital accordingly.

Some way to go to raise ambition for what is required by science

Despite increased efforts by countries and non-state actors, the combined impact of climate mitigation and adaptation pledges still falls short of what is required to achieve a climate-resilient, zero-carbon world by mid-century.

In February 2021 the UNFCCC issued a preliminary synthesis report measuring the progress made on NDC submissions to date, based on the UNFCCC NDC registry as of 31 December 2020.6UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, FCCC/PA/CMA/2021/2: Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement – Synthesis Report by the Secretariat (Glasgow: UNFCCC, February 26, 2021).The report synthesises information from 48 new or updated NDCs, representing 75 parties (including the EU bloc of 27 countries) and accounting for approximately 30% of global GHG emissions. It shows that 60% of parties have yet to submit their revised NDCs, including large carbon emitters like India and China.7Both India and China have not updated their NDCs since 2016.It also illustrates that the collective ambition of the NDCs’ mitigation pledges is far from sufficient. The updated NDCs will lead to an estimated reduction in total GHG emission levels by 2030 that is about 3% lower than under the parties’ previous NDCs.8Sergey Kononov, Initial Version of NDC Synthesis Report (Feb.2021): Context and Key Findings (Virtual Presentation, UNFCCC GHG Inventory System Training Workshop, March 3, 2021).Such low reductions fall far short of those recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC has stated that9Please note that these findings are only for the parties that registered on the UNFCCC Registry before 31 December 2020, covering 30% of global emissions. However, they are still indicative and call for further climate action. Besides an increase in action required, more support is also needed for the implementation of such country plans.

emission reduction ranges to meet the 1.5°C temperature goal should decline by about 45 per cent from the 2010 level by 2030, reaching net zero around 2050. For limiting global warming to below 2°C, CO2 emissions need to decrease by about 25 per cent and reach net zero around 2070.

According to Climate Action Tracker,10Climate Action Tracker, “Comparability of Effort”.the scope of revisions and the extent to which they reflect strengthened climate ambition vary per country. Some countries have merely restated their past commitments or made new commitments that do not substantially increase ambition. In other cases, revised NDCs include new commitments to enhance the overall scope of current plans and provide detailed information on sector-specific targets, as well as implementation plans for achieving these targets.

In general, however, the NDCs are clearer and more comprehensive. The quality of information, including the data underpinning parties’ commitments, has also improved significantly. Parties now pay more attention to planning and implementation processes, including the engagement of non-state actors in NDC road maps. Importantly, the adaptation components of NDCs have been strengthened, providing notably more information on vulnerabilities, sectoral actions and contingency measures. In comparison with previous NDCs, this shows increased focus on adaptation planning, including more time-bound quantitative targets, as well as specification of the associated monitoring and evaluation indicators. In many countries, adaptation efforts are being linked with socioeconomic development targets, and more specific synergies between adaptation and mitigation are being highlighted.

Aligning COVID-19 recovery efforts with long-term climate-resilient visions

While COVID-19 has presented the climate world with numerous challenges (most directly, in this case, the postponement of COP26 by a year), it has also generated a conversation about how to reboot the global economy in its aftermath, and how to do so in a sustainable way. It has highlighted the importance of preparing properly for risks of all kinds and the need for broader societal cooperation on achieving medium- and long-term goals. To ‘build back better’, countries are now reconsidering approaches for a transformational shift away from fossil fuel-dependent business-as-usual pathways towards climate-positive actions. The latter include investing in sustainable jobs and businesses, ending bailouts for polluting industries and fossil-fuel subsidies, and integrating climate risks in all financial and policy decisions. Similarly, there is growing interest in using debt swaps or other financial incentives to enhance sustainability while easing debt burdens.

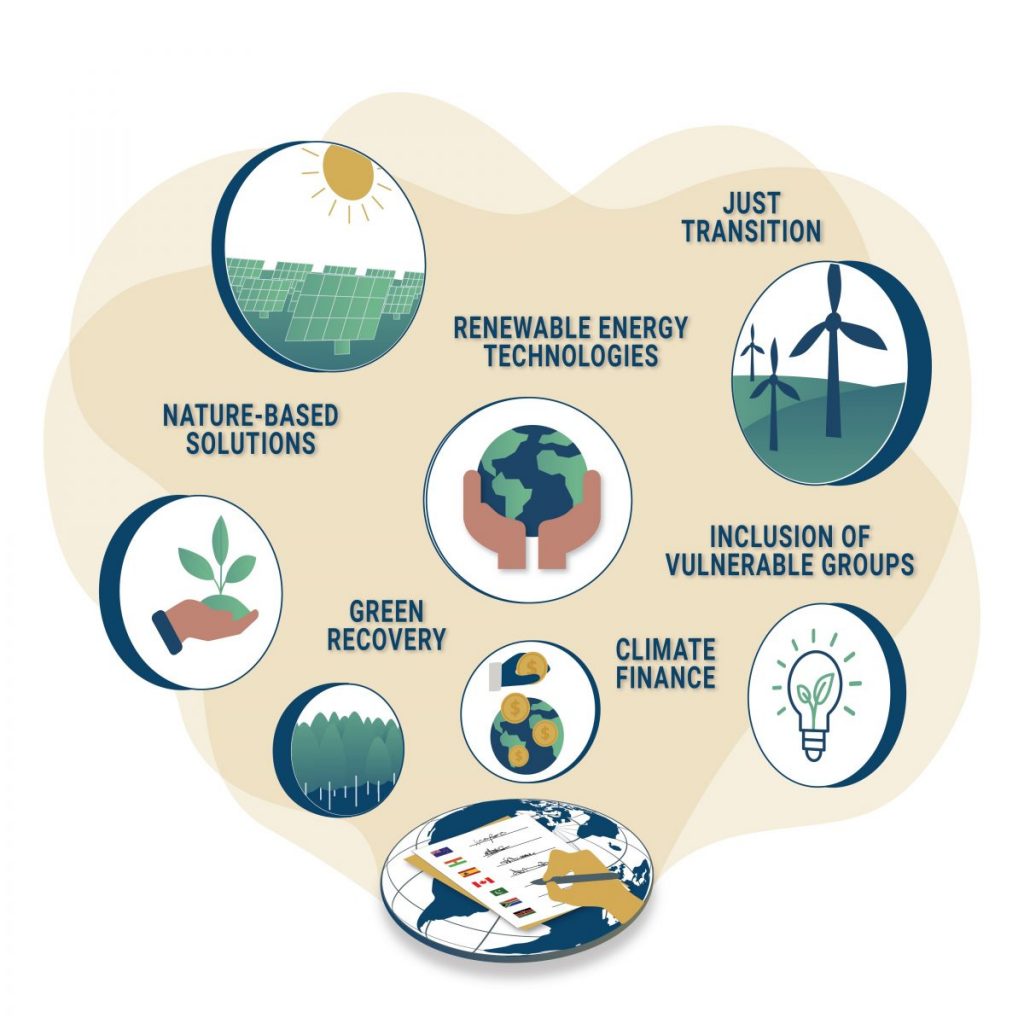

Figure 1: Climate change priority areas must align with countries’ green growth recovery plans and ambitions

These green recovery plans must align with countries’ revised NDCs and the development and strengthening of new LTSs. These long-term pathways, interim goals and timeframes must be mapped out and the details of how to go about achieving these unpacked. Long-term visions need to be in place so that NDCs can build towards longer-term societal goals. Both NDCs and LTSs are living documents that continually need to be revised and strengthened. They should reflect improvements in technology, science and data, demonstrate leadership by increasing mitigation and adaptation commitments, and improve ownership by engaging a broader group of stakeholders around climate commitments.

What agenda items are on the COP26 table?

Figure 2: Pressing issues to be discussed at COP26 in Glasgow

Unlike COP21 in Paris, COP26 does not have a large set of texts to negotiate. However, there are important technical issues to be finalised. Among these are numerous policy and practical solutions that would support a transition to low-cost, just, inclusive and resilient economies. These solutions include the phasing-out of coal; the wide roll-out of electric vehicles; and a move towards mainstreaming climate risks into investment and economic decision-making, adaptation and resilience. In addition, there are the development of policy and regulatory frameworks to attract the private sector to help deliver and finance these investment needs; the transfer of appropriate technologies; and technical assistance to build capacity and data to drive policymaking. Importantly, this includes support to communities in a secure and just transition away from fossil fuels, particularly coal.

Progress on climate finance is the major challenge to climate action in Africa and elsewhere. In 2020 developed countries committed to deliver $100 billion a year in climate finance to vulnerable countries. This has not happened. COP26 will likely set new longterm targets for climate finance beyond 2020 (perhaps to 2025). A considerable amount of climate finance is urgently needed to support NDC implementation and net-zero emissions trajectories. According to Carbon Brief, in the most recent round of NDCs (up to December 2020), a total of $373 billion in international climate financing was requested by developing nations. A large chunk of this is the $236 billion quoted by Ethiopia.11Joss Gabbatiss, “Analysis: Which Countries Met the UN’s 2020 Deadline to Raise ‘Climate Ambition’?”, Carbon Brief, January 8, 2021.South Africa’s revised NDC proposes ambitious and quicker emission cuts,12Terence Creamer, “South Africa’s Draft Climate Pledge Offers Quicker Emissions Cuts, But Seeks Step Rise In Yearly Climate Funding To $8 Billion”, Engineering News, March 30, 2021.but makes these conditional on higher levels of climate finance to support its transition, proposing an increase from $2 billion a year currently to about $8 billion by 2030. Defining the sources and modalities of these financial flows is imperative to unlock country ambition.

For Africa, adequate and fair finance for adaptation and loss and damage is particularly urgent. This includes the rules to operationalise the global goal on adaptation,13Established by the Paris Agreement in 2015, the Global Goal on Adaptation sets out to enhance adaptive capacity and strengthen resilience, with a view to reducing vulnerability and contributing to sustainable development. It requires all parties to engage in and communicate their efforts to plan and implement adaptation.as well as clarity on a new carbon market that could potentially finance adaptation in African countries. The Africa Group of Negotiators is unified on the urgent need to protect nature and safeguard ecosystems to increase mitigation and adaptation benefits, as well as to protect livelihoods. There is hope that COP26 will integrate nature-based solutions (or ecosystem-based adaptation) into the Paris implementation strategy. Progress made at the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, to be convened in October 2021 in China, will pre-empt this discussion. It is crucial to align the climate and biodiversity goals of these two multilateral processes, and to further integrate climate change in a post-2020 global biodiversity framework.

Figure 3: A common climate vision for the continent

Enhanced youth inclusion in climate advocacy is also at the top of the African COP26 agenda. Young people will not only be most impacted by climate change but also inherit the responsibility for addressing it. The question of youth agency is particularly acute in Africa – the region most vulnerable to climate impacts and with the youngest population, with almost 60% under the age of 25.14Alex Benkenstein et al., Youth Climate Advocacy, Special Report (Africa Portal, November 2020).In September 2021, 400 young people from around the world will meet in Italy to discuss elements of the climate negotiation process. This meeting is part of a larger process that started in September 2019 at the New York UN Youth Climate Summit. This coalition of young people includes #Resilient40, a climate network made up of about 70 young leaders from 29 African countries.

Conclusion

Failing to drive significant change across multiple sectors in the next decade holds enormous risk for all countries and all sectors. Remedial action to avert runaway climate change needs to take place with urgency, through iterative and steady support for multiple solutions and technologies in various sectors. These actions and policies should be based on, and aligned with, longer-term, economy-wide commitments towards systemic sustainability and green recovery. COVID-19 has highlighted the need for speedy policy responses to crises (including future climatic, environmental and health shocks), as well as the importance of international and cross-sector collaboration.

There are signs of real momentum as we head towards COP26 in November. Positive global developments have increased the possibility of radical action on climate change: a new US administration, a more active leadership role by China, momentum across the business and investment sector, and opportunities related to green recovery and the introduction of new green stimulus measures. To date, many countries, including some African and other vulnerable developing countries, have pledged to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 or earlier and major players have substantiated their plans by more clearly articulating financing strategies and pathways to implementation. These transformative policy reforms open windows of opportunity for new economic activities, employment and competitive advantages.

COP26 is an important milestone for the urgent implementation of the Paris Agreement. The UK COP presidency will need to manage the geopolitics skilfully and reinforce the overall signal of irreversibility and momentum. A COP decision that underlines the need for strengthened, five-yearly revisions of NDCs could help, as would a global agreement to reach net-zero targets by 2050. What matters in the end is the gap between current pledges and what is needed to put the world on track to limit global warming to 1.5°C below pre-industrial levels. The timing and sequencing of suitable reforms is far from trivial and requires a sound evidence basis and the requisite financing support.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of SIDA for this publication.