Consider the African National Congress (ANC). During the long struggle against apartheid, what the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) saw as a liberation movement, the racist minority government of South Africa labeled as terrorists. Ask one person in Washington and another in Riyadh today about Al Qaeda and you’re bound to get the same diversity of opinion.

But political agendas and legal definitions are two different things, and the distinctions matter. As defined by the OAU, national liberation movements are the organisations that fought for freedom from colonialism or apartheid: Swapo in Namibia; the MPLA in Angola; Frelimo in Mozambique; Zanu and Zapu in Zimbabwe; Kanu in Kenya; and the ANC. Armed oppositions that fought against their own repressive regimes – such as Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front – do not meet this definition.

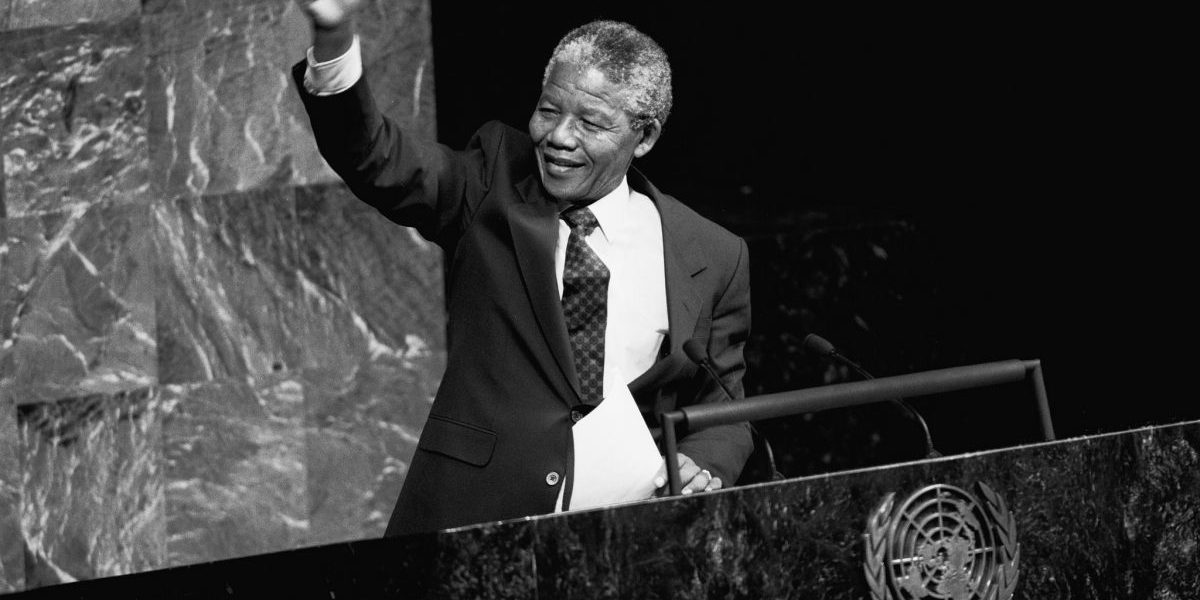

The 1960 UN Declaration on Decolonisation granted peoples the right to self-determination if they did not have their own state or were under colonial domination, alien occupation or racist rule. This right did not automatically legitimise violent means (or even secession), but subsequent UN General Assembly resolutions and declarations did condone the waging of armed struggles by recognised liberation movements. The UN also granted observer status to a number of liberation movements in the General Assembly.

Defining terrorism is more problematic. Despite several international conventions against terrorism, there is, as yet, no agreement on what the term refers to. Scholars have found no less than 109 definitions used from 1936 to 1981. The one used by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, for example, contains three elements: illegal use of force; intention to intimidate or coerce; and underlying political or social motives.

Apply this definition to the ANC or Zanu-PF and the difficulty of distinguishing between terrorist groups and liberation movements becomes apparent.

The Security Council has never legitimised the use of force by any liberation movement, but it does have the authority to decide when force is legal under international law. Even then, however, not all acts committed in the course of an internationally recognised armed struggle would automatically be acceptable. Freedom fighters waging just wars still commit atrocities. Does that make them terrorists?

Legally, no. But practically, the answer often depends on who holds the power to affix the label.