Uganda’s 2009 APRM Country Review Report recommended structural changes to important electoral institutions, expressed concern at the removal of term limits in 2005 and criticised what it saw as growing authoritarianism and an increasingly overbearing executive. The APRM advocated for greater independence for the electoral commission – which currently comprises of 7 electoral commissioners appointed by the president – but these recommendations were never adopted.

Though the APRM’s advocacy was unsuccessful, how else might the instrument have influenced the electoral process?

Click here to visit SAIIA’s APRM Toolkit, a comprehensive repository of APRM knowledge for continental practitioners, civil society members, academics, students, journalists and donors.

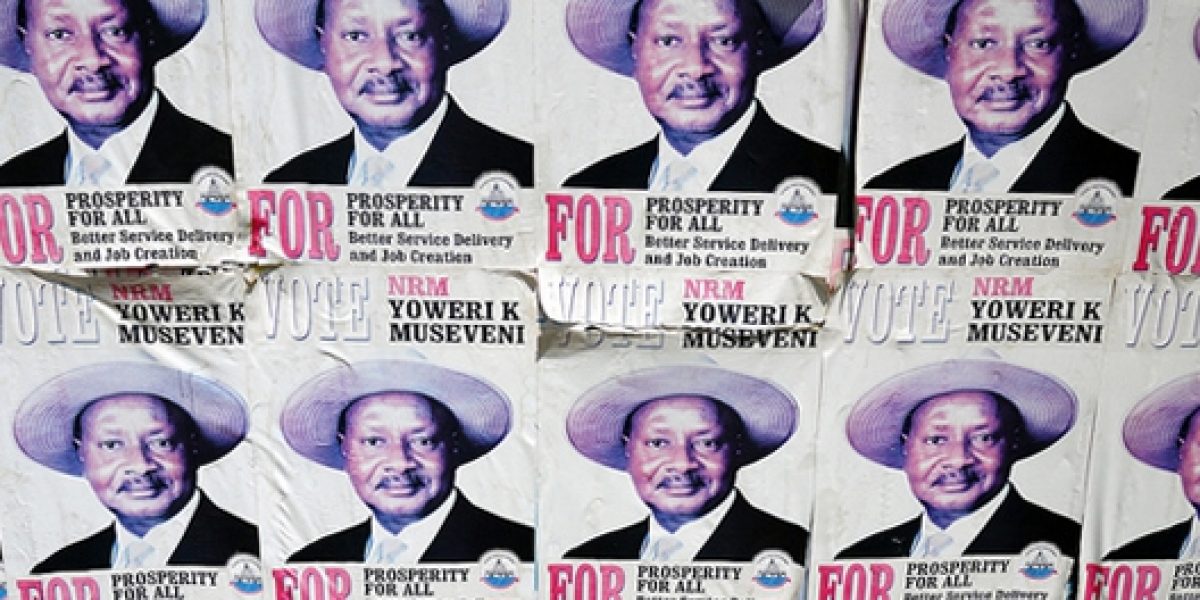

The battle lines for the 2016 election are drawn – septuagenarian President Yoweri Museveni, who took power in a coup in 1986, will be facing off against two of his erstwhile closest allies. The first, Dr Warren Kizza Besigye, is a former military colonel and was Museveni’s personal physician during the 1980s bush war. Besigye is the current presidential candidate for the country’s largest opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). The second is the ruling National Resistance Movement’s (NRM) former Secretary General and the country’s former Prime Minister, John Patrick Amama Mbabazi, who was dishonourably removed from both posts late in 2014 after a public fallout with the president.

A battle-hardened opposition leader, Besigye has faced down teargas, police beatings, treason charges and multiple arrests and 2016 will be his fourth stab at the presidency. Mbabazi is a regime insider who is responsible for some of the most nefarious legislation that has been directed against opposition parties, but he is standing on a reformist platform which argues that the ideals and goals of the ‘original’ NRM have been subverted by a party-state executive bent on power-retention. The real reason for the fallout is widely believed to be a promise made by Museveni in 2006 that by 2016, he would hand over power to Mbabazi.

The political opposition in Uganda is fairly weak, a product of 20 years of a de facto one-party system and a raft of repressive legislation enforced by a heavy-handed state. Every election since 1996 has seen some type of pre-electoral alliance or coalition formed by opposition forces, engendered by political pragmatism, individual self-interest and a weak and fragmented party system.

But this year’s coalition is qualitatively different. The result of an iterative process of learning lessons from past mistakes, the 2016 opposition coalition is the most reasoned and coherent to date. Named The Democratic Alliance (TDA), it represents seven political parties (including the FDC) and two pressure groups (one of which is fronting Amama Mbabazi); it has a number of formal structures such as a secretariat and a decision-making ‘summit’ at which all parties’ leadership is equally represented, as well as policy and candidate selection committees designed to produce common policy platforms and select joint candidates. However, one of the most interesting things about this coalition is the unprecedented involvement of sections of Ugandan civil society.

Historically, civil society in Uganda has been considered predominantly weak and fragmented. Lacking a vibrant union sector, civic engagement has traditionally been localised and largely driven by religious bodies. However, over the last decade, civil society has begun to come of age and the NGO sector has begun to flourish. The service-delivery orientation of the 1990s has largely been replaced with a governance and human rights-focused agenda which has brought NGOs into increasing confrontation with the Ugandan government.

In 2009, Bishop Zac Niringiye – the former Assistant Bishop of Kampala Diocese – was appointed by President Museveni to be Chairperson of the Ugandan APRM National Governing Council (NGC), the multi-stakeholder body overseeing Uganda’s peer review process. Bishop Zac, in spite of having been appointed by the president, became increasingly critical of the NRM government during his time on the NGC. In an interesting twist of events, he now heads the national secretariat of the opposition alliance, the TDA. He is one of a number of civil society leaders who have become involved in a process of trying to achieve unity and policy coherence within the disparate opposition. Sections of civil society in Uganda have begun to see involvement in the party political process as one of the key means of engaging with the state, following what they claim are attempts to frustrate their engagement on governance issues.

A number of civil society actors in Uganda have highlighted the importance of the APRM process in shifting the concerns of civil society in the country and providing information that has been used as a benchmark against which to measure progress on governance issues. Bishop Zac is just one of these people; he specifically highlights his involvement in the APRM as having been a key turning point in his advocacy on governance and human rights issues. The process opened up the conversation with the state and allowed for a more open appraisal of Ugandan governance successes and failures. Though Niringiye charges that the process staggered due to a lack of political will to implement key changes (while some members of the APRM process credit the lack of progress to Bishop Zac’s style of engagement and the absence of a more diplomatic approach towards key state institutions), he suggests that it was an important driver of collaboration within civil society and one which has had an impact far beyond its initial scope.

The goal to try to unite the Ugandan opposition and present a real set of policy choices to voters is a noble one. When measuring the success of initiatives such as the APRM, many seek to tally up successes – points at which interventions can be measured in terms of their influence the policy process. That which frequently goes unnoticed is the way in which the APRM forges links between different NGOs, connects the dots in governance and increases the information available for civil society advocacy on citizens’ issues.

The APRM is, at its heart, more a political than a technocratic process and it is thus somewhat unsurprising when governments attempt to frustrate progress. This makes it particularly important to focus on how the process plays out in more subtle ways, such as encouraging a more confident and vocal civil society sector. The 2016 election is likely to be fraught, but hopefully the involvement of civic actors might lead to a more enlightened citizenry and more organised and mature opposition parties, rather than being – as we see all too often on the continent – an election without real choices.

Nicole Beardsworth is a former SAIIA researcher. She is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Warwick in the UK, working on party and civil society coalitions in Uganda, Zimbabwe and Zambia. She just completed 11 months of fieldwork in Kampala, Harare and Lusaka.