Recommendations:

- To address food security gaps, it is necessary to focus on local and indigenous food systems. This will increase self-sufficiency, promote cultural food preferences and acknowledge the multidimensionality nature of agriculture.

- The G20 should roll out an action plan to realise the 2008 AFSI, which has the potential to bring parity to the food trade and address the concerns raised by the food sovereignty movement. Such an action plan could increase farmers’ incomes; lower the cost of food; and raise real wages.

- Synchronising domestic food policies within the G20 community will do much to encourage sustainable food systems.

- The World Food Systems Summit should draw up a framework to encourage the participation of the private sector in the post-COVID-19 food security strategy. It should also focus on transforming food systems to make them inclusive, with an efficient and effective supply chain.

Executive summary

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the trade war between China and the US, competing paradigms on the relationship between food trade and security have become more complex than ever ahead of the UN World Food Systems Summit in 2021. The opportunities presented by food trade liberalisation are under threat as more and more developed economies turn to protectionism to insulate themselves against the pandemic. This is jeopardising the food security of countries that depend on food imports. With food reliance under siege, especially in the developing world, the World Food Systems Summit should focus on strengthening local and indigenous food systems that create selfsufficiency. The G20’s food security initiatives have the potential to push for a food security framework that synchronises domestic policy reforms in its community and strengthens strategic policy coordination among the major global players.

Introduction

Eradicating hunger is an urgent UN Sustainable Development Goal.1UN, Sustainable Development Goals Report (New York: UN Publications, 2009), https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/millennium-development-goals-report-2009.html.Achieving this goal hinges on increasing food security. An estimated 821 million people in the world are hungry (while 2 billion are obese).2Food and Agriculture Organization, Report of the Thirty-fifth Session of the FAO Regional Conference for Asia and the Pacific (Rome: FAO, 2020), http://www.fao.org/about/meetings/aprc35/en/.Furthermore, food security indicators point to an increasingly desperate situation post-COVID-19 in most developing countries.3UN, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition” (Policy Brief, UN Sustainable Development Group, New York, 2020), https://reliefweb.int/report/world/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-food-security-and-nutrition-june-2020.Trade has been at the centre of securing food at household, community and national levels. Two opposing views have emerged over time about the relationship between food security and trade – in one, trade is an opportunity for food security, while in the other it is a threat to food security.4Jennifer Clapp, “Food Security and International Trade: Unpacking Disputed Narratives – The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2015–16” (Background Paper, FAO, Rome, 2015), http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5160e.pdf.

The search for a balance between the two views continues to dominate the food security debate and practices. As the world meets to address food security issues at the UN World Food Systems Summit in 2021, this policy briefing looks at how opportunities can be harnessed and threats mitigated in the context of emerging trade patterns driven by strong ant-liberalism calls, COVID-19, climate change and trade wars. It also examines how the G20 can help to secure an equitable global food system.

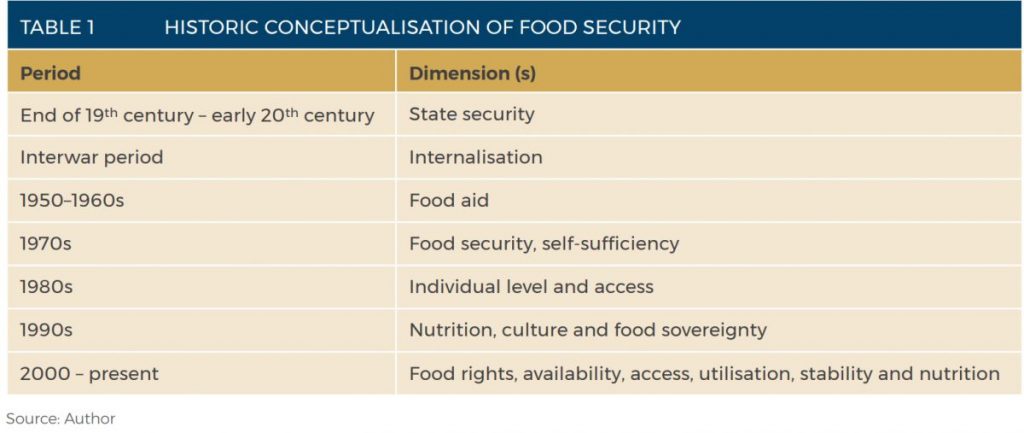

The concept of food security has evolved over the past two centuries. The traditional view, held at the beginning of the 20th century, saw food as part of national security. In anticipation of being attacked by other states, a nation had to have an adequate stock of food supplies from its domestic market. As the threat of invasion diminished, nations turned to international markets for food. This internationalised food security.5Simon George-André, “Food Security: Definition, Four Dimensions, History” (Basic Readings, FAO, Rome, 2012), http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ERP/uni/F4D.pdfAfter the First World War the League of Nations ushered in multilateralism to address hunger. In 1945 the UN, through the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), created the modern platform of internalisation in food security.

The focus in the 1950s and 1960s was on food aid. Influenced by the Cold War dynamics, hunger played a role in the geopolitics of the time. The developed countries that produced food surpluses donated these to those developing countries that faced famine.

In the 1970s the term ‘food security’ was used. At the 1974 UN World Food Summit, food security was defined as the ‘[a]vailability at all times of adequate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices’.6FAO, Trade Reforms and Food Security: Conceptualizing the Linkages (Rome: FAO, 2003), http://www.fao.org/3/a-y4671e.pdfThis conceptualisation took place against a backdrop of global food crises that gave rise to distorted grain prices. It was also at this point that the shift from food aid to self-sufficiency was promoted by the US through its Green Revolution programme.7Prabhu Pingali, “Green Revolution: Impacts, Limits, and the Path Ahead”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States 109, no. 31 (2012): 12302–12308, https://www.pnas.org/content/109/31/12302.

During the 1980s the concept of food security was expanded to include individuals and access. In 1983 FAO defined food security as: ‘Ensuring that all people at all times have both physical and economic access to the basic food that they need.’ 8FAO, Director-General’s Report on World Food Security: A Reappraisal of the Concepts and Approaches [1982], Conference Report (Rome: International System for Agricultural Science and Technology, 1984), https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF8333115.The focus was at an individual level. To be food secure, an individual had to have access to food, leading to an active and healthy life.

In the 1990s three concepts were added to the dimension of food security, namely nutrition, culture and sovereignty. Food had to be nutritious and satisfy people’s dietary requirements.9FAO, Report of the World Food Summit, 13–17 November 1966 (Rome: FAO, 1996), http://www.fao.org/3/w3548e/w3548e00.htm.Calls for food sovereignty grew louder during this decade. The rights of people and nations to determine their own food systems received more attention. The Nyeleni Declaration consolidated this notion,10Nyeleni 2007, “Declaration of Nyeleni”, February 27, 2007, https://nyeleni.org/IMG/pdf/DeclNyeleni-en.pdf.stating that food security was a basic human right. The food sovereignty dimension thus challenged the food trade status quo.

At the turn of the millennium, food rights gained a bigger foothold in the conceptualisation of food security, and FAO adopted the 2004 Right to Food Guidelines.11FAO, Voluntary Guidelines: To Support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security (Rome: FAO, 2005), http://www.fao.org/3/a-y7937e.pdf.Four pillars now supported food security: availability, access, utilisation and stability.12FAO, Voluntary Guidelines.On the nutrition front, protracted undernourishment, micronutrient paucities and over-nourishment consolidated the food security concept.13FAO, Voluntary Guidelines.

Food trade issues have been contentious. This has been ascribed to several causes: food is vital to people’s survival; and the agricultural sector employs more than 30% of the world’s workforce. It is a foreign currency earner in some states, and food imports are crucial in others.14Clapp, “Food Security and International Trade”.

Two models – food exceptionalism and trade liberalisation – have thus dominated the food trade for the past two centuries. The former advocates the protection of domestic markets, the latter, free trade.15Derick Headey, “Rethinking the Global Food Crisis: The Role of Trade Shocks”, Food Policy 36, no. 2 (2011): 136–146, https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/jfpoli/v36y2011i2p136-146.html.

Food trade dynamics: The impasse

Trade in food has always been considered in international trade forums such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) of 1947–1993 and, more recently, the World Trade Organization (WTO). The question of whether the food trade should be liberalised or protected has long defined the search for food security. This question has preoccupied governments, academics and civil society and, after the food price crisis of 2007, has been at the centre of the debate on how trade measures can contribute to food security. To date, there is no agreement on this issue.

Drawing on FAO’s concept of food self-reliance that promotes trading as a way of securing food,16Clapp, “Food Security and International Trade”.liberalising food trade is supported by the WTO, World Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and developed countries. At the same time, the developing world advocates protectionism,17Headey, “Rethinking the Global Food Crisis”.based on the ideal of food sovereignty. Interestingly, the emerging trade war between the US and China has seen the use of protectionism. On 9 May 2020 the US increased tariffs on $200 billion worth of goods, and in retaliation China imposed tariffs on $60 billion worth of goods a few days later.18Dorcas Wong and Alexander Chipman Koty, “The US–China Trade War: A Timeline”, China Briefing, May 15, 2020, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/the-us-china-trade-war-a-timeline.Food trade policies are thus subject to national and geo-political priorities.

Supporters of food trade liberalisation believe that free trade promotes food security. Three arguments are prominent in their defence of free trade: comparative advantage; trade as a conveyor belt of food supply and demand; and the negative impact of trade barriers on food security.19Clapp, “Food Security and International Trade”.‘Comparative advantage’ holds that nations will benefit from trading in what they have an advantage in producing. The trade in idiosyncrasies promotes specialisation, increases world welfare and leads to efficiency gains. This improves both food availability and food access.20World Trade Organization, “Trade Is Vital for Food Security, Lamy Tells Agricultural Economists”, World Trade Organization News, August 30, 2011, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/sppl_e/sppl203_e.htm.

By moving food from surplus to deficit areas, trade liberalisation balances supply and demand. While some regions cannot produce enough food, others produce a surplus, and their trade interaction mitigates the threat of food insecurity.21Will Martin, “Agricultural Trade and Food Security” (Working Paper 664, Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo, February 2017), https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/228906/adbi-wp664.pdf.Given fluctuations in weather patterns, agricultural production on a global scale is more steady over time than agricultural production at the national or regional level, hence trade redistributes food supplies to meet demand. Furthermore, the movement of food is a major factor in stabilising food prices.22Martin, “Agricultural Trade and Food Security”.

In the pro-food liberalisation argument, comparative advantage theory is based on the assumptions that all trading partners benefit; and that there is a stasis of capital and labour among traders, perfect competition, and perfect movement of capital and labour in a country.23Jennifer Clapp, Trade Liberalization and Food Security: Examining the Linkages (Geneva: Quaker United Nations, 2014), https://quno.org/sites/default/files/resources/QUNO_Food%20Security_Clapp.pdf.Without the fulfilment of these assumptions, comparative advantage struggles to sustain trade liberalisation as a promoter of food security. It comes as no surprise that trade imbalances among partners have contributed to the growing anti-liberalisation stance in food trade circles.

Sophisticated global value chains dominated by a few powerful transnational corporations compromise the theory of comparative advantage. For example, about 70% of the world’s grain market is controlled by four firms,24EcoNexus, “Agropoly: A Handful of Corporations Control World Food Production”, September 2013, https://www.econexus.info/sites/econexus/files/Agropoly_Econexus_BerneDeclaration.pdf.and a handful of transnational corporations control a large share of the tropical commodities markets in developing countries.25UN Conference on Trade and Development and FAO, Commodities and Development Report 2017: Commodity Markets, Economic Growth and Development (New York: FAO, 2017), https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/suc2017d1_en.pdfThis set-up creates structural and technical deficiencies in trade liberalisation as an opportunity for food security. Capital mobility, inefficiencies and food price volatility eclipse efficiency gains and compromise comparative advantage. Furthermore, the resultant profits go to these corporations, leaving host farmers and countries at a disadvantage.

The economic cost of protectionism through tariffs and import duties increases food prices and threatens food security. Agricultural protection measures such as import and export quotas breed unproductive policies that weaken food chains and raise prices, as reported by the World Bank.26World Bank, Global Monitoring Report 2012: Food Prices, Nutrition, and the Millennium Development Goals (Washington DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank, 2012), https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gmr/2012/eng/gmr.pdf.

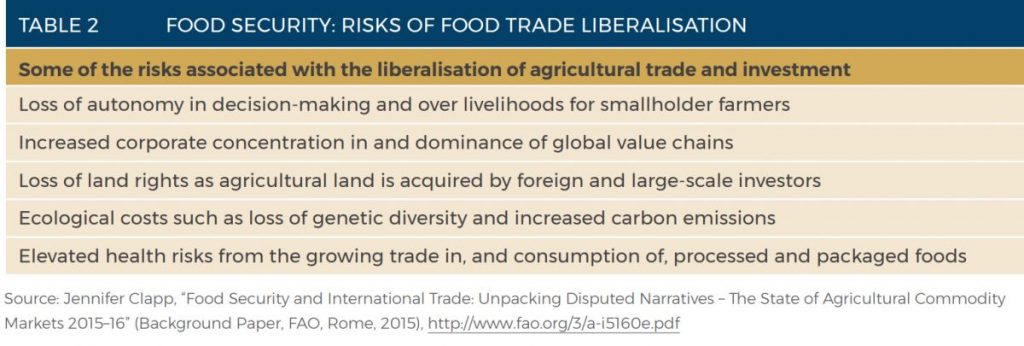

The post-2007 food price crisis saw growing support for anti-food-trade liberalisation. Feeling the impact of food price volatility and increases, food-importing countries pushed for a new order in organising food and agriculture systems to reduce reliance on global markets and increase self-sufficiency.27Headey, “Rethinking the Global Food Crisis”.The main lesson learnt was that ‘trade is a threat to food security’, hence the need to drastically reduce reliance on international trade for food security and instead focus on local smallholder farmers and biodiversity to secure food locally. This viewpoint does acknowledge the need for food trade, but emphasises local production. Food security should thus prioritise local food systems. If anything, food should be treated as a unique case in trade policy. The mainstays of this approach are thus food sovereignty, the multifunctionality of agriculture and an emphasis on the risks associated with agricultural trade liberalisation.28Clapp, “Food Security and International Trade”.

The food sovereignty paradigm is guided by the belief that food is a national and community security issue. All countries premise their political security strategy on self-sufficiency in terms of food.29Clapp, “Food Security and International Trade”.The thrust of this view is that it is every nation’s right to pursue food systems that create food security for its population, by taking charge of market relations, and ecological and cultural issues.30Raj Patel, “Food Sovereignty”, The Journal of Peasant Studies 36, no. 3 (2009): 663–706, DOI: 10.1080/03066150903143079.It is a nation’s right to determine what food to produce, how much to stockpile as a buffer against global market shocks, and what to export.

It is against this backdrop that many countries are pushing for the exceptional treatment of food in the international trade regime. The food sovereignty movement gained momentum in the 1990s and was given prominence by the Nyeleni Declaration.31Nyeleni 2007, “Declaration of Nyeleni”.The major point of contention is that developed countries are generally food secure and view food trade as more of a commercial concern than a security issue. In contrast, the developing world struggles with food security, and food trade is a security issue rather than a commercial one. So the divide becomes apparent: trade liberalisation is advocated by the developed world and food sovereignty and protectionism by developing countries.

Beyond being a tradable good, agriculture has a multifaceted role in various societies. In the developing world it is the mainstay of rural livelihoods, while in the EU it preserves rural landscapes in culture and identity as well as being a provider of ecological services.32Bingjie Song, Guy M Robinson and Douglas K Bardsley, “Measuring Multifunctional Agricultural Landscapes”, Land 9 (2020): 260–273, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/9/8/260.This multifunctionality of agriculture has strengthened calls to give agricultural trade a special place in international trade policy. It has also provided food sovereignty advocates with a platform to press for a local focus in food issues so that all these functions of agriculture be given the attention they deserve.

This underlines the need to find a balance between the various threats and opportunities trade holds for food security.

How has the world responded so far to the food trade impasse, and how effective are these responses? Various global agreements, policies and declarations have tried to address the balance. Under the 1947 GATT food was exempted from trade rules.33WTO, “General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade” (WTO Agreement Series 2, WTO, Geneva, 2014), https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/agrmntseries2_gatt_e.pdf.Food exceptionalism was strongly supported by the US. Food aid from surplus production in the US, subsidies and other protection mechanisms distorted the food markets and threatened food security. Food aid undermined domestic food production in developing countries and subsidies made it difficult for exporting countries to compete in the food market.

As a result of neo-liberal economic policies and the challenges of the GATT regime, the move to liberalise the food trade gathered momentum in the 1980s. The Uruguay Round (1986–1994) through the WTO Agreement on Agriculture liberalised food trade.34WTO, “General Agreement on Tariffs”.With reduced tariffs and developing countries’ opening their markets to major players, the playing field in the agricultural trade remained uneven and threatened food security. Developing countries could not complete with cheap subsidised imports, making their domestic food systems too weak to secure food for their populations. The resultant inequalities are still in play, and have bolstered the movement against food trade liberalisation. The 2001 Doha Round under the WTO sought to address these inequalities. Food trade has also received attention outside the WTO, for example through the food sovereignty movement and the G20.

Food security and trade: The role of the G20

It is estimated that about half of the world’s chronically hungry people live in G20 countries, 65% of the world’s agricultural land is in G20 countries, and the G20 is responsible for about 77% of global cereal production and 80% of the trade in agricultural products.35Robbin Davis, Lorraine Elliott and Paul Belesky, “G20 Development Working Group Food Security Review: T20 Submission” (Paper, Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney, 2016), https://devpolicy.org/publications/submissions/G20-Development-WorkingGroup-Food-Security-Review.pdf.As a major player in the food trade ecosystem, how can the G20 help to address the threat trade poses to food security and enhance the opportunities?

As a group, the G20’s concerns about food security have become more noticeable since the 2007 world food price crisis. Beyond endorsing the multilateralisation of food security, and encouraging smallholder productivity and resilience to food price shocks through the 2008 L’Aquila Food Security Initiative (AFSI) and the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program,36G20, “Action Plan on Food Security and Sustainable Food Systems”, 2015, https://www.resakss.org/sites/default/files/G20%202015%20Action%20Plan%20on%20Food%20Security%20and%20Sustainable%20Food%20System.pdf.the G20’s involvement in food security was peripheral. The focus on smallholder productivity appealed to both sides of the food trade divide. To the food trade liberalists, it addressed the trade inequalities caused by major competitors’ subsidies. To the antifood trade liberalists, it spoke to strengthening local food systems. Food security issues also appeared on the agenda of the Development Working Group (DWG) at the Seoul Development Consensus.37Davis, Elliot and Belesky, “G20 Development Working Group”.Apart from its recognition as one of the nine development activities to be undertaken by DWG, there was no active involvement within the G20 on the matter.

In 2011, under the French presidency of the G20, the Action Plan on Food Price Volatility and Agriculture38Davis, Elliot and Belesky, “G20 Development Working Group”.developed by the G20 agriculture ministers heralded the organisation’s active role in food security matters. The Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS)39Agricultural Market Information Systems, Inception Meeting, FAO, Rome, September 15–16, 2011,was created to provide much-needed links between demand and supply in the global food chain. A more in-depth and direct effort is the Food Security Review (FSR),40Davis, Elliot and Belesky, “G20 Development Working Group”, http://www.amis-outlook.org.mandated by the G20’s Saint Petersburg Development Outlook in 2012.41G20, “Saint Petersburg Development Outlook”, 2012, http://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/development/St-Petersburg-DevelopmentOutlook.pdf.By linking the growth and employment agenda, and increasing agri-infrastructure development and access to financial services, the FSR initiative addresses the challenges developing countries face in their local food systems by focusing on domestic agriculture growth. This is meant to enhance community and state resilience in the face of external shocks, and resonates with the food sovereignty concept of developing countries. By addressing the pressures of food insecurity brought about by trade activities, the FSR initiative also acknowledges the multifunctional nature of agriculture by focusing on job creation and sustainable growth.

The AMIS, which has been adopted by FAO, has the potential to influence food security on a global scale by curbing market distortions.

The recent Agriculture G20 Ministers’ meeting has made various commitments on food security, namely to:

- cooperate with international organisations such as FAO in realigning food security strategies as demanded by the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic;

- attend to reducing barriers to food trade;

- consolidate food security information systems; and

- promote research on and feasible investments in food systems.

If these commitments are translated into action plans with a strong focus on the private sector and local food systems, the G20 is likely to effect a balance between trade and security post-COVID-19. The private sector can contribute by funding agricultural innovations targeted at increasing agricultural efficiency. The G20 Framework for Analysing Policies to Improve Agricultural Productivity Growth, Sustainably shows that the private sector’s investment in such innovations has thus far been minimal.42Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development, G20 Framework for Analysing Policies to Improve Agricultural Productivity Growth, Sustainably: Stocktaking 2012–18 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019), https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/agricultural-productivity-and-innovation/documents/g20-framework-ag-productivity-sustainability-stocktaking.pdf.

The use of artificial resources, such as fertilisers and genetically modified organisms, and the emission of greenhouse gases change water, carbon and nitrogen cycles and impact the fertility, health and biodiversity of landscapes. This is a hazard to ‘a sustainable food future’ as prioritised by the 2018 Argentinian G20 presidency.43G20, Overview of Argentina’s G20 Presidency 2018: Building Consensus for Fair and Sustainable Development (Toronto: G20 Information Centre, 2019), http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/.To mitigate this risk to food security, the G20 needs to support the Climate-Friendly Sustainable Agriculture (CFSA) initiative. This initiative lacks technical, financial and regulative support – something that the G20 could address in collaboration with FAO and other international food and agricultural agents.

The G20’s actions in directing trade as an opportunity for food security should be centred on synchronised domestic policy reforms within its community. Currently, G20 members’ domestic agricultural policies differ from each other to such an extent that a common integrated effort to influence international food trade is compromised. Agricultural subsidies that promote distortions in international trade still exist in developed members of the G20. Furthermore, the lack of harmony among G20 domestic policies on climate change, biofuels and food aid is conspicuous.

Towards the UN World Food Systems Summit

The UN World Food Systems Summit will take place against the backdrop of an impasse in food trade exacerbated by the trade war between China and the US, the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, famine and worsening food insecurity in developing countries. How can the summit balance the food trade challenge in a manner that fully addresses the food security pillars of availability, access, utilisation and stability?

The food liberalisation regime by and large has the potential to make food available, and at an affordable price. Specialisation and efficiency gains have resulted in increased food production on a global scale. Food availability for direct human consumption grew by 19% year on year between 1960 and 1994–96, to 2 720 kcal/day. This trend continued until 2015, after which annual growth slowed to 12% because of climate change and other factors, eg, natural disasters and conflicts.44Song, Robinson and Bardsley, “Measuring Multifunctional Agricultural Landscapes”.Furthermore, trade promotes food diversity, which leads to more balanced nutritional value. Yet COVID-19 food security-induced survival tactics have seen a number of traditional advocates of free trade in the developed world turn to protectionism.45Alvaro Espitia, Nadia Rocha and Michele Ruta, “COVID-19 and Food Protectionism: The Impact of the Pandemic and Export Restrictions on World Food Markets” (Working Paper 9253, World Bank, Washington DC, 2020), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33800.This is a potential disaster for countries that depend on food imports. East Africa has also had to deal with the devastation wrought by desert locusts.

Even though food availability has increased over the last decade, there are some notable inequalities in food availability in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Asia. Domestic production falls far below safe availability levels. After the Uruguay Round, food availability increased by 7% year on year from 1995–2005.46Steve McCorriston et al., What is the Evidence of the Impact of Agricultural Trade Liberalisation on Food Security in Developing Countries? A Systematic Review (London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, 2013), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237973599_What_is_the_evidence_of_the_impact_of_agricultural_trade_liberalisation_on_food_security_in_developing_countries.This was in contrast with the previous growth of 19% year on year recorded from 1964–1995. Liberalising the food trade makes food available, but purchasing power ensures food security. Purchasing power is thus the missing link in trade as an opportunity discourse.

Smallholder farmers and rural populations are sidelined by trade liberalisation. As the world meets to discuss food systems, more attention should be paid to food self-sufficiency in order to improve food availability through an all-inclusive trade reform agenda that accommodates smallholder farmers and rural populations in developing countries.

The trade in food increases supply, incomes and growth on a global scale. These incentives also contribute to improved access to food. Trade liberalisation has helped to lower domestic food prices, and so increases food access. It only becomes problematic when trade goes beyond lowering food prices to completely destroying local food systems. This necessitates food trade policy reforms that support local food systems, addressing the multidimensionality of agriculture often ignored by trade liberalisation.

Trade promotes food stability by mitigating domestic deficits caused by seasonal variability, climate change and conflict.47Song, Robinson and Bardsley, “Measuring Multifunctional Agricultural Landscapes”.Trade can also counterbalance global price fluctuations by stabilising supply. On the other hand, dependence on food imports can increase the risk of supply and access interruptions owing to global production instability and price volatility. Limited dependence on food imports is necessary to ensure food stability in developing countries.

Trade in food has to an extent maintained the pillars of food security, yet there are still gaps in food security that can be attributed to trade and that are more apparent in the developing world. The World Food Systems Summit needs to address these gaps. Furthermore, the environmental costs of the food trade, which include natural resource exhaustion and biodiversity loss, cannot be ignored in the developing world’s state of worsening food insecurity. Cheaper imports are also threatening to erode cultural food preferences.48Jennifer Clapp and Peter Dauvergne, Paths to a Green World: The Political Economy of the Global Environment (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2011), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhcr3

Conclusion

As the world meets at the World Food Systems Summit in 2021, the longstanding challenge of finding a balance between trade and food security needs urgent attention. Climate change, the trade war between China and the US and the COVID-19 pandemic have all made the situation even more acute. While food trade liberalisation promotes food reliance, it fails to support the local and indigenous food systems that are essential to food security, hence the calls for food sovereignty. Through targeted domestic food system support, the G20 has the potential to lead the world in stopping the gaps in food security.

To address the food security gaps laid bare by food trade deficiencies, it is necessary to focus on local and indigenous food systems. This will increase self-sufficiency and promote cultural food preferences, and attend to the multidimensionality nature of agriculture ignored by the food trade.

The G20 should go beyond calls to support small-scale farmers and roll out an action plan to realise the 2008 AFSI that ushered in the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program. Twelve years later this initiative is not supported by action despite its potential to bring parity to the food trade and address the concerns raised by the food sovereignty movement. Such an action plan could have a triple impact: increasing the incomes of farmers; lowering the cost of food for poor consumers; and raising real wages.

Synchronising domestic food policies within the G20 community will go a long way in in coming up with sustainable food systems. The trade war between China and the US is a major threat to a common consolidated G20 position on food security.

The summit should also come up with a framework to encourage the participation of the private sector in the post-COVID-19 food security strategy. Governments’ agricultural subsidies are likely to be impacted by the pandemic.

In these circumstances, the summit should focus on transforming food systems to make them inclusive, with an efficient and effective supply chain. The world needs a trade structure that will increase food security and promote sustainability.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to Dr Mthokozisi Mlilo, Senior Lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Economics and Finance, for peer reviewing this policy briefing.

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Konrad Adenauer Fountdation for this publication.