Recommendations

- Increasing recognition of OECMs will help engage a diversity of actors in local-to-international conservation processes and improve linkages between equitable conservation and effective conservation outcome.

- Innovative finance and enhanced people-centred approaches are required to encourage the effective implementation of OECMs.

- A common position needs to be developed in the lead up to the CBD COP to ensure that African governments are aligned on the importance of community-centred conservation.

- Communities are complex structures with varying norms and cultural practices. It is therefore important that context-specific research is conducted before piloting.

Executive summary

Protected areas and other types of biodiversity-focused management tools play an integral role in safeguarding and restoring Africa’s biodiversity, which in turn enhances the resilience of ecosystems in building a defence against climate change. Various models of area-based management tools have been developed, increasing over time to include areas that are not recognised under the formal banner of protected areas, but that play an equally important role in contributing to achieving long-term biodiversity, climate change and sustainable development targets. For Africa, these ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ are particularly important, as much of the continent’s wildlife and biodiversity exists outside protected areas.

However, despite their growing significance, many of these OECMs do not yet contribute significantly to the livelihoods of nearby communities. This briefing highlights successful examples of community-driven initiatives in Africa and their lessons around the constraints and hurdles for achieving adoption, buy-in and scaling of these models.

As African negotiators approach the Conference of Parties to the Convention of Biological Diversity in China this year, they should collectively advocate for increased communitydriven biodiversity initiatives within both protected areas and through other area-based conservation measures.

Introduction

Protected areas are established to safeguard vulnerable biodiversity, while contributing to ecosystem services and the livelihoods of local communities bordering such areas. However, many protected areas struggle to adequately take into consideration the needs of nearby communities. The establishment of protected areas in Africa, many of which were first demarcated under colonial rule, resulted in communities being removed from their land and a significant loss of livelihood opportunities and income. Communities were no longer able to access rangeland or harvest key natural resources such as food, firewood, and medicinal herbs. Often, the only available work for these communities is in eco-enterprises, such as tourism activities, with only a few members of the community benefitting.

The global recognition that nature needs adequate space should go hand in hand with recognizing that community landowners adjacent to protected areas who are willing to accommodate dangerous elements of nature on their land should derive some benefit for doing so. As such, frameworks like OECMs were created to encourage an enabling environment for communities to continue to build a connected relationship with land that provides socio-economic benefits for local people, while also providing incentives for the protection of wildlife and the preservation of the natural resource base on which these communities rely. OECMs are sites outside protected areas that are governed and managed in ways that deliver long-term, in-situ biodiversity and socio-economic benefits. While protected areas must have a primary conservation objective, OECMs may be managed for many different objectives, though they must also deliver effective conservation benefits. The main difference between OECM and other community driven conservation models, is that OECMS are not initiatives. OECMs’ are a global standard agreed through the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) that can be applied to a range of sites – where they meet the necessary criteria, these sites can then be reported as part of a country’s commitments under the CBD.

The concept of OECMs first appeared in international law in Target 11 of the CBD’s Strategic Plan for Biodiversity. This plan called on Parties to conserve 17% of terrestrial areas and 10% of marine areas through well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (targets that are likely to be expanded under the post2020 global biodiversity framework). OECMs have gained considerable traction globally as a possible means to simultaneously address the increasing development and ecological crises of our time, while improving the linkages between equitable conservation and effective conservation outcomes. OECMs are areas that align with the OECM criteria and may be governed under a range of possible governance types, including government agencies, private interests, indigenous peoples, and local communities. These partnership arrangements vary in size, from an isolated area to a landscape level initiative, and create space for the integration of wildlife conservation and management objectives into land ownership arrangements.

Economic and livelihood incentives for communities and landowners, linked to the protection of wilderness, is a win-win for both people and the planet and should be at the forefront of negotiating positions leading up to the CBD Conference of Parties (COP) meeting in September 2021, which is expected to see the establishment of a post-2020 global biodiversity framework. As such, incentives need to be further encouraged for landowners to create more space for nature, help offset costs associated with the presence of wildlife on their land, and place conservancies on a path to sustainability. To achieve this there is an urgent need to unlock biodiversity-focused financing and nature-based economies for unprotected areas and OECMs.

Building a long-term, sustainable relationship with nature both in and outside of protected areas requires allocating the necessary resources, developing capacity and empowering local leaders, and establishing tenure structures that make the communities custodians of the land. The 2021 ‘Territories of Life’ report indicated that if we are to achieve the new biodiversity targets required by an ambitious post-2020 global biodiversity framework, a rights-based approach must be adopted, one that upholds equitable collaboration between indigenous people, local communities, governments, conservation practitioners and private actors.

This briefing will examine three case studies that illustrate how communities can enhance their socio-economic realities through nature protection by building partnerships with government, the private sector and conservation agencies. These examples can serve as guidance to scale-up community conservation efforts in all areas that have been identified as critical for the conservation of native species, biodiversity, and ecosystem services. They can also act as a catalyst to engage a diversity of actors in local-to-international conservation processes.

The case of Nambiti Private Game Reserve, South Africa

The Nambiti Private Game Reserve in the Tugela basin in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, provides a useful case study for the wildlife ranching sector, as it combines clear biodiversity conservation objectives and strong financial and economic imperatives, all within the context of a community-private sector partnership.

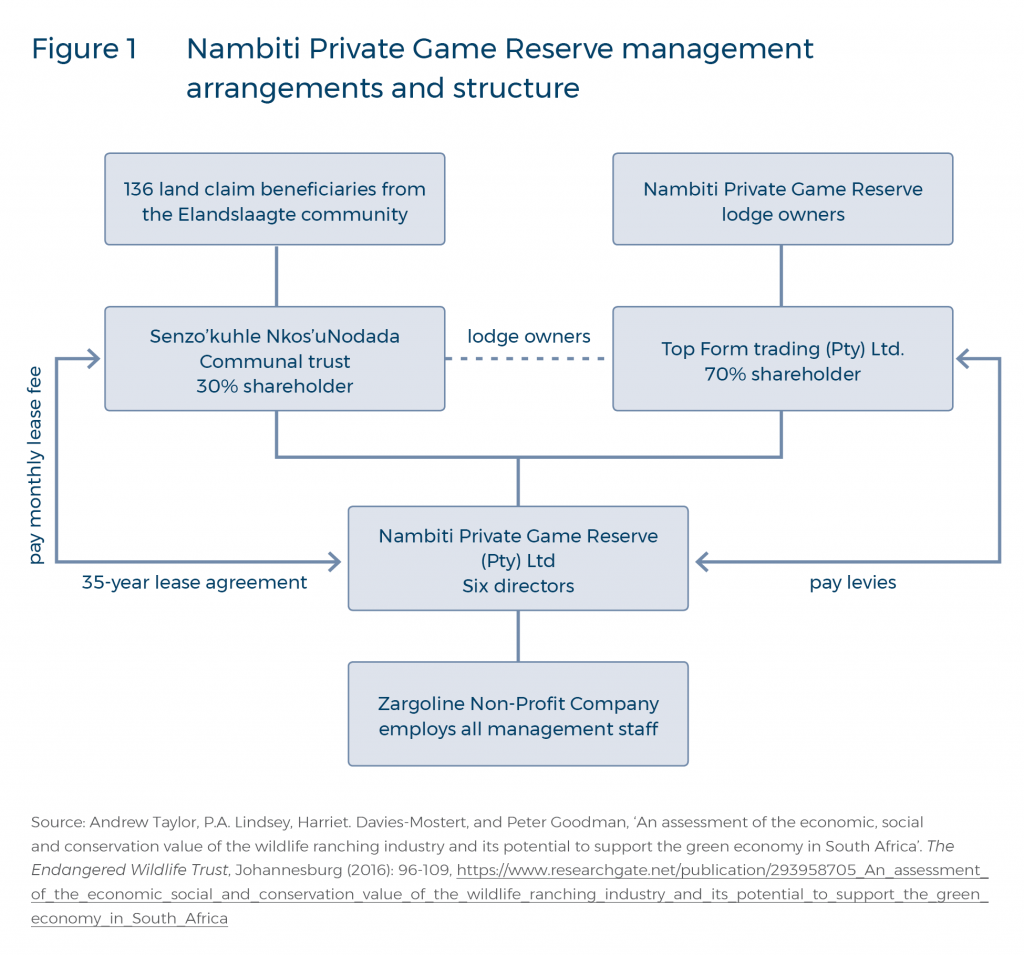

This private reserve was initially established by a group of businessmen through the purchase of a number of farms and the re-introduction of game. Subsequently, the reserve underwent a successful land claim, and a partnership was formed with the Elandslaagte Community, who then developed the Senzo’kuhle Nkos’uNodada Communal Trust to legally represent the 136 successful land claimants from the community. The land was transferred to the community in June 2009 and is not under any tribal authority. All decisions regarding the management of the land and its resources are taken by the trustees.

The Nambiti Reserve now has ten luxury game lodges catering to local and international tourists. It also has limited hunting, live capture, sale of game, and production of venison from a recently constructed abattoir and butchery. The Senzo’kuhle Nkos’uNodada Communal Trust benefits from the Nambiti Reserve through lease fees, ownership and operation of one of the lodges on the reserve, and the shares of profits from hunting, live off-takes and sale of venison. The lodges also employ community members and offers training to upskill staff. Other economic benefits to communities include the harvesting of invasive vegetation for firewood and thatch, which is sold at a low price to Trust members and surrounding communities. This harvesting improves the ecological footprint of the reserve as alien plants are eradicated.

The reserve is also home to significant biodiversity and ecological infrastructure, qualifying it to be proclaimed as a nature reserve in terms of the KZN Biodiversity Stewardship Programme. The reserve falls on an ecotone (a transition area between two vegetation zones) that includes Tugela Thornveld in the south and east and Northern KwaZulu-Natal Moist Grasslands in the north and west. The protection of the reserve makes a significant provincial and national contribution towards the achievement of protected area targets.

The case of Dixie Community Rangeland, South Africa

The Dixie Community Rangeland showcases how a traditional authority was approached to engage with OECMs through working off an existing mutually beneficial relationship between Conservation South Africa and the traditional authorities of the Dixie community in the communal lands of the Greater Kruger Transfrontier Conservation Area. The existing relationship with the Dixie community was developed through the establishment of a Biodiversity Stewardship Programme, an approach which encourages agreements with private and communal landowners to protect and manage land in biodiversity priority areas in South Africa. This existing relationship helped to leverage and integrate a collaborative rangeland management plan within the OECM framework. Between 2008 and 2016, 68% of all protected area expansion was achieved through biodiversity stewardship, which costs the state between 70 and 400 times less per hectare than land acquisition.

The conservation agreements private partnership platform report states that over the past three years 7 600 hectares of high biodiversity rangelands have been secured through new agreements with livestock farming associations and with two additional villages in the area who have since been seen as potential OECM sites, totalling around 348 people. The key conservation action, switching from unplanned, continuous grazing to ecologically informed rotational grazing, was implemented across the target grazing areas, and further work was done to enhance the internal governance of the grazing associations, including democratic nomination and implementation of new leadership.

A private partnership was also developed with Meat Naturally, an initiative that supports rural farmer development, regenerative agricultural practices, and socio-economic development. This initiative developed a suite of benefits for compliance with rangeland conservation measures, including meat markets, livestock fodder, and livestock technical support. The final project performance report noted that Conservation South Africa had successfully conducted farmer organisations under the conservation agreements and sold livestock at market price. This process allowed for valuable learning exchanges between the villages, Conservation South Africa rangers and the Kruger to Canyons eco-monitoring team.

A challenge they encountered was that Meat Naturally was unable to be a consistent livestock buyer in the area due to stringent foot and mouth disease regulations.

Improved rangeland management has significantly increased vegetation cover and assisted with community-led monitoring and removal of alien invasive species (in collaboration with Kruger to Canyons biosphere and South African Parks). Strengthened local capacity to implement improved rangeland management has also resulted in positive socioeconomic benefits for the communities such as improved access to information, training, and livelihood opportunities for stewards through private sector partners (trail slaughter, market-relevant prices, animal health training, and livestock fodder). Training has also significantly enhanced the agency of community stewards, within farmer organisations, to engage productively with each other and government agencies around rangeland governance.

The case of community-private sector partnerships in Kenya

Much of Kenya’s wildlife and biodiversity exist outside protected areas, making OECMs crucial for its long-term conservation. Currently, about 65% of Kenya’s wildlife exists in wildlife conservancies, while another substantial proportion occurs in other areas that are either privately, communally or government owned.

A conservation approach that engaged communities and private landowners living in priority wildlife areas in the mid-1990s resulted in the creation of wildlife conservancies that have more than doubled the area under some form of protection in just 20 years. The conservancy movement was driven by the need to address the human-wildlife conflict in areas adjacent to protected areas. In 1995, the Kenya Wildlife Services (KWS) embarked on a campaign called ‘Parks Beyond Parks’ with the aim of creating space for conservation initiatives outside of parks and to encourage the integration of wildlife conservation and management objectives into privately owned land and community spaces. These efforts have demonstrated the potential of utilizing community-corporate partnerships, under the sustainable agriculture and wildlife economies, to drive area-based conservation outcomes though the OECMs model.

Key to achieving the goals of Parks Beyond Parks was the promotion of communitybased conservation and natural resource management as a means to expand space for wildlife and biodiversity in the rural landscape through the Minimum Viable Conservation Area (MVCA) approach. This approach identifies critically important areas for long-term conservation of biodiversity based on three criteria, namely, biological, economic, and social. The biological criterion identifies the areas needed to sustain the protected area and the associated wildlife dispersal zones, as well as non-protected areas critical to sustaining Kenya’s biodiversity. The economic criterion identifies additional areas such as zones that link tourism circuits or support critical ecological services (e.g., watersheds). The social criterion highlights culturally valued habitats, which further instills culturally appropriate methods and community engagement with the project. For each protected area, the MVCA encompasses the adjacent areas that were considered necessary to maintain the integrity of the constituent biological communities, habitats and ecosystems, support important ecological processes, meet the habitat requirements of wide-ranging species, and support key economic and social functions.

Stakeholders and their interests and conflicts were identified in each MVCA, and terms and conditions for meaningful engagement of landowners and community groups in biodiversity conservation agreed upon. Once established, the MVCA formed the basis for ecosystem planning, human–wildlife conflict management, community engagement and integrating national parks into the wider landscape.

Challenges for enhancing OECMs

Communities need to become custodians of their land and the associated biodiversity, with clear collective rights that are recognised by a broad base of stakeholders. In South Africa, a community is able to register as a common property association and become a legal custodian authority, and therefore have a role in the various enterprises on the land. However, in practice, power and politics within communities can be disabling and lead to unjust outcomes. Mechanisms for transparency and accountability are therefore essential to avoid elite capture of natural resources by a few, as well as to ensure the fair distribution of benefits community-wide, particularly to women and children.

Communities are diverse and complex entities with varying norms and cultural practices. There is no “one size fits all” solution when it comes to the adoption of OECMs in specific communities. Communities have unique approaches to communication, authority and engaging with the landscape. They can also dramatically differ in size and capacity, and it is important to understand the specific challenges that communities face.

Jonas et al. explain that progress in defining and reporting on biological, economic and social outcomes of OECMs can be slow, mainly because of uncertainty of what to report on and how to measure effectiveness.1Harry D. Jonas, Valentina Barbuto, Holly C. Jonas, Ashish Kothari and Fred Nelson, ‘New Steps of Change: Looking Beyond Protected Areas to Consider Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures’, The international Journal of Protected Areas and Conservation, issue 24, June 2018, 10.Furthermore, with any new people-centred conservation frameworks there will likely be challenges of with interpretation and implementation. For communities to engage fully, adequate financing is needed to build capacity for management and implementation. There is a growing emphasis on developing alternative and innovative financing for community-centred biodiversity initiatives. Capacity building is also required to ensure that community-operated eco-enterprises are effectively managed.

Government, conservation organisations, and other implementing agencies are ofte under-resourced and understaffed, and the adoption of a new, complex conservation framework may create additional strain on existing resources. It is therefore important to ensure that support and capacity building for the relevant stakeholders are provided. Also, it is important to cultivate public support for the OECM approach.

Opportunities for community-driven OECMs

Community-centred approaches to conservation have been evolving over the past few decades and are recognised by the CBD as important elements of a post-2020 global biodiversity agreement. Without community buy-in, conservation efforts stand little chance of success. OECMs seek to address this by engaging and partnering with local people, as well as ensuring landscapes are well-governed and managed in ways that deliver long-term, in-situ socio-economic solutions for communities and landowners.

As eyes on the ground, communities play an important role in wildlife monitoring. They are also integral to the ongoing protection of biodiversity and water resources. Communityowned land makes up a large proportion of land worldwide and community participation in conservation efforts is therefore critical. Engaging communities to actualise the socioeconomic benefits related to their land will encourage better stewardship of land and the associated biodiversity. The OECM framework creates an enabling environment for people living adjacent to protected areas to realize the potential socio-economic benefits that may come with preserving ecosystem services. OECMs facilitate the inclusion of a diverse range of stakeholders who are contributing to area-based conservation.

It also provides an opportunity for stakeholders (including traditional authorities, government, business owners and conservation agencies) to collaborate to find mutually beneficial solutions to biodiversity preservation and restoration. OECMs offer an alternative governance structure to attract long-term conservation finance, supporting nature-based economies that bring economic benefits to the communities.

Ultimately, the increasing recognition of OECMs may help engage a diversity of actors in local-to-international conservation processes and improve linkages between equitable conservation and effective conservation outcomes.

Conclusion

When managed effectively and implemented in close collaboration with local communities, OECMs can provide both biodiversity and development benefits. OECMs provide an innovative approach to conserving biodiversity through building win-win partnerships between communities, government, protected area managers and the private sector. African governments need to strongly advocate for the increase of these communitydriven management areas in both their national biodiversity plans, as well as their local economic development plans. A common African-driven agenda will assist in highlighting the importance of this approach at an international level, guiding the long-term implementation of sustainable finance, capacity support and the necessary regulatory tools.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for this publication.