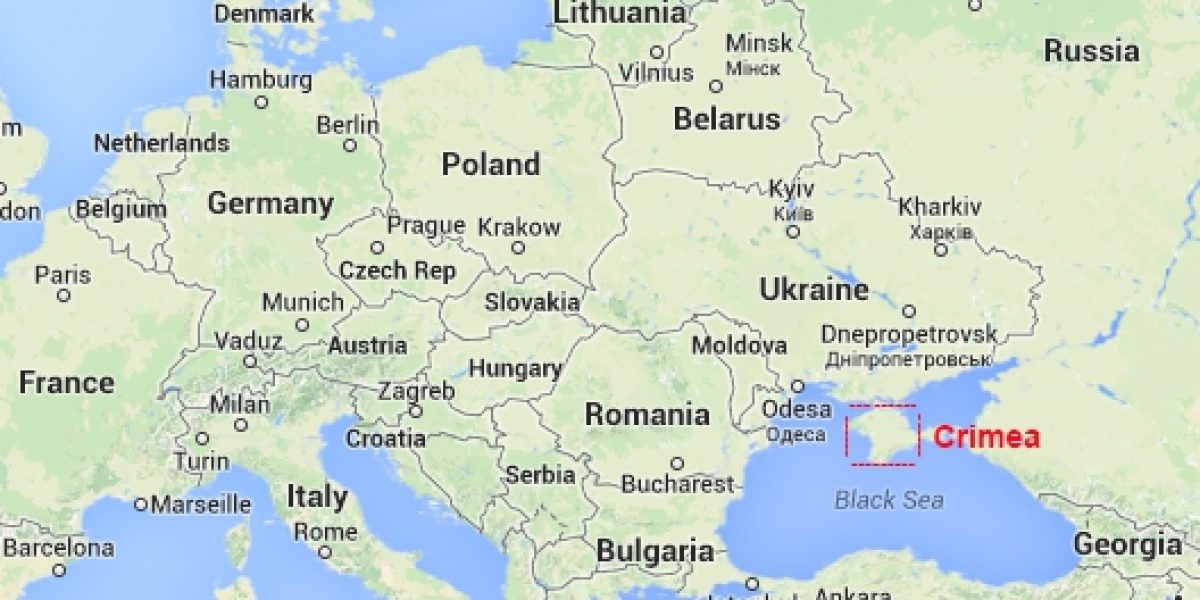

Bulgaria is still the poorest European Union country, but its fortunes have improved exponentially since it joined the EU. This makes the recent events in the Crimean Peninsula unfortunate. By leaving Ukraine, Crimea has missed a window of opportunity to benefit from Ukraine’s closer association with the EU.

However Russia was always going to stand in the way of Ukraine’s attempt to join the EU considering that it continues to make subtle overtures towards its breakaway states at diplomatic level.

During my time as South Africa’s ambassador in Sofia, which ended last year, I became very friendly with the Russian ambassador to Bulgaria, Yuri Issakov. He was a big bear of a man and at every cocktail reception – there were several every week – he would gather around him all the ambassadors of countries formerly members of the Soviet Union: Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, even Georgia – none, needless to say, members of the EU.

When I remarked on this he said he had to make sure “the brothers” stuck together. They were all men. I was left with the distinct impression that their separation was flimsy. They all deferred to Yuri in the sense that they would never have refused to join him. I suppose he was actively carrying out policies of his President Vladimir Putin.

Last September I visited Yalta and Sevastopol in the Crimea. While we were shown the Russian fleet from a distance and told where the silo containing its submarines was, there was little evidence of pro-Russian ideology. However the Russian heritage in the form of monuments, palaces and museums was everywhere to be seen. The presence of the Russian fleet was welcomed by the Ukrainians we met as a job creator and boost to the economy.

Ironically, in the light of subsequent events, we were unable to visit the famous Livadia Palace in Yalta where the conference between Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt took place in 1945. This was because a conference between leaders of the European Commission and the Ukraine government about the conditions for Ukraine’s entry into the waiting room for EU membership was taking place there. This was subsequently torpedoed by their then President Viktor Yanukovych, which in turn sparked off the original protests in Kyiv which led ultimately to his overthrow.

Three years before that in August 2010 we had visited Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, as guests of my colleague there, Ambassador Dries Venter. In contrast to the relaxed resort towns of the Crimea, Kyiv is a very large and grand city laid out on an imperial scale on the banks of the Dnieper River.

As we wandered around the capital, Dries’ accounts of how life worked there made your hair stand on end. Most of the ambassadors lived in apartment blocks in the city, preferably with a friendly oligarch in the penthouse so that the lights stayed on and the water did not suddenly dry up. Living in a self-standing villa even as a diplomat was too risky since, if an oligarch suddenly fancied it, men in black SUV’s would suddenly arrive and explain that it might not be healthy for you to stay on. The oligarchs ruled more or less and the rule of law was minimal.

President Yanukovych had jailed his predecessor Yulia Tymoschenko on the flimsiest of pretexts. None of this could even remotely have happened in Bulgaria during my time there. Of course Yanukovych has now fled to Russia – more evidence of a damaged if not broken democratic and legal system.

During that trip Dries arranged for us to visit Chernobyl. The visit itself was extraordinarily macabre and horrifying, not the least because of the inordinate delay by the Ukrainian government and their French contractors in the placing of a new dome to seal off Unit 4 where the cracked concrete shell poured over it in 1986 when the meltdown occurred, because it is drastically leaking radiation. Our guide’s dosimeter read 569 just outside the viewing tower.

I was also amazed to see water melons and other fruit being sold on the side of the road just outside the 30 km exclusion zone surrounding Chernobyl. Ukraine, I felt, was definitely the wild East. This too could never have happened in the EU.

Upon our return to Bulgaria, we felt happy to be back in far more modest Sofia at the end of that long weekend. My husband and I both had the feeling: thank goodness we’re back in the EU, where there are rules, norms and standards of governance. Hopefully the new Ukrainian government will eventually fulfill its country’s ambition to be part of the EU.

Bulgaria, together with its northern neighbour Romania, became a member of the EU at the beginning of 2007. It had joined NATO in 2004. Both these initiatives commenced during the Prime Ministership from 2001-2005 of Simeon Saxe Coburg Gotha, former heir to the throne of Bulgaria (he is the son of Tsar Boris III, who was murdered during the second world war, and was exiled to Spain aged 6 when the communists took over in 1945).

Since joining the EU vast amounts of Euro’s have flowed in, mainly for infrastructure upgrades and improvements to the institutional framework of their legal and administrative systems.

At first a lot of this money was stolen (Bulgaria still features even lower than SA on the corruption index of Transparency International). However, after a centre-right government took over in 2009, things changed for the better. The EU introduced a monitoring mechanism consisting of six-monthly report cards to the European Commission on how Bulgaria was performing.

There were even sanctions for non-performance. For instance, the EU has still not allowed Bulgaria to join the Schengen visa zone, arguing that although Bulgaria has fulfilled all the technical requirements relating to border control, not enough had been done to free the judiciary from systemic corruption. The same applied to Romania.

These negative report cards were hugely influential in persuading Bulgaria to introduce a far more transparent process for appointing judges, among other things. The EU ambassadors became a monitoring group for this and were particularly influential, with the government giving them regular special briefings, to the extent that we introduced a regular monthly lunch for what we called in UN –speak, the “non-group” so that they could brief the rest of us about what was going on. My overall impression after four years in Bulgaria is that EU membership has been hugely beneficial for the country and so this could have been the fate of the Crimean Peninsula.