How the COVID shock has impacted Africa’s food security

An assessment by the World Food Programme (WFP) indicates that in 2020 COVID-19 may have added up to 132 million undernourished people in the world1World Food Programme, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) Report 2020 (2020). https://www.wfp.org/publications/state-food-security-and-nutrition-world-sofi-report-2020.

Africa, where the number of undernourished people is growing faster than in any other region of the world, was estimated to have reached more than 250 million undernourished people as the pandemic compounded the effects of climate shocks and conflicts which were already causing hunger in many parts of the region2The causal composition of food crisis shifted significantly between 2019 and 2020 away from extreme weather events (locusts in the Horn of Africa, cyclones in South-eastern Africa) towards economic deprivation (69% increase) and civil / border wars (29% increase) notably in eastern DRC, north-eastern Nigeria and the Horn of Africa..

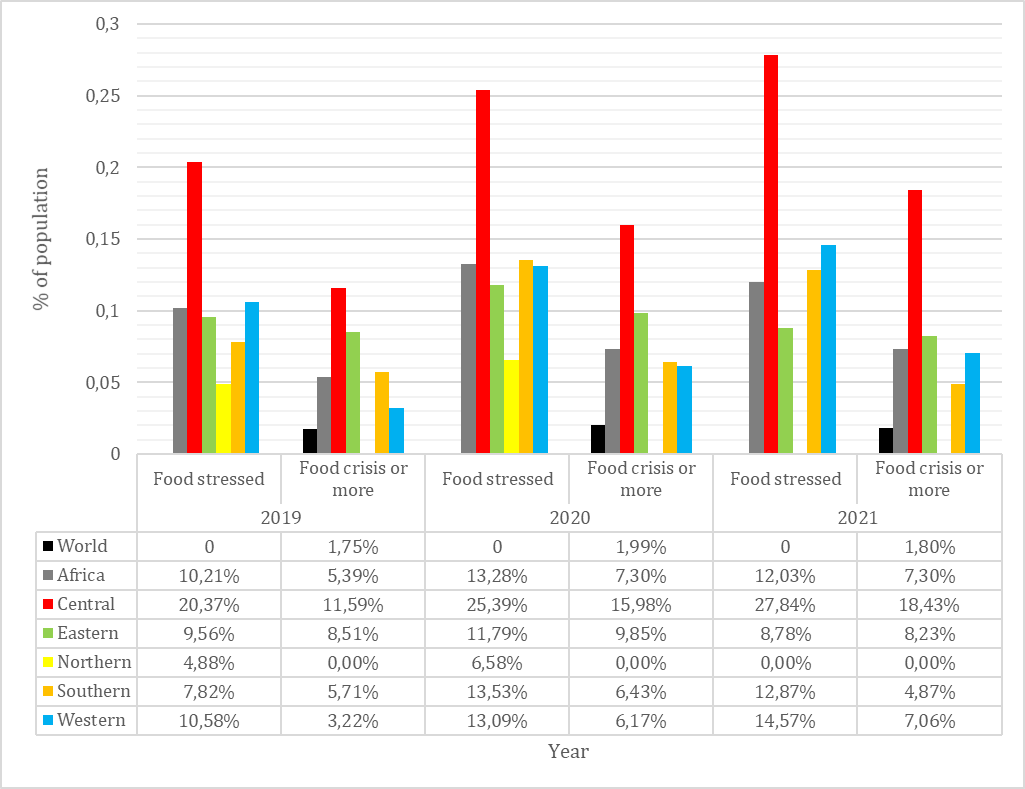

The further WFP reports that the proportion of Africa’s population that is food stressed (ie. all income used in purchasing food) increased from 10.2% in 2019 to 13.3% in 2020 and only partially recovered to 12% in 2021 (Figure 1).

Additionally, the proportion that is in food crisis – those selling core assets for food – and in food emergency or catastrophe increased from 5.4% to 7.3% following the Covid shock3Food Security Information Network (FSIN), “Global Report on Food Crises – 2021”, Rome, 5 May 2021, World Food Program. This threatens to push these households into long-term poverty and ongoing food insecurity.

Within Africa, upper-middle income countries including South Africa and the Maghreb nations proved most vulnerable to COVID-shock induced food insecurity, as their economies faced recessions of 6 to 9 percent in 2020.

These more diversified, industrialised economies are more tightly linked into global supply chains and hence more widely and deeply impacted by trade disruptions. South Africa faced 25% food stress and 16% food crisis, well above the African average.

This can be attributed to the relatively greater vulnerability to loss of formal sector employment (85% of the labour force) and lack of access to productive agricultural land.

Lower-middle income economies such as those from the East African Community, Nigeria, Benin, and Senegal, were less severely impacted by the COVID shock. Most of these economies decelerated significantly in 2020, many recording low growth.

Since employment status in these countries is much more skewed towards informal and domestic employment which on average constitutes 85% of the labour force, the impact on poverty and food insecurity was less severe, albeit on a much broader base of structural income poverty, compensated though by a more widespread access to land use rights.

The level, rise and degree of food insecurity is most pronounced in Africa’s poorest regions, notably Central Africa. Some of these areas are prone to extreme weather events particularly in the Sahel, others are caught in intermittent civil and border war eruptions (DRC, Horn of Africa, NE Nigeria) and all have been exacerbated by disruptions of regional supply chains from the core, middle-income agricultural and industrial economies.

Figure 1. Proportion of population by food security status in African regions, whole of Africa and the world

The suppression of domestic protectionist impulses

Access to fertile, rural, agricultural land is an important factor in enabling resilience to the effects of economic disruptions on food security. Agricultural production (and trade) is one of the few sectors that grew during the COVID shock of 2020 in Africa.

Consumer demand for food is income inelastic and was therefore sustained, whilst some suppression of aggregate demand was redirected into agricultural commodities.

On the supply-side, extreme weather events are the main determinants of food output in the region and these have subsided since 2019. However, with other regions within the continent facing COVID induced food insecurities, the role of intra-continental free trade becomes more prominent to facilitate reallocation of food from those that have it in abundance to those that need it.

Without free trade, consumer and producer choices are narrowed due to lack of diversification of sources and markets. In Malawi for instance, food production in 2020 registered a 5.1% increase yet the government maintained its maize export ban which had been in place since February 2018 to enhance its own food security.

This, coupled with low domestic prices offered to farmers, has introduced market inefficiencies that result in income losses for the farmers, and have contributed to food insecurities on a continental level as countries that needed Malawi’s surplus maize could not access it.

Free trade also increases competition and suppresses monopolistic pricing behaviour which can run contrary to government impulses to streamline internal operations by limiting the number of public or private actors to whom it grants monopoly and monopsony rights.

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which was launched in 2018 and became operational in 2021, is designed to promote intra-African trade and industrialisation on the continent, which will help address the continent’s food security issues.

However, recessions are often used to justify protectionist impulses and the current crisis provides a test of commitment by parties to the agreement. Compared to the previous global food crisis of 2007-08, cereal export quotas by major food-exporting nations and additional sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) standards, were few and limited in duration.

Several major nations including Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt released cereal reserves, but Algeria, Angola, Mali and Sudan imposed export restrictions to replenish their stocks, whilst Malawi retained its 2018 export ban. South Africa exempted basic foodstuffs from both import duties and VAT, and duties were suspended by Morocco, Kenya, and Chad. In general, recognition of the pro-cyclical consequences of beggar-thy-neighbour policies prevailed4Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), “Agricultural trade and policy responses during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020”, Rome, 2021.

Building resilience through free trade negotiations

AfCFTA negotiations have made some progress which promises enhanced resilience to future food shocks that will affect the continent. As of October 2021, 38 of 55 member countries had deposited their ratifications, and 41 had submitted their tariff schedules.

Negotiations on rules of origin (RoO) and tariff reduction schedules for trade in goods are ongoing, albeit delayed due to COVID-19 disrupting negotiations. Rules of origin for trade outside existing regional agreements are being negotiated sector by sector starting with agricultural products which has been completed, and subsequently moving to agro-processed goods which have more complex origination rules to determine the degree of local or African content eligible for preferential tariffs5Trade Law Centre (tralac), “AfCFTA Rules of Origin”, Factsheet, Stellenbosch, May 2021.

The tariff offer received from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) as Non-Least Developed Countries (NLDCs), abides to a 5-year phase out of tariffs on non-sensitive goods covering 80% of product lines. Offers from the East African Community (EAC), Central African Economic and Monetary Union (CEMAC), and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) respectively cover 71%, 100% and 90% of product lines, with tariffs phased out over 10 years6Trade Law Centre (tralac), “AfCFTA Comparative analysis of tariff offers, Factsheet, Stellenbosch, March 2021.

Northern Africa and the remainders of Southern and Eastern Africa have still to determine their tariff offers. This is due either to their immaturity as Preferential Trade Areas (rather than customs or monetary unions), or (b) their overlapping membership of the larger free trade agreements including the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

Where tariff offers are not forthcoming, individual countries continue applying their agreed Most Favoured Nation (MFN) rates applicable as of May 2019.

The AfCFTA will likely have less preferential common external tariffs (CET) on agricultural imports from the rest of the world. The CETs already set by the various Regional Economic Communities (RECs) reflect an agricultural development policy priority in the Least Development Country (LDC) groupings to protect domestic food producers with high import tariffs (usually between 25% and 45% of value) and exclusion from tariff offers through declaration as sensitive goods.

Exceptions are made for cereal staple imports from the rest of the world where food crises, emergencies or catastrophes are more prevalent. Trade protection of agricultural producers is less apparent in SACU where tariff barriers are more likely on highly processed, beneficiated or manufactured items.

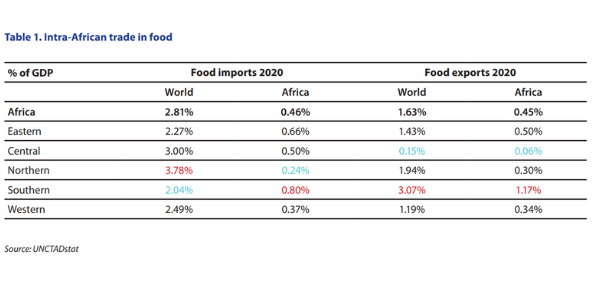

With intra-African food trade lower than 0.5 percent of GDP (Table 1), the AfCFTA is poised to increase food trade volumes and therefore improve Africa’s resilience to food shocks. Africa’s total food trade deficit against the rest of the world equalled 1.18% of its GDP in 2020.

Removing the trade restrictions within the continent through well-functioning AfCFTA will replace some of these imports from the rest of the world with intra-African trade. This will facilitate the development of the African agriculture sector and improve the continent’s food resilience in the process.

The ensuing stages of trade liberalisation within AfCFTA involve acting on the information received from complaints about non-tariff barriers. Whereas international SPS and technical barrier to trade standards can serve as benchmarks, the institutional capacity to monitor and implement may be less credible.

This can be tackled through focused aid-for-trade schemes aimed specifically at developing these capacities, notably Simplified Trade Regimes with reduced RoO and PSP requirements for low value consignments. These enable legalisation of informal cross-border trade, arguably the most effective market-based mechanism for redistributing food.

African governments must also ensure that trading rules extend to all policies intended to ensure domestic food security, that may blur the boundaries between support and [contestable] protection. These include domestic agricultural input subsidies and export quotas to restore food banks.

Furthermore, there are several agricultural development policies that include local content and ownership requirements, government procurement of food through preferred suppliers, surtaxes on imported foods, and government owned distribution channels that open themselves to dispute resolution.