Recommendations

- The G20 leaders, notably South Africa, should promote greater participation of African and other developing countries in the Inclusive Framework.

- The G20 needs to address the unequal impacts of the agreement and extend the digital services tax permission to all countries until the new rules come into effect.

- The G20 must advocate the development of the multilateral convention within the UN to ensure that countries participate on an equal footing.

- The G20 should make clear commitments to ensure that countries have sufficient funding and technical capacity to implement the required policies.

- Signatories to the Inclusive Framework must reconsider lowering the threshold for companies that are eligible for profit reallocations to improve revenue mobilisation for developing countries.

- Signatories to the Inclusive Framework have to ensure that the mandatory dispute mechanism is equitable, fair and effective.

- Signatories to the Inclusive Framework must ensure that the agreement is driven by consensus rather than political pressure.

Executive summary

The current global taxation framework is extremely fragmented and filled with inconsistencies which allow multinational corporations to pay less than their fair share of taxes in the jurisdictions in which they operate. Part of the problem is that businesses are liable to pay taxes where they have a physical presence or permanent establishment (headquarters). However, digital companies that can operate virtually across multiple countries avoid paying taxes in these countries, despite generating revenues from their activities there. Furthermore, countries can autonomously determine their corporate tax rates. In an effort to attract foreign investment and capital, countries can lower their tax rates, thus becoming preferential regimes or even tax havens. This triggers a chain reaction from other countries which, to protect their own revenues, also lower their tax rates, prompting a race to the bottom. The G20/OECD Inclusive Framework is a multi-country platform that was established to negotiate the standards of a global taxation system that will curb harmful tax competition and tax avoidance by multinational companies, especially those that operate digitally. In July 2021, the Inclusive Framework published the Two-Pillar Solution to Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, with 136 countries as signatories. However, a number of African and other developing countries were not part of the Inclusive Framework, with some countries refusing to sign the agreement on the basis that the G20’s proposed minimum corporate tax rate of 15% is too low. Some tax justice campaigners and other developing countries have rejected the deal, claiming that it too narrowly benefits rich countries while also ignoring the key considerations that were raised by G24 members. For the agreement to be successful and an effective, global solution to the problem of tax avoidance, the Inclusive Framework and G20 must respond to the grievances of developing countries and attach equal priority to their economic needs.

Introduction

The ability of countries to autonomously set their corporate tax rates as part of their sovereignty has inadvertently given rise to harmful tax competition and widespread tax avoidance. Under the status quo, some countries have gradually lowered their corporate tax rate, while others have completely eradicated corporate tax, to attract foreign investment and capital. This practice has resulted in the countries concerned becoming preferential tax regimes or tax havens, which indirectly forces other countries to also lower their tax rates so that they can compete for capital. In addition, some tax rules and multinational digital businesses allow companies to artificially shift their profits to low- or no-tax jurisdictions (profit shifting), thus drastically reducing their tax liability and leading to the erosion of countries’ tax base. This phenomenon has enabled multinational corporations and wealthy individuals to pay little to no tax, thus depriving countries of up to $247 billion in revenue which is crucial for social and economic development.1Global Alliance for Tax Justice, ‘State of Tax Justice 2020: Tax Justice in the Time of COVID-19,’ https://www.globaltaxjustice.org/en/latest/427-billion-lost-tax-havens-every-year.

Globally, African countries and other least-developed countries (LDCs) experience the greatest loss of would-be tax revenues as a share of gross domestic product (GDP).2Alex Cobham and Petr Janský, ‘Global distribution of revenue loss from corporate tax avoidance: Re-estimation and country results,’ Journal of Internal Development 30, no. 2 (2018): 206–232. This disparity is the result of a number of factors, such as the historically weak taxing rights of African countries under bilateral tax treaties and the weaker financial and technical capacities of tax administrations in Africa. African countries also have much smaller tax bases – evidenced in their lower tax revenues-to-GDP ratio (tax ratio) – compared to their European counterparts. In 2011, more than 20 African countries maintained tax ratios below 15% – in contrast to the G20 (excluding Russia, India and Saudi Arabia for which data was unavailable) and OECD countries which maintained averages of 27.8% and 32.2% respectively, highlighting the primacy of these revenues.3OECD. Global Revenue Statistics Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RS_GBL#

Taxes are an essential revenue source, especially for countries with high levels of poverty and inequality as governments rely on tax revenues to provide basic public services such as healthcare, education, utilities, infrastructure and social programmes. Thus, reduced capacity to mobilise these revenues impairs countries’ ability to provide basic services and to achieve financial developmental goals, such as those relating to climate change adaptation and mitigation as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Against the backdrop of the devastating impact of COVID-19 on economies globally, the developmental impact of tax avoidance is particularly worrying.4‘ATAF: How COVID-19 has impacted Africa’s tax landscape,’ CNBC, March 9, 2021, https://www.cnbcafrica.com/2021/ataf-how-covid19-has-impacted-africas-tax-landscape/. Post-COVID-19 recovery requires effective and sustainable tax revenue mobilisation. This can be accelerated through reforms to global tax standards, which would shield vulnerable countries from the risk of tax avoidance. This means that tax rates and thresholds must be set at levels that allow countries to meet their various developmental objectives, as well as support post-COVID-19 economic recovery efforts.

The G20/Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) has presented an opportunity to drive a multilateral process of negotiating new global tax standards and rules that will curb harmful tax competition and avoidance. However, while much progress has been made, there remain worrying aspects to the Framework agreement and the accompanying process, such as the low representation of African countries, the lack of confidence in the process to adequately protect poorer countries against significant revenue losses, and the inclusion of provisions that are unsuitable for poorer countries whose taxing rights are already compromised – to name a few. As a result, some global tax justice campaigners have called on developing countries to reject the tax deal on the grounds of some of these problems.5Farah Nguegan, ‘African Civil Society Organisations Call for Rejection of OECD/G20 Global Tax Deal,’ Tax Justice Network Africa, October 29, 2021, https://taxjusticeafrica.net/african-civil-society-organisations-call-for-rejection-of-oecd-g20-global-tax-deal/.

In light of the above, there is an urgent need to increase the representation of African countries in the Framework through diplomatic interventions, to boost the confidence in the new standards and acknowledge the different capacities and resources that are needed to implement the agreement, and to ensure that the new standards are applied in a fair, equitable manner by all countries. It is imperative for the G20/OECD Inclusive Framework to address the key challenges and grievances that have been articulated by developing countries and campaigners, and to facilitate an approach that responds to the unique concerns of African countries and encourages their increased cooperation.

Multilateral efforts to curb tax avoidance

In 2013, the UK hosted the G8 Summit which focused on trade, transparency and taxation and put tax avoidance, specifically through base erosion and profit shifting, under the spotlight. Acknowledging the prevalence of tax avoidance, the G20 called on the OECD to assist in developing the BEPS Project to find collective solutions to limit tax avoidance by multinational companies. The key priorities of the BEPS Guidelines were to eliminate double taxation as well as double non-taxation of multinational companies, introduce more fairness and effectiveness into the existing international taxation rules, and ensure more transparency and coordination in tax practices globally.6Pascal Saint-Amans, ‘History of the G20 & Taxation,’ Interviewed by OECD Tax, June 2019. In the past, some countries, such as France and the UK, attempted to unilaterally curb tax avoidance through a digital services tax on the revenues derived from the activities of users of search engines, social media platforms and online marketplaces.7Annabelle Dickson, ‘UK to introduce “Google Tax” in 2020,’ Politico, October 29, 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/uk-to-bring-indigital-services-tax-in-2020/. These policy moves were seen as controversial because they were tabled in the midst of negotiations for new international tax standards to tackle this problem. Hence, the G20’s 2021 Rome Summit Declaration makes reference to international taxation in Clause 32 and emphasises the need for an inclusive multilateral solution to tax avoidance, and the global implementation thereof by 2023.8G20 Research Group, ‘G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration Rome 2021’ (University of Toronto, 2021), October 31, 2021, http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2021/211031-declaration.html. The Africa Standing Group (T20 ASG) – a network of think tanks from across Africa and G20 countries – has provided cross-regional policy research and capacity building to promote tax cooperation and financial transparency between developing countries and G20 countries.9German Development Institute, ‘6th International Workshop on Domestic Revenue Mobilisation,’ https://www.die-gdi.de/en/events/details/mobilising-resources-for-development-the-role-of-international-cooperation-in-tax-matters/

Other attempts to tackle tax avoidance include (bilateral) tax treaties. However, there has been criticism of the unequal nature of tax treaties as some experts have highlighted patterns of bias in the treaty outcomes, mainly in respect of taxing rights, between OECD countries and developing countries over time.10Martin Hearson, ‘Measuring Tax Treaty Negotiation Outcomes: the ActionAid Tax Treaties Dataset,’ International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) Working Paper 47, Institute of Development Studies, https://www.ictd.ac/publication/measuring-tax-treatynegotiation-outcomes-the-actionaid-tax-treaties-dataset/. Several proposals have been made to remedy these imbalances, such as the OECD-led 2017 Multilateral Convention and the Multilateral Instrument or ‘MLI’11OECD, ‘Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent BEPS, Tax Treaties,’ https://www.oecd.org/tax/treaties/multilateral-convention-to-implement-tax-treaty-related-measures-to-prevent-beps.htm. which standardised important anti-avoidance mechanisms such as country-by-country reporting (CBCR) and automatic exchange of information, among others.

Several intergovernmental bodies, such as the European Union (EU) Commission, the UN Economic and Social Council’s (ECOSOC) UN Tax Committee, the G2412The G24 countries are Algeria, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Ecuador, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Iran, Kenya, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Syria, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela (and China as a special invitee). and, more recently, the G77 plus China, have also contributed policy tools to curb tax avoidance globally. The G24 has been one of the main advocates of global tax reform to address the inequalities between wealthy and poor countries and to ensure that negotiations take place on the neutral ground of the UN where all countries have an equal say.13Ehtisham Ahmad, ‘Political Economy of Tax Reform for SDGs Improving the Investment Climate; Addressing Inequality; Stopping the Cheating,’ G-24 Working Paper, https://www.g24.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Political_Economy_of_Tax_Reform_for_SDGs.pdf.

G20/OECD Global Tax Agreement and its implications

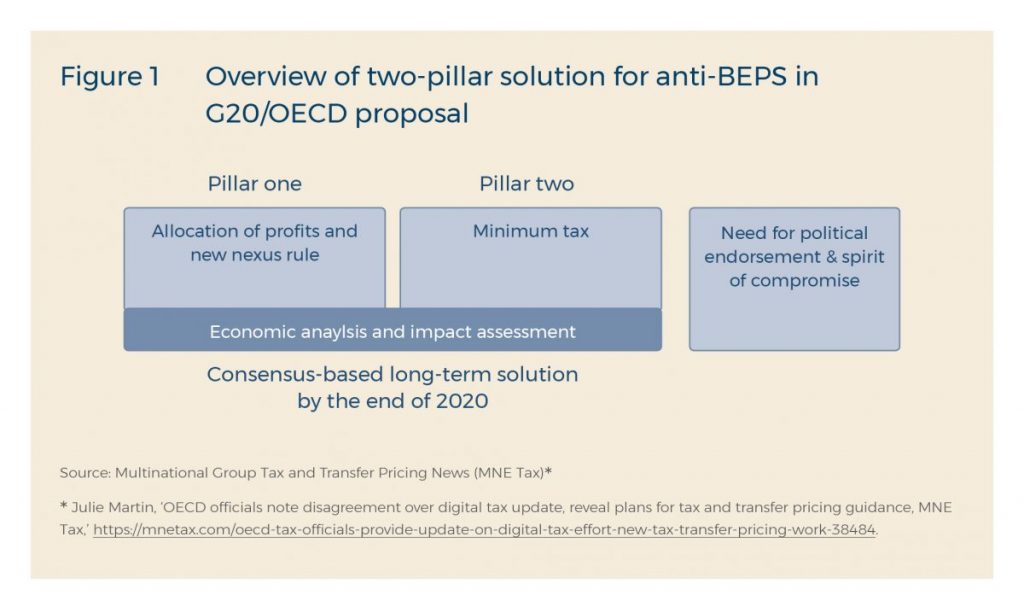

The key provisions of the Global Tax Agreement include the scope of companies and sectors to be covered, the percentage of profits to be reallocated, the rollback of unilateral measures and an arbitration mechanism aimed at conflict resolution. The agreement seeks to introduce a new taxing right in Pillar One which is focused on reforms to the existing nexus and profit allocation rules, while Pillar Two is focused on a global minimum tax. In addition, the two-pillar approach adds new elements to international taxation, such as limited formulary apportionment, the global minimum corporate tax rate, multilateral dispute resolution and the allocation of taxing rights through a multilateral agreement.14Global Tax Justice, OECD-led Inclusive Framework: Behind Closed Doors and Outside the UN, OECD-led Inclusive Framework: Behind Closed Doors And Outside The UN | Global Alliance for Tax Justice (globaltaxjustice.org).

Digital taxation challenges need to be addressed, including whether and how to tax businesses that do not have a physical presence (such as headquarters) in a country. In the past, physical presence was used as an indicator of economic activity. However, the transnational nature of the digital economy and increased mobility of capital and frequency of cross-border transactions have enabled businesses to be active in a country without a physical presence. Pillar One provisions aim to reallocate taxing rights in the absence of a physical presence, although the challenge will be setting a threshold and scope for companies that are eligible to be taxed by certain jurisdictions.

Developing countries experience disproportionate losses through tax avoidance and the G20/OECD deal

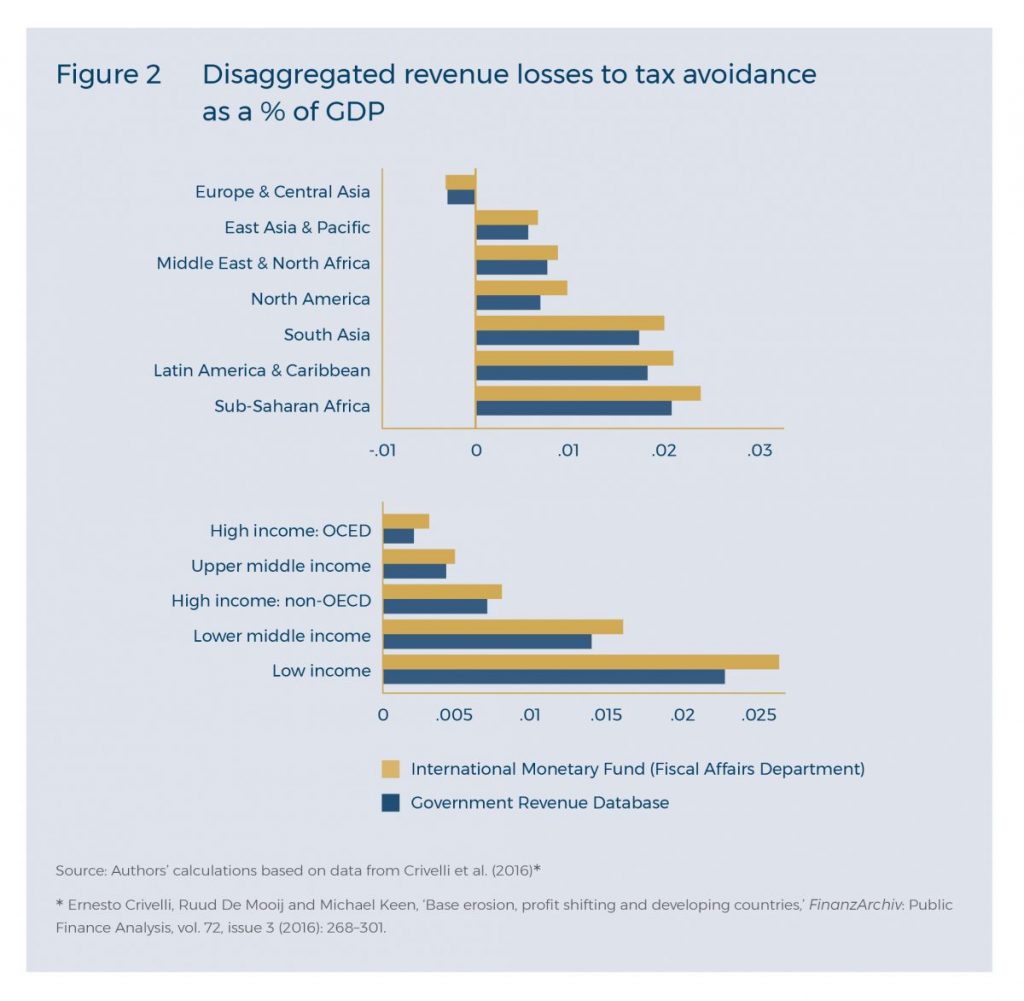

Developing countries have been found to be disproportionately exposed (compared to wealthier countries) to the risks and adverse effects of tax competition and avoidance. While the World Economic Forum (WEF) reported that the US and China sustained the largest annual losses in revenue to tax avoidance overall – $188 billion and $66.8 billion respectively – a 2018 study using International Monetary Fund (IMF)-derived data revealed that developing countries experienced greater actual tax revenue losses as a share of GDP.15Alex Cobham and Petr Janský, ‘Global distribution’. This disparity can be as large as 5%–8% of GDP, as found in countries like Guyana, Chad, Guinea, Zambia and Pakistan, among others. This is in contrast to the negligible proportions of 0.61%–1.06% of GDP found in countries with larger economies and more substantial means, such as Germany, France and the People’s Republic of China.16Alex Cobham and Petr Janský, ‘Global distribution’.

Furthermore, the fact that developing countries depend more on corporate taxes and income taxes than developed countries highlights the need for developing countries to have a greater say in the agreed minimum corporate tax rate. This is evident in the fact that Europe has the lowest regional average corporate tax rate at 19.99% (24.61% when weighted by GDP), while conversely, Africa has the highest regional average rate at 28.5% (28.16% when weighted by GDP).17Elke Asen, ‘Corporate Tax Rates around the World, 2020,’ Tax Foundation, 2020-Corporate-Tax-Rates-around-the-World.pdf (taxfoundation.org). Figure 2 illustrates the average losses per GDP by region and by income (tax revenues) as a percentage of GDP for each region.

Nigeria’s refusal to sign the agreement was on the basis that its own corporate tax rate – currently 30% – is far more beneficial to the country and so endorsing the deal would be a huge setback. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation and its exclusion from the deal would seriously compromise tax cooperation. Similarly, Kenya was reluctant to sign because its officials were unwilling to repeal its recently adopted digital services tax (DST), believing that the new standards would significantly shrink these revenues. In contrast, Ireland’s initial reluctance to sign the agreement was based on its desire to maintain its 12.5% tax rate, the key to the country’s competitiveness for years, according to Irish Minister of Finance, Paschal Donohoe.18Cliff Taylor and Ellen O’Riordan, ‘Ireland one of 9 countries to hold out on signing OECD global tax deal,’ Irish Times, July 1, 2021, https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/ireland-one-of-9-countries-to-hold-out-on-signing-oecd-global-tax-deal-1.4609129.

These cases reveal that a global tax agreement requires compromises from all countries involved, as they will be giving up a degree of their sovereignty for the common good of improved tax cooperation. However, some developing countries will be more harshly impacted by the compromises made. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all participants in the negotiation process to ensure that the most vulnerable are given enough capacity to become self-sufficient. A global tax deal must take these inequalities seriously and measures should be adopted to mitigate the further marginalisation of affected countries.

Criticism of the Inclusive Framework agreement

Much of the criticism of the agreement has come from developing countries, who are significantly underrepresented in the Framework. While the OECD boasts 136 participating countries and jurisdictions, representing more than 90% of global GDP, this does not excuse the dismal representation of countries with smaller, less-developed economies. Worryingly, only 23 out of 55 AU members have participated in the project, leaving more than half the continent excluded from the negotiations. This casts doubt over the representativeness of the agreement and, consequently, the fairness of the provisions to account for the economic differences between countries. This dynamic has undoubtedly fuelled perceptions that there is a gross lack of proportionality in the priorities raised by developing countries compared to those of the developed nations.19Martin Guzman, ‘A global tax deal: A victory for whom?’ Independent Commission for the Reform of International Tax Cooperation (ICRICT)/G24. (2021), Online Webinar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0Nxrw0ZmIY&ab_channel=ICRICT.

Even among the participating developing countries, the context of a G20/OECD-led initiative has triggered debates about the absence of a neutral or equal footing in negotiating power as well as concerns that some developing countries may have signed the deal because of political pressure and fear of being excluded from multinational corporate tax revenues altogether.20African Tax Administration Forum, ‘A new era of international taxation rules – what does this mean for Africa?’ International taxation rules – What does this mean for Africa? (ataftax.org). To address these issues, the G24 countries have been calling for the negotiation of a global tax agreement at a neutral organisation, such as the United Nations, or the establishment of a new, independent global tax institution with the power to enforce compliance. The underlying inequalities pose a threat to the current deal as some members of the African Forum for Tax Administration (ATAF) have sought a suggested approach to drafting legislation on digital sales tax (DST) services to pursue as an alternative option should an agreement not be finalised. A DST provision, which would enable countries to charge tax on digital transactions, could build public confidence in the fairness of the tax system and enhance tax morale, while boosting broader voluntary tax compliance.21African Tax Administration Forum, ‘ATAF publishes an approach to taxing the digital economy,’ October 1, 2020, https://www.ataftax.org/ataf-publishes-an-approach-to-taxing-the-digital-economy. It would thus be in the interests of all countries to take these grievances seriously.

Another concern is that the scope of the companies to which the deal applies is favourably biased towards the US and will apply narrowly to only 100 companies rather than several thousand.22Matthew Gbonjubola, ‘Nigeria can’t back current OECD Pillar One, delegate says,’ interview by Kevin Pinner, August 2021. The minimum tax rate would only apply to companies with annual sales of at least €750 million ($872 million). The majority of these companies are US-based ‘tech’ companies, which are among the few to have reached this level of turnover. Lowering the turnover threshold would make more companies eligible for profit reallocation, thus granting other countries the opportunity to collect taxes from a bigger pool of companies. Some countries – the US, UK, France, Italy, Spain and Austria – have further skewed the benefits of this agreement in their favour by negotiating a side deal that allows them to retain their DSTs, while other countries will be expected to repeal them. This affords these countries additional protection for their digital tax revenues for the next two years until the global deal comes into effect.

Countries such as Argentina have criticised the lack of transparency of the methodology used to perform the impact assessment of the agreement’s instruments.23Martin Guzman, ‘A global tax deal: A victory for whom?’ Independent Commission for the Reform of International Tax Cooperation (ICRICT)/G24, October 7, 2021 (online webinar), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0Nxrw0ZmIY. The OECD claims that the new rules would result in an approximately 0.7% increase in effective tax rates across all jurisdictions. However, this methodology was created and finalised without the input of most developing countries and subsequently gave rise to scepticism. Consultation is an essential requirement for policy considerations and for achieving policy legitimacy and widespread buy-in.

The final point of criticism is related to the unequal implementing capacities of countries, particularly developing countries that also lagged in the implementation of the BEPS standards. Thus, the agreement must ensure that signatories are committed to improving countries’ collective technical and financial capacities to implement the rules to the prescribed global standards.

Conclusion: Considerations on the way forward

The international community has made considerable progress in working towards the elimination of tax avoidance, and the leadership of the G20/OECD Inclusive Framework has, alongside other organisations, contributed immensely to this project. This policy briefing has highlighted some of the key factors necessary for the successful implementation of the agreement, particularly the concerns that have been raised by developing countries and tax justice campaigners. At the centre of these concerns is the call for more transparency, equality and fairness in negotiations, greater participation of developing countries, and more responsiveness to the vulnerabilities of developing countries to the harmful impact of tax avoidance.

As things stand, the deal was finalised in October 2021, with 136 signatories. What remains is for signatory countries to enact domestic legislation to implement the new tax rules and formally approve a multilateral convention to be drafted by the OECD in 2022 and implemented by 2023. Although world leaders publicly endorsed the agreement at the G20 summit in Rome, more work needs to be done to sustain the momentum throughout the upcoming stages.

The key to a stronger global tax deal lies in the Framework’s ability to provide solutions that will work for the common good, rather than a select few. There is still ample time to address the concerns that have been raised and to ensure the legitimacy of the deal to all countries. Failure to do so will heighten the risk of alienating some of the key developing and emerging economies and prompting the unilateral adoption of alternatives, which will weaken global tax cooperation.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung for this publication.