Click here for a package of SAIIA materials related to foreign direct investment.

What is foreign direct investment (FDI)?

Foreign direct investment is understood as the acquisition of a lasting interest, usually with at least ten percent stake, in an enterprise operating outside of the country of domicile of the investor, with the purpose of gaining effective say in the management of the enterprise.

Source: Balance of Payments Manual: Fifth Edition (BPM5) (Washington, D.C., International Monetary Fund, 1993)

What types of FDI are there?

- Greenfield investment is a new investment expected to bring in relatively substantial inflows of FDI; new production capacity and employment;

- Brownfield investment is an investment into an existing facility geared towards improving or increasing its capacity, with a quick technology and skills spill-over effect;

- Mergers & acquisitions see inflow of FDI capital, but not necessarily new productive capacity; there are potentially spill-over effects with investment in better technology and higher productivity (the Walmart/ Massmart merger is an example this type of FDI);

- Joint ventures involve a strategic alliance between the foreign company and (usually) a local company with the view to doing business together.

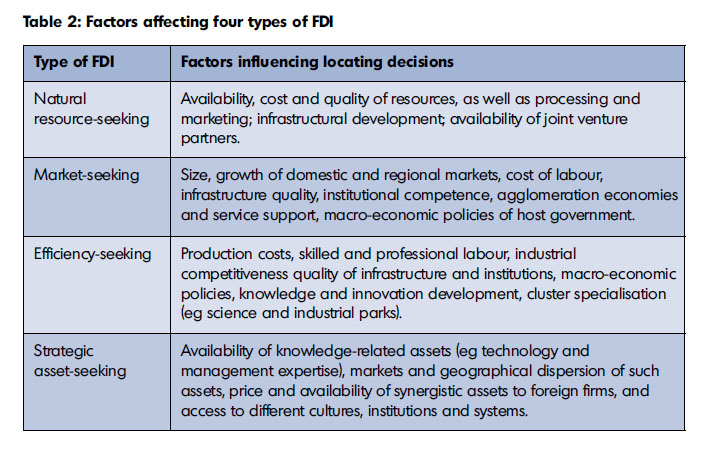

There are broadly-speaking four types of FDI represented by investor motivation:

Source: SAIIA Occasional Paper 105, South Africa’s Investment Landscape: Mapping Economic Incentives

Is FDI beneficial?

Empirical studies show that FDI typically generates economic growth in the host country especially through direct employment generation, or through linkages with suppliers, subcontractors and service providers. However, there is also evidence that FDI can have negative effects. FDI is found to be favourable to economic welfare of the host country only if appropriate conditions exist in the host economy. This includes adequate absorptive capacity for instance, new financial capital and new technologies in plants, as well as human capital. Also it is important that domestic businesses are not “crowded out” and are able to face up to foreign competition. Stated differently, market gaps filled by foreign companies are ideally over and above those that can and should be filled by home producers. This means that industrial policy – while staying within the precincts of the rules of the multilateral trading system – should also seek to prop up infant industries to the degree that they are competitive and do not distort competition.

Source: Lipsey and Sjöholm, 2005.

With the rise of multinational corporations, the complexity of supply and value chains for manufacturing and services has grown, spreading across countries and continents. Today, global value chains have enhanced the significance of FDI as a critical engine of trade and development, creating jobs, and promoting knowledge and technology transfers. In 2012, global GDP was USD$ 70 trillion, global exports in goods and services were USD$ 22 trillion, the global stock of FDI was also about USD$ 22 trillion, and global sales from FDI affiliates were USD$ 28 trillion. MNCs account for about 80% of world exports with half of this located in global value chains.

Source: The WEF Global Agenda Council on Global Trade and FDI.

As countries liberalise and reduce policy impediments to FDI, however, competition policy increasingly important factor in regulating markets, to ensure that regulatory barriers to FDI are not replaced by anti-competitive company practices. The inflow of FDI can have unintended consequences on an economy, including the development of hostility between foreign and domestic firms. It is therefore necessary to accelerate and sustain market economic reforms alongside policies aimed at liberalising FDI.

Source: SAIIA Occasional Paper 111, Perspectives on Trade, Investment and Competition Policy in South Africa

What has been the South African government’s economic strategy since 1994?

The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) launched by the ANC government in 1994 focused on the problems of lack of housing, a failing education, a jobs shortage, and health care system.

The Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) macroeconomic strategy was adopted by the Department of Finance in June 1996. It was a five year plan aimed at strengthening economic development, broadening of employment, and redistribution of income and pro-poor socioeconomic opportunities.

Most recently, the Zuma Administration’s New Growth Path, from which the National Development Plan: Vision for 2030 stems, sets out the government’s plan to increase employment and to develop a more equal society. The pivot of this plan is around massive investment in infrastructure and people through skills development, and better coordination with the private sector and a very strong union movement. As usual, the devil is in the detail and the implementation of this plan is yet to be realised.

The government supports its economic vision, expressed in the New Growth Path (NGP) released in December 2010, with two Industrial Policy Action Plans (IPAP 1 and 2). In addition, a relatively sophisticated investment promotion framework is in place, together with its nascent policy framework to manage the costs and benefits of inward FDI.

Finally, the authorities have put in place a package of incentives to foster the development of small and local businesses, to promote employment and competitiveness, and encourage FDI.

Source: The Department of Trade and Industry

What is the South African government’s approach to FDI?

Attracting FDI has been a cornerstone policy of post-apartheid economic policy. The government was keenly aware of the need to rebuild the country’s image with international investors after the isolation of the apartheid era, and a concerted effort was made to build an investment environment that was liberal and open. This culminated in South Africa entering into a flurry of bilateral investment treaties with capital-exporting countries. FDI is especially important because of the low domestic savings rate, which limits the scope of domestic investment financing.

South Africa is undergoing a significant transition in its approach to inward FDI. Increasing discontent over the apparently lacklustre results of a liberal approach to FDI has sparked a push towards an FDI regime aimed at extracting maximum domestic benefits from each investment. The change reflects a shift in mindset: from seeing FDI as beneficial in itself, to viewing FDI as beneficial only when it achieves certain policy aims. These aims include fighting rampant unemployment, creating inclusive growth and accelerating progress – key components of the National Development Plan.

South Africa is thus in the process of cancelling or allowing the expiration of various Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) accrued after the end of apartheid in the exuberant liberal phase. These BITS are set to be replaced by a single domestic investment regime that will offer various protections for investors, while allowing room to implement policies to redress economic inequality and meet domestic policy objectives. South Africa was not able to safeguard much policy space in its earlier BITs, especially in relation to black economic empowerment. As already noted, it has decided to carve out this policy space through a domestic statute. This is in line with in a global move towards third generation BITs. It should be stated however that the global move in reforming the system is manifest in new-generation BITs and not necessarily domestic statutes.

The Promotion and Protection of Investment Bill, which will make up the backbone of this domestic legislation, was released for public comment on 29 October 2013 by the South African government.

Experts agree that the Bill does not adequately address expropriation, nor is there specified recourse to international arbitration, protection which was contained in the now-cancelled BITs. On the positive side, the dti has progressed quite far along in the drafting of a new-generation BIT template. Analysts in this field remain hopeful that an early disclosure of this template BIT will alleviate fears concerning the dispute resolution issue in particular.

BBBEE and local content

While considered rational by many, the government’s greater focus on maximizing the domestic benefits of FDI, including implementing local and black economic empowerment partnerships, as well as local content agreements, does complicate the structuring of FDI transactions. Historically, most FDI into South Africa has come in the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&As), where the local firm is mostly equipped to comply with these requirements. Greenfield investment, which has been persistently weak into South Africa, would likely be more complicated – if much more desirable. Greenfield FDI would find South Africa attractive if it had a highly-skilled workforce, considering that it has a small market with low credit-worthiness.

What is the state of FDI in South Africa?

South Africa’s economy has been characterised by low national savings, and investment financed largely through more volatile portfolio flows rather than by longer-term FDI. Some long-standing political legacies such as widespread unemployment, high crime rates and generally low education and skills development, have proved difficult to shake off in the 20 years since the present African National Congress (ANC) government took office. A highly developed and competitive formal economy sits alongside a poor and informal economy.

South Africa’s FDI has been volatile, is on average lower than comparable developing countries despite positive changes in its investment climate since transition to democracy. FDI inflows have hovered around 1.5% of GDP between 1994 and 2002. Recent peaks came in 2005, 2006 and 2007, owing primarily to large investments in the banking sector, particularly Barclay’s USD$3.1 billion purchase of a controlling share of ABSA bank and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s USD$3.1 billion minority share purchase of Standard Bank. Vodafones’ share purchase in Vodacom (the largest mobile network), Nippon’s purchase of DiData (a large ICT company), and Walmart’s acquisition of Massmart round out some of the headline non-mining investments in recent years. Mining investments remain a vital component of FDI flows, with the likes of AngloAmerican and ArcelorMittel leading the field in this area.

The major FDI sectors have been mining, finance and retail – reflected in FDI stocks in 2009, where mining accounts for 33%, finance accounts for 27%, and other services account for 11%. The majority of stock flows from traditional European Partners, particularly the United Kingdom. However, FDI flows have been on the rise from developing Asia, particularly China and also India.

Further Resources

- Lesley Wentworth and Christopher Wood, 2014, FDI in South Africa: Promotion and Protection of Investors… and the Public Interest

- UNCTAD, 2012, Country Investment Profile (South Africa)

- Prakash Loungani and Assaf Razin, 2001, How Beneficial Is Foreign Direct Investment for Developing Countries?

- Xiaolun Sun, 2002, Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Development: What Do the States Need To Do?