The deal, valued at USD$2.4 billion, was one of the largest single inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) into South Africa, and signified that the formerly isolated country at the tip of the African continent had transformed into a gateway to the emerging ‘new growth market’ in Africa. But the Walmart deal met with mounting resistance.

Cabinet ministers joined powerful labour unions in vocal opposition to many of Walmart’s business practices, including the anticipated retrenchments of staff in the Massmart stores and the effect of the merger on competition in the retail sector. As political resistance gathered steam, government’s commitment to foreign investment was called into question. A compromise was eventually struck, in which Walmart placed a moratorium on staff retrenchments and committed to the creation of a USD$13 million fund to aid small business development – but only after months of difficult bargaining.

The Walmart case illustrates the full range on offer in South Africa’s FDI environment. It demonstrates the intrinsic desirability of investing in South Africa, with a potentially large consumer base through its reach into the African continent, and a relatively open and supportive FDI policy regime. This is possibly with the exception of its competition policy where public interest has been narrowly defined and applied by competition authorities. Also, the difficulties presented by local political and economic realities, including the presence of a well-organized and rigid labour system, and lingering doubts over the intrinsic benefits of foreign investment relative to socio-economic costs. South Africa and India share this common mix of difficult economic and political regimes, but with undeniable promise that offers up a challenging but potentially high-return environment for foreign direct investment – even as both countries prove their resilience in the wake of the global economic recession.

Economic Fundamentals

South Africa has produced solid if unspectacular growth rates over the past decade, averaging at 4% between 2001 and 2011, and estimated at 2.8% in 2013. Chronic unemployment remains a problem, with rates ranging from 26% to 41% at the high end, if discouraged labour is included. The country proved reasonably resilient to the economic crisis, emerging quickly from a short contraction in 2010, although recovery has been slower than average, hampered by weak growth in important European trading partners and persistent problems in parts of the vital mining sector.

These broad economic rates are difficult to apply to the country as a whole, which remains extremely unequal and divided, with a highly developed and competitive formal economy sitting alongside a poor and informal ‘second economy’. This inequality provides both opportunities and barriers to potential FDI. Investment in the retail and services sector is aided by the large formal sector, which provides a substantial consumer base and a large pool of skills. The strength of these retail and service sectors is complimented by the lasting importance of the mineral sector, which despite recent troubles remains well placed in a country with some of the largest mineral reserves in the world.

The situation is less promising for potential manufacturing FDI. A highly unionized and regulated workforce, combined with the inflationary drive of the formal side of the economy, make for an expensive labour force relative to developing countries in East Asia or the rest of Africa. The ability to attract low cost manufacturing investment is further complicated by relatively high corporate tax rates – which should be viewed in light of the relatively low tax base with a large proportion of the population operating outside of the formal economy. In addition, there are real concerns over technical skills shortages, as well as infrastructure and especially electrical capacity. Nevertheless, there is a concerted effort by government officials to improve the businesses environment for manufactured goods, and the industry has recently received unprecedented official attention. Much of this remains rhetoric for the time being, but certain policies have been put in place, such as the Automotive Production and Development Programme (APDP), a government-administered strategy that came into force early in 2013. When the incentive programme ends in 2020 it is anticipated that the South African automotive industry will have more than doubled domestic production from just under 540,000 to 1.2 million. These industry incentives are promising signs for would-be manufacturing investors and are potentially transformative for the domestic economy.

South Africa is also well positioned for investors seeking to enter into the African market. This status as the gateway to Africa has perhaps been overstated, particularly given the relatively weak linkages between South Africa and East and West Africa, and the continued rise of rival gateways in the likes of Nairobi or Lagos. It would then probably be truer to view South Africa as a gateway to Africa – certainly to the SADC region’s population of 280 million, where the country hosts the most developed physical, legal and financial infrastructure, and has easy access to the region via the South African Custom Union (SACU) and SADC Free Trade Area. Should the Tripartite Free Trade Area – a proposed merger of SADC, COMESA and the EAC to form a 26-country strong African free trade area – become a reality, this could bolster South Africa’s position substantially. This is especially so if as the final agreement is able to address the formal and non-tariff barriers that block broader African integration. Some of the persistent difficulties around the TFTA include rules of origin debates and harmonisation of standards; but the free trade area could provide a particularly beneficial gateway to Indian investors if progress is made on the largely stalled preferential trade agreement between SACU and India.

FDI policy

Attracting FDI has long been a cornerstone policy of post-apartheid economic policy, especially with the low domestic savings rate. The government was keenly aware of the need to rebuild the country’s image with international investors after the isolation of the apartheid era, and a concerted effort was made to build an investment environment that was liberal and open. This effort formed part of the government’s Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) Strategy, which aimed at a broad liberalization of the economy. These policy changes coincided with a wave of optimism over the unrealised prospects of Africa’s largest economy, and FDI flows initially looked positive, with investment peaking in the late 1990s with the partial-privatization of telecoms giant Telkom and Anglo American’s purchase of De Beers.

The legacy of these efforts at liberalization remains today, but South Africa is undergoing a significant transition in its approach to inward FDI. Increasing discontent over the apparently lackluster results of a liberal approach to FDI has sparked a push towards an FDI regime that gives primacy to extracting the maximum domestic benefits from each investment. The change reflects a shift in mindset: from seeing FDI as beneficial in itself, to viewing FDI as beneficial only when it achieves certain policy aims. These aims include fighting rampant unemployment, creating inclusive growth and accelerating progress – key components of the National Development Plan.

As part of this shift, the country is currently in the process of cancelling or allowing the expiration of various Bilateral Trade Agreements (BITs) accrued after the end of apartheid in the exuberant liberal phase. These BITS are set to be replaced by a single domestic investment regime that will offer various protections for investors, while allowing the country room to institute policies to redress economic inequality and meet domestic policy objectives. This is in line with in a global move towards third generation BITs.

The Promotion and Protection of Investment Bill that will make up the backbone of this domestic legislation has been stuck in a complicated parliamentary process for the past two years. Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan in his medium-term budget policy statement (23 October 2013) noted that there has been progress on the bill and associated policy framework, tax, industrial support and exchange controls.

While considered rational by many, the government’s greater focus on maximizing the domestic benefits of FDI, including implementing local and black economic empowerment partnerships, as well as local content agreements, does complicate the structuring of FDI transactions. Historically, most FDI into South Africa has come in the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&As), where the local firm is mostly equipped to comply with these requirements. Greenfields investment, which has been persistently weak into South Africa, would likely be more complicated – albeit much more desirable.

Beyond this core FDI regulation, a number of incentive schemes do exist, although generally these are less attractive than in many other developing countries. The Enterprise Investment Program (EIP) provides a cash grant of up to 30% for qualifying assets, but beyond this there are few options for large tax-holidays or lower tax rates. South Africa has experimented with Industrial Development Zones in Coega, East London, Richards Bay and Saldanha Bay (to be launched on 31 October 2013). More recently, feasibility studies have been conducted for the establishment of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in all nine of the provinces of South Africa. SEZs promise a significant corporate tax reduction and duty exclusions for those firms aimed at producing in these zones.

FDI Trends

South Africa’s FDI has been highly volatile, but trends towards levels lower than comparable developing countries despite positive changes in its investment climate since transition to democracy. Averaging 1.5% of GDP between 1994 and 2002. Recent peaks came in 2005, 2006 and 2007, owing primarily to large investments in the banking sector, particularly Barclay’s $3.1 billion purchase of a controlling share of ABSA bank and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s $3.1 billion minority share purchase of Standard Bank. Vodafones’ share purchase in Vodacom (the largest mobile network), Nippon’s purchase of DiData (a large ICT company), and Walmart’s acquisition of Massmart round out some of the headline non-mining investments in recent years. Mining investments remain a vital component of FDI flows, with the likes of AngloAmerican and ArcelorMittel leading the field in this area.

The sectoral focus illustrated by these investments – on mining, finance and retail – reflect in FDI stocks as of 2009, in which mining accounts for 33%, finance accounts for 27%, and other services account for 11%. The majority of stock flows from traditional European Partners, particularly the United Kingdom. However, FDI flows from developing Asia, particularly China, have been on the rise. Indian FDI has been on the rise, but this perhaps remains underdeveloped given the close historical ties between the two countries and their deepening partnership through BRICS.

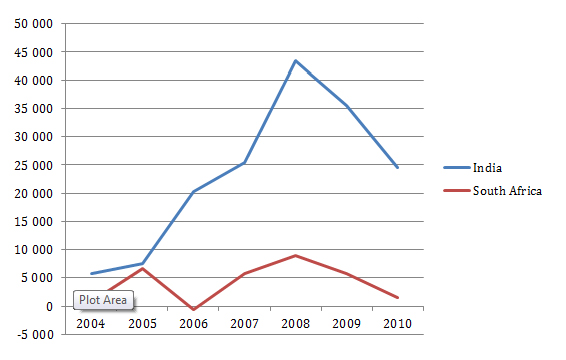

Table: FDI inflows to India and South Africa (in US$ million)

Greenfield FDI remains low sometimes expounded by the view that distortions in capital markets early on in the country’s development, through heavy reliance on mining and the government-driven monopolies in the utilities sectors. This might in part explain the continued gap between South African FDI flows and those to developing superpowers like Brazil and India. South Africa would do well to diversify and expand its manufacturing base, and there are certainly oligopolistic tendencies within the retail space which is reinforced by M&As in this sector. South African inequality actually provides scope for consumer growth – especially in a pro-poor context – on condition that economic development continues at a sufficiently high pace to bring underprivileged groups into the formal economy. These groups are extremely valuable potential customers for low-price point manufacturers, as is evidenced by the success of the likes of Tata’s 2008 investment in the economy, which at USD$1,586 billion is the largest recent greenfield project in South Africa.

Conclusion

There is a level of uncertainty particularly amongst potential investors around the future of South Africa, both in how the economy will finally be affected at the end of the economic slow-down and in how the policy environment for foreign investment will change. Considerations of FDI always involve a balancing act between this type of uncertainty and the basic economic evidence available. These basic economic variables speak to an economy with advanced infrastructure and a large nascent consumer base, strategically placed in the next major growth frontier, the African continent. The combination of these factors reflects incredible potential for growth and investment, and so long as policy can balance its development priorities, South Africa can become a unique destination for FDI.