An event co-hosted by SAIIA and the Wits School for Economics and Business Sciences (SEBS). A gloomy picture was painted of the current economic woes facing the region, the sub-title of the report Dealing with the Gathering Clouds aptly summarising its overall message.

Read the full report, South Africa is bringing down the class average – IMF Regional Economic Outlook for Sub Saharan Africa, October 2015 (188.46 kB)

The clouds include the slump in oil prices and commodity prices, high energy prices and the general weak global financial environment. Over the last two years, commodity prices have fallen significantly due to weakened global demand, particularly from a slowdown in Chinese growth.

In light of plans by the United States Federal Reserve to normalise its monetary policy by raising interest rates and reducing securities holdings, as well as the recent global reassessment of risks, external financing is also becoming more expensive. These weak external conditions are likely to persist for the foreseeable future, with oil exporters predicted to be the hardest hit.

Few of the region’s states are able to use fiscal policy to see them over the slump, as fiscal savings have been limited throughout previous periods of high growth. Due to the appreciation of the US Dollar and resultant terms of trade shocks, most currencies have come under pressure, with some states continuing to peg their currencies. Yet most states have weak reserves and are incapable of bolstering their currencies over a prolonged period. Security risks throughout the region have also exhausted budgets and hurt investment in the region.

Short-term policy recommendations include fiscal adjustment where possible and allowing currency depreciation in order to absorb the shocks. However, these changes must be coupled with longer-term efforts focused on investing in productivity-enhancing infrastructure, maintaining sustainable debt levels and removing remaining trade barriers.

A special chapter on inequality points out that even though the continent experienced fifteen years of sustained economic growth, income inequality remained largely unchanged and only a small impact on gender inequality was noticeable. However, if income and gender inequality were to be addressed and the region reached levels of inequality comparable to the ASEAN region, the IMF predicts a 1% increase in annual growth across the region.

The sub-Saharan region is vast, spanning almost the entire continent, making reports like these difficult to absorb or to take out messages for individual countries. However, picking elements from the report that directly address South Africa’s current economic and political predicament point to some useful policy lessons.

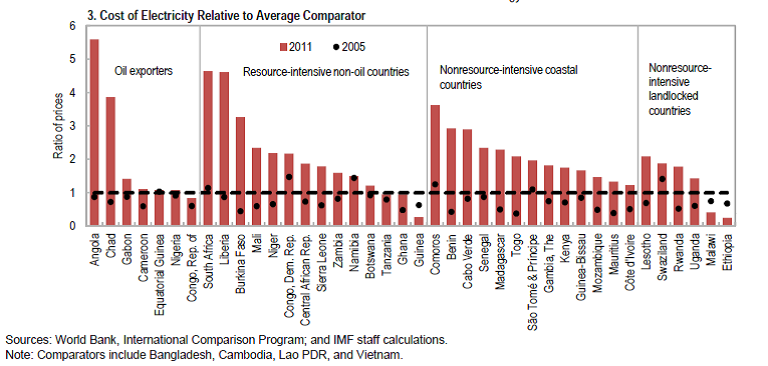

South Africa is a middle-income country alongside Kenya, Senegal, Namibia, Zambia, Seychelles, Ghana, Cape Verde, Mauritius, Lesotho, Botswana and Swaziland. Of this group, South Africa’s growth projection is the worst and worsening, from an October 2014 projection of just above 2% to now expecting it not even to reach the 2% mark. South Africa’s currency devaluation trajectory is only rivalled by the Gambia and Ghana in the region, its high electricity prices only by Liberia and Angola. Job cuts in the steel and possibly the mining sectors as well as tighter domestic policies have also contributed to South Africa’s sluggish projections for growth.

Electricity supply in the region

The lack of power generation and supply is identified as a critical contributing factor to poor growth performance in the region. It should come as no surprise that South Africa is singled out in the report, alongside Ghana, as a country that has been especially weak in upgrading its existing facilities and in investing timeously in new generation capacity. The report places South Africa on a par with Madagascar, Nigeria, Comoros and Zambia in terms of continued and consistent investment in electricity generation. See the graph below for a comparison of South Africa’s electricity costs to other countries in the region.

Commodities and Trade

All commodities, except for tea and cocoa, have seen marked declines in their prices with price projections for 2016 remaining the same or worsening. South Africa is not entirely dependent on commodities for its GDP growth or export earnings like some states in the region. The mining sector clearly remains important but has been in decline for a significant period. The global fall in coal prices should not affect South Africa too much as 72% of coal produced is consumed within the country. Equally, the limited export of coal – at 6% of total South African exports – should not have a significant impact on export earnings.

The report further makes special mention of South Africa’s general poor export performance. It notes that the ‘real effective exchange rate depreciated by about 25% during January 2011-July 2014, one of the longest and largest depreciation episodes in emerging markets.’ Yet, despite this significant depreciation, the country has been unable to capitalise via increased exports. South African export growth in this period was recorded at a low 4.3%, with its share of the world’s exports falling almost 15%. The reasons for the poor export growth clearly relate to the power supply problems with its negative effects on the manufacturing sector. However, social unrest in the form of strikes and protest also contributes to the poor performance, as well as labour market constraints including a poorly educated labour force impacting on its productivity and efficiency.

The REO calls for greater trade liberalisation and regional integration in order to cushion against fluctuating commodity prices by developing alternative markets and regional value chains. The IMF has, however, not seen significant improvements in the region’s trade competitiveness. This is an area where South Africa in general has improved significantly, bringing the costs associated with transporting goods to export destinations down. However, in regional and international fora South Africa is increasingly signalling that it is not interested in deep integration, favouring broader forums such as the Tripartite Free Trade Area above integrating into a customs union with the member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

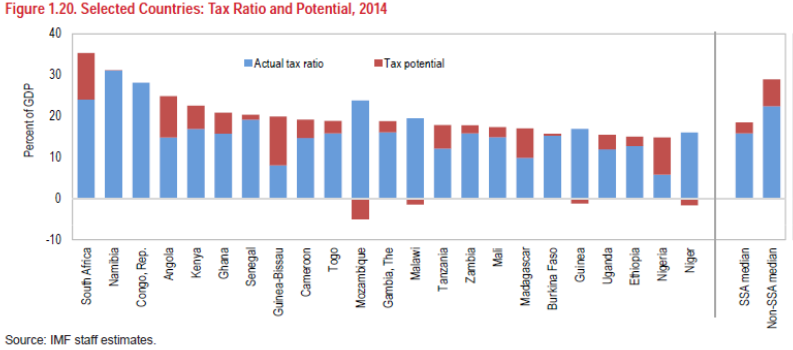

Taxation and Education

Interestingly, South Africa is identified as one of a few countries where a potential for tax increases is a possibility in order to raise more funds for government expenditure (the graph below compares the potential for increased tax revenue among countries in the region). Raising VAT is still seen as the best short-term solution for increasing taxes. This alongside better public finance management and administration capacity is the IMF’s policy recommendation for South Africa as well as Angola and Nigeria. A bigger government budget should allow for bigger and better spending in education and health, areas where South Africa is starting to lag significantly behind its peers.

Without addressing these critical factors, it is hard to see how the country’s current difficulties and social unrest can be reversed. This has never been clearer than in recent weeks in South Africa with students protesting against the high cost of education.

Interestingly the South African government capitulated very quickly to student demands, arguably due to South Africa’s past where student uprisings contributed to the fall of apartheid, but it also points to a weak government that has not engaged in depth with its own policy orientation and fundamentals, its medium and longer-term economic development plans or their implementation. Reactive policy decision-making holds clear dangers for the stability of the country.

Whereas the findings of the REO report were neither new nor surprising, governments would do well to take heed of the warnings contained therein and start to think deeply on how the gathering clouds can be cleared away in the medium to long term by implementing some of the IMF’s policy recommendations, including maintaining debt sustainability and allowing the currency depreciation to run its course.