On a panel the next morning, chamber CEO Roger Baxter remarked that there was an ‘unpalatable item on the menu’ in the form of Mineral Resources Minister Mosebenzi Zwane. Indaba chairman Bernard Swanepoel persistently referenced the chamber’s absence. Through a digital vote, most delegates (presumably not represented by the chamber) opined that it was wrong to boycott the dinner. Zwane took the opportunity to say that he was open to talks about the charter. But the chamber argued that the ‘horse had bolted’. When talks were necessary, Zwane had refused to include industry voices.

With its input almost completely ignored in the third iteration of charter, the chamber approached the courts to have it set aside. During the indaba, the chamber emphasised that it would engage with the minister through the courts unless significant steps were taken to restore trust.

At the indaba, Sipho Pityana, convener of the Save SA campaign, called the minister a ‘crook and a comedian’. While the majority of delegates indicated (again by digital voting) a belief that dialogue was the only hope for a battered industry, they appeared willing to overlook the moral hazard of Zwane’s alleged lack of integrity.

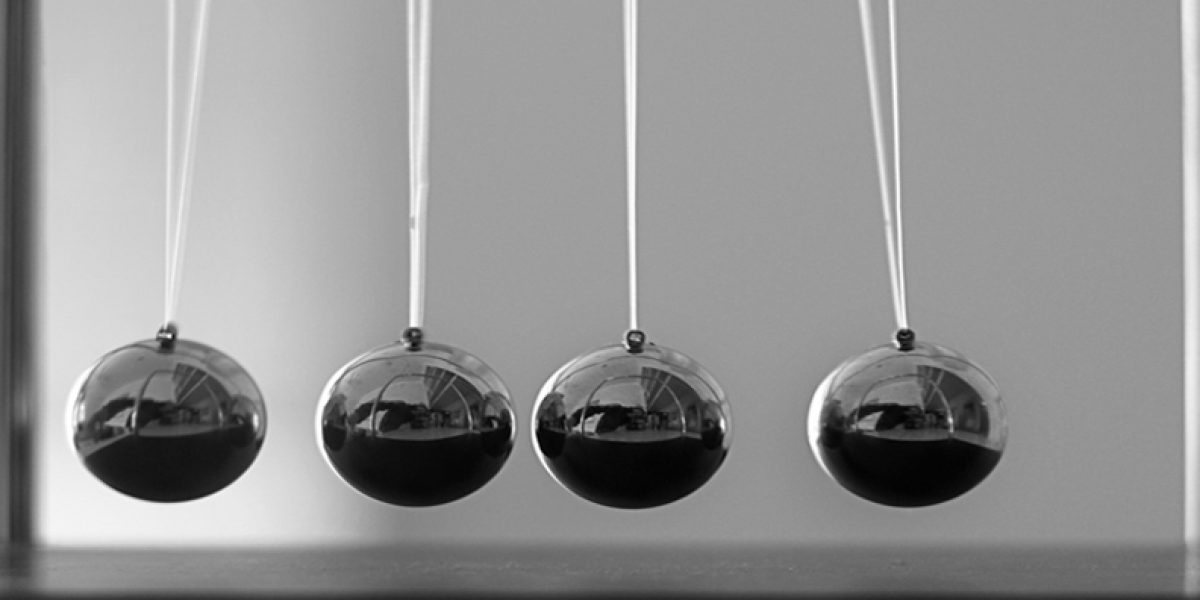

Analytically, the row is best understood as a prolonged game of tit-for-tat between the state and the industry. Tit-for-tat is a potential solution to the prisoner’s dilemma, a game in which two sets of players are rationally bound to a dominant strategy that results in the mutually worst outcome for each of them. Playing tit-for-tat means co-operating with your rival if he or she co-operated during the most recent play of the game. If punishment occurs, it lasts only while your rival cheats. Repeated punishment cycles can, however, occur due to information asymmetry and mistrust between the players.

In August, Zwane invited representations on his proposal to restrict the receipt of or grant of any new application or renewal for a prospecting or mining right, tantamount to a blanket freeze on any new business in the mining sector. The move was a response to the chamber’s application for a court interdict to stop the implementation of the new charter, which was gazetted on June 15. About R50bn in mining stock value disappeared from the JSE after the charter was gazetted.

Surprisingly, Zwane’s freeze proposal came shortly after he had agreed to suspend the new charter’s implementation until the court had made its ruling. To counter the freeze, the chamber launched an urgent application with the High Court in Pretoria to set it aside. The minister subsequently withdrew the notice.

Since 1994, the chamber and the government have mostly managed to maintain a co-operative equilibrium. But after Zwane was parachuted in to replace Ngoako Ramatlhodi in the portfolio, it has become dysfunctional. The chamber has increasingly resorted to the courts, departing from its previous method of backdoor talks. This is now the chamber’s primary punishment strategy.

Zwane’s counter punishment strategy is to gazette notices that create confusion for existing and prospective mining interests. When either player perceives the other to have defected from the co-operative space, they punish their rival. In an infinitely played game, it is only worth defecting if the net present value of that defection outweighs future gains.

Why would the minister pursue this destructive defection strategy, one that jeopardises a major tax rent stream? One answer is that tit-for-tat is being played within a broader kleptocracy game, in which the ruling coalition accesses mineral rents and distributes them to loyal clients. This coalition may well calculate that the net present value of defection — for the sake of benefiting politically connected insiders in the short run — is worth the risk of jeopardising the industry in the long run.

Prevailing analyses of SA’s political economy assume that the country is relatively strongly institutionalised. The Constitutional Court regularly rules against the executive, and the media do an excellent watchman job. Until recently, the public protector was unafraid to speak truth to power. However, crucial institutions have been captured by the governing coalition. National Prosecuting Authority head Shaun Abrahams has avoided acting against the president but has shown his willingness to act against the president’s enemies. This includes action against former finance minister Pravin Gordhan on the grounds of a KPMG report that the company itself now admits was highly problematic. Even when the Constitutional Court rules against the president, the institutions designed to hold him to account flounder. The sheer extent of state capture as revealed in the recent Gupta e-mail leaks has demonstrated that SA is better described as a weakly institutionalised state.

Economists Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Thierry Verdier write that ‘kleptocracy emerges in weakly institutionalised polities, where formal institutions neither place significant restrictions on politicians’ actions nor make them accountable to citizens … the absence of strong institutions allows rulers to adopt political strategies which are highly effective at defusing any opposition to their regime’.

Kleptocrats maintain power while pursuing policies that are self-enriching but costly to society. The logic of the strategy is to allow the ruler to bribe politically pivotal groups to avoid challenges to his rule. It exploits the fragility of social co-operation in already divided contexts to make it difficult for citizens to overcome the difficulties of uniting against the ruler. Typically, the kleptocrat uses rents from natural resources both for his own consumption and to bribe potential opponents.

Zwane is a pivotal player in this game. In an affidavit filed by the Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse, the chief operating officer, Benjamin Theron, asserts that the leaked Gupta e-mails show ‘evidence of conduct that constitutes crimes of extortion, fraud, theft, corruption and high treason on the part of Mosebenzi Joseph Zwane… This misconduct occurred during Zwane’s tenure as minister of mineral resources as well as his tenure as MEC for agriculture and rural development in the Free State province.’

Among other things, the affidavit explains how Zwane reportedly used his public office to facilitate the sale of Optimum Coal Holdings assets from Glencore to Tegeta, a company owned by the Guptas. This sale was followed by the conclusion of coal supply contracts between Tegeta and Eskom at inflated prices.

It further alleges that Zwane ordered the release of Koornfontein Mine’s R280m rehabilitation trust fund and Optimum’s R1.47bn into the Guptas’ Bank of Baroda accounts ‘without ensuring that these funds were properly ring-fenced and secure and would be utilised for their proper purpose’. This appears to constitute evidence of using political power to channel rents into the hands of politically connected interests for personal enrichment.

It is all enabled by the president, who appoints cabinet ministers to serve at his pleasure or allows the Guptas to appoint them, as they allegedly did with Zwane. It bypasses the rule of law and suggests that Zwane’s latest move is a means of crippling current interests in the mining industry to make assets cheaply available to be stripped by Gupta-connected companies. At best, it creates confusion.

While we should celebrate that the judiciary functions well and that the media diligently expose wrongdoing, citizens should not become complacent. Kleptocrats are notorious for enduring longer than expected. They manipulate political institutions such as the Mining Charter to channel rents via economic institutions including Tegeta, Trillian and Eskom. McKinsey and KPMG appear to have been willingly complicit. These rents are used for personal consumption and are distributed among key members of the governing faction to consolidate power.

Is there a way out of the unco-operative equilibrium? The game theoretic analysis strongly suggests that co-operation cannot be re-established under current conditions of mistrust between the players. This creates an impasse that raises investors’ political risk significantly. The minister’s invitation to dialogue was disingenuous. At best, it was too little, too late and it included an explicit instruction that the industry should not tell him how to make mining laws.

Can the industry bypass these kleptocratic distortions? Possibly, but ultimately there is no substitute for strong governance to create a thriving industry. The minister himself constitutes the single biggest obstacle to making SA an attractive investment jurisdiction. As Hulme Scholes, a veteran lawyer in the industry, put it at the indaba: ‘The minister must go; he has no understanding and no will to make the industry work properly.’

Once the kleptocratic elements are removed, a co-operative equilibrium can be restored in the tit-for-tat game. Subsequent growth and transformation could move us out of this game entirely.