South Africa’s 2019 general elections will be a critical moment for democracy as the country welcomes a post-Zuma future. Equally important is the impact of his presidency on South Africa’s international standing. This piece will reflect on South Africa’s foreign policy under President Zuma – exploring the direction and key achievements and shortcomings/failures during his tenure. To what extent has South Africa’s foreign policy in the Zuma administration responded to domestic and continental needs?

Historically, the Mandela administration reintegrated post-apartheid South Africa into the global community, while restoring a positive image of South Africa in institutions like the United Nations (UN) and the South African Development Community (SADC). Nelson Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, focused primarily on Africa’s development with his ‘African Renaissance’ philosophy that emphasised ‘African Solutions to African Problems’ and encouraged African Unity. He was the founding father of key African institutions and frameworks like the African Union, the Pan-African Parliament (PAP), New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM).

Under Zuma’s presidency perhaps the most notable achievements were South Africa joining the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) grouping in 2011, as well as strengthening South Africa’s relationship with China and continued the call for a more representative and equitable governance structure in global multilateral institutions like the World Trade Organisation and United Nations Security Council (UNSC). On the domestic front though, the Zuma administration has flagrantly contradicted SA’s commitment to human rights and Ubuntu, enshrined in the Constitution and embodied in Mandela’s leadership’.

Human Rights

Events like the Marikana Massacre in August 2012, where police opened fire on striking mineworkers in South Africa’s platinum mining belt, have demonstrated a dangerous slippage in South Africa’s commitment to human rights.

South Africa has seen a 96% increase in protests since 2010, including service delivery protests, according to the Institute of Race Relations. Given the history of police brutality during the apartheid era, the August 2012 killing of 34 Marikana mineworkers by police remains a permanent stain on the country’s human rights record.

The ICC

South Africa decided to withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC) following widespread condemnation of the government’s failure to detain Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir when he visited the country for the 2015 AU-Summit. Bashir has evaded the ICC indictment since 2009 and is wanted on charges of genocide and war crimes. The attempt to withdraw has marred international perceptions of South Africa as a protector of human rights.

In February 2017, the Pretoria high court blocked the withdrawal, stating it was unconstitutional and invalid without prior parliamentary approval. Justice Minister Michael Masutha has said that the government is determined to pursue withdrawal and in December 2017, tabled a bill that seeks to repeal the Implementation of the Rome Statute Act and withdraw South Africa from the ICC.

In defending its decision to withdraw, the South African government argues that the ICC is an instrument used unfairly against African countries and fails to hold western powers (some of which like the US, are not ICC members) to the same standards. A similar argument was made by Burundi, which withdrew from the ICC last October.

As is stands, institutions like the African Union have demonstrated limitations in holding leaders who have committed crimes against humanity to account. While the African Court of Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) already exists, it is unlikely to be an effective alternative to the ICC considering that the 2014 Malabo Declaration statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights has not been ratified by member states.

Africa engagement

South Africa’s role in Africa has been significant on many fronts including peacekeeping operations and trade. It has one of the biggest economies on the continent with a gross domestic product (GDP) valued at $301 billion in 2016, with advanced infrastructure. Post-apartheid South Africa has been a promoter and champion of peace and development on the continent, having facilitated and/or mediated political negotiations in SADC (Lesotho, Madagascar and Zimbabwe). The country has also been active in Francophone Africa after President Mbeki facilitated talks in Côte d’Ivoire in ethnic-motivated conflicts in 2006.

The country has been engaged in various peacekeeping operations in several African countries including Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Sudan. South Africa has deployed troops as part of the United Nations peacekeeping force in eastern DRC since 1999 when the second Congo war broke out. This was extended last April 2017 to March 2018. South Africa also took over as commander of the UN Force Intervention Brigade in January 2015, an extension of the UN Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) mandated by the United Nations Security Council and acting on recommendations of former UN Secretary General Bank Ki-Moon.

While South Africa has been involved in UN peacekeeping operations under the Zuma-led government, there has been less involvement in strengthening key institutions and instruments like the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG) – a treaty created in the AU to encourage better governance in Africa which coincides to a large extent with South Africa’s developmental aspirations for the continent. Mbeki’s engagement in the region was more holistic.

Xenophobia

The South African APRM Country Review Report in 2007 forewarned the rise of xenophobia due to growing hostility towards foreign nationals by locals. In 2008, violent attacks broke out resulting in the deaths of more than 60 foreign nationals. There was more violence in 2015 which President Zuma condemned and appealed to South Africans not to blame criminal acts on foreign nationals.

There have been numerous related incidents since, including an anti-foreigners march in Pretoria in February 2017. In a televised speech in response to the anti-foreigner’s march, Zuma remarked: “The march in Pretoria today, which was also attended by foreign nationals, was anti-crime not anti-foreigners and we appeal to all the marchers to protest within the confines of the law.”

Both Presidents Mbeki and Zuma have denied that such acts can be labelled as xenophobic on the basis that South Africa hosts more immigrants than Europe, and African countries were so hospitable to exiles from South Africa historically.

This flagrant denial of a concerning phenomenon further strains South Africa’s relationship with the rest of the continent, particularly with countries like Nigeria which recalled its ambassador after the 2015 attacks. Although South Africa’s relationship with Nigeria has often been rocky, xenophobic incidents have further diminished South Africa’s position as a continental leader.

Stronger ties with China

This year marks 20 years of diplomatic relations between South Africa and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Apartheid South Africa had strong ties with Taiwan before the ANC switched allegiance to the PRC in 1998. Although ties with Beijing under Mbeki appeared to be somewhat superficial, with continental development taking priority, a key development included the formulation of a bi-national Commission in December 2001 and the elevation of ties in the second bi-national commission in June 2004 to a Strategic Partnership which saw South Africa granting market economy status to China. This entails the lowering of anti-dumping duties and/or imposing quantitative restrictions to protect domestic industries.

It was no secret that Mbeki had some reservations about China’s trade interests, warning Africa to ensure China’s engagements are not merely a different form of colonialism of Africa.

China was not a high priority for the Mbeki administration. Mbeki took longer than Zuma to advance relations with China; the formulation of a Bi-National Commission and signing of a Strategic Partnership took place two years after he assumed power in May 1999. However, South Africa’s engagement with China strengthened with an announcement of upgrading relations to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) on Zuma’s first state visit there in 2010 having assumed power in 2009.

While economic and political relations continue to deepen with China, there is a relative decline in diplomatic and trade relations with the West, particularly with the United States of America (USA). Tensions between SA and the US arose in 2015 when then US President Barack Obama threatened to rescind South Africa’s duty-free access for certain exports to US markets under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). This occurred following South Africa’s imposition of anti-dumping duties against US chicken to protect domestic markets. Between 2012 and 2013, US chicken exports declined by 33 percent because of the market barriers imposed by South Africa. Ultimately, South Africa made a compromise to keep AGOA benefits and allow some concessions of US meat into its markets. AGOA expires in 2025 and there are three options that remain: to do nothing and revert to WTO regulations, a partial trade agreement or full trade agreement. There has been no indication what will happen post 2025.

Africa has appeared to be a low priority for the Donald Trump administration, with his agenda primarily looking inward to put America First. He hosted nine African countries during the 2017 United Nations General Assembly for a luncheon, calling for Africa to invest in the United States and help defeat terrorism.

More than a year into Trump’s presidency, several senior positions remain vacant including the US ambassador to South Africa. This indicates deteriorating relations between the two nations.

Meanwhile, China has emerged as a key player with the second largest economy and driver of a global agenda, while the US’s power recedes. From this perspective, South Africa’s partnership with China is beneficial for the coordination of common interests which include advancing of national interests, South-South cooperation and the AU Agenda 2063 which is a strategic framework for the continent’s socio-economic transformation. However, there are concerns that South Africa has not done enough to maintain strategic partnerships with countries other than China, while China continues to maintain strategic relations with its ‘rivals’ (United States of America) and other key actors such as the EU for commercial purposes.

China has become South Africa’s biggest trade partner during Zuma’s presidency, mainly importing raw materials from South Africa and exporting manufactured goods. Statistics from the South African Revenue Service (SARS) show that by October 2017, South Africa had a trade deficit of 9.2% with China compared with 5.1 % with Germany – an EU member and second largest trade partner to South Africa. This trade imbalance and quality of trade relationship goes against the ideals of win-win cooperation. This calls for more robust and strategic measures in the nation’s foreign policy trajectory to respond to domestic needs by promoting trade with other regions.

Admission to BRICS

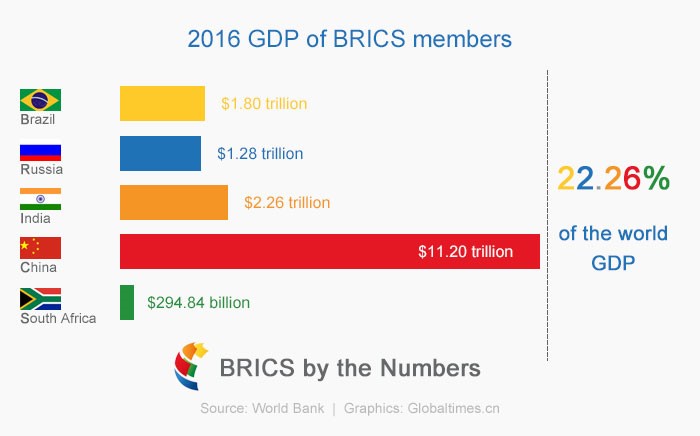

The admission of South Africa into the BRICS grouping of emerging markets was a crowning achievement for the Zuma administration in 2011, allowing the nation to potentially advance its national interests, develop infrastructure and promote regional integration, as well as give substance to its interests in South-South cooperation. However, this membership drew criticism and cynicism by media and economists due to South Africa’s relatively small economy and slow economic growth when compared to its ‘new friends’.

It is South Africa’s friendship with China, elevated under Zuma, which proved advantageous and valuable considering that Nigeria – Africa’s largest economy, also had an interest in joining the group, remarked the outgoing chairman of the Manufactures Association of Nigeria, Mr. John Aluya.

“Consistent with the spirit of inclusivity, any partnership with Africa must benefit the whole Continent and encompass a holistic approach,” Zuma remarked at an informal meeting of BRICS leaders on the margins of the Group of 20 (G20) in July 2017. South Africa drove the call for a BRICS bank to finance infrastructure development across the continent at the eThekwini Summit in 2013. In line with the summit declaration, The New Development Bank (NDB) was launched in July 2014 in Shanghai. Last year Zuma launched the African Regional Centre (ARC), with the purpose of financing sustainable infrastructure development projects, particularly in South Africa and in the region.

In a first, South Africa invited the chairs of African Regional Economic Communities (RECs) to attend the 2013 eThekwini Summit as observers and allowed them side-line meetings with BRICS heads of state. This practice has been adopted in subsequent BRICS summits.

“With so many big powers in the BRICS, South Africa’s role has become that of a mediator and influencer in disagreements and adoption of summit resolutions,” remarked a DIRCO official at a BRICS dialogue in Pretoria in October 2017. This further underscores South Africa’s relevance and position within the grouping.

Similarly to the BRICS, South Africa’s role as the only African state in the G20 is catalysing the African Agenda. Zuma said in a statement after the G20 Hamburg Summit in July 2017: “Despite disagreements on certain issues, the Summit managed to discuss and agree on various developmental matters that would be of advantage to South Africa and the African continent including the launch of the G20 Africa Partnership. The partnership will include developmental projects such as G20 Initiative for Rural Youth Employment in developing countries with a focus on Africa”

Zuma is dogged by numerous scandals which have impacted on South Africa’s global image and financial reputation.

From a regional perspective, South Africa, with Zuma at the helm, evolved from being a strategic and intellectual founder of key influential institutions on the continent to a multilateral actor with vested interest in aligning with emerging powers. Whereas the African agenda was a priority for Mbeki, Zuma tended to advance Africa’s interests through multilateral platforms like the G20, BRICS and FOCAC. He called for the reform of existing global financing institutions as well as infrastructure development, notwithstanding the criticism by other African states that South Africa was furthering its own interests. Zuma’s legacy will also be associated with achievements in BRICS, the ARC and deepened relations with China. South Africa admittance to BRICS has been beneficial in placing South Africa at the table in discussions that shape the global agenda.

For South Africa to successfully further its foreign policy objectives in the Cyril Ramaphosa era (assuming the high probability that the ANC will win the 2019 national elections), the incoming administration needs to incorporate numerous changes in its approach.

Firstly, as a basis for the promotion of the nation’s position and image, the administration needs to clearly define norms and values, such as human rights, that are central pillars in its foreign policy. Secondly, in the vision to bring about continental development, there is a need to strengthen African institutions like the AU through financing and implementation of measures set out in ACDEG to improve the state of governance in the continent and for South Africa to regain global confidence. Finally, adopting a more pragmatic approach and diversifying relations with other global actors other than China for commercial purposes and to respond to domestic needs.