The Agenda was envisaged in 2013 to provide a vision and strategic framework for achieving African development over the next 50 years. The 24th Summit resolved to adopt a 10-year plan by the next meeting of the AU in mid-2015 that incorporates the 2063 vision with a concrete plan of action.

This plan is to be the product of widely-held consultative processes which have already started and will continue until the June 2015 meeting of AU Policy Organs. The challenge for the AU in going forward from the 24th Summit is, therefore, to transform Agenda 2063 from a vision to a concrete action plan.

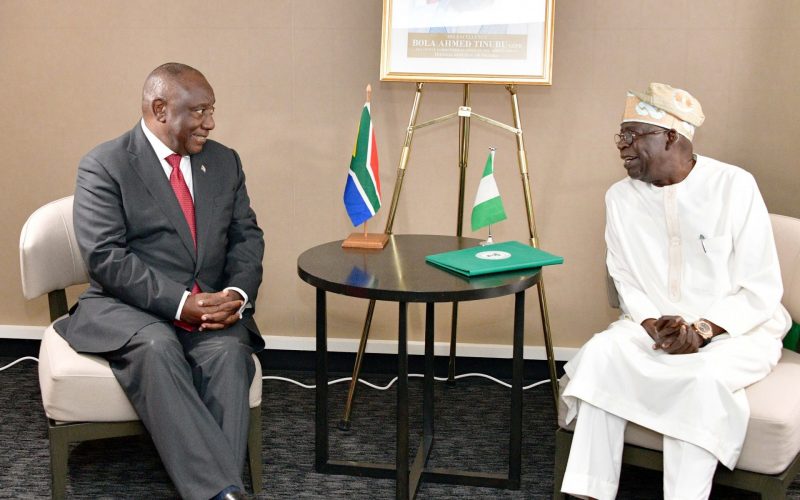

Chairperson of the AU Commission, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, opened the Summit raising the concern that Africa’s development is balanced on a knife edge. Emerging from a past of mediocre performance, the continent’s future development path is at a crossroads. It could yield more mixed results if a lack of continental co-ordination and the pursuit of national interests undermine regional integration.

Or, renewed political will towards regional commitments and the ability to follow through on them could realise the unified and prosperous continent of which pan-Africanists dream.

Agenda 2063 attempts to create a unified growth agenda for Africa which is only possible if African countries can successfully collaborate.

Trade and investment are two key examples of this type of collaboration which has occurred so far, and are crucial to any continent’s development. As such, a focus on trade and investment integration must be at the centre of Agenda 2063.

Africa has ambitious plans to integrate the continent – chief among them the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) that aims to connect the Southern African Development Community, the East African Community, and the Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa, creating a free trade area that spans 26 countries from the Cape to Cairo.

Furthermore, the recent Summit resolved to introduce a single African air transport market for all African airlines by 2017. While Africa has no shortage of grand ideas and regional commitments, it is plagued by a perennial problem of a lack of follow through. Reaping the gains from these initiatives will require a focus on some basic fundamentals which Africa is not currently getting right.

Despite the High Level African Trade Committee at the Summit resolving to increase trade liberalisation, the complex web of regional trade agreements have done little to facilitate intra-regional trade which remains around 12%, compared to approximately 40% in North America and 70% in Europe.

This is primarily due to the presence of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) which serve to ‘thicken’ borders in Africa, despite the dismantling of tariff barriers. Ranging from costly and burdensome customs procedures, onerous health and safety standards, to blatant bribery and corruption, NTBs make cross-border business more difficult and transport costs much higher, further undermining Africa’s global competitiveness.

See the SAIIA study this article draws from on our specialised trade website, ‘Regional Business Barriers: Unlocking Economic Potential in Southern Africa‘.

Efforts to shift focus from tariff liberalisation to NTBs is well underway, but commitment from African policy-makers and bureaucrats to the goals of trade facilitation is weak. For instance, in view of the TFTA, each of the three regional economic communities have established an NTB monitoring mechanism allowing businesses to register the NTBs they experience. However, once registered, NTBs sit on the system for up to three years without resolution. The system has failed since state and private sector actors disagree on the nature and necessity of the NTBs, and there is no arbitration or resolution mechanism available.

It is becoming clear that the sector best suited to driving regional integration and the removal of NTBs is the private sector. This sector has a direct incentive to facilitate cross-border trade, nuanced on-the-ground experience in conducting business in Africa, and is the provider and recipient of FDI. As such, the private sector – more than the state -needs to meaningfully champion regional integration and NTB elimination in Africa.

It is essential that governments and regional bodies engage with the private sector when making and implementing regional integration policies. Regional business organisations need to be strengthened, or developed where they do not exist, to distil a unified private sector voice across the African continent.

Aside from healthy trade relations, the continent also requires major investment in upgrading productive capacity to ensure sustainable development. In a continent with severe skill and knowledge shortages, foreign direct investment (FDI) is a crucial contributor to the diffusion of technology and knowledge. FDI facilitates the expansion of many of the fundamentals of growth such as information and communication technology and public infrastructure.

A related article, ‘Regional Integration in Africa: Can Agenda 2063 be different?’

Despite its high levels of growth and relatively untapped markets, Africa suffers from the perception of poor investor climates. Political stability, sound governance institutions, and domestic policy in line with international investment law are all basic determinants of FDI attractiveness. The need to improve investor attractiveness is evert more urgent given fierce competition from emerging Asia and resurgent America.

There is much that can be done to improve African countries as investment destinations. The harmonisation of investment regulation is a first step to encouraging FDI to flow across borders, making regional blocs a more appealing investment market, and contributing to market integration.

However, investment policy should also recognise the importance of domestic policy space for sustainable economic development. Recent controversy has been sparked by South Africa cancelling its bilateral investment treaties and introducing draft legislation which is viewed as reducing investor protection. Part of the regional harmonisation challenge will be deciding how to balance investor rights with government’s regulatory discretion, as well as considering factors such as indigenisation and local content requirements. In addition, African countries should undertake focused and co-ordinated investment promotion strategies which ensure that FDI is attracted and directed to the right locations on the continent.

Agenda 2063 is a long-term objective spanning 50 years into the future.

African countries suffer from the tendency to make regional commitments and then abandon them when it comes to implementation. A key question is, therefore, whether African leaders will have the political will to carry through the commitments they have made in Agenda 2063. If not, the private sector will have to carry the torch of regional integration into the future.