We can’t wait through years of debate about modalities and points of reference. We can’t wait while strong countries coddle the weak and ruined with warm and fuzzy notions of equality. Timidity bears too high a cost.

The time for Africa to catch up with the rest of the world is now, and if we fail to do so, the time may not come again.

Getinent Giorgis, a director of the African Development Bank, says sustainable development and poverty alleviation require that Africa’s collective economy grows by at least 8% a year. We’re missing the mark. The continent grew at only 3.5% from 1995 to 2002.

Africa’s problem isn’t lack of capital. If we’re going to realise the vision embodied in the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad), the private sector must be fully embraced as an equal partner with government.

There are more than a billion Africans in the world – 800 million on the continent, 300 million in the diaspora. If brought together to form a ‘virtual global African economic community’, they would create a market worth $1 trillion and consuming $500 billion in goods and services. That was the conclusion reached by delegates at the Global African Business Titans Conference held in Johannesburg in 2003.

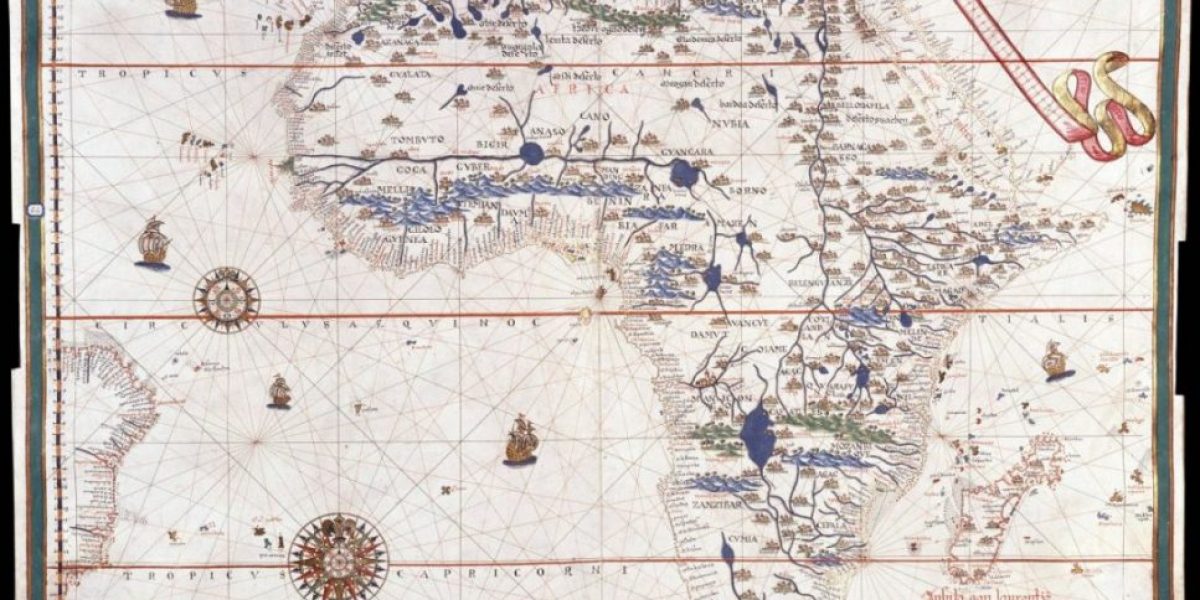

The key is stability and political courage. The main population centres – Nigeria in the West, Kenya and Ethiopia in the East, Algeria and Egypt in the north, South Africa at the tip and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the middle – are also the continent’s economic engines. These countries must set the pace.

Indeed, Africa needs its own G8. We all remember how ineffective the principle of non-interference made the Organisation of African Unity. Huge power disparities exist between, say, South Africa and Lesotho, Nigeria and Liberia, Kenya and Cameroon. The strong mustn’t run roughshod over the weak, but through the auspices of the African Union and Nepad, they must lead by example.

It can be argued that the continent’s stronger nations have won this right to set the agenda. They are the dumping grounds for Africa’s poor. Theirs are the streets teeming with beggars from the rest of the continent where dysfunctional economies lock millions in misery. Had Mugabe and his cronies not turned a prosperous nation into a basket case, Zimbabwe’s blind and needy would not be castaways on the traffic islands of Johannesburg with tattered cardboard signs and soiled rags.

No country has prospered by importing poverty or draining its limited resources to build houses and provide jobs for the entire continent. Africa’s club of leading nations needs to firmly insist on good governance, respect for the rule of law and an end to corruption.

They should waste no time aligning their economies. They should create an environment conducive to doing business and attracting foreign direct investment. They should encourage a culture of entrepreneurship and facilitate the movement of human capital between their countries.

This, in turn, would lead to the emergence of a large and vibrant private sector, ultimately making people less dependent on government largesse. It would allow a strong civil society to evolve.

But all this will be impossible without stability on the continent and good governance. Business can be excused for having jitters over the apparent lack of enthusiasm to ratify the protocols of the African Peer Review Mechanism. Hesitation by governments on this fundamental programme sends a message that Africa’s leaders like the idea of collective scrutiny far less in practice than in theory.

But having raised the standard by adopting peer review, Africa must now follow through. Whether we like it or not, we have given foreign donors and investors a new yardstick by which to measure us. At some point, some country is going to have to fail the review.

Africa stands at a crossroads. We either make a clean break from the past or lose the renaissance. If the strongest set the standard, we can become prosperous. If they waffle, the world will leave us behind.