The return of liberal democracy

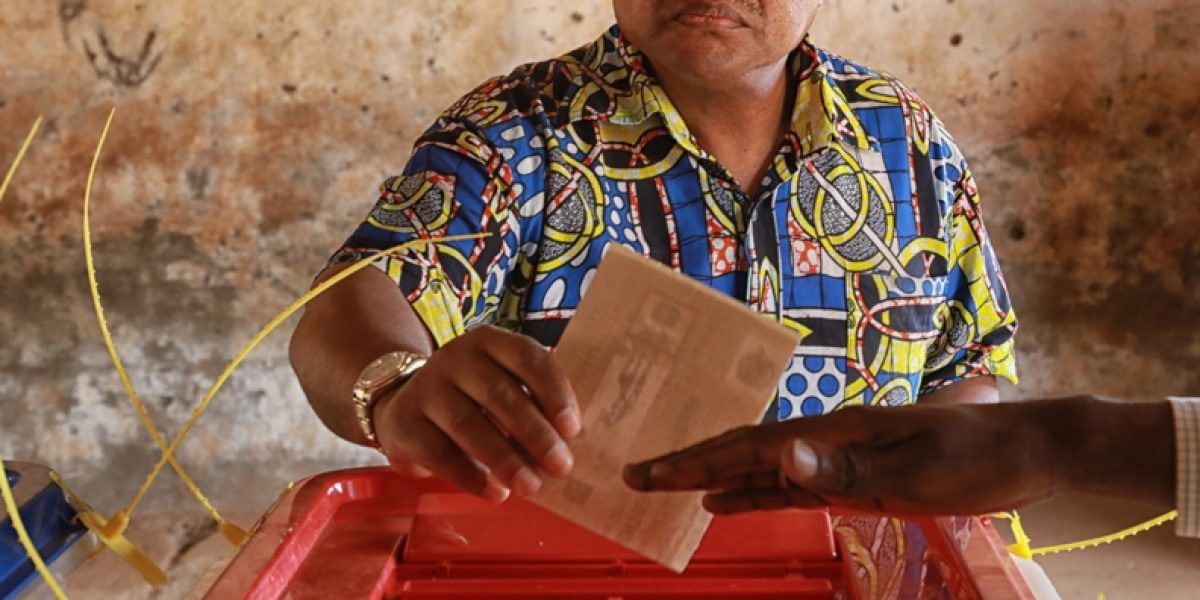

After the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the perceived triumph of liberal democracy, coupled with cajolement from the victorious Western donor governments led many African states to re-introduce multi-party political systems, after decades of one-party or military rule. Competitive elections became institutionalised. Africa developed standards outlawing unconstitutional changes of government.

Democracy, it seemed, was making its biggest comeback since the crumbling of colonialism from the 1960s onwards.

Today, almost all African states stage multi-party elections every four or five years. Fifteen polls have been planned for 2016. The first half of the year saw elections in Benin, the Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Niger and Uganda, with elections also slated for the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, the Gambia, Ghana, São Tomé and Príncipe, South Africa and Zambia.

But have constitutions, electoral processes and term limits been respected, or have incumbents tried to keep the keys to State House by all means necessary?

January-June: Delays, reruns and boycotts

While there has been improvement from deplorable polls in the past, unfortunately many African elections are still delayed because of coups d’état and other unconstitutional changes of government, undoing constitutional term limits and consequent violence. When the ballots do proceed, they are often marred by vote-rigging, opposition boycotts, logistical problems and court challenges.

The Central African Republic, engulfed by instability and violence in recent years, saw a chaotic and contentious electoral process. A coup d’état in 2013 ousted President François Bozizé, which led to an internecine conflict with religious dimensions, pitting Muslims against Christians; a series of interim administrations; and suspension from the African Union (AU). The constitutional court reinstated the right of refugees to vote (a million people of the country’s 4.7 million are estimated to have fled violence). Parliamentary and presidential elections were originally scheduled for October 2015, but they were postponed to December after violence in the capital Bangui. A successful legal challenge annulled the parliamentary results and forced a rerun in February 2016, together with a second round of presidential elections in March. With 63% of the vote, Faustin Archange Touadéra, a former Bozizé-regime prime minister, was elected president. The courts rejected further petitions for annulment, and the main opposition leader Anicet Georges Dologuele, accepted the result ‘for the sake of peace’ (despite having won 24% of the vote to Touadéra’s 19% in the first round). The AU then lifted the CAR’s suspension.

In Niger in 2011, the army ousted President Mamadou Tandja after mass protests when he failed to change the constitution to allow himself a third term bid. Interim military leaders kept their promise to hold early elections, won by Mahamadou Issoufou. In February 2016, presidential and legislative elections saw Issoufou romp home with 92% of the vote. A 20-party coalition called a boycott and threats of terror attacks saw a low turnout. Opposition leader Hama Amadou was arrested for alleged child trafficking shortly after announcing his candidacy. Voters lacked proper identity documents and voting stations ran out of materials, extending the poll for a day.

Term limits were dropped from Uganda’s constitution in 2005. As expected, February elections saw President Yoweri Museveni comfortably notch up his seventh five-year term since 1986. His perennial rival, Dr Kizza Besigye, was repeatedly arrested before and after the vote (as in previous campaigns). Opposition rallies were broken up and social media platforms were shut down, raising tensions. Like all Uganda’s elections since 2001, allegations of ballot rigging and voter intimidation were insufficient to overturn the result.

Chad dropped term limits in 2004, and President Idriss Déby won his fifth mandate (since his 1990 coup) in the April elections. A splintered opposition fielded 13 candidates. With consummate chutzpah, Déby promised to reinstate two-term limits if re-elected. The opposition is making noises to reject these results amid electoral boycotts and intimidation.

Similarly, in the Republic of Congo, incumbent Denis Sassou Nguesso, at the helm for 32 years, garnered 67% of the vote in March. An October 2015 referendum, (dubbed a ‘constitutional coup’ by opposition parties), removed both term and age limits, paving the way for his umpteenth run. The European Union refused to send observers. Calls to delay the polls due to disorganisation by the new electoral commission were ignored. On polling day, the country was in virtual lockdown: car use was banned, businesses stayed shut, and police and soldiers menacingly patrolled the streets. Cellphones were blocked during and after the elections, increasing anxiety around the results. At least 18 people died in protests, and opposition forces alleged massive rigging, to no avail.

Djibouti changed its constitution in 2010 to jettison term limits. President Omar Guelleh won his fourth term handsomely (breaking a promise not to run), with 87% of the vote in April, despite a boycott by major opposition parties. Perhaps the fact that the US, France and China have large military bases in Djibouti explains their silence.

In the troubled archipelago of Comoros – which has faced over 20 actual or attempted coups since independence in 1975 – inconclusive February polls necessitated a second round in April. The unusual electoral system chooses the president on a rotational basis from one of the three major islands. Colonel Azali Assoumani (twice a former president) narrowly emerged victorious. Courts dismissed accusations that the electoral commission falsified results, despite public protests.

Observers gave the thumbs up to the election of businessman Patrice Talon in the second round of Benin’s election, with a peaceful transition from the regime of President Thomas Yaya Boni (rumoured to have eyed an unconstitutional third term, although never publicly pronounced).

Looking forward: mixed prospects

Will the rest of 2016 change this mostly depressing picture?

There are rosy re-election prospects for long-time incumbents in Equatorial Guinea, São Tomé and Príncipe and the Gambia, with space for civil society, opposition parties and media severely restricted. More than 30 people died in the Democratic Republic of Congo protesting against a new electoral law. Anxiety is high over the likelihood that the 2016 elections could be delayed for several years due to alleged unpreparedness, lack of funds and a census, and a compromised voters’ roll. Is this a stratagem to extend the constitutionally-curtailed reign of President Joseph Kabila?

But democratic stalwarts present some hope. Local elections in South Africa in August (despite scandals swirling around the ruling party) and presidential polls in Ghana in December (despite concerns over the integrity of the voters’ roll) are both widely expected to be well run, free and fair and peaceful. Zambia faces its fifth leader since 2008, after the death in office of two presidents, with a tight but calm contest predicted.

What can we learn from 2016?

On 19 April, Koffi Annan urged African leaders to leave office when their time is up, or risk coups and uprisings. Threats of violence lead African observer missions to value peace above all, being willing to forgive a multitude of electoral irregularities.

Yet this won’t help build stable states ruled by fairly elected governments. Hasty presidential inaugurations also render legal protests ─ a vital democratic means to address electoral fraud ─ irrelevant.

Africa’s civil society organisations and citizens must continue to raise their voices and cast their votes for the governance they deserve. But without strong governance institutions and electoral management bodies, and an AU brave enough to condemn leaders who flout their constitutions, Africa could continue to be plagued by recurrent violence arising from elite power battles.