Summary

- The debt burden is rising in Africa. Several countries are in debt distress. Others have defaulted on their debt, including three which or are undergoing debt treatment under the G20 Common Framework.

- The G20 supports reducing debt vulnerabilities, having established the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and the Common Framework for Debt Treatment beyond the DSSI. It has stated its commitment to enhanced global safety nets and debt transparency.

- African leaders have also emphasised their interest in reviewing credit risk ratings, enhancing debt transparency, strengthening the Common Framework and restructuring the global financial architecture.

- With the AU now a permanent member of the G20, it can help reshape the G20 debt agenda for Africa by encouraging:

- support for AU initiatives, such as the Africa Credit Rating Agency, Africa Debt Monitoring Mechanism and Africa Financial Stability Mechanism;

- restructuring of multilateral development banks, targeting the needs of developing countries;

- having the AU as a standing member of the creditor committee under the Common Framework where any African country is involved; and

- enhanced debt transparency by setting up the African Debt Monitoring Mechanism.

Executive summary

The debt burden is rising in Africa, with several countries in debt distress. Others have defaulted on their debt services or are undergoing debt treatment under the G20’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments. This comes at a time when the world is experiencing multiple shocks, disrupting economies’ recovery from the pandemic. Global growth rates are yet to return to pre-COVID-19 levels. In response, African leaders have expressed their intention to address debt issues. Possible steps in this regard are reviewing how country credit ratings are set; increasing transparency in how they are reviewed and updated, as well as of debt data and reporting; calling for a strengthening of the Common Framework; and restructuring the global financial architecture. This policy insight focuses on key debt priorities and makes proposals on areas that require further support by the G20, in addition to the actions taken so far.

Introduction

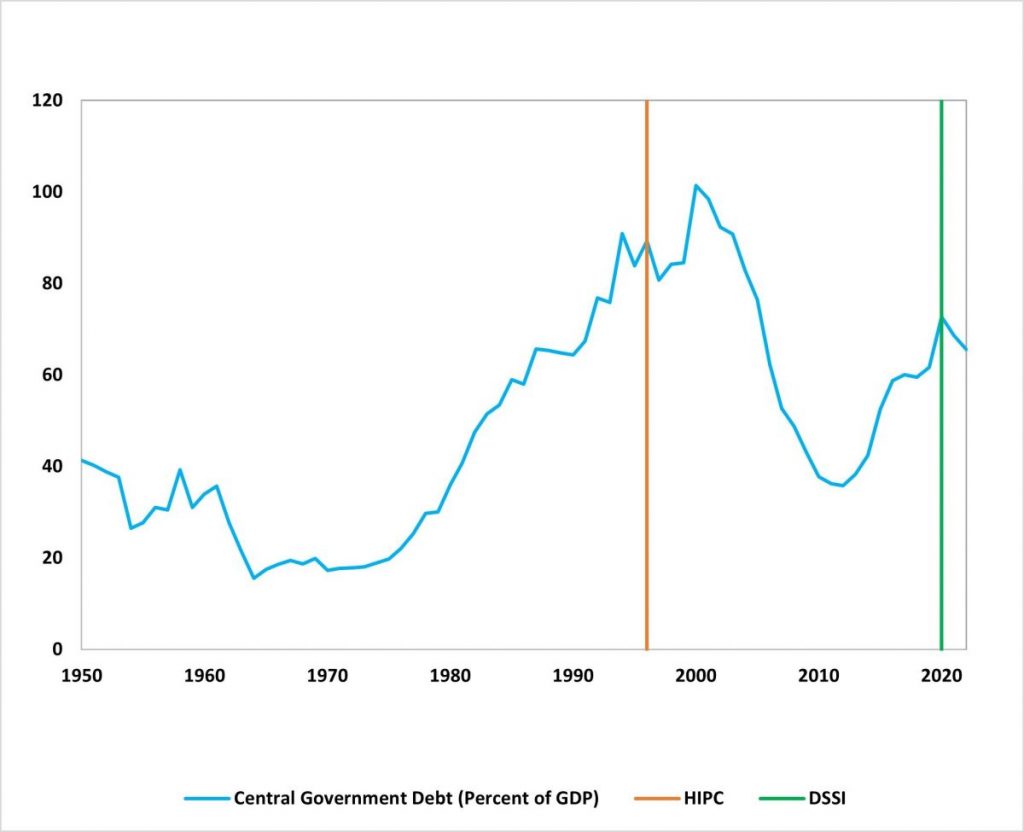

In 2022, Africa’s public debt amounted to 65.6% of gross domestic product (GDP). While this debt is rising, it has yet to reach the levels (89.3%) of 1995 (Figure 1), which triggered debt relief through the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative. Nonetheless, except for Nigeria and Rwanda, all African countries that had completed the HIPC also participated in the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in 2020, an indication of the region’s growing debt burden. With eight African countries in debt distress and 13 under a high risk of debt distress,1African countries in debt distress are the Republic of Congo, Ghana, Malawi, São Tomé and Príncipe, Somalia, Sudan, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The African countries under high risk of debt distress are Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and South Sudan. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/dsalist.pdf this is becoming a policy challenge. Ghana, Zambia and Mali have defaulted on their debt service repayments while Ethiopia, Zambia, Ghana and Chad are undergoing debt treatment under the Common Framework.

Figure 1: Trends in Africa’s public debt as a share of GDP (%)

Source: International Monetary Fund, “Central Government Debt: Percent of GDP”, 2020

The composition of debt on the continent has changed over the past 25 years. A growing number of African countries began issuing sovereign bonds after South Africa had issued the first bond in 1995, with over 20 doing so by 2023.2The International Capital Market Association https://www.icmagroup.org/market-practice-and-regulatory-policy/secondary-markets/bond-market-size/ Of the countries issuing sovereign bonds, 60% are lower-middle-income countries and only three are low-income countries. Of the lower-middle-income countries, two are in debt distress and have applied to the Common Framework and two are under high risk of debt distress. While all these countries have bounced back to pre-COVID-19 growth rates, they are yet to reach the growth levels achieved in the decade before the outbreak of the pandemic (Figure 2). On average, low-income countries have performed better than middle-income countries.

Figure 2: Average growth rates for African countries by income group (2005-2023)

Source: IMF, “World Economic Outlook Database”, October 2023

Note 2005-2014 is the average growth rate and 2023 is a projection.

The G20 has declared its support for reducing debt vulnerabilities. In 2020, it established the DSSI, to allow eligible countries to temporarily suspend their debt service payment, and the Common Framework.3The DSSI was a temporary institutions established from April 2020 until the end of 2021. The Common Framework followed the DSSI and works on a case-by-case basis and has the vocation to be a permanent fixture. Most G20 members support making the Common Framework more inclusive by extending its coverage to middle-income countries facing significant official debt restructuring, providing a well-defined procedure for addressing debt challenges and introducing a sovereign debt authority that is both representative and inclusive. This authority is to be tasked with developing and implementing a comprehensive global framework for sovereign debt restructuring. In addition, the G20 has demonstrated its commitment to enhancing global safety nets and promoting debt transparency to enhance smooth debt restructuring. Similarly, African leaders have expressed their support for addressing debt matters. This can be done by reviewing how country credit ratings are set, as well as the transparency attached to how they are reviewed and updated; enhancing the transparency of debt data and reporting; calling for a strengthened Common Framework; and restructuring the global financial architecture.4UN, Task Force of the Executive Committee on Economic and Social Affairs, Towards a New International Financial Architecture, Report (New York: UN, January 21, 1999).

This policy insight focuses on key debt priorities and makes proposals on areas that require further intervention by the G20, in addition to the actions taken so far.

Priority debt issues for Africa

Rising debt burden, complex debt composition and weakening debt sustainability

Whereas the increase in African debt stock over time is not necessarily a problem per se, the high cost of servicing that debt is. Interest payments have increased with the depreciation of exchange rates because of the tightening of monetary policies in advanced economies, as well as the increased share of non-concessional debt and weakened fiscal buffers. The number of countries with interest payments of over 10% of revenue rose from nine in 2010 to over 20 in 2022. 5UN Global Crisis Response Group, A World of Debt: A Growing Burden to Global Prosperity, Report (New York: UN Global Crisis Response Group, July 2023).This implies that several countries are using their meagre resources to service debt instead of supporting productive economic activities or addressing socio-economic needs.

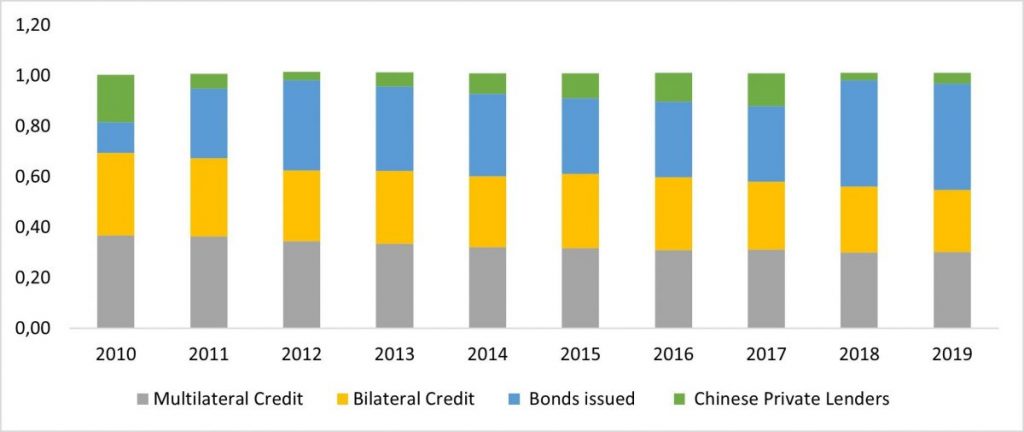

Over time, the composition of debt has become more complex (Figure 3). Historically, multilateral and bilateral public creditors such as the Paris Club held a considerable share of African external debt.6This section focuses on external debt but it is important to acknowledge the significant impact of domestic debt on increased indebtedness of many African countries. However, the share of private creditors has grown significantly, reaching over 40% of Africa’s total external debt currently.7UN Global Crisis Response Group, A World of Debt: A Growing Burden to Global Prosperity, Report (New York: UN Global Crisis Response Group, July 2023) Furthermore, bilateral debt has extended beyond the Paris Club to include debt from China, Saudi Arabia, India and the United Arab Emirates. These dynamics pose complications, as there cannot be a prompt and orderly restructuring of debt without a clear creditor coordination framework that brings all parties together. That said, a significant proportion of these creditors are members of the G20.8The 13 G20 members who are bilateral creditors (in order of debt shares) are: China, France, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Italy, Russia, Turkey, Germany, Canada, Belgium, the UK, Brazil and the US. While the Common Framework is a step in the right direction, it does not include these private The 13 G20 members who are bilateral creditors (in order of debt shares) are: China, France, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Italy, Russia, Turkey, Germany, Canada, Belgium, the UK, Brazil and the US.editors in the creditor committee.

More importantly, the soaring debt burden is coming at a time when the world is experiencing multiple shocks that are disrupting recovery from the pandemic. Global growth rates are yet to return to pre-COVID-19 levels. As stated earlier, developed countries’ monetary policies are tightening global financial conditions, resulting in reduced financial flows and costlier debt. Furthermore, many middle-income countries are struggling to achieve a sustained recovery.

Figure 3: Trends in debt composition in Africa

Source: UN Global Crisis Response Group, A World of Debt: A Growing Burden to Global Prosperity, Report (New York: UN Global Crisis Response Group, July 2023)

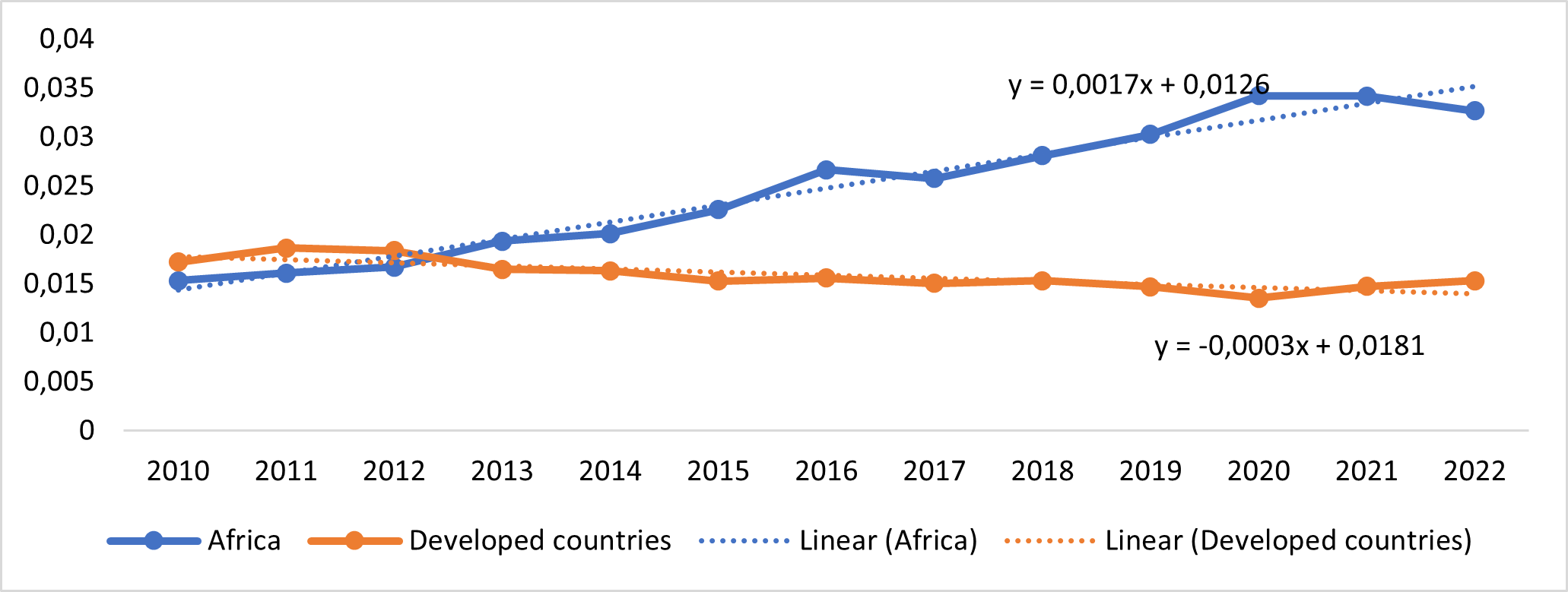

In Africa, interest payments account for 3.2% of GDP, as compared to 1.5% of GDP in developed countries (Figure 4). The share of highly concessional financing has been continuously declining over the past decade. 9Prasad, A., Sedlo, Z., and Massingue, A. C. A 2022. Doubled in a decade: Debt trends in Eastern and Southern Africa demand decisive reform, World Bank Blog. https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/doubled-decade-debt-trends-eastern-and-southern-africa-demand-decisive-reformAs a result, African countries are dedicating a greater share of their budget towards servicing and paying down debt, at the cost of social and development spending. For example, the ratio of public debt interest payments to health expenditure was 147% in the 2019–2021 period, pointing to bleak prospects for Africa in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals.10UN Global Crisis Response Group, A World of Debt.

Figure 4: Trends in interest payments as a share of GDP

Source: UN Global Crisis Response Group, A World of Debt

Debt sustainability has worsened, with several countries having surpassed all sustainable debt thresholds. Despite most of the countries going through the DSSI they are still carrying a heavy debt burden. As such, alternatives to addressing the debt burden are needed, including debt relief, debt forgiveness, debt restructuring and the extension of debt repayment periods.

Funding squeeze and global safety nets

The tightening global financial conditions limit access to international capital markets, making it harder to raise funds for development projects and to refinance existing debt on favourable terms. For example, in March and April 2022 Nigeria and Angola raised $1.3 billion and $1.8 billion respectively, while in the second half of 2022 not a single sovereign bond was issued. Furthermore, in the first half of 2023 two sovereign bonds were issued by Egypt and Morocco. This illustrates the big funding squeeze the continent is experiencing amid various global shocks.

With COVID-19, multilateral development banks (MDBs) increased access limits so countries could access much-needed funding in coping with the effects of the pandemic. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) modified Emergency Fund access limits to respond to urgent balance of payments problems. The enhanced cumulative access limit for the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) was extended until the end of June 2024, while the limit for the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) will be maintained until the completion of the comprehensive review in 2024/25.11IMF, “Debt Relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative”, https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2023/Debt-relief-under-the-heavily-indebted-poor-countries-initiative-HIPC Moreover, in 2023 General Resource Account (GRA) access limits were increased for 12 months. Now that Stage 1 fundraising has closed the subsidy and loan resources gaps in the Poverty Reduction Growth Trust (PRGT), there is a case to consider aligning access limits with those of the GRA.

The IMF also established the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) to help eligible low-income countries, small states and vulnerable middle-income countries address longer-term structural challenges that pose macroeconomic risks, including those stemming from pandemics and climate change. However, the conditionality for access is limiting, as a country can only access it if it has a concurrent IMF-supported programme (upper credit tranche programme) with at least 18 months remaining. Further, the pandemic preparedness aspect of the trust is yet to be operationalised, with borrowing exclusively aimed at climate funding. Only a few countries in Africa have managed to access the RST, namely Kenya, Morocco, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal and Seychelles.

Growing debt vulnerabilities

Globally, several initiatives to address debt vulnerabilities have been implemented since 1996. At that time, the debt-to-GDP ratio had hit 89.3%, triggering the HIPC. Thanks to the debt relief supplied, debt levels dropped to 35.8% by 2012. However, the debt ratio again increased to 72.7% in 2020, when COVID-19 struck.12Kose, M.A., Nagle, p., Ohnsorge, F. and Sugawa, N. 2021. What has been the impact of Covid-19 on debt? Turning a wave into a tsunami. World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 9871. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/801991638297695658/pdf/What-Has-Been-the-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Debt-Turning-a-Wave-into-a-Tsunami.pdf. The DSSI, established in 2020 and extended to December 2021, saw the debt ratio decline to 65.6% in 2022. The DSSI allowed eligible countries to temporarily suspend debt service payments to official bilateral creditors, freeing up financial resources for these countries to respond to the immediate health and economic crises caused by COVID-19. While it provided some relief to low-income countries during the early stages of the pandemic, it was not a comprehensive solution to the debt burden many countries were facing. African leaders have since called for a more enhanced DSSI to provide a roadmap for debt relief and debt restructuring.

The Common Framework was established in 2020. Chad was the first to apply, in January 2021, with the process completed in December 2021. Zambia, which applied in February 2021, took almost two years to get to the agreement point (in June 2023). Other countries that have applied include Ethiopia and Ghana. It is crucial to make the framework more effective, time bound and transparent, allowing more countries in debt distress to benefit from it. This can be done by defining clear steps and timelines, expanding the creditor committee to private sector creditors to smooth coordination challenges, establishing a comparability treatment formula to minimise technical disputes and making use of the IMF’s lending into arrears policies to reduce the leverage of holdout creditors. In addition, the framework should be expanded to middle-income countries.

Credit rating risk

There is a perception that credit rating agencies such as Fitch, Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s give biased assessments of African economies. A recent study by the UN Development Programme13UN Development Programme, “More Objective Credit Ratings Could Save Billions For African Countries’ Development”, April 17, 2023. showed that African countries could save up to $74.5 billion if credit ratings were based on less subjective assessments. African countries also feel that the ‘big three’ rating agencies are quick to downgrade a country’s rating and slow to upgrade when upgrades are due. There is thus a need for systemic change. In the first six months of 2023, many countries had their risk profile downgraded, which makes acquiring debt more expensive. As a result, the AU is establishing an alternative African credit rating agency to address the alleged issues of lack of objectivity, consultations and herding behaviour at the ‘big three’. The African Credit Agency is set to be launched in early 2024. This will provide an alternative rating that investors and creditors can use for comparison when making decisions regarding the continent.

Transparency in debt management

Debt transparency and reporting is critical for sound macroeconomic stability, public financial management and dealing with the risks associated with debt portfolios. Further, it helps to develop sound and sustainable lending policies and implement restructuring options, should the need arise. Without transparency, the risk premium for a country increases, which in turn increases the cost of borrowing. Hidden debt is growing, especially with diversified lenders beyond the traditional G20 creditors.

Using the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment rating for debt policy and the quality of budgetary and financial management, it is clear low-income African countries’ ability to manage their debt has not changed significantly in the past decade. In some cases, it has deteriorated, implying that a lot more is needed to strengthen capacity for debt management, including addressing hidden debt.

While debt ceilings dictate the maximum amount a government can borrow, they have not safeguarded African countries from a growing debt burden. Such ceilings are usually established by the public debt management laws, with limits expressed either as a percentage of GDP or as an absolute amount. This may be because there are no clear mechanisms to monitor fiscal situations.

Kenya, for example, has converted its debt ceiling from absolute terms of KES14Currency code for the Kenyan shilling. 10 trillion (approximately $60 billion) to Present Value of 55% of GDP.15Parliament of Kenya, http://www.parliament.go.ke/crucial-debt-achor-bill-assented-law http://www.parliament.go.ke/crucial-debt-achor-bill-assented-law In some countries, such as Zambia and Cabo Verde, Parliament is allowed to increase the borrowing limit when approving the annual national budget, especially in times of emergency. In Kenya, according to section 50(5) of the Public Finance Management Act of 201216The Public Finance Management Act 2012, https://www.treasury.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Public-Finance-Management-Act-2012.pdf, Parliament provides thresholds for the borrowing entitlements of the national government, county governments and their entities. Only Parliament can revise this, as well. Other African countries with debt ceilings are Angola, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, South Africa, Mozambique, Eswatini, Namibia, Lesotho and Botswana, whose debt ceilings are capped at 60% of GDP by SADC. The East African Community has also set a debt limit of 50% of GDP for its member states.

G20 and African leaders’ response to the debt issue

The G20 has stated its support for reducing debt vulnerabilities, enhancing global safety nets, making the Common Framework work better and promoting debt transparency and reporting. At the same time, African leaders have indicated their focus on negotiating debt relief, extended repayment periods, tightened debt management and enhanced global safety nets.

Strengthening global safety nets

In transforming the governance of international finance institutions, the G20 will revisit the adequacy of quotas in IMF governance under the 16th General Review of Quotas, including having a new quota formula by 15 December 202317G20 Indonesia 2022, “Bali Leaders’ Declaration”, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/60201/2022-11-16-g20-declaration-data.pdf. In addition, it is enhancing global safety nets by scaling up the PRGT and RST to provide affordable long-term financing for low-income countries in Africa. This includes supporting voluntary contributions to the RST and calling for additional pledges and timely contributions to the PRGT subsidy resources to meet funding needs.

African leaders have also called for an increase in the PRGT annual access limit to 200% and the cumulative access limit to 600% to align with the revised access limits for the GRA. Similarly, the IMF supports an extension of the enhanced access limits for the RCF and RFI and streamlining the RST requirements to increase uptake by African countries in high risk of debt distress.

Further, the G20 is advocating more headroom and concessional finance to boost the World Bank’s capacity to support low- and middle-income countries by replenishing the twenty-first International Development Association (IDA21) and boosting the IBRD headroom respectively.

The G20 has declared its willingness to exploring viable options for countries to voluntarily channel special drawing rights (SDRs) through MDBs such as the African Development Bank and has also urged for implementation of the recommendations regarding capital adequacy frameworks in advancing MDBs reforms. However, African leaders cautions that Capital Adequacy Frameworks should not result in a significant hardening of lending terms. Instead, their financing models should be adapted to avoid unintended consequences for the debt sustainability of African countries.

Easing the debt burden

The G20 has reiterated the need to implement the Common Framework in a predictable, timely, orderly and coordinated manner. Further, it is encouraging the efforts of the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable participants to improve communications and foster a common understanding among key stakeholders, both within and outside the Common Framework, in facilitating effective debt treatments.

This reinforces the call by African leaders for an effective Common Framework with an expanded creditor committee that includes private creditors, establishing a formula for comparability of treatment and allowing debt payments to be on standstill during the period of negotiations. In the long run, the hope is to establish a more inclusive multilateral creditors club where all partners, including Paris Club and non-Paris Club members, effectively engage under the Common Framework.

Also, African leaders are calling for improved debt restructuring frameworks by enhancing the transparency of loan terms and contracts. They are also appealing for accelerating reforms that support the extension of eligibility of highly indebted middle-income countries in Africa and ease aggressive limits on non-concessional borrowing.

In addition, African leaders have called for equitable, comprehensive and sizable debt relief, given the growing number of African countries facing debt distress18African Caucus 2023, “The Sal Declaration”, https://africancaucuscaboverde.gov.cv/api/uploads/The_Sal_Declaration_67775ca17a.pdf. In addition, consideration should be given to extending the debt repayment period to give the countries in distress adequate time (a decade) to repay and build their economies.

Enhancing transparency in debt management

The G20 welcomes the joint efforts by all stakeholders, including the private sector, to continue working towards enhanced debt transparency.19G20 Indonesia 2022, “Bali Leaders’ Declaration”, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/60201/2022-11-16-g20-declaration-data.pdf It encourages a voluntary stocktaking exercise of data sharing with international financial institutions. Additionally, it welcomes the efforts of private sector lenders that have already contributed data to the joint Institute of International Finance/OECD Data Repository Portal. It also continues to encourage others to contribute on a voluntary basis.

During the Africa Climate Summit in September 2023, African leaders agreed to adopt an African Debt Monitoring Mechanism by June 2024. This will serve as a platform for the AU to access information on debt to help countries engage in debt negotiations in line with Agenda 2063. They have also stated their support for addressing illicit financial flows, tax evasion and avoidance, trade misinvoicing and transfer pricing, while facilitating stolen asset recovery and strengthening the capacity of public revenue-earning entities to boost domestic resource mobilisation.

Conclusion and way forward

The inclusion of the AU in the G20 is a timely and welcome move in addressing the continent’s deepening debt issue. Through its membership, the AU can increase its visibility in the global arena and exert more influence in terms of decision-making and implementation. More importantly, it gives the AU an opportunity to reshape the G20 debt agenda for Africa.

Key areas of priority that the AU should pursue with the G20 include the following:

Supporting AU initiatives

Various initiatives are already in the pipeline that require support, including the proposed Africa Credit Rating Agency, the Africa Debt Monitoring Mechanism and the Africa Financial Stability Mechanism. Supporting their establishment and operationalisation will go a long way in addressing debt vulnerabilities and enhancing liquidity buffers for Africa.

Restructuring MDBsa

The ongoing governance reforms under the 16th general review of quotas anticipated to be finalised by 15 December 2023 should aim to strengthen Africa’s voice by adding a 3rd chair. In addition, is considering a formula for distributing SDRs allocations, including through re-channelling the same to MDBs that target the needs of developing countries.

Easing the debt burden

Debt relief remains a key option for consideration in easing the debt burden for Africa. In addition, agreeing on how to extend the debt payment period is equally crucial. Most importantly, Africa should come up with strategies to address the growth trap in which middle-income countries find themselves.

Making the Common Framework work better to support countries in debt distress and at high risk of debt distress remains a priority. This includes coming up with a clear timeline and steps to follow in the process, as well as including private creditors in an expanded creditor committee. It is also crucial to support countries using the framework to prepare effectively to avoid delays in reaching agreement and having a sustained and comprehensive debt service repayment standstill for the duration of negotiations. Further, it is vital that the AU be a standing member in the creditor committee when African countries are involved.

Alternative credit rating agency

There should be a review of the sovereign credit rating process to remove any biases. This includes addressing transparency and regulatory issues. Moreover, supporting the proposed African Credit Rating Agency to ensure it gains credibility as an alternative to the traditional credit rating agencies should be a priority for the AU.

Enhancing debt transparency

It is important to enable the African Debt Monitoring Mechanism to increase transparency in debt reporting. Significant support is required from international financial institutions for transparent data sharing, including with the OECD Data Repository Portal. In addition, building the capacity of African countries to establish and strengthen their debt management units for effective debt management should also be pursued.