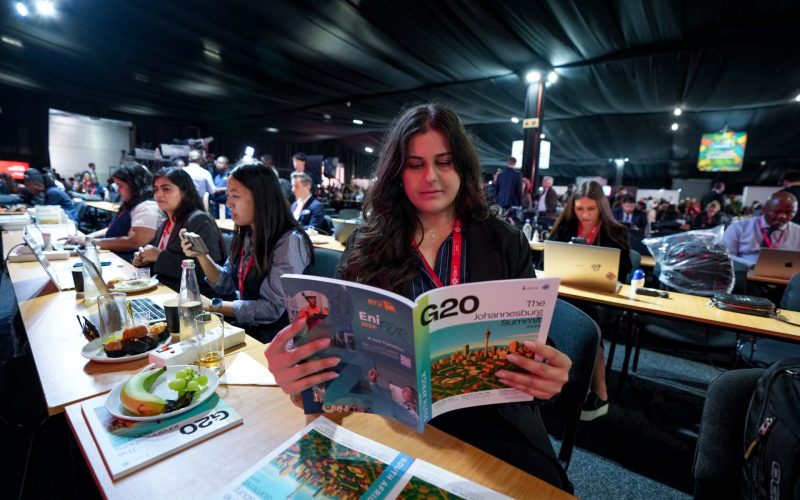

Taking over from three Global South presidencies of the G20, South Africa’s agenda in 2025 built on those of Brazil, India, and Indonesia, while emphasising African concerns as the first African G20 presidency. Its agenda has amplified key developmental concerns requiring international cooperation at a moment when some countries are contesting both development and cooperation.

Although the G20 was originally a grouping of finance ministers, established after the Asian financial crisis of 1998, its agenda has grown since 2008, when it was elevated to heads of state. As global challenges, such as climate, pandemics and inequality have become more acute, the need to bring development to the forefront has become essential, although not always easy. South Africa’s themes of “Solidarity, Equality and Sustainability” reflect the trend in the Global South presidencies to re-centre development in global discourse.1G20 South Africa, 2025.

South Africa set an ambitious agenda. From tackling the high cost of capital in African economies to ensuring a just energy transition, advancing the Sustainable Development Goals, tackling inequality, promoting women’s empowerment, and ensuring debt sustainability, South Africa has not shied away from issues that are increasingly being contested across the world and in G20 countries.

The complex geopolitical context makes agreement on some of these extremely difficult. However, there have been some wins. A set of voluntary principles on combating illicit financial flows (IFFs) was adopted by the development ministers that recognised the linkage between IFFs and the erosion of domestic resource mobilisation, which has become more urgent in a climate of declining aid. There was also a ministerial statement on debt sustainability, which reaffirmed their commitment to strengthen the Common Framework on Debt treatment, and support for the ongoing review of the debt sustainability frameworks by the IMF and World Bank. During a year where several working groups issued only a chair’s statement, the ability to have a statement on debt was symbolically important even if there was no major innovation on plugging already identified weaknesses regarding the Common Framework.

The spotlighting of debt sustainability has brought renewed attention to the proposals incorporated into the Compromiso de Sevilla, particularly the establishment of a borrowers’ club, around which preparatory work has already been undertaken in New York. The club is likely to be launched in 2026.2 United Nations, FFD4 Outcome Document: Sevilla Commitment, July 2025.

Recognising the crucial role of critical minerals in Africa, especially in contributing to industrialisation, the Summit will likely adopt a G20 Critical Minerals Framework. This framework would mainstream the importance of local beneficiation and value addition at source, while also recognising the asymmetry in exploration capabilities between advanced and developing economies. In parallel, a set of voluntary principles on sustainable industrial policies has been developed, emphasising the link with inclusive economic growth, industrialisation, jobs, and equality.

Yet, the legacy of South Africa’s presidency goes beyond these outcome documents. There are several issues that SA advocated that have contributed to a more nuanced debate on the challenges of development. This includes the initial proposal for a commission on the cost of capital, intended to address the issue of the African risk premium. While this was not established, this issue received significant coverage in global forums, including in the Fourth Financing for Development conference. Relatedly, SA’s work on combating illicit financial flows was reflected in the Compromiso de Sevilla. While the commission was not established, South Africa appointed an African Expert Panel that focused on the interconnection between growth, debt and development, and issues related to the high cost of capital in Africa. Its recommendations include, among others: launching a new G20 debt financing initiative for low-income and vulnerable countries and reforming the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) allocation system, which reduces the discretionary and political nature of the current allocation process.

South Africa has also sought to build consensus on the concept of global public goods. While there was only a chair’s statement on a set of principles relating to global public goods, South Africa will be establishing an Ubuntu commission focused on fostering international cooperation for the protection and delivery of global public goods.

The establishment of an expert panel on inequality, chaired by Joe Stiglitz and presented to president Ramaphosa in early November, aimed to synthesise the research on this issue. It proposes the creation of an International Panel on Inequality, modelled on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, to function as a technical advisory body.

However, South Africa’s G20 presidency has had to contend with difficult geopolitical headwinds and a fraying bilateral relationship with the US. The US chose to participate only in some of the meetings of the various working groups and task forces, with the Trump administration making it clear that it considered the priorities of the SA presidency as contrary to the interests of the US. In recent weeks, President Trump has made it clear that not only will the US not attend the summit in Johannesburg, it will also oppose the issuing of a Leaders’ Declaration, as the absence of the US would mean that there was no consensus in the group.3BBC News, US to boycott G20 in South Africa, Trump says, November 2025.

The G20 operates on the basis of consensus, requiring all members to agree on the final text. This approach necessitates compromises by all members so that the outcome reflects a set of common political commitments, even though there is no enforcement mechanism and these are voluntary. However, the position that the US has taken is unprecedented. The underlying assumption for consensus-based decision-making is that countries are willing to negotiate in good faith and make trade-offs so as to arrive at an outcome. When countries eschew this approach because they do not want a Declaration, it raises questions about the principle of consensus; it gives the power to one country to veto the entire process, where member states have spent weeks negotiating the Declaration. It also sets the precedent that other countries can do the same in future if they do not agree with the host country or are opposed to its place within the group. Such an approach would undermine the constructive role that the G20 can play as a forum for fostering understanding and compromise, even in a context of heightened power rivalries.

In an era when many accepted principles of international cooperation are being questioned and undermined, how member states secure the G20 platform as a forum for dialogue and coordination on common challenges will contribute to the future trajectory of multilateralism.

This article was first published by the Foreign Policy Centre.