AGOA and the US – African trade relationship has been placed under the spotlight in recent months, particularly with regards to the extension of the Act towards September 2015 and around South Africa’s continued benefits under the programme (as the largest AGOA beneficiary).

AGOA, unlike other preferential trade deals, is a unilateral trade deal that allows least developed and developing countries from Sub-Saharan African (SSA) additional market access in the US. AGOA extends duty free and quota free access to the US market on roughly an additional 2000 Harmonised System product lines, above and beyond the 3800 lines that are duty free under the US’ most-favoured nation offering, as well as the 3400 lines under its General System of Preferences (GSP) programme. While AGOA is a non-reciprocal and unilateral agreement (ie. countries do not have to concede market access to the US), it is not without conditions. In order to benefit under AGOA, the US requires countries to comply with a broad range of conditions such as respecting and promotion of the rule of law, respecting human and workers’ rights, and upholding democratic and market-based economic principles. AGOA eligibility criteria also dictate that barriers to US trade and investment should be removed.

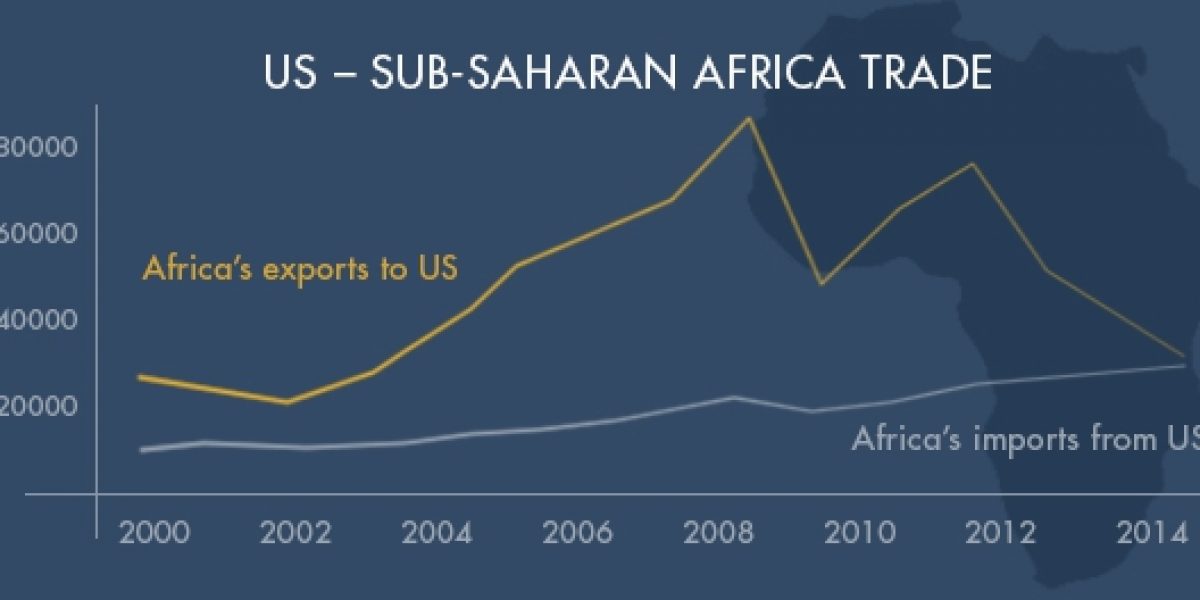

The impact of AGOA has been significant: between 2000 and 2008, exports from SSA countries to the US increased from $22 billion to $82 billion. Despite a brief decline in trade following the global recession, exports totalled $72 billion in 2011, before declining again due to a drop in oil exports from the continent. By 2015 exports had decreased radically, totalling $19 billion in 2015, eroding a strong positive trade balance for African countries. Nevertheless, AGOA has been successful in diversifying exports from Africa. Apart from oil, key exports include vehicles (31% of non-oil exports in 2014), followed by apparel (28%), iron and steel (17%) and aluminium (11%). While energy-related exports dominate exports for countries such as Nigeria and Angola (roughly 99% for both countries), non-oil producing states such as Kenya and Lesotho have successfully managed to grow their exports under AGOA. South Africa in particular has been able to leverage AGOA to grow its exports to the US in sectors other than natural resources; notably the automotive, chemicals and agriculture sectors (accounting for 28%, 14% and 6% of total exports in 2014, respectively). Between 2000 and 2014, South Africa doubled the value of exports to the US, totalling $8.27 billion in 2014, of which nearly 40% benefited from AGOA and GSP preferences.

Watch a video with Florizelle Liser and Sharon Bomer Lauritsen on the key points raised at the event.

AGOA, originally set to expire in 2005, has twice been renewed for five-year periods (in 2005 and 2010) and was extended in 2015 for a further ten years, to expire in 2025. South Africa’s continued participation under the AGOA programme was especially contested ahead of the latest extension. Some argued that the continent’s most advanced economy should graduate from AGOA, while it was also perceived that the country imposed barriers to US trade, particular for US meat exports. Ultimately South Africa remained a beneficiary of this programme. Given the extension of South African value chains throughout the region, it was determined that excluding the country would have a detrimental effect on other economies on the continent. However, specific provisions were put in place in the renewed AGOA to review the eligibility of countries on an ongoing basis if they do not comply with AGOA criteria.

South Africa was the subject of the first of these so-called ‘out-of-cycle’ reviews. American businesses, through their representatives in Congress, contended that South Africa did not comply with the AGOA criteria, especially with regards to eliminating barriers to trade and investment. While various grievances towards planned legislation in South Africa restricting US investment in the securities industry, as well as proposed changes to intellectual property rights were discussed, it was ultimately long-standing barriers imposed by South Africa on US meat imports that led to possible suspension of AGOA benefits for the country.

South Africa has, for more than a decade, imposed anti-dumping duties on US chicken exports. The country contends that US producers want to export chicken pieces that are undesirable in their domestic market, to South Africa. While the contentious cuts (brown meat cuts such as drumsticks) are undesirable in the US market (and therefore unsellable), authorities argue that US producers can export these to South Africa below cost and still make a profit, resulting in unfair trade and competition. As a result, South Africa has imposed an anti-dumping duty (roughly $0.60 per kilogram) on US chicken exports above the standard duty of 37% that such exports already attract. After a nearly 15-year standoff on this issue, involved parties negotiated a duty free quota of 65 000 tons in the middle of last year (comparatively modest considering the country imported more than 450 000 tons in 2015). However, slow progress on the implementation of this agreement by South Africa ultimately led to US President Barack Obama notifying Congress and Pretoria that he planned to suspend South Africa’s benefits under AGOA within 60 days if outstanding issues were not addressed.

Following a period of intensive negotiations between US and South African counterparts, South African Trade and Industries Minister Rob Davies announced that all outstanding technical and health and safety issues had been resolved. This was followed by another declaration from President Obama that unless the negotiated agreement were implemented (evidenced by US chicken exports on South African shop floors) by mid-March 2016, South Africa would lose trade preferences extended under AGOA for its agricultural exports.

Reports towards mid-February indicated that US poultry products were ‘on the water’ to South Africa. Thus, unless there are any unexpected administrative hiccups, South Africa will maintain full benefits under AGOA. Nevertheless, the poultry-saga has highlighted a number of key concerns for South Africa and other SSA countries under the current (unilateral) trading regime with the US.

Firstly, given that AGOA is an Act of US Congress rather than an agreement, there is no clear and transparent legal dispute resolution mechanism as found typically under negotiated trade agreements. Instead, the US can unilaterally extend or remove AGOA, with crippling results for countries. Madagascar experienced this first hand in 2008 when the US rescinded their benefits under AGOA following political turmoil in the country. A thriving textile and clothing industry, grown largely as a result of exports to the US through AGOA, saw activity in this sector drop significantly resulting in massive job losses and disinvestment leading to increased poverty in the country. A similar scenario is currently playing out in Swaziland after the country saw their AGOA status removed in 2015 following a failure to address the US’ concerns over worker rights violations in the country.

Secondly, the ‘poultry affair’ has created a form of blueprint on how future issues could be handled, employing AGOA as leverage, both in South Africa and other SSA countries. Although the US has in similar poultry-related disputes with China followed recourse through the WTO’s dispute resolution mechanism, they have opted in the case of South Africa to rather employ AGOA – as this programme arguably provided greater leverage. As highlighted earlier, the US has other concerns in South Africa including the issues related to the proposed Private Security Bill and with copyright and intellectual property rights in South Africa. Both these bills have passed the South African parliament and are awaiting signature from South African President Jacob Zuma. Once signed, a repeat of the ‘poultry saga’ could be on the cards. In an attempt to avoid future suspension of AGOA benefits for the country, the poultry ‘deal’ included a clause that would suspend the rebates offered to US poultry exporters if the country were to lose any benefits under AGOA. This bargaining chip is arguably small for South Africa given the significant power imbalance in US-SA economic relations.

Thirdly, the poultry dispute and the ensuing negotiations, as well as previous experiences with negotiated trade agreements, have shown that such processes require significant technical expertise and are timeous. Negotiations between South African and US counterparts involved multiple departments and ministries (eg. trade, health, and animal and environmental among others) on both sides, in addition to consultations with private sector stakeholders. While South African authorities have done an admirable job throughout the negotiations, striking a balance of trade promotion while protecting national interests, few African countries have such capacity.

This latter observation is especially relevant in light of indications from the US that they would like to pursue reciprocal trade agreements with African countries after the current AGOA extension comes to an end in 2025. Arguments against AGOA’s latest extension pointed to the European Union (EU) who signed reciprocal trade agreements with African countries under the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA). In addition, the US, along with numerous other countries, has become increasingly frustrated with the lack of progress on trade negotiations in the WTO, due to the stalemate within the Doha Development Round. As a result, the US has been keen on negotiating deals outside the ambit of the WTO, as evidenced by their engagement in the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Currently the US is not lobbying for any specific reciprocal agreement, but looking towards African countries to put forward suggestions. There are a wide range of agreements for South Africa and African countries to consider: Trade and Investment Frameworks, Bilateral Investment Treaties, Preferential Trade Agreements or ultimately a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). The agreement to be made depends on the range of issues up for negotiation (eg. trade in goods, trade in services, investments, etc) and differs in level of complexity.

For larger countries, such as South Africa and perhaps a handful of others, negotiating bi-laterally might be an option (although South Africa will have to negotiate as part of the Southern African Customs Union [SACU] in accordance with the 2002 SACU Agreement). Smaller countries, which will likely have less leverage in negotiations, should look to negotiating within groups. Already a number of key regional economic communities (RECs) exist within Africa that could be used as a basis for negotiations, or ultimately the larger group of the Tripartite FTA or the Continental FTA. Yet, the EU experience negotiating with the respective RECs showed that these regional authorities had little mandate to negotiate on behalf of their members, with negotiations ultimately ending up as quasi-bilateral negotiations.

Another key concern (and threat) for smaller African countries remains the attractiveness of AGOA and resulting over-reliance on this programme. Countries should recognise that over-reliance on AGOA benefits is not sustainable and holds potential disaster for economies. If these countries fail to diversify their markets, or at the very least their product offering to the US, the ‘free lunch’ enjoyed for 25 years under AGOA will see their economies narrowly intertwined with one partner, resulting in a similar fate to that experienced by Madagascar and Swaziland. Alternatively, they should look to mitigate these negative effects if they proceed with a negotiated agreement, but this will require concessions in other areas of their economies.

Ultimately, while AGOA has been a boon to many African economies, it is likely that benefits enjoyed under the Act will end within the next 10 years. As the AGOA deadline nears, South Africa and other countries in SSA should seriously consider their relationship with the US. While trade and investment ties with the EU were strengthened through signing of the EPAs, and increasingly closer relations are being crafted with emerging economies of the global south, the US will remain the largest global economy for the foreseeable future (and certainly past 2025). African countries cannot neglect this opportunity for engagement, but need to ensure they are adequately prepared.