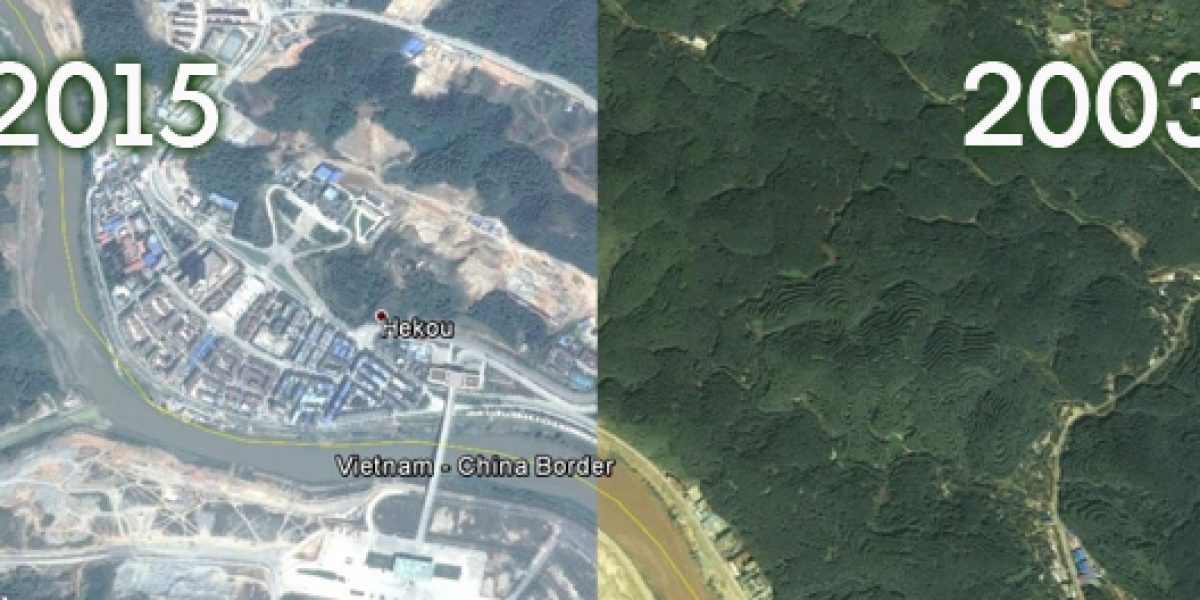

On the opposite side of the country, the town of Hekou sits in dense jungle on the Honghe River, which must be waded across to reach Vietnam. The town of Ruili on the border with Myanmar must contend with the separatist Kachin Independence Army, while the town of Dandong features a bridge to an empty rice field in North Korea.

None of these seem like future centres of economic development, and yet they are all the subject of an ambitious set of projects underway in China and East Asia to develop isolated areas, and to redefine transnational spaces of co-operation. The towns above host four of 47 projects examined in a recent study on Border Development Zones (BDZs). Broadly defined, BDZs are projects to develop border areas, but most are effectively Special Economic Zones that attempt to make use of the advantages offered by the unique economic geography of border towns.

These advantages include well established transport linkages, the presence of important trade-related industries, and – most importantly – different economic structures on either side of the border. Mixing two countries unique economic advantages, such as using one country’s technological prowess and another’s cheap labour, can often result in efficiencies that are unattainable for either country working alone. By taking advantage of these features, BDZs can also directly drive regional integration, providing a forum for co-production between neighbours and developing crucial logistics infrastructure at border towns, thereby spreading the geographic distribution of growth.

BDZs are most commonly set in border towns, but more ambitious efforts are moving the zones to or across the border, creating unique transnational spaces. The Jiegao Free Trade Zone, for example, hugs the China-Myanmar border, allowing direct entry to the zone with easier visa requirements and customs controls. More ambitious still is the Khorgos International Center for Border Cooperation, which physically straddles the border – with 1.85 km/sq in Kazakhstan and 3.43 km/sq in China. It has its own regulations for the movement of goods and people.

In effect these zones mirror tiny independent states: they have their own borders, and their own laws – albeit with ultimate accountability resting with their host countries.

The isolated location of border towns and the complex accountability involved in these distinct legal areas have created challenges, and some of the BDZs have proved disastrous. Efforts to develop a ‘Macau of the Jungle’ on the remote Laotian border at Boten transformed the town into an archetypal Wild West den of gambling, prostitution, and organised crime. The casino that was the zone’s centrepiece attraction began holding indebted clients for ransom, a final straw that compelled China to disconnect the town’s supply of power and water, ending a dreadful (but very exciting) run for the Boten BDZ. Most failures have been far less spectacular, and took the form of expensive investment that yielded little growth.

But many of the results have been impressive. Of those mentioned above: Erenhot has seen its population grow by 66,000 and is now the gateway for 80% of Chinese-Mongolian trade, the Hekou zone plays host to 184 firms accounting for $633 million in trade, and both Ruili and Dandong have become critical trade linkages for their respective neighbouring economies. Perhaps the most impressive example is the development of the Riau Islands, which form the border between Singapore and Indonesia. Seven years after the founding of a BDZ in 1989, the largest island of Batam saw its total workforce grow from 10,000 to 125,000, while investment tripled and exports grew by a factor of 68.

The three aims of BDZs – growth, geographic inclusion, and regional integration – are major challenges for South and Southern Africa, and BDZs offer an innovative tool to confront these challenges. Most pressing is the necessity of extending the benefits of growth to small towns. Small towns represent an unenviable paradox for policymakers. With an underdeveloped commercial base, small consumer markets, inadequate infrastructure, and a depleted workforce – grand efforts to transform small towns look set to fall to an overwhelming economic reality, and to the harsh forces of competition from centres like Johannesburg and Cape Town. And yet these same factors mean that small towns will not develop without some intervention, which – barring a sudden discovery of minerals or investment by a very forward thinking firm – will almost certainly have to come from the state, in partnership with the private sector. To do nothing is to surrender small towns to the geography of historical determinism.

There are challenges to using BDZs in South Africa, including the small size and underdeveloped nature of our neighbouring countries’ economies. But border towns in South Africa are already the focus of zone development, with SEZs planned for both Mahikeng (on the Botswana border) and Musina (on the Zimbabwean border). Bringing elements of BDZs into these pre-existing SEZ projects could add extra punch to their development impact.

How to make BDZs work in Mahikeng and Musina is the focus of ongoing research, but some preliminary suggestions are included in the study. These include: lifting certain visa requirements for firms operating in BDZs, removing rules of origin restrictions for goods traded in the zones, providing special testing and certification facilities, and establishing duty-free retail centres.

With these additions, South Africa’s border SEZs can leverage their unique location to better spread the benefits of growth to new regions.

Co-author: Clarence Siziba