Recommendations

South Africa must lead in revitalising a post-COVID-19 social compact for Southern Africa as a foundational inspiration for Africa’s socio-economic and democratic recovery. Working with an ensemble of key regional partners – the Southern African Development Community (SADC), leading research institutions, civil society organisations, organised labour, the private sector, International Cooperating Partners (ICPs) and multilateral development agencies – South Africa should aim to:

- reshape manufacturing, with a focus on self-reliance;

- sustain momentum in regional and pan-African cooperation;

- close the skills gap;

- address infrastructure deficiencies;

- finance infrastructure;

- set up infrastructure management systems; and

- enhance integrated decision-making.

Introduction: testing the logic of regional integration

Will Southern Africa be better off with more or less integration? Time to close the borders to hostile outsiders and go it alone?

A core assumption held by observers of global affairs is that societies and economies benefit from close cooperation. This is assumed to evolve where interests and values overlap, leading to political and economic integration, benefiting all who participate.1There are four main types and stages of economic integration: a free trade area, a customs union, a common market, and economic union – reflecting ever-increasing layers of integration. In reality, progress from one stage to the next is messy, overlapping, and often contradictory. Regional integration has been a major political and developmental objective of African governments ever since political independence in the 1960s. However, the ‘how’ has lagged. Africa has the most Regional Trade Agreements in the world – 14, of which the AU recognises eight (see: Brendan Vickers, A Handbook on Regional Integration in Africa: Towards Agenda 2063 (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2017)). The AU’s Agenda 2063 is an ambitious plan to advance Africa’s integration along political, economic, developmental and peace and security dimensions.A global political economic system, driven by globalisation is seen as an ultimate outcome. A complementary assumption is that systemic checks and balances (for example, regulation by the World Trade Organisation) tend to reduce capitalism’s excesses. The COVID-19 pandemic has put these assumptions to the test as never before.

For regional integration (or regionalism) to flourish, at least four factors need to be in place: shared political values and common identity, complementary rather than competitive economies, external demand for regional goods and services, and infrastructure to make integration happen.2See: Fredrik Söderbaum and Timothy Shaw, Theories of New Regionalism (New York: Palgrave, 2003) and Vickers, A Handbook on Regional Integration in Africa.These factors exist, in varying degrees, in Africa – a point to which we will return.

The largest regional trade agreements are the EU, the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) replacing the North American Free Trade Agreement from 1 July 2020 and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). The AU’s flagship programme, the African Economic Community has more member countries than the EU, USMCA, and APEC but represents a smaller portion of global trade.

But what happens to regional integration and its underlying philosophy of regionalism – a sense of shared values, identity and destiny – under conditions of severe disruption, such as presented by COVID-19? Sceptics talk of a global political stress test, de-globalisation and a return to geopolitics and hard realism as a result of COVID-19.3Francis Fukuyama, ‘The Pandemic and Political Order’, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-09/pandemic-and-political-order; José Balsa-Barreiro, Aymeric Vié, Alfredo Morales and Manuel Cebrián, ‘Deglobalisation in a Hyper-Connected World’, Nature, 6 No. 28 (2020), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-020-0403-x

Africa

Let us examine the African situation. African countries all participate in regionalisation. By this we mean they agree to cooperate through common institutions and rules to improve market efficiency, share costs of public goods or large infrastructure projects, create a building block for continental and global integration, and reap other non-economic benefits, such as peace and security. In fact, regional cooperation can strengthen the voices of small nations that often face severe disadvantages in dealing with the rest of the world because of their low bargaining power and high negotiation costs.

However, in Africa we witness slow progress.4The African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), The Africa Governance Report (Midrand: APRM, 2019). https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36418-doc-eng-_the_africa_governance_report_2019_final-1.pdfDecades-long interventions and projects to advance regionalisation have culminated, in May 2019, in the adoption by all AU members (except Eritrea) of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA).5The AfCFTA will be governed by five operational instruments: the rules of origin; the online negotiating forum; the monitoring

and elimination of non-tariff barriers; a digital payments system and the African Trade Observatory. See: https://www.tralac.org/resources/our-resources/6730-continental-free-trade-area-cfta.htmlTrading under the AfCFTA was due to commence in July 2020, but, as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic, this date is being postponed (a new date is yet to be confirmed by the AU Commission).

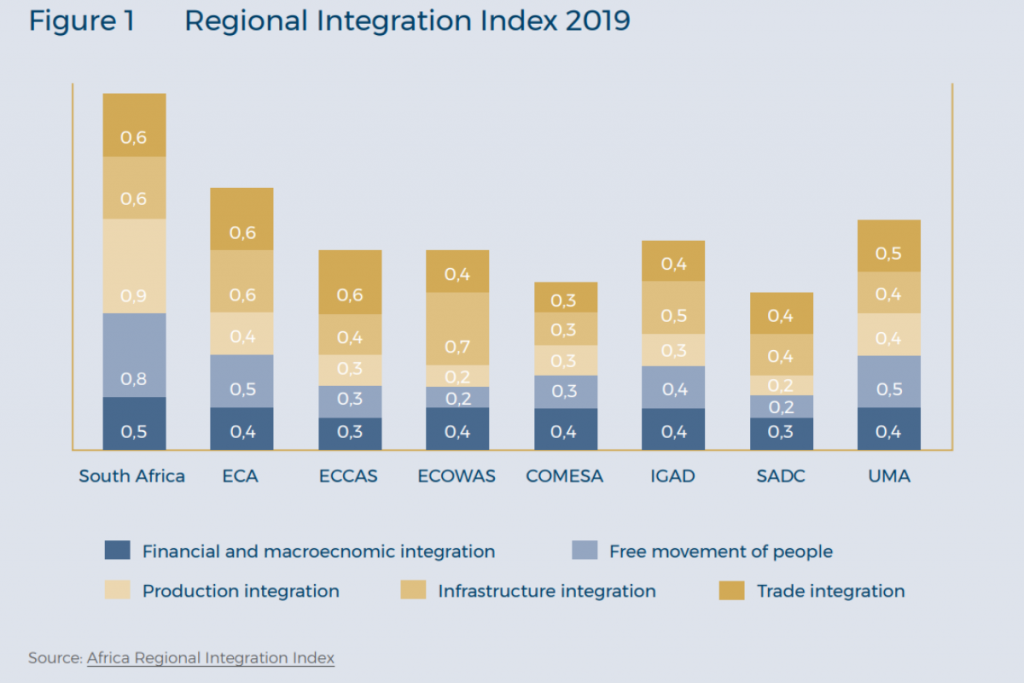

Even before the disruption of the global pandemic, Africa was not performing well. According to the 2019 Africa Regional Integration Index, the level of integration on the continent was low overall, especially on the productive and infrastructural dimensions. SADC had a low average score and nine of its 16 members were classified as average performers. SADC’s average score is largely driven by a gap in regional infrastructure. While South Africa achieves a near-perfect score, the next two performers, Seychelles and Mauritius, score far below and the bottom five performers (the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, and Tanzania) score near zero. Similarly, although the DRC and Tanzania do better on productive integration, where they fall into the average zone, SADC’s average score for productive integration6Productive integration refers to a country’s involvement in regional supply and value chains.is still not much better than for integrated infrastructure.

Indeed, four key COVID-19-induced trends will impact and reshape the contours of Africa’s ambitious regional integration projects: the return to geopolitics and hard realism, the disruption of trade, the erosion of democracy, and the destruction of economies.

Southern Africa

What is the situation with SADC, which is believed to be a prime example of African regionalisation, given its image of relative stability and that it is imbued with a powerful regional actor, South Africa?

The 16-member SADC was established as a development coordinating conference (SADCC) in 1980 and transformed into a development community in 1992. SADCC and SADC emerged in the context of the struggle of the African people against apartheid and colonial exploitation, and draw inspiration from its liberation history as it builds a shared future.

The vision of SADC is one of a common future within a regional community where the people of Southern Africa enjoy economic well-being, improved standards of living, freedom and social justice, and peace and security. The mission of SADC is to promote sustainable and equitable economic growth and socio-economic development.

SADC can claim a number of impressive achievements. Politically, it worked towards the emancipation of Namibia and South Africa, and post-1994, revised its institutional and operational architectures. It expanded its membership from the original nine founders to the current 16-member states. It coordinates its activities with ICPs. Its affairs are run by a small Secretariat in Gaborone, Botswana. Priority projects include economic integration, development, peace and security, and democratic consolidation.7The SADC common agenda is pursued via the revised Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan and the revised Strategic Indicative Plan for the Organ and related policies, protocols, and strategies.

In general terms, SADC’s main challenges are intimately tied to the structure of the African economy: its ability to secure the well-being of its people as it simultaneously engages global markets and politics (including the emerging, high-tech, pre- and post-COVID-19 landscape). In reality, the typical African economy is characterised by a relatively small and well-resourced formal sector that operates in isolation from a large, growing and povertystricken informal economy and communal subsistence economy. This is the main structural challenge that SADC faces and from which many of its security threats emerge.

Even though SADC member states are integrated into the global economy, they export minerals and metals (mostly to Asian markets and the EU) and import much of what they need from the same external markets. Little trade happens inside Africa, although SADC member states do trade petroleum oils, agricultural products and electricity among themselves. Trade openness, technology transfer and capital investment positively influence manufacturing sector productivity growth in SADC countries. However, labour force and innovation factors influence growth in the SADC region negatively.8Douglas Chikabwi, Clainos Chidoko and Calvin Mudzingiri, ‘Manufacturing Sector Productivity Growth Drivers: Evidence from SADC Member States’, African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 9 no. 2 (2017), 163-171.

South Africa, in particular, provides the region with consumer goods and food. It has large trade surpluses with most SADC countries and its economic dominance has been a source of conflict in the region since it joined SADC. The relationship is therefore generally a competitive one which given the size, economic development and infrastructure deficits, can benefit more from collaboration.

Human development lags. The distribution of resources and income is highly skewed. More than 60% of the total regional population of 345 million lacks access to safe water, a third lives in abject poverty and about 40% of the labour force is unemployed or underemployed.9See Southern Africa Trust, Enhancing Citizens Participation in the SADC Development Agenda (Johannesburg: Southern Africa Trust, 2020) 9-12 https://knowledgehub.southernafricatrust.org/site/assets/files/1708/sadc_regional_integration_toolkit_for_non_state_actors.pdf

Extreme weather – a consequence of climate change – impacts directly on the region. Floods, cyclones and droughts are regular features of the Southern African landscape.10See David Lesolle, “SADC Policy Paper on Climate Change: Assessing the Policy Options for SADC Member States” (SADC Research and Policy Paper Series 01 Gaborone, 2012). https://www.sadc.int/files/9113/6724/7724/SADC_Policy_Paper_Climate_Change_EN_1.pdf

Under these conditions, the provision of good governance, stability and social justice are challenged. Indeed, the consequences of corruption and poor governance – which include armed conflict, organised and violent crime, resource exploitation, gender-based violence, erosion of democratic values and systems, and foreign political interference – thrive throughout many parts of the SADC region.

These are powerful reasons for enhanced regional coordination, if not integration, but weak external demand, the accompanying sharp fall in commodity prices, and the disruption in tourism that COVID-19 is causing will negatively affect economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa, and Southern Africa will not be spared.

South Africa’s moment

In the immediate context of the COVID-19 impact on Africa, several possibilities are emerging and are worth examining, if not by the SADC Secretariat, then by the regional leader: South Africa. South Africa has the distinction of being the continent’s most integrated country (well ahead of second-placed Kenya),11Africa Regional Integration Indexand is also the topmost performer on the productive and infrastructural dimensions. Moreover, it fares among the top four on the trade dimension and it is an average performer on the macroeconomic dimension. Its strength is in the productive dimension where it has the maximum score. Its weakness lies in the free movement of people.

What are the emerging opportunities?

A school of thought is emerging that offers a counter-perspective to the COVID-19 doomsayers. It suggests the crisis will prompt fundamental transformation in the African way of doing business and governing the public or common good. Distilled from several recent reports, below we present seven dynamic opportunities for such a re-think.12See: Kartik Jayaram, Kevin Leiby, Acha Leke, Amandla Ooko-Ombaka, and Ying Sunny Sun, ‘Reopening and Reimagining Africa’ McKinsey Africa Practice, 29 May 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/reopening-andreimagining-africa?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=e8b92edf091945a38de3fc87b6672ca4&hctky=1646885&hdpid=74e7e

7f1-8354-462d-b839-22bf4e734467#; World Bank, Assessing the Economic Impact of COVID-19 and Policy Responses in subSaharan Africa. (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020),https://olc.worldbank.org/content/africas-pulse-assessing-economic-impactcovid-19-and-policy-responses-sub-saharan-africa; The APRM, The Africa Governance Report; and the Africa Regional Integration IndexAlthough many of these seven opportunities are of continental value, they equally speak to Africa’s regional communities.

Reshape manufacturing, with a focus on self-reliance

The COVID-19 crisis has depressed demand and disrupted supply chains. But the crisis could also lead to a reshaped and more resilient African manufacturing sector provided that governments and businesses tackle long-standing barriers to industrialisation and cooperate to seize new opportunities such as the production of essential medical supplies and in the longer run, enhanced intra-African trade and supply-chains for export-oriented growth.

In pursuit of this objective, governments and private-sector partners need to focus on four priorities:

- accelerate implementation of the AfCFTA;

- improve ease of doing business across borders;

- coordinate industrial strategy and policy at the regional level; and

- explore new industries and product-space opportunities, such as agro-processing and pharmaceuticals.

Sustain momentum in regional and pan-African cooperation

Enhanced pan-African and regional cooperation must be built on these four priorities:

- Accelerate planned reform of pan-African institutions. The crisis is helping to clarify which institutions will be most relevant in forging Africa’s future. The AU’s African Governance Architecture and African Peace and Security Architecture in particular have grown in complexity over time and are in need of review.

- Strengthen regional institutions. Regional bodies can play a critically important role in the continent’s recovery. In addition to facilitating economic integration, they can serve as resources for member countries in creating and implementing coordinated development strategies, such as in human-capital development.

- Build closer relationships between the public, private, and development sectors. The crisis has helped to forge stronger relationships and new networks on the continent between governments, institutions, and private sector leaders.

- Speak with a more unified voice on the world stage. The crisis is creating political alignment around shared needs, for example: shaping debt-repayment terms and ensuring that donor funding is aligned with Africa’s priorities and needs.

Close the skills gap

The COVID-19 crisis is forcing educators to rethink curricula and pedagogy. The focus is turning to the benefits of the digital economy. The continent should therefore identify the skills gap and develop appropriate skills enhancement programmes. This speaks to Goal Four of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), namely ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning’.13The 17 SDGs form part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and are endorsed by the AU.Building on effective learning environments, cognitive skills, such as literacy, numeracy and problem solving, are required for any industry to be able to succeed in the global – and increasingly digital – economy.

A recent study of SADC countries’ readiness for the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) focused on the digital connectivity and skills components of the 4IR, given their role in creating an enabling environment for industrial development in emerging markets. The findings highlight priorities for the region, including policies and technologies to support affordable Internet service provision in rural areas, public sector capacitation and sensitisation, education and skills policy reform, and the creation of political and public buy-in for strong national visions of digital societies.14Chelsea Markowitz, “Harnessing the 4IR in SADC: Roles for Policymakers” (Occasional Paper 303, South African Institute for International Affairs (SAIIA), Johannesburg, October 2019), https://saiia.org.za/research/harnessing-the-4ir-in-sadc-roles-for-policymakers/.

Address infrastructure deficiencies

Policy-makers should immediately address the infrastructural deficiencies on the continent. Inadequate infrastructure hampers economic activities: raw materials do not get to the factories and production cannot happen; goods do not reach consumers; and trade and financial activities cannot flourish within or across borders. Foreign direct investment flows where there are locational cost advantages. As such, poor infrastructure is a deterrent.

Additionally, the functioning of modern society depends on the smooth supply of a vast range of infrastructural services that improve quality of life. These services ensure social wellbeing, health and safety standards and good environmental quality. Lack of infrastructure would negatively affect welfare.

Finance infrastructure

Long-term coordinated plans to develop and maintain basic infrastructures and logistics are necessary to sustain social and economic development and allow regional integration to happen. Policy should resort to innovative approaches to finance infrastructure. While the private sector is already involved in some countries, innovative variants of public-private partnerships (PPP) can be used to attract private capital and expertise. Although PPP critics decry their higher costs and issues of accountability, especially in Africa, there are many examples of successful projects which enhance infrastructure development.15Japan International Cooperation Agency and Southern African Development Community Development Finance Resource Center, Best Practices on PPP Infrastructure Development in SADC Countries, (Johannesburg: SAIIA, February 2020), https://www.jica.go.jp/botswana/english/office/topics/c8h0vm0000f9vzxu-att/200612_01.pdfPension funds and insurance markets can be envisaged as additional sources of finance for low-risk infrastructures.

Securing stable access to finance alone will not solve the problem of poor infrastructural integration. More competition should be introduced in procurement and operation and greater transparency should be established at all levels of the development of infrastructural projects. The regional legal and regulatory framework should be reviewed and improved accordingly.

Set up infrastructure management systems

It is important that governments learn how to assess and select an appropriate infrastructure delivery model at the early stages of a project preparation process and are fully aware of the implementation consequences in terms of the whole life-cycle cost.16For a discussion of Operations and Maintenance best practices, see: World Economic Forum, Strategic Infrastructure: Steps to Operate and Maintain Infrastructure Efficiently and Effectively, (April 2014), http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IU_StrategicInfrastructureSteps_Report_2014.pdf.In addition, governments need to develop a holistic and long-term strategy for operating and maintaining their physical assets that may represent a considerable financial burden for future taxpayers. More efficient infrastructure demand management systems therefore have to be set up, led by the SADC Secretariat in partnership with the private sector, in order to ensure the smooth supply of the infrastructure service or product, to better mitigate wear and tear and to cater for unforeseen events, such as natural or human-made disasters. Efficient management on a large scale can only happen if investment in new technologies is made and innovative management strategies are adopted.

Enhance integrated decision-making

In recognition of the complex, dynamic and often chaotic socio-political and economic environment, national and regional leaders must consider adopting more integrated ways of decision-making. They do not have the luxury of observing the world through single-issue lenses, whether security, development, democracy or economic growth. They have little choice but to coordinate their socio-economic and peace and security agendas. In fact, our African leaders must explore the advantages and disadvantages of creating a supranational organisation.

For now, the SADC Secretariat has an administrative and facilitative role pertaining to all SADC policies and areas of cooperation. SADC member states are mainly responsible for their direct implementation. This has resulted, for the most part, in low compliance between member states leading to generally higher transaction costs for both regional and international cooperation.

There are many benefits in delegating authority to a supranational organisation. These need to be pro-actively explained and demonstrated to participating member states and their citizens. First, there is the logic of integration and building a shared identity and vision. Second, if there is a synergy of economic and security concerns, a supranational organisation can become a more effective mechanism for crisis prevention and management. Third, the promotion of democratic governance and the realisation of the SDGs require highlevel coordination, cooperation and ultimately integrated decision-making at the level of a supranational organisation.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing untold hardship across the world and Africa is not being spared. COVID-19 also tests the basic assumptions upon which the liberal international order is built, including the return to the primacy of national interests at the expense of advancing regional goods. Africa has followed Western prescripts of regional integration and constructed an elaborate edifice but remains excessively dependent on the global political economy for its survival and growth. There is a real danger that countries will draw back behind their borders in the belief that it will shield them from the fallout of COVID-19. Yet, the disruptive pandemic offers dynamic opportunities for Southern Africa and the continent to reclaim agency.

To do this, we recommend that South Africa, as a prominent African and Global South voice, explores the regional and continental relevance of these seven opportunities. It should draw on its valuable experience of working with multiple partners at the levels of the AU and the UN. It should pursue these opportunities over the short- and medium-term with an inclusive set of regional partners: the SADC Troika and Secretariat, the region’s leading research institutions, civil society organisations, organised labour, the private sector, ICPs, and multilateral development agencies.

The South African president should extend his formidable negotiating skills to work with these partners in revitalising a post-COVID-19 social compact for Southern Africa as a foundational inspiration for Africa’s socio-economic and democratic recovery. Ultimately, strengthening African integration is indispensable for reaching the pan-African vision of a united, peaceful and prosperous continent, and the public and private sector leaders of South Africa, the SADC region, and the continent should aim for nothing less.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for this publication.

Professor Anthoni van Nieuwkerk has co-authored a chapter in the forthcoming edited volume on ‘Values, Interests and Power: South Africa’s foreign policy in uncertain times’, edited by Professor Daniel D Bradlow and Elizabeth Sidiropoulos and published by Pretoria University Law Press.