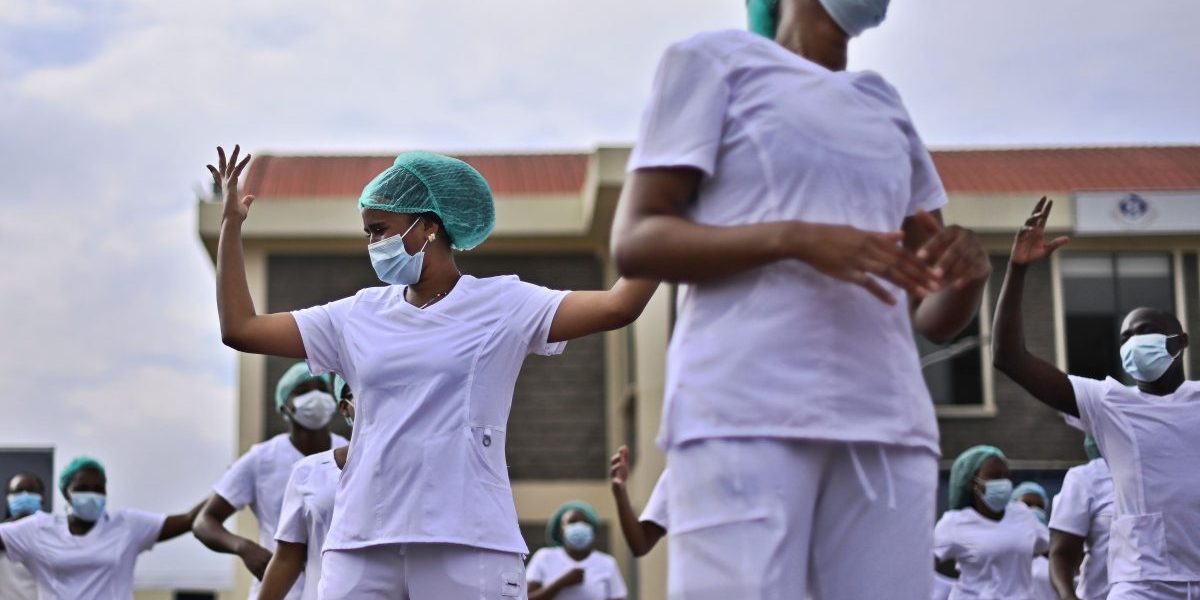

Five months into 2020, the picture that the WHO had in mind celebrating the work of nurses and midwives looks dramatically different. It’s one in which nurses and other critical medical personnel are being pushed to their very limits in a global pandemic that leaves more questions than answers in its wake. And yet celebrating their work is all the more relevant in the current context.

The challenges critical medical personnel are currently facing all lead back to a central question of care. There are three main challenges these critical workers face: insufficient supply of necessary protective equipment on a global scale; growing hostility towards them; and difficulties with access to childcare.

Considering the essential services they are providing, these are all challenges that they should not be subjected to, particularly not as the world marks the Year of the Nurse.

These critical workers all need the physical and emotional protection they deserve so that they fulfil their role as caregivers. It is imperative that their voices find expression and that their needs for personal care are met so that they extend care to the wider population in need of it.

Insufficient supply of necessary protective equipment

Critical medical personnel are some of the most important essential service providers the world needs right now. As a result, they are among the people with the most direct exposure to the coronavirus and in a perpetual state of risk. However, globally the life preserving Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) they need is in short supply. As the virus continues to spread, demand for this equipment naturally goes up. And with it, the cost of this necessary equipment has gone up significantly at the same time. As a response to the pandemic, the WHO calculates that medical personnel need a monthly total of 89 million masks, 76 million gloves, and 1.6 million protective goggles. Two months ago the WHO estimated that along with rising demand, a 40% increase in production of PPEs would be necessary.

Without the necessary protective equipment in the field, it is only a matter of time before a dilemma of a different kind develops: the more medical personnel infected with the disease, the less will be available to provide treatment to not only COVID-19 patients, but those with other conventional illnesses as well.

The effects of this can already be felt in South Africa. Duduza clinic in Gauteng has been closed after a nurse contracted COVID-19 and St. Augustine Hospital in Durban has halted the admission of new patients to allow staff and previously admitted patients to undergo testing following the death of three COVID-19 patients. These two examples show that society as a whole will be affected if nurses and other critical medical personnel are not thoroughly protected.

Growing hostility

Another challenge that nurses share on a global scale is increasing feelings of hostility towards them that often manifests in physical violence and aggression. Medical personnel have had to endure harmful chemicals and rocks thrown at them. In Mexico and Australia, hospital staff have refrained from publicly donning their uniforms for fear of physical violence and people spitting on them. In what Roborgh and Fast call ‘a deliberate weaponisation of COVID-19’, medical professionals in New Zealand and Australia as well as the UK have had to endure people trying to purposefully cough or spit on them.

In parts of Asia medical personnel have been threatened with arrest and in the UK and US have had to endure limitations on their freedom of speech for speaking out against uncooperative governments and the lived experiences of dealing first hand with the virus. In other cases, medical personnel are evicted from their homes by landlords concerned that they will carry and spread the virus (see also Roborgh & Fast, 2020). In Roborgh and Fast’s analysis, this adds ‘safety issues and economic hardship at a time of profound personal and professional pressure.’

Difficulties with access to childcare

A third important aspect to consider in this context is the question of childcare. Childcare, or familial care more broadly, is still largely dominated by women. This is important when considering the global gender – make up of medical workers, also dominated by women. The WHO has determined that women make up 70% of medical professionals worldwide. Zooming in on the country level, in the US, women occupy 76% of all jobs in the field and more specifically, they constitute 85% of nursing staff in the US.

Recently, it was reported that medical personnel in Japan are prohibited from sending their children to day care facilities or the few schools that are open, or in less extreme cases are required to present proof that their children are COVID-free. One hospital already reported that, as a result of the prohibition, medical personnel have had to take leave in order to tend to their children.

As part of the global response to the pandemic, schools and childcare facilities have closed en masse. Duty bound, medical personnel and other essential workers provide much needed services to the wider population. However one has to ask what happens in cases where these workers require childcare, but are unable to access it?

These three factors are all intrinsically linked to the one aspect that forms such a central part of the healthcare profession: care.

How can the world truly celebrate the Year of the Nurse when nurses and other critical workers are facing these challenges in the line of duty? Are those frontline workers who are providing an essential service really being honoured? It is necessary for the world to ask in the Year of the Nurse, ‘who will care for the caregivers?’