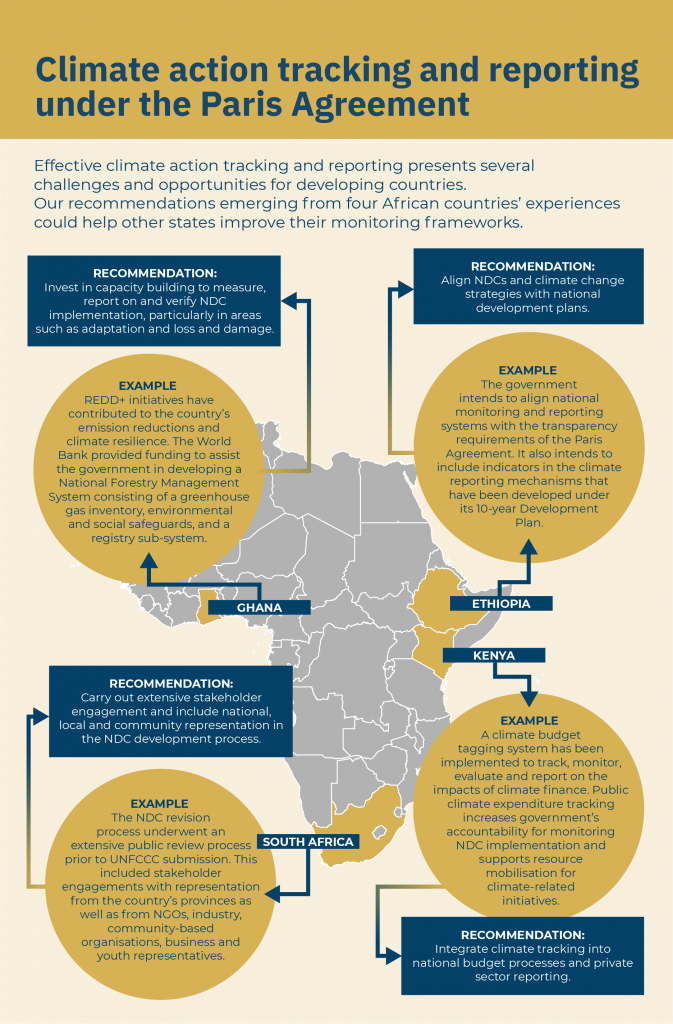

Recommendations

- Extensive stakeholder engagement and the inclusion of national, local and community representation in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) development process should be promoted to increase the level of accountability for NDC implementation.

- NDCs and climate change strategies should be aligned with national development plans in order to reduce the technical and financial resources required to track and report on NDC implementation.

- Climate tracking should be integrated into national budget processes and private sector reporting to help build robust datasets on climate action that informs NDC implementation.

- Capacity building to measure, report on and verify NDC implementation, particularly in areas such as adaptation and loss and damage, is essential for African countries to effectively track climate action.

Executive summary

At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 the Paris Rulebook was finalised. The rulebook provides practical guidance on implementing the Paris Agreement, which includes guidance on transparency and reporting on Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) through an Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF). NDCs communicate each country’s national commitments to climate change and are submitted to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) every five years. The ETF will ensure that countries report on their NDC implementation through the standardised submission and review of biennial transparency reports. With the final due date for the first such submissions set for 2024, NDC reporting and transparency are at the forefront of national and international climate action. This policy briefing seeks to explain the NDC reporting requirements of the ETF under the Paris Agreement, while identifying what challenges and opportunities this may present to the technical, institutional and financial capacities of developing countries. It is argued that enhanced transparency should ultimately facilitate ambitious NDC commitments, while aiding the development of more robust reporting mechanisms for climate action.

Introduction

Established under the UNFCCC in 2015, the Paris Agreement lays the foundation for a united, global response to climate change. NDCs are submitted to the UNFCCC every five years and are the primary communication tools through which countries provide details on their national climate change risks, as well as their mitigation and adaptation plans. Article 13 of the Paris Agreement established the ETF, with the purpose of providing common reporting requirements on NDC implementation, building on those previously established under the UNFCCC.1Yamide Dagnet et al., “Building Capacity for the Paris Agreement’s Enhanced Transparency Framework: What Can We Learn from Countries’ Experiences and UNFCCC Processes?” (Working Paper, World Resources Institute, Washington DC, 2019). The ETF sets out consistent reporting requirements to inform both on national progress toward implementing NDCs and on the status of the Paris Agreement’s long-term goal of reducing the global temperature rise to less than 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels. At COP24 in Katowice in 2018 the Paris Rulebook (then known as the Katowice Climate Package) was adopted, which details the modalities, procedures and guidelines for operationalising the ETF. It was decided that countries would be required to submit biennial transparency reports by no later than 31 December 2024. To allow these reports to be submitted by the 2024 deadline, operational guidance on reporting and review under the ETF needed to be completed. At COP26 this guidance was finalised through the adoption of:

- reporting tables and formats;

- outlines for the biennial transparency report and technical review report; and

- a training programme for the technical review experts.

Currently, countries are reporting on their NDC implementation through biennial reports (for developed countries) and biennial update reports (for developing countries), which are made publicly available by the UNFCCC. By 2024, it is envisaged that biennial transparency reports will replace these reporting mechanisms for both developed and developing countries. Transparency of reporting on NDC implementation will be further enhanced by a standardised review process of biennial transparency reports that will encourage mutual party learning and public engagement in climate action decision-making. While countries are mandated to submit NDCs every five years, the implementation thereof is legally non-binding. The ETF is thus meant to serve as an evidence-based tool to increase the transparency of NDC implementation.2Christina Voigt and Xiang Gao, “Accountability in the Paris Agreement: The Interplay between Transparency and Compliance”, Nordic Environmental Law Journal 1 (2020): 32. For political reasons, under the UNFCCC punitive action is not feasible for non-compliance on reporting requirements. However, the implementation of the ETF will ensure that no country will get a ‘free ride‘ in terms of the Paris Agreement. This is ensured by mandating countries to report on NDCs in relation to the ETF , while still allowing them the freedom to determine the content of their NDCs.

With the finalisation of the Paris Rulebook in 2021, transparency and accountability in NDC reporting have come to the forefront of national and international climate discussions. Not only will transparent reporting improve the collection of standardised, quality information across parties but it will also help to build trust and cooperation under the Paris Agreement. This commitment does, however, come with challenges for developing countries. The new reporting guidelines require more detailed reporting from developing countries than what was previously required.3UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, “COP26 Outcomes: Transparency and Reporting”, https://unfccc.int/process-andmeetings/the-paris-agreement/the-glasgow-climate-pact/cop26-outcomes-transparency-and-reporting#eq-4. Developing countries often lack the technical capacity for measurement, reporting and verification, including greenhouse gas accounting. These barriers, coupled with a lack of institutional and financial resources, will make it challenging for them to complete the standardised reporting templates that will be developed under the ETF. Several initiatives are now underway to help capacitate developing countries in this regard.

The UNFCCC Enhanced Transparency Framework

Biennial transparency reports

The ETF requires parties to comply with common reporting and review guidelines by 2024 through the submission of biennial transparency reports.4World Bank, “NDCs: Navigating Complex Data on Paris Commitments” (Brief, World Bank, Washington DDC, December 16, 2021). These reports will outline countries’ most up-to-date national efforts towards implementing their NDCs. Such efforts include national greenhouse gas inventories and evidence of financial, technological or capacity-building support provided by developed countries to developing countries. Additionally, parties are encouraged (but not mandated) to include information on national climate impacts and adaptation. Developing countries are also encouraged to report on the form of support needed (financial, technological or capacity building) to achieve their NDCs. The special circumstances of small island developing states and least developed countries are recognised, allowing them to submit relevant information at their discretion.

Technical Expert Review and the facilitative multilateral consideration of progress

Once submitted, biennial transparency reports will undergo an extensive two-stage review process. First, these reports (and greenhouse gas inventory reports) will be reviewed by an independent Technical Expert Review team. This team will be tasked with drafting a report to the UNFCCC outlining the extent of the country’s adherence to the ETF’s reporting requirements. The report will be non-punitive in nature and will include recommendations for both mandatory and non-mandatory NDC reporting.5Voigt and Gao, “Accountability in the Paris Agreement”, 43. The review report and biennial transparency report will then be assessed through a public-review process referred to as the Facilitative Multilateral Consideration of Progress, in which all countries must participate. During this process, countries will have to respond to written questions submitted by other countries regarding the outcomes of their biennial transparency report. The country under question will then present its national climate response activities, after which other countries will engage in a collective discussion, offering comments and recommendations regarding its adherence to the ETF. This working group discussion is open to registered observers.6Voigt and Gao, “Accountability in the Paris Agreement”, 44. All content produced during the Facilitative Multilateral Consideration of Progress will also be made publicly available on the UNFCCC’s website, further encouraging public engagement and enhanced transparency.

The Paris Agreement Implementation and Compliance Committee

Established under Article 15 of the Paris Agreement, the Implementation and Compliance Committee is responsible for oversight of country commitments to the ETF.7Voigt and Gao, “Accountability in the Paris Agreement”, 46. The committee consists of 12 members, with equitable regional representation from developed and developing countries. It is intended to support countries in identifying compliance challenges and share information on transparency and accountability best practice. Countries are encouraged to interact with the committee if they are struggling to report on the mandated requirements outlined in the biennial transparency report. While the committee’s actions are not punitive in nature, it may call on countries to engage should there be a direct violation of mandated reporting requirements under the Paris Agreement. To avoid duplication of effort, collaboration between the Technical Expert Review team (responsible for analysing the biennial transparency report) and the committee will be necessary in the cases where a party submits a report but fails to submit all necessary communications.8Voigt and Gao, “Accountability in the Paris Agreement”, 49. Measures taken by the committee will range from helping countries to engage with appropriate bodies for financial, technological and capacity-building support to recommending the development of an action plan for enhanced reporting compliance.9Voigt and Gao, “Accountability in the Paris Agreement”, 53.

Working toward the global stocktake

The ETF facilitates the operationalisation of the Paris Agreement by guiding countries on how to track, report and measure their NDC progress, as well as how to collect relevant information needed to inform the global stocktake. At COP24, it was decided that every five years, from 2023 onwards, a global stocktake would take place to inform the progress made towards meeting the long-term objectives of the Paris Agreement. Although the first global stocktake is set to start before the deadline for the first reporting submissions in 2024, it is important to note that, without the institutionalisation of the ETF, this stocktake would not be possible. Thus, while the ETF is a mechanism aimed at ensuring that countries continually report on their NDC implementation, it is also a valuable tool in the evaluation of global efforts toward reducing emissions.

What the ETF means for developing countries

To assist developing countries with the uptake of the ETF, several initiatives have been launched under the UNFCCC, as well as by multilateral development partners and private companies. For example, the Consultative Group of Experts has released a new technical handbook to help developing countries to prepare for the implementation of the ETF.10UNFCCC, “Understanding the Enhanced Transparency Framework: New Handbook Published”, July 10, 2020. The UNFCCC has also launched a Greenhouse Gas Help Desk to help them prepare for their national greenhouse gas inventories, as well as a measurement, reporting and verification/ transparency helpdesk. In addition, a Capacity-Building Initiative for Transparency is currently being supported by the Global Environment Facility to help strengthen the technical and institutional capacity of developing countries to implement the ETF.

Strengthening national measurement, reporting and verification systems

In Africa, strategic partnerships between governments and global institutions have resulted in more robust climate change reporting, which can feed into the ETF. For example, in Mozambique, the Initiative for Climate Transparency helped the government to establish a more robust measurement, reporting and verification system to align with the reporting requirements set out under the ETF.11Data 4 Better Climate Action, “Enhancing Climate Action in Mozambique”, November 2, 2021. In Ghana, REDD+12Reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks. initiatives have contributed significantly to the country’s emission reductions and climate resilience. To successfully report on this, the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility’s Carbon Fund provided funding to assist the government in developing a National Forestry Management System consisting of a greenhouse gas inventory, environmental and social safeguards, and a registry sub-system.13Data 4 Better Climate Action, “Establishing a Multi-Purpose National Forest Monitoring System to Improve Land Use Monitoring Capacities in Ghana”, November 2, 2021.

Linking local government reporting to national measurement, reporting and verification tools is also necessary to ensure coherent and accurate emissions reporting across sectors. In Serbia, a Climate Smart Information System for local government is being developed under the Capacity-Building Initiative for Transparency.14Global Environment Facility, The Capacity-Building Initiative for Transparency (CBIT) (Washington DC: GEF, October 2021). This system will be linked to the national measurement, reporting and verification system and feed into NDC reporting under the ETF. According to Ethiopia’s NDC, national monitoring and reporting systems will be aligned with the transparency requirements of the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, the government also intends to include indicators in the climate reporting mechanisms that have been developed under its 10-year Development Plan.15Abiyot Dagne Belay, Cynthia Elliott and Muluneh G Hedeto, “Ethiopia’s Updated NDC Underscores Its Focus on Climate Action”, World Resources Institute, July 26, 2021. In this way, the tracking of development goals is aligned directly with progress made on climate goals, feeding into an integrated and centralised system that allows for more efficient use of financial and technical resources.

Increased stakeholder participation

Stakeholder engagement and public participation in climate action facilitates the development of well-informed NDCs by increasing the accountability of countries to their NDC commitments. In South Africa, for example, the NDC revision process underwent an extensive public review process prior to its submission in 2021. This included stakeholder engagements with representation from the country’s nine provinces as well as from nongovernmental organisations, industry, community-based organisations, business and youth representatives.16Romy Chevallier, “Enhancing Nationally Determined Contributions Across the SADC Region” (Policy Briefing 253, South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburg, 2021). Such an extensive engagement process not only helps to integrate many different stakeholders’ needs and suggestions into NDC targets but also enhances ownership for its implementation and increases the incentive to ensure NDC reporting requirements are upheld.

It is also important that community and local knowledge on conservation and natural resource management is integrated into national climate plans and NDCs, as this often constitutes best practice for the local region. Involving communities in the design and implementation of climate interventions adds an additional layer of accountability. Local communities are held accountable for their involvement in implementing the NDC, and governments are held accountable by local communities for support and oversight. In Zambia, for example, community forestry management has been integrated into the forestry and REDD+ policy landscape.17A Bradley, G Mickels-Kokwe and K Moombe, “Scaling Up Community Participation in Forest Management through REDD+ in Zambia” (Policy Brief, Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, 2019). This transparency of actions should feed into national systems for measurement, reporting and verification on climate actions through the establishment of participatory measurement, reporting and verification systems at community level. Sharing of global and regional best practices on transparency reporting can also assist help developing countries with capacity building and training on measurement, reporting and verification techniques. This is especially important for the agriculture, forestry and land-use sectors, which often contribute significantly to developing country economies, have significant potential for mitigation and adaptation, and provide direct sources of income to many local communities.

Integrating transparency elements into national and private sector processes

To help facilitate the collation of information to feed into NDC reporting requirements, it is important that national and private sector processes incorporate transparency elements. For example, one of the non-mandatory requirements for developing countries under the ETF is to report on any support needed to successfully implement its NDC. Integrating ‘climate budget tagging’ into national budget processes or undertaking a climate public expenditure and institutional review18A Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review is a diagnostic tool to assess opportunities and constraints for integrating climate change concerns within the national and sub-national budget allocation and expenditure process. See UN Development Programme, A Methodological Guidebook: Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review (CEIR) (Bangkok: UNDP, 2015). could show governments how much is being spent on climate-related activities, what these activities are, and where gaps currently lie regarding meeting the objectives of the NDC. These processes can also help governments to understand how much climate finance is being provided by donor funding, and how much comes from national budget allocations. It also aids with collaboration on climate change issues across ministries, involving key stakeholders from ministries of finance, environment and related sectors at both a national and a local level. In Kenya for example, a climate budget-tagging system has been implemented to track, monitor, evaluate and report on the applications and impacts of climate finance. The National Climate Finance Policy provides the institutional framework to guide the implementation of tracking both mitigation and adaptation expenditure through a budget coding system. This enabled the government to accurately report that national spending on climate change increased from $776 million in the 2019/2020 financial year to $957 million in the 2020/2021 financial year.19The Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative (CABRI), Inclusive Budgeting and Financing for Climate Change in Africa (South Africa: CABRI, 2021) In Bangladesh, a Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review in 2012 showed that about three-quarters of all national spending on climate adaptation came directly from the national government, and that poor households’ spending on adaptation often exceeds their income.20UNDP Environment Programme, Aligning Climate Finance to the Effective Implementation of NDCs and to LTSs: Input Document for the G20 Climate Sustainability Working Group (Argentina: UNEP, 2018). These findings assisted the government in increasing its negotiating power for stronger international support for climate change.

To develop robust biennial transparency reports that consider all national emissions and reductions, it is vital that the private sector is properly accounted for. Governments should ensure that the private sector is both incentivised to comply with voluntary and/ or mandated reporting and motivated to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. This may require additional legislative developments in the form of certification schemes, carbon taxes or emission-trading schemes. However, simply raising the private sector’s awareness of climate change issues, as well as and the objectives of the NDC could result in increased uptake of greenhouse gas measurement, reporting and verification within the private sector.

Conclusion

The finalisation of the Paris Rulebook at COP26 was a major milestone in the implementation of the Paris Agreement. The 2024 due date for the first submission of reporting requirements under the ETF has encouraged countries to increase their transparency and accountability for NDC implementation, monitoring and evaluation. This transparency framework will mandate all countries to report on actions related to the achievement of their NDC, and compel them to engage with one another in collective dialogue on national and global efforts towards meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. The ETF has also increased governments’ responsibility to ensure that their national systems for measurement, reporting and verification are robust, that all relevant stakeholders are accounted for in NDC negotiation processes, and that relevant ministries and departments collaborate to share information that will feed into a collective reporting mechanism on NDC implementation.

Given the institutional, technical and financial constraints faced by developing countries, there is an urgent need for regular training and capacity building on NDC reporting. This is currently an important topic in international climate discussions and will be key in informing the outcomes of COP27 taking place in Egypt in 2022. This will be crucial for Africa, both in enhancing national GHG inventories and in highlighting the importance of climate action reporting on adaptation, loss and damage, which was a key outcome for climate finance support at COP26. While robust frameworks have been developed to account for mitigation activities, there is still a need for increased knowledge dissemination on how to collect data accurately and account for adaptation. Information collected through the ETF should contribute to this, while creating a shared global accountability mechanism for NDC implementation and incentivising more ambitious NDC commitments.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of SIDA for this publication.