Virtually all 55 African countries have confirmed cases. These numbers are set to skyrocket as under-resourced public health systems grapple with containing the pandemic.

The World Health Organisation’s Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, former health minister of Ethiopia, has implored Africa to wake up to the threat , and noted how the continent is least equipped on its own to combat the pandemic.

African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) Country Review Reports (CRRs) from Sierra Leone, Lesotho and Tanzania illustrate how problems in the health sector, coupled with poor governance and corruption, can exacerbate outbreaks like the coronavirus and Ebola.

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone was peer reviewed in 2012. This was before the devastating Ebola outbreak in 2014 that caused 3,955 deaths in the West African country.

Sierra Leone’s civil war from 1991 to 2002 damaged the quality of health service delivery and the sector became chronically under-funded as a result. Despite government efforts its CRR said, “health service delivery, particularly to the poor and to rural areas, continues to suffer from (i) limited access due to distance and cost of services; (ii) inadequate transport and referral system; (iii) inadequate supply of medicines and supplies; (iv) limited community participation in sanitation and healthcare; and (v) critical shortage of health professionals.”

The CRR reported that a “shortage of clean water and poor sanitation are the major factors contributing to the poor health situation”. A 2010 National Public Perception Survey on Corruption listed the Ministry of Health and Sanitation as the most corrupt ministry in the country. The CRR asserts that challenges in the health sectors “are exacerbated by corruption and the continued theft of medical supplies from government health facilities”.

Lesotho

In Lesotho – peer reviewed in 2010 – the CRR reported that primary healthcare is available for free at all government clinics. Access to healthcare nonetheless remains problematic for many. Approximately 38 percent of the population need to travel for over an hour to reach the nearest facility. In the rural mountainous areas this increases to 78 percent of inhabitants. Commendably, Lesotho utilises a ‘flying doctor service’, of providing medical services, including ambulance by air to remote areas as part of its health system.

In spite of these efforts, a survey conducted during the APRM review showed that the population generally feels the government does not deliver effective health services. Poverty, experienced by large segments of the population, further erodes the ability of citizens to access health services. The health information system in Lesotho is furthermore reported to be weak, partially due to parallel collection of health statistics from various sources. There are additional challenges in the numbers of qualified medical staff, as well as drugs and other medical supplies. The lack of personnel in particular makes it difficult to provide adequate basic services. This situation is further exacerbated by the brain drain to South Africa, where salaries are much higher.

Tanzania

Tanzania was peer reviewed in 2013. Its CRR said, “While Government has attempted to restore free health services, not only is access still a challenge but the situation is aggravated by high costs and poor health services. There are also medical staff shortages, inadequate facilities, and a lack of medicine in rural areas especially.” Health reforms are overly dependent on donor funding, the report added.

It was also noted that “Drawbacks preventing citizens from enjoying their health rights are: inaccessible health facilities which are also unequally distributed; a lack of clearly-defined free care delivery strategies to bring medical care to special groups such as pregnant women, children under five, and elderly persons; the shortage and lack of qualified health workers; increasing incidence of … cancer, strokes, diabetes, and tuberculosis; and, poor service delivery.”

Tanzania’s Country Self-Assessment Report (which feeds into the CRR) identified key challenges, “including the fact that even the most basic equipment for emergency obstetric procedures in health centres are missing; there is a lack of ambulances and serious shortages in skilled birth attendants”. There are hidden costs to “free healthcare”, including transport, bribes and equipment.

Has the ability to deal with the current pandemic improved since the reviews?

These reports were done several years ago. Africa grapples with unreliable or indeed unavailable statistics, which is also bedevilling accurate monitoring of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Many African states lack the statistical infrastructure to gather accurate data. More accurate data is vital to make a true assessment of health needs, monitor progress and foster greater accountability.

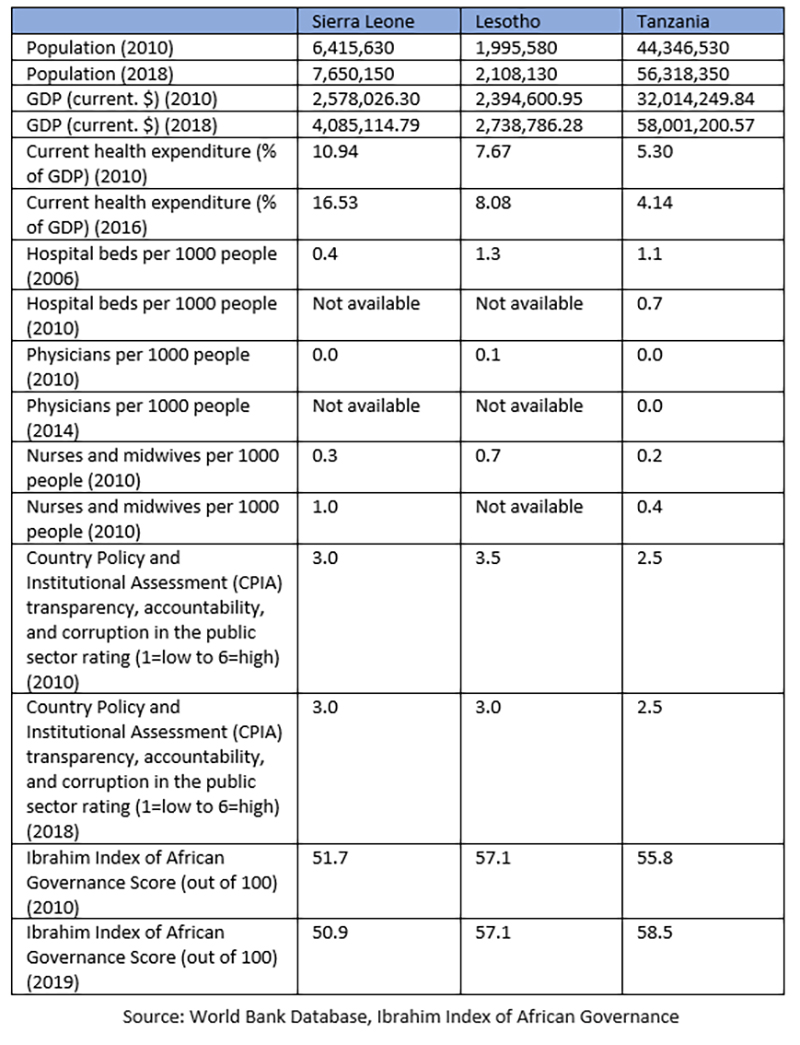

Updated figures from the World Bank (including World Health Organisation figures) show that there has not been much improvement in these states since the APRM reviews were conducted.

The statistics on the numbers of health professionals are extremely worrying: these states are not in a position to monitor improvements or mount an effective response in the event of a crisis.

Ebola lessons for COVID-19

Of the three countries discussed, Sierra Leone had one case, Lesotho had no confirmed coronavirus cases, and Tanzania had 13 at the time of writing. But the weaknesses diagnosed by the APRM suggest that the virus will be extremely damaging in these brittle health environments. The high prevalence of tuberculosis, malaria and/or HIV/AIDS also makes these states particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.

It’s worth remembering what was said by the deputy chief of staff for former Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, W Gyude Moore , “It starts off as a health crisis, but it is always going to become a governance crisis”. Liberia was hard-hit by the Ebola outbreak in 2014.

Other lessons from the Ebola crisis he mentions: ensure links between national government and lower levels work; trust in the government is vital and use credible figures to convey key health messages; invest in testing, even with limited resources; establish specialised health facilities for virus sufferers; isolation is the top priority to break the transmission chain, and enforce social distancing.

When discussing lessons from the Ebola outbreaks for COVID-19, Sorcha O’Callaghan of the London-based global think tank, the Overseas Development Institute, wrote:

“The spread of a dangerous disease requires a broad response that goes beyond medical provision. Treating Ebola predominantly as a health crisis meant that the surge capacity and emergency funding characteristic of a large-scale humanitarian crisis were not triggered. Wider implications – for instance for food security, livelihoods and education – were neglected, and NGOs were unclear on how or where to engage. A narrow focus on Ebola also downplayed other health implications, and people with other conditions were left without treatment due to the outbreak.”

These messages sound very familiar in the context of the current outbreak of COVID-19. The question is whether countries and their citizens will heed them with the urgency that is needed.