The final tally gave Bongo 41.7 percent of the vote, with the main contenders, Andre Mba Obame and Pierre Mambounda receiving 25.8 and 25.2 percent respectively. But in the country, this verdict has been met with protests in the streets of the capital, Libreville, and clashes with police in other towns as opposition supporters question the outcome.

The series of post-election events in this small oil-rich country follow a worrying pattern that is becoming commonplace in African politics. These point to serious weaknesses in democratic culture and institutions, and threaten both the prospects of democratic consolidation and the achievement of genuine development. The pattern includes, with varying degrees of severity, weak and disunited opposition based on personality or tribal politics; domination of national politics by a single party, accompanied by arrogance, incompetence and corruption; emerging presidential dynasties (or efforts to establish them); refusal of losing parties and candidates to accept electoral results; and post-election protests that threaten national political stability as they turn violent, pitting the state against citizens.

The recent election in Gabon followed the death of long-time President Omar Bongo, who had led the country for more than forty years, having come to power in 1967. Although the country is one of a few in Africa which escaped military coups d’etat, the stability that Gabon endured was bought at the cost of one-party dictatorship and ruthless suppression of opposition. External support (principally from France, the former colonial metropole) and revenue from the country’s rich oil resources were central to economic growth and to the elder Bongo’s hold on power.

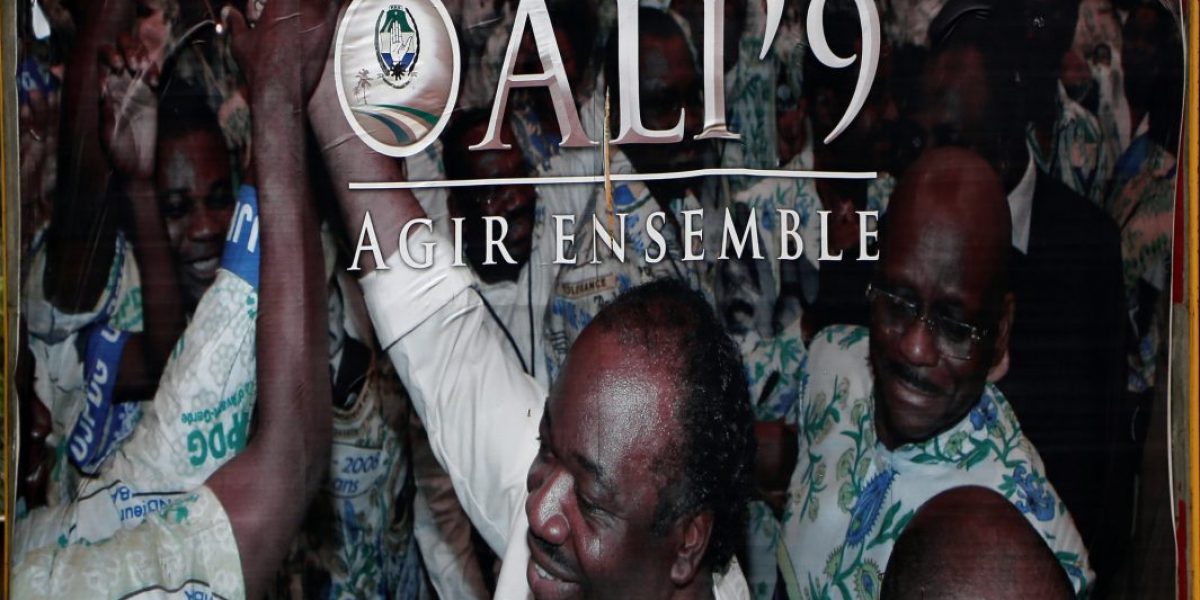

In this election, the younger Bongo was originally pitted against no less than 20 rivals –although in the end a total of 17 candidates contested the poll. Given the history of his father’s dominance and the fractious nature of opposition politics in that country, Ali-Ben Bongo was virtually guaranteed victory. Of course, his ability to mobilise the vast resources available to him was also a factor. The failure of opposition to unite behind a single candidate, and the disarray in their ranks was one of the main characteristics of the campaign. They lacked coherent policy programme alternatives compared to the ruling party. This in the end does not offer the voter a choice, and weakens democracy. But more important, the real reason is often the hunger for power on the part of politicians, resulting in many of them resigning from the ruling party to form their own after they fail to be elected to office.

The examples of runner-up Jean Eyeghe Ndong, who resolved to run as an independent against Bongo after failing to win nomination of the ruling party as presidential candidate; and of the Congress of the People (COPE) in South Africa, formed after the failure of one faction to win positions in the ruling African National Congress’ (ANC) senior councils, make this point. Of course, these politicians will vehemently deny this view, but the often similar policy platforms they propose with the party they have left clearly demonstrate that their disagreements rests in office-seeking, not issues. There is also a pattern of splintering within opposition parties themselves, thus further reducing their chances of successfully challenging the ruling party, as was the case with the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) in Zimbabwe before the 2008 poll. Again, personality politics were at the forefront of this development.

Gabon’s ruling party has its roots in the struggle for independence, and has dominated national politics since then. In Southern Africa in particular, former liberation movements continue to dominate national politics (whether this liberation was from colonialism, the military or discredited ruling parties that stayed in power too long). In Zimbabwe, Namibia, South Africa, Angola and Mozambique, for example, the hold of ruling parties on power is based in part on their legacy as liberators. This has been accompanied with arrogance of power, characterised by allegations of corruption, incompetence and an attitude of entitlement to rule. Combined with the absence of a credible opposition that could displace them, many of these parties have tended to treat state and party as inseparable –in an era where one-party government has been banished formally. Gabon seems to be following and entrenching this pattern.

African elections from Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Madagascar, and Kenya to Gabon and elsewhere have also seen a pattern of contested electoral results, amidst allegations of irregularities and outright rigging. In varying degrees, this destabilises governance and often calls into question the legitimacy of governments emerging from such polls. The instability that results from these disputes ranges from relatively mild and issue-specific (as with the final allocation of parliamentary seats following the 2007 election in Lesotho), to severe and catastrophic (as in the Kenyan and Zimbabwean cases in late 2007 and early 2008 respectively). The effects on society and the economy can seriously retard development, rendering countries and regions vulnerable to reversal of the gains made since re-democratisation began in the late 1980s. Gabon’s impressive stability and economic growth (with annual Gross Domestic Product growth averaging over 3 percent since 2002, and above 4 percent for 2008) seems threatened by this possibility if that country’s politicians do not look beyond their short-term interests. The prospect that oil revenues will decline as the country’s reserves are exhausted in the next twenty years makes the challenge even more urgent.

Into this mixture also has been thrown an emergent pattern of presidential dynasty-building. Together with Foure Eyadema in Togo, Joseph Kabila in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Ian Khama in Botswana, Ali-Ben Bongo has joined the ranks of presidents whose fathers occupied State House before them. While not necessarily negative by itself (the Kennedy and Bush political dynasties of the United States, the Bhutto family in Pakistan, and India’s Ghandi-Nehru family dynasties come to mind), the contestation that has surrounded efforts at passing the presidency from father to son should sound a note of caution. Of course, there are variations in the circumstances under which this hand-over of power from father to son happens (for, example, there was a more than 20-year gap between the current Botswana president and his father, with the baton being passed along a line of legitimately elected before reaching the younger Khama).

The difficulty with the latter pattern, which is also ostensibly being contemplated in other parts of the continent (in Senegal by Abdoulaye Wade, in Libya by Muammar Gadaffi and in Egypt by Hosni Mubarak where heirs-apparent are being groomed for the top job) is the limitation it places on political choice. The younger Eyademas, Kabilas and Bongos are seen as being imposed. While political grooming within families is a common strategy the world over, the subjective view that these “sons-of-the-leader” carry an inordinate advantage over their rivals should not be taken lightly. The degree to which Ali-Ben attends to the problems of economic diversification, combating corruption and redistributing the country’s considerable wealth, will determine whether the Gabonese will accept the Bongo “succession”.

On their own, the trends identified above are already significant obstacles in the way of consolidating Africa’s democratic gains of the last decade. In a country rich with natural resources and poor in both democratic culture and economic equality like Gabon, they can be explosive. Developments in Kenya following the disputed election of December 2007 should be a warning to the Gabonese, and to Africa’s continental governance architecture, to be proactive in addressing these challenges. How things turn out in Gabon is thus of significance for Africa. For a continent seeking to reaffirm its place in the world, and battered by the current economic recession, complacence in the face of these clearly identifiable threats is not an option.