For decades, the term ‘Giant of Africa’ has been synonymous with Nigeria. With a population estimated at over 237 million people, at one point the continent’s largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in nominal terms, vast oil reserves and a legacy of regional leadership, Nigeria has long been seen as the leader of Africa. From forming the backbone of peacekeeping operations in Liberia and Sierra Leone, to spearheading the creation of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) 50 years ago and influencing continental diplomacy, Nigeria projected itself as a powerful state at the epicentre of post-colonial Africa.

Yet the 21st century has quietly disrupted Nigeria’s outright dominance. Post-apartheid South Africa – less populous, seemingly less economically troubled, and geographically remote from Africa’s traditional power fulcrum – has emerged as a powerful co-claimant to, or even usurper of, the continental leadership mantle. Its active role in global forums such as the Group of 20 (G20) and BRICS (now comprised of Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates); its energetic presence at the United Nation and its controversial legal confrontation with Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since 2023 on charges of genocide in Gaza, all demonstrate a state that has overcome significant domestic impediments to be taken as an important international player. As the sole African country in the G20 (having successfully lobbied for the African Union (AU) to get a permanent seat), hosting the G20 summit in November 2025 is a strong symbol of South Africa’s influence and its representation of the global South.

Can South Africa now be considered as Africa’s ‘other giant’? Or has it eclipsed Nigeria entirely? And does it matter who the giants are, anyway?

Demographic and Economic Muscle

Nigeria’s claim to continental hegemony rests on its population size. Currently estimated at 237 million, Nigeria’s population is projected to reach 400 million by 2050, which would make it the third largest country in the World by population, trailing just behind India and China. There is a twin ‘demographic dividend’ underpinning Nigeria’s populous soft power – a large consumer market and extensive labour capacity. It is simply too big to be ignored.

Economically, in April 2014, due to a rebasing of its GDP, Nigeria became Africa’s largest economy, with a nominal GDP of $574 billion. Nigeria is Africa’s top oil producer, with the tenth largest proven oil reserves in the world. Oil revenues dominate Nigerian export revenues to the tune of over 90%. This gives the West African behemoth considerable heft within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Its resource power remains considerable, even with oil price volatility and underinvestment in the industry.

Military Strength and Peacekeeping Legacy

Military power also underpins Nigeria’s claim to gianthood. From the 1970s, Nigeria projected its leadership as a strong supporter of decolonisation and the anti-apartheid activities of African states (and colonies). In the 1990s and early 2000s, Nigeria drove the regional stabilisation missions in Liberia and Sierra Leone. It supplied thousands of troops to the ECOWAS Monitoring Group. Much later, Abuja was also instrumental in forcing The Gambia’s Yahya Jammeh from power in 2017, threatening ECOWAS military action. This entrenched Nigeria as a security provider in West Africa, bolstered by being ECOWAS’s host country and biggest funder, and a strong proponent of regional economic and political integration. Bold leadership from Abuja helped to bring peace and the country’s moral reputation was boosted by its willingness to put boots on the ground and bear sacrifices.

But diplomatic power does not rest on size, funds and military might alone. Internal factors such as government, statecraft and leadership count, too, and Nigeria’s performance in these areas has fallen short. Nigeria faces serious internal security problems, and has become more volatile and violent. Its willingness and ability to project hard power in West Africa has diminished. The Sahel’s security has deteriorated since the Arab Spring of 2011, and Nigeria has not featured prominently in efforts to combat Islamist extremism and the string of coups in the region. At home, Abuja is dealing with simultaneous security crises – the Boko Haram insurgency and the Islamic State West Africa Province – in the North East, banditry and runaway insecurity in the North West and long-running secessionist threats in the Niger Delta and South East. These problems have made external deployments politically costly and less feasible.

Pan-Africanism and the Vision of African Leadership

In the 1970s, Nigerian leaders articulated that ‘Africa is the centrepiece’ of Nigeria’s foreign policy, and this view has dominated the country’s diplomacy ever since. Nigeria consistently positioned itself in support of Africa’s decolonisation and liberation movements. It was a founding member of the Organization of African Unity in May 1963 and later the AU, formed in 2002. Nigerian cities hosted important African summits and Nigeria supported AU organs financially. President Olusegun Obasanjo – along with former South African President Thabo Mbeki and others – was key in the establishment of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development in 2001 and the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), the continent’s good governance assessment and promotion instrument, in 2003. Nigeria and South Africa have both undergone two APRM reviews. In global forums, Nigeria presented itself as the default African spokesperson.

However, with weak leaders since Obasanjo and many internal issues, Nigeria’s international presence has diminished. The country has become more cautious and reactive. As domestic governance challenges grew – corruption, instability and electoral legitimacy concerns – its appetite and capacity for global leadership diminished.

The Quiet Rise of South Africa: Setting The Stage For A Rival Giant

Nigeria was widely seen as the uncontested post-independence African hegemon from the 1960s. South Africa entered the continental arena late. Apartheid policies had isolated and ostracised South Africa from the continent from 1948 until the dawn of democracy in 1994. But once liberated, South Africa lost no time in redefining its role – not only as a regional power in Southern Africa, but as an advocate for Africa’s place in the world in global institutions, championing the global South’s key cross-border issues like climate change, disease control and migration.

Despite its much smaller population (of approximately 67 million), South Africa positioned itself as a diplomatic equal to Nigeria through multilateral engagements. Its global visibility rose through hosting international summits and events (e.g. the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, the 2003 Cricket World Cup and the 2010 FIFA World Cup). It also became the sole African member of the G20 in 1999. South Africa’s G20 membership elevated its visibility beyond continental politics. While Nigeria’s focus remained regional, South Africa began shaping global economic policy. Pretoria has consistently used the G20 platform to advocate for development finance, fairer global trade and climate justice. Hosting the 2025 G20 Summit in November is a watershed moment in South African diplomacy.

South Africa joined the BRICS in 2010 as the sole African member (until Egypt and Ethiopia joined in 2024). This accession represented a symbolic pivot toward South-South cooperation. Though its economy was smaller than Nigeria’s at the time, South Africa was chosen because of its international profile, institutional maturity and geopolitical positioning. The creation of the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) in 2015 and South Africa’s active role in shaping its operations cemented its influence within the bloc. Johannesburg even offered to host the NDB but it lost out to Shanghai. In contrast, Nigeria only joined BRICS as a ‘partner country’ in 2024 – a lower-tier involvement. This step forward nevertheless illustrates how much ground Abuja must cover to match Pretoria’s embeddedness in global decision-making structures.

After 1994, South Africa’s ‘rainbow nation’ was seen as an example of peaceful ethnic diversity and the world was invested in the South African ‘miracle’. South Africa cultivated high-level bilateral ties with the US, the EU, Britain, China, India and Russia, among many others. Hosting 123 embassies and high commissions and 53 consulates, Pretoria houses the most diplomatic missions after Washington, DC.

South Africa also cultivated a strategic narrative rooted in values: human rights, multilateralism and international law. This post-apartheid moral identity – especially under Nelson Mandela between 1994-1999 and Thabo Mbeki between 1999-2008 – enhanced South Africa’s soft power. Pretoria’s emphasis on diplomacy over militarism contrasted with Nigeria’s traditional reliance on regional security projection. By the 2010s, South Africa had blossomed on the international stage. Its diplomacy brought peace (of sorts) to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi and Sudan.

Some, like analyst Gustavo de Carvalho, have interpreted South Africa’s case against Israel at the ICJ as a measure of the country’s global standing and confidence and its willingness to use international law, despite severe pressure from Western countries to drop the case. Others, like businessman Ivor Ichikovitz, have criticised Pretoria’s seeming hypocrisy, contrasting its rock-solid support for the Palestinians with its apparent indifference towards Ukraine (although it has become more even-handed over time). Iran has been accused of bankrolling and encouraging the ICJ case, for example, by analyst Frans Cronje. Nigeria, by contrast, was notably silent on this case. While it issued general statements of concern about the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, it neither condemned nor supported South Africa’s legal challenge. For some, this reflected Abuja’s desire to maintain a cautious foreign policy posture, given its strong military ties with Israel and the US. But it also revealed a deeper issue: Nigeria lacks the legal infrastructure and foreign policy assertiveness to project itself as South Africa has done.

In the Russia–Ukraine war, since 2022, South Africa has claimed it is non-aligned. Many critics saw it clearly leaning towards Russia in the initial stages, when it blamed expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization for the conflict, participated in naval exercises with Moscow and Beijing, and sent several prominent delegations to Russia. However, this was balanced out in its participation in the African Peace Initiative in 2023, in which seven African countries (Comoros, Congo-Brazzaville, Egypt, Senegal, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia) visited both Kyiv and St Petersburg. Notably, Nigeria was not included. In April 2025, Cyril Ramaphosa hosted Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, in South Africa, where support for a just peace deal was emphasised. In contrast, Nigeria has played no role in efforts to end this war.

There are several reasons Nigeria has not capitalised on similar opportunities for international elevation. Persistent insecurity, widespread corruption, and a slow-moving bureaucracy have inhibited Nigeria’s foreign policy agility. While South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation has been relatively well-resourced and proactive, Nigeria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has often suffered from underfunding and strategic drift. Nigeria’s economy remains heavily reliant on crude oil, at almost 69% of its exports, with limited diversification. This has exposed it to boom-and-bust cycles that have eroded development planning and hindered long-term investments in diplomatic or multilateral strategies. South Africa has a more diverse industrial and services base, giving it greater institutional depth.

Successive Nigerian governments have failed to articulate a clear, consistent global vision. While ‘Africa as the centrepiece’ remains a slogan, it is rarely translated into strategic policy. South Africa’s post-apartheid governments, particularly under Mbeki and Ramaphosa, have woven foreign policy into domestic identity and global ambition – using diplomacy for national branding. Ramaphosa has emphasised that foreign investment is needed to tackle the ‘triple challenge’ of poverty, inequality and unemployment.

South Africa benefits from a globally respected and vibrant civil society, legal community and media environment. Its universities, think tanks, and NGOs frequently partner with international institutions. It has large companies dominating the African markets, including in Nigeria, in the communications, retail and financial services sectors. Nigeria’s soft power is more cultural (including Nollywood and Afrobeats) than institutional. It has yet to cultivate international policy think tanks or legal institutions with a global impact like South Africa has.

South Africa’s Balancing Act: Risks and Limitations

South Africa has vulnerabilities, despite its impressive diplomatic ascent. Internally, it faces high unemployment, energy crises, and persistent inequality. Externally, its alignments sometimes attract Western criticism – including its stance on Russia, China, Iran and Israel. Moreover, leading from the global South can be isolating. While Pretoria’s ICJ move won it plaudits, it also faced severe diplomatic pushback, including threats to trade and investment. The true test will be whether South Africa can convert symbolic leadership into tangible benefits for Africa – climate finance, equitable trade reform, debt restructuring – without alienating powerful partners.

South Africa’s diplomatic rise is not just a story of its capabilities – it also reflects spaces left vacant by Nigeria. Through active, strategic engagement with global institutions, legal diplomacy and value-driven foreign policy, South Africa positioned itself as Africa’s global voice. Nigeria, though still powerful, appears reactive and more comfortable with regional influence than shaping international norms.

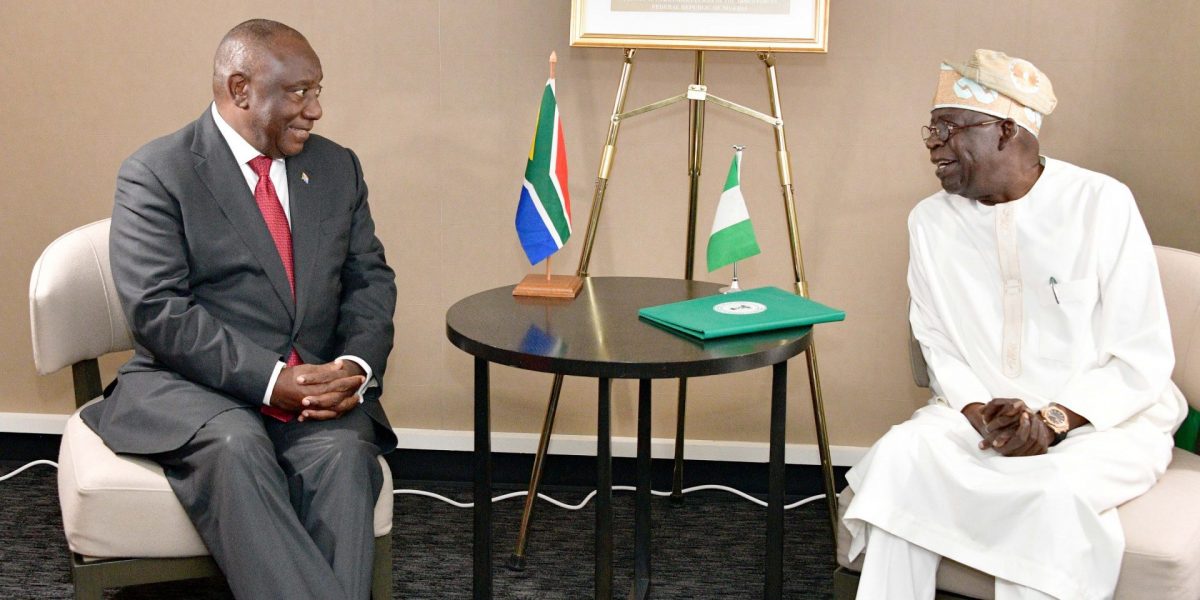

In 2025, with South Africa hosting the G20 and Nigeria edging closer to BRICS integration as a partner country, the African landscape needs a new balance. Whether the Abuja-Pretoria dynamic becomes a productive partnership or a competitive rivalry will depend on how each country interprets its role – and how receptive the rest of the continent is.

Despite the obvious chemistry and personal rapport between Obasanjo and Mbeki, tensions have surfaced in the South Africa-Nigeria relationship. One of the most significant was President Nelson Mandela’s roasting of General Sani Abacha when Ken Saro–Wiwa and 8 other Ogonis were killed in 1995. Mandela’s attempt to ban Nigeria from the Commonwealth ultimately backfired, and taught Mandela a lesson – never criticise fellow African leaders publicly. Nigeria boycotted the African Cup of Nations held in South Africa in 1996. The countries have tried to one-up each other ever since. Xenophobic attacks on Nigerians in South Africa have created backlash against South African companies in Nigeria. There have been frequent spats over visa issues in the past.

This article was first published in The Republic.