Summary

- Although Africa contributes only 3.8% of global greenhouse gas emissions and bears the brunt of climate impacts, several countries in the region have submitted ambitious targets in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to help reduce global emissions.

- Many African countries face debt challenges, have limited fiscal space to fund their NDCs and must depend on external climate financing.

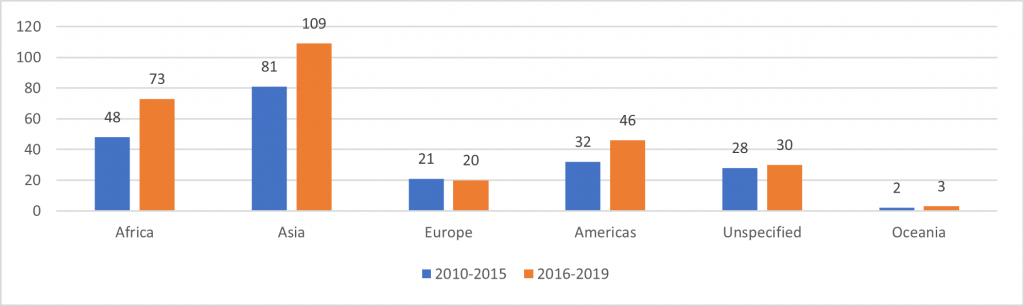

- Despite being the continent most affected by climate change, Africa has received the least amount of climate finance flows. For example, from 2010 to 2015, $212 billion worth of climate finance was disbursed, with $81 billion (48%) going to Asia and $48 billion (23%) going to Africa.

- Inaction on climate finance is worsening living standards on the continent. Africa loses $7–$15 billion annually owing to climate change, and this is expected to rise to $50 billion by 2040.

- To help accelerate a just energy transition in Africa, the Brazilian and South African G20 presidencies, with the support of the AU, should focus on ways to increase not only the flow of climate finance to the continent but also the quality of that finance.

- This includes providing more below-market interest rate loans or concessional capital to African and other emerging developing economies and implementing innovative financing mechanisms such as debt-for-nature swaps.

Executive Summary

Although Africa contributes only 3.8% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and bears the brunt of climate impacts, several countries in the region have submitted ambitious targets in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to help reduce global emissions. Many African countries face debt challenges and have limited fiscal space to fund their NDCs, and thus must depend on external climate financing. Despite being the continent most affected by climate change, Africa has received the least amount of climate finance flows. Inaction on climate finance is worsening living standards on the continent. This policy insight examines the Indonesian and Indian G20 presidencies and assesses how they addressed Africa’s priorities and concerns regarding a just energy transition and mobilising sufficient climate finance towards this goal. It then proceeds to address issues that should constitute the African agenda under the upcoming Brazilian and South African G20 presidencies.

Introduction

This paper examines the Indonesian and Indian G20 presidencies and assesses how they have addressed Africa’s priorities and concerns regarding a just energy transition and mobilising sufficient climate finance towards this goal. It also addresses the issues that should constitute the African agenda under the upcoming Brazilian and South African G20 presidencies. Given the influence of the G20 in global affairs and Africa’s recent admission to the group, it also represents an important forum to address Africa’s climate priorities.

The Indonesian and Indian presidencies spanned a period of unprecedented global crises. Indonesia took over the G20 presidency in 2022, when the COVID-19 pandemic and climate-related challenges globally caused an economic downturn and slowed recovery. It was also the year in which the Russia–Ukraine war started, further disrupting global supply chains and leading to a rise in energy and food prices worldwide. Very little changed in the underlying international conditions during the Indian presidency in 2023. Given these challenges, it is unsurprising that the Indonesian and Indian presidencies focused on solutions to the climate, energy and development crises.

The 2022 Bali G20 Leaders’ Declaration supported accelerating sustainable, just, affordable, and inclusive energy transitions and the flow of sustainable investments. The leaders committed to achieving net-zero GHG emissions by the middle of the century and called for affordable, reliable and modern energy systems for developing countries. The Bali Energy Transition Roadmap identified three priorities for action – securing energy accessibility, scaling up smart and clean energy technologies and advancing clean energy financing. For each of these priorities, the roadmap established milestones for 2030, essential actions to be taken, the expected deliverables and the organisations and groups responsible for undertaking the relevant work.1G20 Indonesia 2022, Bali Leaders Declaration, 2, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/60201/2022-11-16-g20-declaration-data.pdf

In the area of innovative finance toward low GHG emissions and a climate-resilient future, it was agreed to mobilise finance from both public and private sources and support a shift from unsustainable to green economic activities. It was also decided to scale up climate-friendly finance and investments and to reduce counterproductive fossil fuel subsidies while accelerating technological solutions and green energy industrial development programmes. To reduce GHG emissions and promote a climate-resilient future, countries were encouraged to introduce and leverage carbon pricing policy instruments.

The Indian G20 presidency reinforced decisions on the just energy transition and sustainable financing taken during the Indonesian presidency. In the 2023 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration, it was resolved to pursue low-GHG/low-carbon emissions and climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable development. They had earlier committed to achieving net-zero emissions although there was no agreement on phasing out fossil fuels.2African Climate Wire, “G20 Ministers disagree on Fossil Fuel Phaseout”, https://africanclimatewire.org/update/g20-ministers-disagree-on-fossil-fuel-phaseout/ The leaders also committed to accelerating clean, sustainable, just, affordable and inclusive energy transitions. The needs, vulnerabilities, priorities and different circumstances of developing countries were recognised. The leaders supported voluntary and mutually agreed technology transfers and access to low-cost finance by developing countries.3G20 India 2023, “New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration”, 4, http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2023/230909-declaration.html

The New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration adopted the G20 High-Level Principles on Lifestyles for Sustainable Development. This was based on the work of Think20’s Task Force 3, which showed that embracing sustainable production and consumption patterns could contribute to significant emission reductions by 2030 for a global net-zero future.

Think20’s Task Force 4 report on low-cost financing for the energy transition estimated that developing countries would need about $5.8–5.9 trillion in the pre-2030 period to implement their NDCs. They would also need $4 trillion annually for clean energy technologies by 2030 to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.4Li Fang et al., “Unlocking Sustainable Finance To Accelerate A Just Energy Transition” (Think20 Policy Briefing, Task Force 4, Delhi, 2023), 4. The leaders resolved to work towards facilitating access to low-cost financing for developing countries, new and emerging clean and sustainable energy technologies and supporting energy transitions.

Developed countries also reaffirmed their 2010 commitment to provide $100 billion per year in climate finance to developing countries by 2020. They indicated that this goal would be met for the first time in 2023. Finally, the leaders resolved to implement the decision taken at COP27 to establish the Loss and Damage Fund to assist climate-vulnerable developing countries.

Assessing the implications of the Indonesian and Indian G20 presidencies for African priorities

This section takes a critical look at how the Indonesian and Indian G20 presidencies have addressed African concerns and priorities in the areas of sustainable finance and a just energy transition.

Sustainable finance

Regarding climate finance, decisions taken during the Indonesian and Indian G20 presidencies have tended to lump all developing countries together. They have not sufficiently addressed the special needs of Africa in several ways. First, although Africa is the continent most affected by climate change, it has received the least amount of climate finance flows. For example, between 2010 and 2015, $212 billion worth of climate finance was disbursed, with $81 billion (48%) going to Asia and $48 billion (23%) going to Africa (Figure 1). In 2016–2019, Africa’s share of global climate finance flows increased to $73 billion (26%).5John Asafu-Adjaye, “Climate Action for Africa at COP27” (Policy Brief, African Center for Economic Transformation, Accra, 2022), 3.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Climate Finance Provided and Mobilized by Developed Countries in 2013–18 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020).

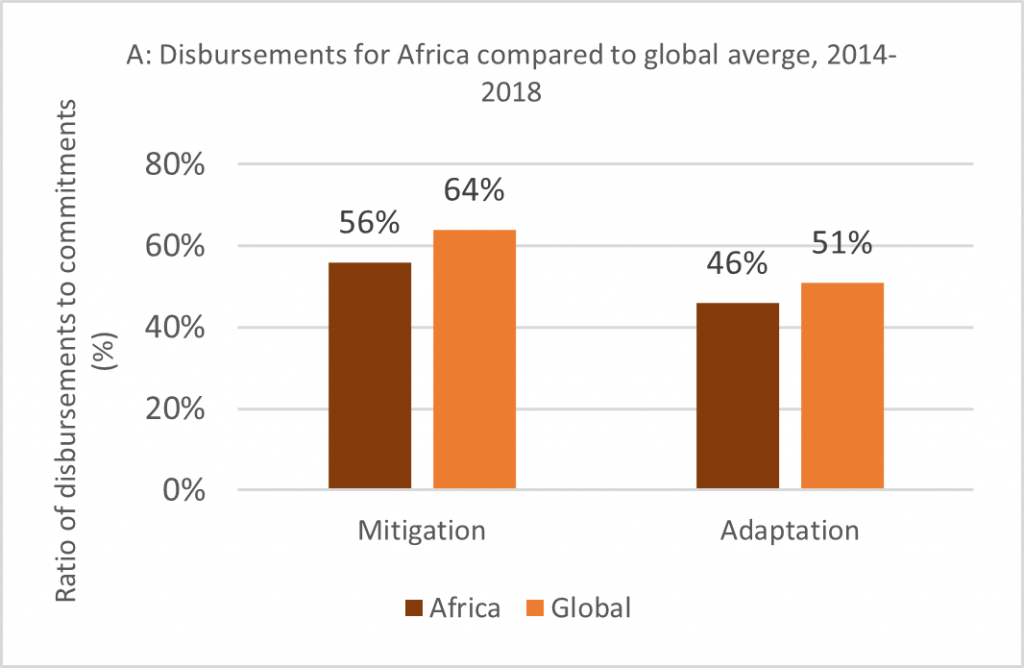

Figure 2a shows data for the ratio of disbursements to commitments for climate finance for Africa compared to the global average for 2014–18. Mitigation and adaptation disbursements to Africa were 56% and 46%, respectively, of the corresponding commitments for the period. Figure 2b shows that for some African regions such as North Africa and Central Africa the disbursement ratios were well below the global average.6Asafu-Adjaye, “Climate Action for Africa”, 3.

Figure 2: Climate finance provided and mobilised by developed countries in 2014–18

Source: Georgia Savvidou et al., “Quantifying International Public Finance for Climate Change Adaptation in Africa”, Climate Policy 21, no. 8 (2021): 1020–1036

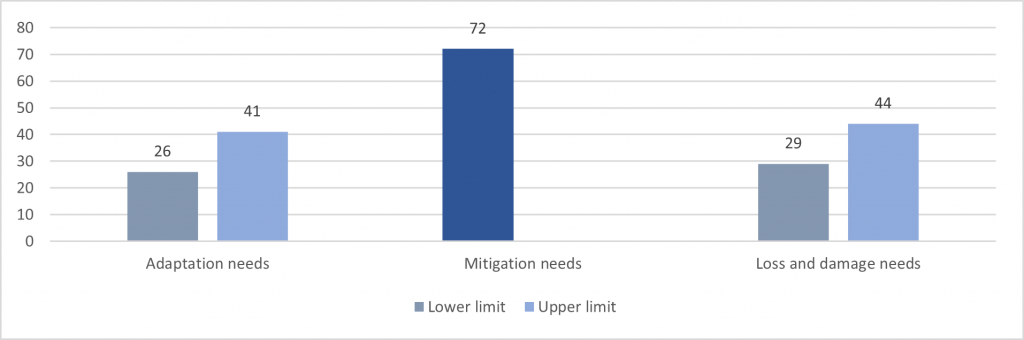

Second, the New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration states that developing countries need around $5.8–5.9 trillion by 2030 to implement their NDCs. 7G20 India 2023, “New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration”, 4. However, this overall figure masks Africa’s onerous financing needs. Africa’s adaptation costs for 2020–2030 alone are estimated to range from at least $259 billion to $407 billion, representing an annual average need of between $26 billion and $41 billion (Figure 3).8Mahmoud Mohieldin, Bogolo Kenewendo and Reuben Wambui, “Breaking Financing Barriers for a Just Climate Transition in Africa” (ACET, Accra, November 1, 2023), 9. Mitigation needs are estimated to be approximately $715 billion over the same period, averaging about $72 billion annually.9Asafu-Adjaye, “Climate Action for Africa”, 5.

Additionally, the projected loss and damage costs for Africa between 2020 and 2030 range between $289 billion and $441 billion.10Africa NDC Hub, Africa’s NDC Journey and the Imperative for Climate Finance Innovation (Addis Ababa: Africa NDC Hub, 2021), 5.

Figure 3: Annual climate needs in Africa ($ billions)

Source: Africa NDC Hub, Africa’s NDC Journey and the Imperative for Climate Finance Innovation (Addis Ababa: Africa NDC Hub, 2021)

African countries receive a grossly insufficient amount of climate finance, falling far short of their requirements.11Asafu-Adjaye, “Climate Action for Africa”, 3. For 2020–2030, Africa’s average annual climate funding needs are estimated at around $142 billion, compared to the current inflow of about $30 billion per year. If the same level of climate funding persists throughout 2020–2030, there will be an annual shortfall of $112 billion, amounting to a total climate finance gap of $1.1 trillion.12Asafu-Adjaye, “Climate Action for Africa”, 3. At COP26, developed countries promised to double global adaptation funding by 2025, amounting to an additional $40 billion per year for Africa. However, Africa would still face a total shortfall of at least $820 million for the decade.

The other issue not recognised in the G20 declarations is that climate mitigation attracts more finance than adaptation. Globally, mitigation accounted for 59% of climate-related development finance going to developing countries between 2010 and 2019, while adaptation accounted for 31%.13Asafu-Adjaye, “Climate Action for Africa”, 4. The funding trend for Africa was similar, with 48% of climate finance going towards mitigation compared to 41% for adaptation between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 4).14Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013–18: Key Highlights (Paris: OECD, 2020), 6. Other issues, some of which are discussed below, include the high debt burdens African countries are carrying and the high cost of climate finance.

Figure 4: Share of average annual climate finance by theme in Africa, 2010–2019 (%)

Source: OECD, Climate Finance Provided and Mobilized

Inaction on climate finance is worsening living standards on the continent. Based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predictions that put the world on track for a temperature rise of roughly 3C by the end of the century, a study predicts that many African countries will likely witness a decline in their long-term gross domestic product (GDP).15UN Environment Programme, Broken Record: Temperatures Hit New Highs, Yet World Fails to Cut Emissions (Again), Emissions Gap Report (Nairobi: UNEP, November 20, 2023). Owing to climate change, Africa loses $7–$15 billion annually, and this is expected to rise to $50 billion by 2040.16African Development Bank, “Leaders Summit on Climate: African Development Bank President Says the Continent Is ‘Ground Zero’ of the Crisis as Major Economies Boost Climate Targets”, August 23, 2021. Average losses across the continent are projected at 2% to 5% of GDP, up to 17% yearly in Côte d’Ivoire, almost 9% in Mozambique and 7% in Kenya.17Tom Kompas, Van Ha Pham and Tuong Nhu Che, “The Effects of Climate Change on GDP by Country and the Global Economic Gains from Complying with the Paris Climate Accord”, Earth’s Future 6, no. 8 (2018): 1153–1173.

Some countries are already spending up to 9% of their GDP to address natural disasters caused by climate change.18Anja Slaney, “Multiple Disasters and Debt Sustainability in Small Island Developing Countries” (UNCTAD Research Paper 55, UN Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva, December 2020).

Just energy transition

On the cost of the net-zero energy transition, it is important to note that the estimates of adaptation and mitigation costs in countries’ NDCs only account for direct costs. For example, they do not include the indirect costs (eg, job losses) of transitioning to low-carbon pathways. Empirical studies show that the net-zero transition will be acutely detrimental for livelihoods. A recent study estimates the cost of the net-zero transition to be equivalent to 6.8% of global GDP in 2021, rising to 8.8% from 2026 to 2030.19McKinsey Global Institute, The Net-Zero Transition: What It Would Cost, What It Would Bring, January 2022. The study indicates that to support economic development and build the low-carbon infrastructure needed to shift to net-zero GHGs, sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries must invest at least 1.5 times as much (as a share of GDP) as developed economies.

Following the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris, 45 of 54 African countries mentioned using strategies such as carbon pricing or carbon markets to help achieve the targets in their NDCs. A recent study of selected African countries shows that carbon-pricing policy instruments (eg, carbon taxes) could help achieve the targets in their NDCs.20John Asafu-Adjaye, A Just Energy Transition for African Countries, Report (Accra: ACET, August 2023). However, such measures will have flow-on effects leading to job losses in energy-intensive industries and increasing the prices of electricity and energy-intensive goods. The study concluded that a carbon tax is not a one-size-fits-all solution for African countries, particularly those with low per capita emissions and underdeveloped industrial sectors. Such countries could instead explore implicit carbon pricing (eg, removal of fossil fuel subsidies, fossil fuel taxes, etc.). Furthermore, these measures can go hand in hand with other schemes associated with offset carbon markets, such as the Clean Development Mechanism and REDD+21“Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries”. initiative.

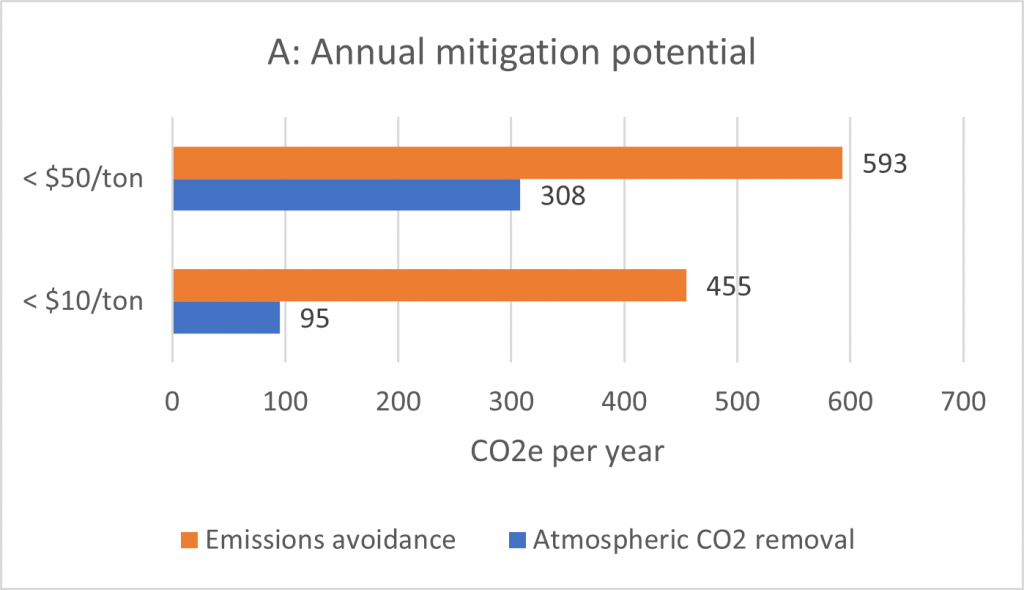

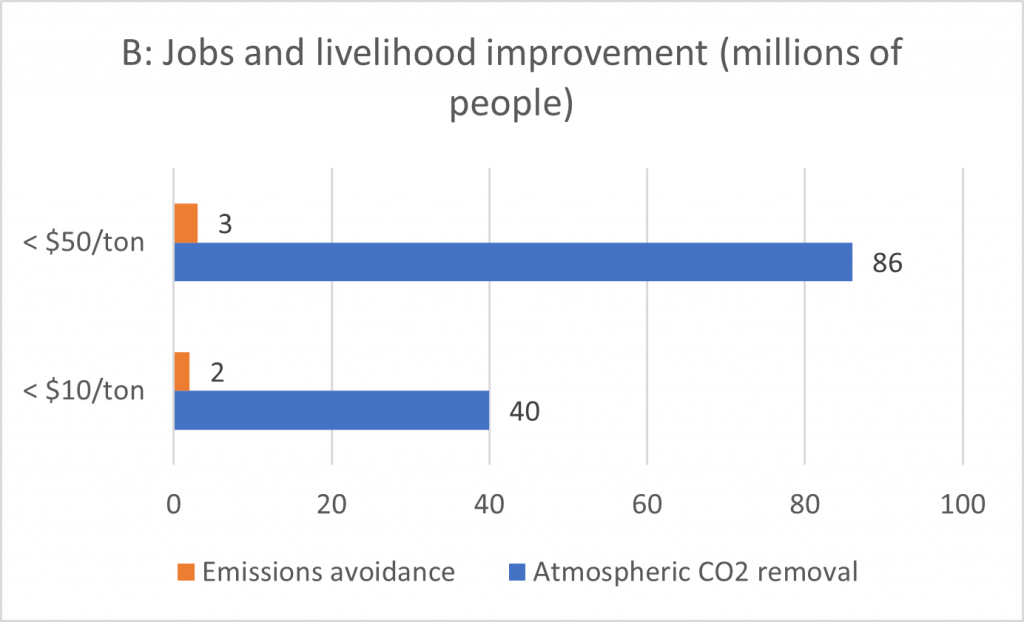

Despite its high costs, the net-zero energy transition can offer win-win opportunities for revenue generation/job creation and carbon mitigation. For example, at a carbon price of at least $50/tonne or less, nature-based solutions22Nature-based solutions include carbon removal practices such as tree planting on agricultural land, applying biochar and improving grazing practices. could create as many as 86 million jobs in Africa annually and remove 308 MtCO2e23Metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. through atmospheric CO2 removal and 593 MtCO2e through emission avoidance annually (Figure 5).24Emission avoidance includes emissions that would be associated with the amount of carbon sink that is at risk of being destroyed every year. This comes from carbon sink protection and optimal agricultural practices.

An issue relating to the energy transition that has not been sufficiently addressed by either the Indian or the Indonesian G20 presidency is how to accelerate electricity access in Africa, particularly SSA. In SSA, more than half of the population (57%) does not have access to electricity and only 17% have access to clean cooking solutions and must rely on biomass for their household thermal energy.25This assessment is based on the recommendations of Task Force 3 – Governing Climate Targets, Energy Transition and Environmental Protection, and Task Force 4 – Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions, as well as the leaders’ declarations. Africa holds 60% of the world’s best solar resources and 39% of global renewable energy potential.26Deborah Ramalope et al., Renewable Energy Transition in sub-Saharan Africa, Report (Berlin: Climate Analytics, November 2022). To date, however, African countries have largely been unable to take advantage of their abundant but underused renewable resources. In 2020, renewables accounted for only about 14% of the total energy supply, and in the electricity sector they accounted for about 22.1% of generation in 2019, with fossil fuels accounting for 77.1%.27International Energy Agency, Key World Energy Statistics (Paris: IEA, September 2021). In terms of investments, the continent has attracted only 2% of global investments in renewable energy over the past decade.28KfW et al., The Renewable Energy Transition in Africa: Powering Access, Resilience and Prosperity (Berlin: KWF, 2020). A major barrier to attracting finance for renewable energy development in Africa is the lack of capacity of the private and public sectors to develop bankable projects. Other challenges include the high cost of finance, biased credit assessments, and the perceived investment risk in the continent, some of which are further discussed below.

Figure 5: Mitigation and job creation potential of nature-based carbon removal

Source: Climate Action Platform-Africa, “Nature-Based Climate Mitigation”, https://capa.earthrise.media/

Looking ahead to the Brazilian and the South African presidencies

Based on the foregoing discussion, the Brazilian and South African G20 presidencies, with the support of the new permanent member, the AU, should focus on how to increase not only the flow of climate finance to the continent but also the quality of that finance.

For nearly all countries, access to external climate financing is crucial for achieving their NDCs. Many African countries are struggling to repay debts while rising inflation is driving up interest rates worldwide and increasing the cost of debt servicing. To add to these challenges, recent research shows that the transition to net-zero energy pathways is expected to lead to high public debt levels.29Franco Maldonado and Kevin P Gallagher, “Climate Change and IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis” (Working Paper 5, Task Force on Climate, Development and the International Monetary Fund, Boston, 2022). SSA’s public debt-to-GDP ratio now stands at 56%, 30Aaron O’Neil, “National Debt of Sub-Saharan Africa in Relation to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 2028”, Statista, November 29, 2023. with debt servicing surpassing recurrent expenses in some economies, leaving little to no room for climate financing from public funds.31Mohieldin, Kenewendo and Wambui, “Breaking Financing Barriers”, 15. There is therefore a need to push for more below-market interest rate loans or concessional capital to African and other emerging developing economies and to implement innovative financing mechanisms such as debt-for-nature swaps.

There is also a need to fast-track the decision to re-channel special drawing rights (SDRs) to multilateral development banks (MDBs) such as the African Development Bank to provide additional climate finance.32It was announced at a side event organised by the African Development Bank (AfDB) at the Africa Climate Summit 2023 that the AfDB and the IMF would formally announce the start of this initiative at COP28 in Dubai. G20 creditor countries should redesign the Common Framework for Debt Treatments to accelerate debt relief and cancellation as well as debt suspension, and permit debt-distressed middle-income nations to access the framework.

Africa can leverage its massive carbon stocks to increase the flow of climate finance through participation in carbon markets. According to one estimate, carbon markets could mobilise $6 billion per year by 2030 and more than $100 billion per year by 2050.33Solomon Elusoji, “Can Carbon Markets Help Africa Meet Its Climate Financing Goals?”, China Dialogue, April 27, 2023. However, African and other developing countries face several challenges in participating in carbon markets. These include a lack of local technical capacity and private investors’ perception of Africa as having a high level of risk.34African Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI), “Harnessing Carbon Markets for Africa”, Roadmap report, ACMI, November, 2022. This perception is based on various factors, such as limited infrastructure, poor governance and uncertain land tenure systems.

There is also a need to push to reform multilateral funders to address the challenges countries face in accessing finance. These challenges include requirements for co-financing, lack of support for developing concept notes, long timelines and lack of flexibility in the process leading to delays in funding applications. Finally, there are opportunities to increase climate finance from non-traditional sources, including the private sector, which accounted for only 14% of total flows in 2019–2020.35Chavi Meatle et al., Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa (Berlin: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022). The Brazilian and South African G20 presidencies can help address some of these issues. With its interest in carbon markets, Brazil can push for reforms to enhance the participation of developing countries. And South Africa can explore finance reforms across a wider financial network, including the BRICS.

Conclusion and recommendations

Although the continent contributes to less than 4% of global GHG emissions and bears the brunt of climate impacts, various African countries have submitted ambitious targets in their NDCs to contribute to the transition to net-zero economic pathways. Many African countries face debt challenges and have limited fiscal space to fund their NDCs. As such, the achievement of their NDCs depends on the availability of external finance. However, historically, Africa has received less climate finance than other regions. The Brazilian and South African G20 presidencies, supported by the AU, can help expedite the energy transition in Africa by advocating for the following interventions.

- Increasing the flow of climate finance to the continent:

- multilateral funders should establish a project development fund facility to provide funding and technical assistance supporting project identification, as well as the development of concept notes and bankable projects;

- African countries should seek technical assistance from MDBs and developed countries to build capacity in project management, business development skills, and management of large-scale renewable energy projects; and

- multilateral funders should undertake further reforms to address the challenges countries face in accessing finance, such as requirements for co-financing, lack of support for developing concept notes, long timelines and lack of flexibility in the process leading to delays in funding applications.

- Increasing the participation of African countries in international carbon markets. Here, there is a need to:

- increase capacity building and skills training in the development and management of renewable energy projects; and

- introduce land tenure reforms to enhance the participation of local communities and other private entities in carbon offset markets. The AU can assist by looking at the issue from a regional perspective and promoting best practices from other African and emerging economies.

- The capacity of African and other low- and middle-income countries to manage debt and climate challenges can be enhanced by:

- extending below-market rate or concessional capital to such countries;

- expediting the decision to re-channel SDRs to MDBs;

- redesigning the Common Framework for Debt Treatments to accelerate debt relief and cancellation or debt suspension for climate-vulnerable countries; and

- employing innovative instruments such as green bonds, green loans and debt-for-nature (or debt-for-climate) swaps. Measures such as green bonds can be expensive for the issuing governments. Private capital can be attracted by implementing measures such as credit guarantees and credit enhancement.

- A vastly underutilised source of climate finance in Africa is the private sector. Private sector participation can be enhanced by devising credit enhancement and credit guarantee schemes in project financing.

The AU, as a permanent member of the G20, can help advance the African agenda by taking up these issues at the leadership level. The AU can also promote regional collaboration to tackle financing barriers such as inadequate infrastructure, poor governance and inconsistent and uncertain policy and regulatory frameworks.