The ideology of the revolution was rooted in teachings spread by Ayatollah Khomeini. His firm belief in the need for jurists who were experts in Islamic law and could act as guardians of the people came to shape not only the revolution but the new constitution, system of government, and the electoral system.

Iran’s presidential elections took place on 19 May, with Hassan Rouhani emerging victorious to run for a second term. Views on the election’s outcomes are of course varied. While some hail the democratic exercise and look forward to change in one of the Middle East’s most influential countries, others with insight into the system’s inner workings know that change will be hard to come by due to the centralisation of true decision-making power in a position far above that of the president. Election outcomes are naturally interesting to consider and predict, but what begs greater attention is the process underlying the entire system which, once understood, reveals the elections to be one small cog in the greater machine of state control that is Iran’s brand of governance.

At face value, without investigating Iran’s electoral system, many incorrectly assume the diagram below to be an accurate representation of the process.

Source: Carmel Rawhani, 2017

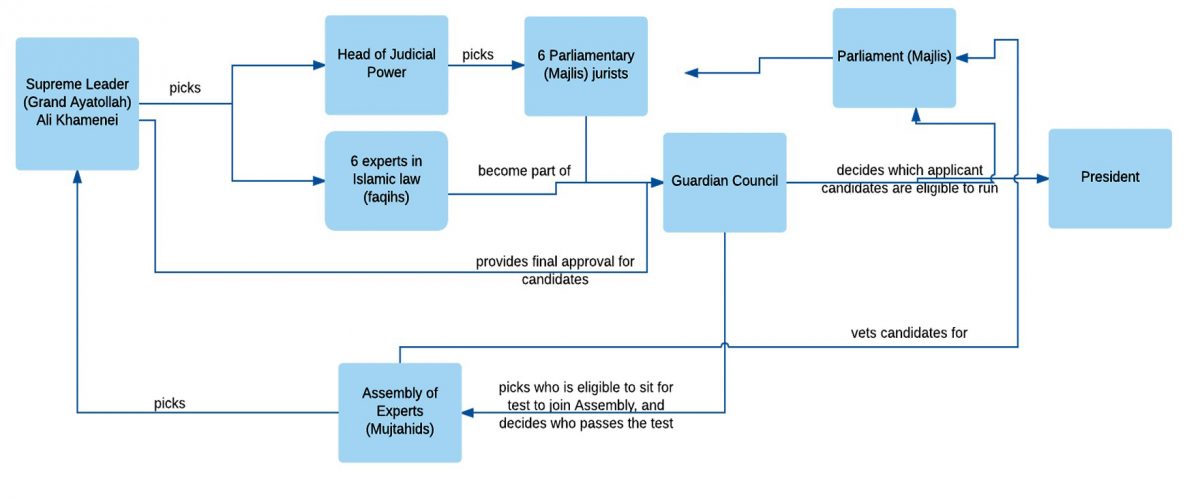

In truth, the system of intertwined checks and balances instituted by Iran’s leadership resembles a web far more complex than a simple straight line. The system deliberately diverts any and all power away from figurehead positions like the president, and channels true power and authority to those bodies which combine political and religious control, as shown in the diagram below

Source: Carmel Rawhani, 2017

In order to understand exactly how important the Iranian president is vis-à-vis the supreme leader, and thereby understand the true significant of presidential elections, it is helpful to clarify what they can each do, and how they come to power. Supreme Leader Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is the head of state. Far from being a figurehead, Khamenei has ultimate authority on all decisions. He fulfils the function of commander-in-chief and makes conclusive decisions on all matters to do with the economy, environment, for policy, and national planning. Beyond controlling the military he also has the final say on all media and exerts ultimate control (whether directly or indirectly) over the legislative, executive, and the judicial branches of government. Khamenei chooses six experts in Islamic law, who along with six parliamentary jurists (from the Majlis – parliament ), chosen by the Head of Judicial Power, who is in turn chosen by the Supreme Leader, from the 12-person Guardian Council. The parliamentary jurists and Islamic legal experts are chosen to govern based on Khomeini’s belief in religious guardianship being the most pivotal aspect of Islam.

The Guardian Council acts as a ‘gateway’ between state control and popular elections, as it is this council which decides who is eligible to stand for parliamentary elections. While the parliament has the power of oversight and legislation, these are largely controlled by the Guardian Council and the Supreme Leader in turn. Any law put forward by the parliament must be approved of by the Guardian Council, and any oversight exercises such as investigation or review of people in office, particularly people in the Supreme Leader’s office, must be overseen and approved of by the Supreme Leader himself. The Guardian Council also decides who qualifies to write the test to apply for membership in the Assembly of Experts (Mujtahids), as well as who passes the test. The Assembly of Experts is elected by direct popular vote – based on who qualifies after passing the test. After the election, the Supreme Leader must approve of any candidate before he or she can join the Assembly, whose most important function is to pick the Supreme Leader. The Assembly has become a largely ceremonial body and largely focuses on keeping a list of candidates from whom the next Supreme Leader will be chosen after Khamenei’s passing.

The president is also elected by direct popular vote, but only after candidates have been thoroughly vetted and selected by the Guardian Council. Thus, while presidential elections attract much media fanfare both in Iran and across the globe, they are hardly the catalysts of transformative change that external analysts predict.

One of the main internal criticisms brought against Iran’s previous (and pre-revolution) government under the Shah (the King), was that elections slowly slipped away and public bodies were dominated by the Shah’s nepotism and power to select whomsoever he pleased for the position of his choice. With that history in mind, the government has couched Iranian elections in the rhetoric of participation in the expression of public opinion. As with elections the world over, the gap between rhetoric and action remains large, and in the absence of accurately implementing new systems, falling into old patterns becomes all too easy.