Recommendations

- Improve the website, making it a comprehensive, user-friendly online knowledge repository.

- Be tougher on members that close the civic space, do not implement NPoAs, do not report timeously and/or do not pay voluntary member fees.

- Further elevate the oversight role of civil society in the process.

- Establish a civil society desk at the Secretariat to focus activities.

- Improve peer learning on identified best practices.

- Produce clear research on evidence of the APRM’s impact.

- Revise existing procedures and documents.

Executive summary

The African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) is an example of a multi-stakeholder initiative (MSI). Such frameworks became prominent in the early 21st century, bringing together governments, business and civil society to collectively solve governance challenges. While the APRM is a uniquely African MSI, SAIIA’s research has also looked at other, global initiatives, focusing on the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). The purpose of this policy briefing is to provide practical policy recommendations on what the APRM can learn from its counterparts and, in turn, what it can teach them. It is important for MSIs to continually evolve and adopt best practices to maintain their edge in the constantly changing world of international development.

Introduction

This policy briefing examines what lessons the APRM could learn from two similar initiatives – the OGP and the EITI – and in turn, what they might learn from the APRM.

The APRM, OGP and EITI are all MSIs – partnerships between governments, civil society and the private sector that have been a feature in international development since the early 21st century. They aim to collaboratively address socio-economic challenges, improve governance practices and strengthen laws and policies. They are based on the premise that good governance can be achieved through increased and more meaningful cooperation and improved transparency.

The APRM is the oldest and most comprehensive MSI discussed here. It is wide-ranging in scope, assessing democracy and political governance, economic governance and management, corporate governance, and socio-economic development in a given country. Membership is open to all states of the AU, and 38 have joined since 2003. The APRM’s primary focus is non-adversarial peer reviews, which encourage sharing best practices and coming up with ‘African solutions to African problems’. The ‘partners’ are governments, with civil society and the private sector invited to participate, but not on an equal footing.

In comparison, the OGP is younger, and its mandate has four much narrower areas: fiscal transparency, access to information, income and asset disclosure, and citizen engagement. Established in 2011, the OGP is global in its membership and includes 79 national and 20 sub-national governments. These work with civil society to undergo reviews every two years and work on commitments contained in individual National Action Plans. Governments and civil society are more equal partners in this initiative, exemplified by the composition of the OGP Steering Committee, with 12 government and 12 civil society representatives.

While the EITI is the same age as the APRM, of the three MSIs discussed here its focus is the narrowest. The EITI is primarily concerned with governance of natural resources in the oil, gas and mining sectors. The process is, however, flexible enough that some member states have included forestry and agriculture. There are currently 52 member states, although seven are suspended. Participants are required to adhere to the EITI Standard and to publish timely and accurate information on the management of natural resources. The private sector, specifically companies working on extractives, plays a significant role in the EITI, including in the tripartite Multi-Stakeholder Groups that steer the process.

The APRM has been in existence for 16 years and recognises the need to re-examine its processes and systems, for instance through its ‘Deepening the Review’ task force. There is much it can learn from – and teach – other MSIs.

Improve website, making it a comprehensive, user-friendly knowledge repository

The APRM’s website is difficult to navigate, is infrequently updated, and is missing key documents and information. This has been the case since the mechanism was established. Some improvements have been made, and a social media presence was added in 2014.[1] Since then, social media channels have functioned commendably, informing stakeholders about the latest news and developments. The website, however, remains inadequate. It is difficult to find documents and key publications, such as National Programme of Action (NPoA) Implementation Reports, are still missing.

The OGP and the EITI by contrast have excellent, modern websites. They provide easily searchable, well-organised material for all as part of their commitment to transparency. Unlike the APRM’s site, they are user-friendly and comprehensive knowledge repositories.

Be tougher on members that close the civic space, do not implement NPoAs, do not report timeously and/or do not pay member fees

According to the APRM’s founding documents, if the ‘necessary political will is not forthcoming from the Government’ and all efforts to engage it in constructive dialogue have been unsuccessful, ‘the participating Heads of State and Government may wish to put the Government on notice of their collective intention to proceed with appropriate measures by a given date’.[2] This is the only (rather vague) mention of any disciplinary action in APRM documents, but it has never been implemented. The only member to be temporarily barred from the mechanism has been Mauritania, in 2008, when it was suspended from all AU activities. Pre-emptive action could have prevented violence in South Africa, Kenya, Uganda, Mali and Mozambique, the potential for which was flagged in the relevant country review reports. There is a reluctance to ‘name and shame’ in African institutions, but this should not compromise the ability of the APRM to hold its member states to account for poor governance. Both the OGP and the EITI, on the other hand, have been more successful in dealing with recalcitrant members. The former renders members ‘inactive’ for infractions such as closing down the civic space or no longer meeting eligibility criteria. The latter similarly suspends or even delists members for lack of progress in implementing the EITI or if the political situation in the country does not allow EITI processes to function as intended.[3]

Further elevate the oversight role of civil society in the process

Civil society organisations (CSOs) play an important role during the APRM review – in most instances. Some of the more authoritarian APRM members ran tightly controlled review processes with little space for input from those outside the government. The continental APRM leadership, however, did not publicly condemn such behaviour. Both the OGP and the EITI have been protective of civic space and have confronted and suspended governments that do not respect it. This would be a good practice for the APRM to take on board. Similarly, it would do well to elevate the overall status of civil society in the process, especially in implementing NPoAs.

Also, representatives of civil society are typically asked to leave when review reports are discussed by heads of state at the APRM Forum. This practice needs to stop – all discussions, including those at the highest level, should be public and open to all stakeholders. Consideration should be given to adopting the Independent Review Mechanism of the OGP, where there is independent reporting on implementation apart from the government’s own reporting requirements. At the moment, there is no means of verifying governments’ claims about what they have done.

Establish a civil society desk at the Secretariat

Related to the point above, the APRM Secretariat should establish a civil society desk to liaise with and provide focused support to CSOs across the continent. Organisations that could play a meaningful role in the APRM are intimidated by its complex processes, technical jargon and focus on government stakeholders. Yet the APRM is, at its core, a process for assessing and improving governance. CSOs working on issues such as democracy, health or poverty alleviation can share their knowledge and provide practical solutions. The APRM Secretariat should have a dedicated contact person to answer their queries, provide capacity building and assist with funding for workshops and written submissions. The OGP Steering Committee, with equal representation of governments and CSOs, may be an institution worth emulating for the APRM to increase the involvement of civil society. Similarly, each EITI-implementing state needs to establish a Multi-Stakeholder Group with representatives from government, the private sector and civil society. The convening of heads of APRM National Governing Councils in recent years is an important step to increasing civil society involvement, as these bodies are usually chaired by a non-state actor.

Improve peer learning on identified best practices

Although only the APRM has the term ‘peer’ embedded in its name, all three MSIs discussed here emphasise the importance of ‘peer learning’, at national and international levels. The APRM Forum provides an opportunity to discuss governance practices and access peer learning at the highest level, between participating heads of state. ‘Best practices’ are highlighted in country review reports to allow others to learn from and possibly adopt them. These are useful tools in theory, but have proved lacking in practice. Forum meetings are poorly attended and heads of state are reluctant to criticise one another. Little has also been done to engage practically with other countries on identified best practices, which tend to remain on the pages of the reports. ‘Best practices’ should be described more fully in the reports, as solid case studies of relevance to other states. The APRM needs to create more opportunities for stakeholders, including government and civil society representatives, to engage on these, through peer-learning workshops, webinars, and bilateral and multilateral forums, which are conducted by the OGP and the EITI. Attendance at the APRM Forum, and critical engagements once there, are issues that are more difficult to address. Political will is crucial, and it cannot be forced on leaders.

Produce clear research on impact

As recent SAIIA research notes, ‘MSIs are undoubtedly useful governance-improvement tools, but measuring their effects and outcomes is not straightforward.’[4] The APRM is no exception. Over the 16 years of its existence it has produced 22 mostly solid, informative, honest and comprehensive governance assessments of its member states, as well as three second-generation reviews. It has also held numerous workshops and conferences for government officials and civil society representatives to discuss governance, democracy and accountability. Its contribution to improving governance on the continent has been immense.

Yet what has been its practical impact? This question is difficult to answer and the same applies to the OGP and the EITI. It is often easier to speak of ‘contribution’ rather than ‘attribution’ when it comes to influencing governance processes and policies. The APRM should conduct or commission a comprehensive study that looks at its impact at the national level, in terms of measurable activities such as laws passed and other governance policy changes made as a result of the review process, across all reviewed countries. This is a challenge for all three MSIs, which should share lessons with one another about attempts to measure their impact.

Revise existing procedures and documents

Throughout its existence, the APRM has undergone a few major changes, over significant intervals of time. The first of these was revising the Self-Assessment Questionnaire in 2012. During the same year the APRM also introduced the Committee of Focal Points (consisting of ministers responsible for the APRM in member states). Then, as part of the AU reform process, the APRM was given an expanded mandate in 2017, being asked to monitor progress on implementation of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and the AU’s Agenda 2063 development plan.[5] On the other hand, both the OGP and the EITI have shown more willingness to continuously change and evolve. The former constantly introduced additional requirements for civil society participation, as well as measures to protect civic space. The latter similarly keeps updating the standard against which countries are assessed. The APRM would do well to tweak existing procedures and rules to streamline the process, while also revising the arguably outdated and overly onerous questionnaire. The APRM’s task team on ‘Deepening the Review’ could be a good vehicle for identifying the changes required.

Conclusion

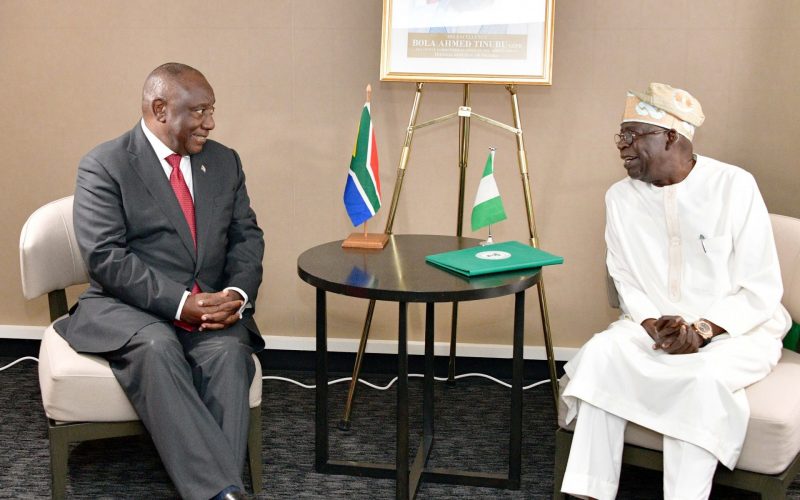

Although this briefing has mainly looked at what the APRM can learn from its counterparts, learning is a two-way street and Africa’s peer review process can provide important lessons for the OGP and the EITI. One of these is the strong strategic partnerships that the APRM has developed over the years. These partners include high-profile organisations such as the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, African Development Bank Group, African Capacity Building Foundation, UN Development Programme and UN Economic Commission on Africa.[6] The APRM has also been good at attracting new members, and strives for universal accession by all AU states by 2023 in spite of fears that this might ‘dilute’ its strength – ie, comprehensive and honest reviews. The APRM has also been signing Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with academic institutions and think tanks. Such partnerships help to strengthen its reach and provide additional external capacity. The OGP and EITI have also signed an MoU, in May 2018.[7] It is important that MSIs see each other’s efforts as complementary and not competitive. It is hoped that in the near future similar MoUs will be signed among all these initiatives.

Acknowledgement

SAIIA is extremely grateful to the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, who provided funding for this research.

Footnotes

[1] Turianskyi Y & J Grey-Johnson, ‘APRM and the Media: Getting the Story Right’, SAIIA (South African Institute of International Affairs) Occasional Paper, 171, January 2014, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/saia_sop_171_turianskyi-greyjohnson_20140213rev.pdf, accessed 5 July 2019.

[2] APRM (African Peer Review Mechanism) Base Document, 6th Summit of the NEPAD Heads of State and Government Implementation Committee, Abuja, 9 March 2003, p. 6, para 24, https://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/aprm-basedoc.pdf, accessed 8 July 2019.

[3] Turianskyi Y & M Chisiza, ‘Peer Pressure and Peer Learning in Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives’, USAID, April 2018, https://saiia.org.za/wpcontent/uploads/2018/08/2018-MSI-Peer-Review.pdf, accessed 3 May 2019.

[4] Gruzd S et al., ‘Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives: Lessons Learned’, USAID, April 2018, https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2018-MSIs-Lessons-Learned-Summary.pdf, accessed 4 July 2019.

[5] Turianskyi Y et al., ‘Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives: What Have We Learned? An Overview and Literature Review’, USAID, April 2018, https://www.saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2018-MSI-overview-literature-review.pdf, accessed 4 July 2019.

[6] APRM, ‘Strategic partners’, https://www.aprm-au.org/partners/, accessed 1 September 2019.

[7] Ibid