The forum will discuss how best African countries can maximise AGOA benefits until the expiration of this programme and to consider economic engagement post-AGOA. South Africa should leverage this opportunity to explore how future trade and investment ties with the US can be strengthened.

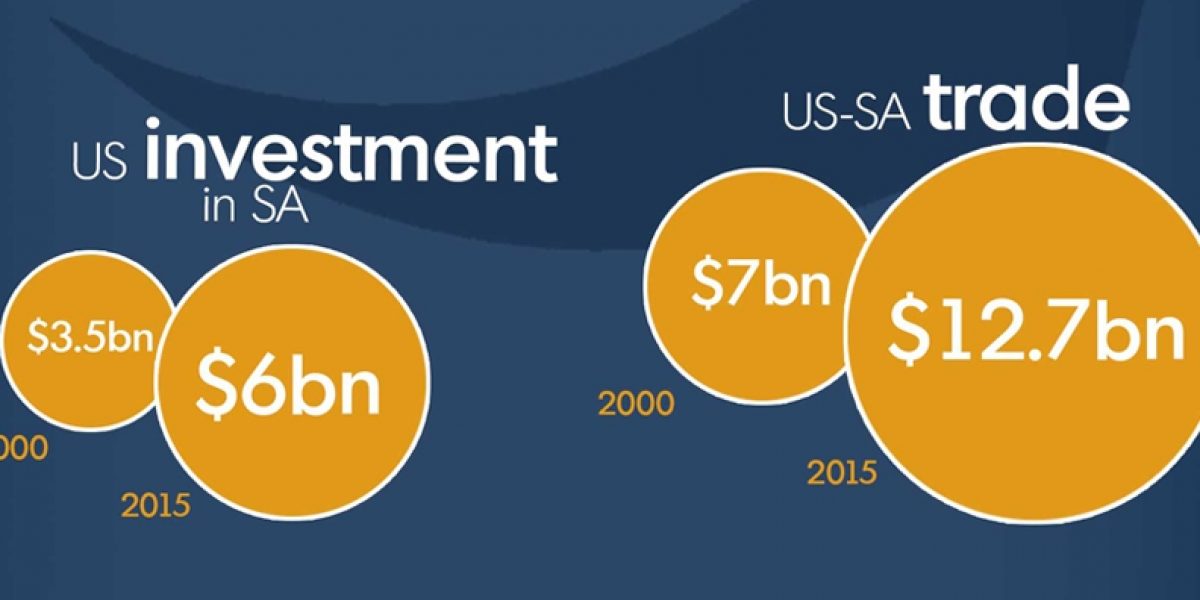

Over the past 15 years, the US has become an increasingly important economic partner for South Africa: total trade has nearly doubled since 2000, totalling $12.7 billion in 2015, with South Africa offering a diverse export portfolio and consistently maintaining a trade surplus with the US. During the same period US foreign direct investment into South Africa has also doubled, totalling more than $6 billion in 2015, representing 7% of total FDI in South Africa. By 2015 it was estimated that more than 600 US companies operated in South Africa, creating 100,000 jobs and adding roughly 10% to South Africa’s GDP.

Click here to read the related paper, ‘Maximising AGOA now while preparing for the future beyond AGOA’.

AGOA has, since the programme’s inception in 2000, been a boon to South Africa’s economy. The Department of Trade and Industry has suggested that more than 60,000 jobs are created in South Africa as a result of AGOA-preferences, notably in the automotive, metals and agriculture sectors. Yet, the country has struggled to take full advantage of this programme, utilising a mere 20% of duty free preferences extended under AGOA and other duty free programmes. By expanding knowledge of AGOA domestically, assisting South African exporters to better comply with US trade regulations and procedures, and matching domestic production capacities with preferences offered could see South Africa better leverage opportunities offered under AGOA.

In addition, given the unilateral nature of AGOA, a lack of a legislated dispute resolution mechanism to address trade and investment concerns has strained relations between parties, perhaps best illustrated earlier in 2016 when the US and South Africa went head-to-head over import regulations restricting meat exports from the US to South Africa. In lieu of a legislated dispute resolution mechanism, South Africa and the US should look to mitigate trade and investment disputes through established diplomatic channels.

Arguably more important, however, are future economic engagements with the US. The South Africa Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), in a recent policy briefing, has highlighted three options for consideration by South Africa on how trade and investment relations with the US can be strengthened post-AGOA.

The most comprehensive approach of the three options would be for South Africa to re-engage the US in talks around a free trade agreement (FTA). FTAs are comprehensive trade agreements, typically covering areas of trade and investment, which governs trade between parties. Previous negotiations between the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and the US around an FTA between 2003 and 2007 broke down, largely due to inflexibility from the US and lack of policy coherence within SACU. However, the global and domestic realities have changed considerably in the past decade. Globally, the stalemate reached in the current WTO round has prevented further liberalisation of markets. Equally, the global drop in demand and prices for commodities has significantly impacted commodity exporters such as South Africa. At the same time, the economic slowdown in South Africa, together with the government’s focus on export-led growth calls for more comprehensive engagements. Renewed talks of an FTA should therefore not be disregarded, as it would likely best promote trade and investment relations between the parties.

Secondly, the briefing offers a more moderate approach, suggesting South Africa should look to engage the US in a so-called ‘partial scope agreement’(PSA). PSAs, similar to FTAs, looks to create a legislated trade regime between parties. The defining difference is that unlike an FTA that comprehensively covers trade relations, PSAs allow for inclusion of select sectors and issues that all parties want to engage on. Not only will a PSA allow South Africa to be more strategic in the sectors it wants to engage on, but PSAs have also offered countries in the past an ideal platform to launch into an FTA. The US’ appetite for such an agreement has been questioned though, considering the high benchmark set by other multilateral agreements the country is party to, as well as the feasibility of such an agreement under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

The final option for South Africa to consider, is a ‘do nothing’ approach. By allowing AGOA to expire without putting an alternative trade regime in place will relegate trade between the parties to the WTO regime. Not only will this result in a significant reduction of duty free preferences for South Africa’s exports, it will forgo the opportunity to create an efficient and effective dispute resolution mechanism between the parties. While this approach is arguably the simplest of the three offered, it will do little to encourage US-South Africa economic relations by failing to provide incentives to the private sector and ensuring policy certainty.

Given the precarious position of the South African economy, the country cannot afford to not strengthen trade and investment ties with one of its key economic partners. The US’ historical engagement with the continent has clearly been driven by a combination of commercial diplomacy, foreign policy, and economic development imperatives. In choosing how to engage with the US going forward, South Africa should not lose sight of these drivers.

Click on an infographic below to enlarge.