Recommendations

- Establish mechanisms to integrate Indigenous knowledge and local priorities into climate resilience planning.

- Embed locally led adaptation (LLA) principles within national policies to align national adaptation strategies with local actions.

- Expand access to climate finance for LLA initiatives, prioritising decentralised mechanisms that empower local actors.

- Strengthen monitoring, evaluation and learning systems to assess LLA effectiveness and replicate successful approaches

Executive summary

Climate change imposes severe economic and social costs on Africa, with some nations allocating up to 9% of their budgets to climate disaster responses. Despite ambitious adaptation commitments by African governments, governance barriers and financial constraints continue to limit the effectiveness of these efforts. Locally led adaptation (LLA) has emerged as a transformative participatory strategy to ensure adaptation efforts are context-specific, inclusive and sustainable. However, successful implementation of LLA requires building on local solutions, improving access to finance and integrating Indigenous knowledge into national adaptation frameworks. This brief outlines the barriers, opportunities and policy recommendations for mainstreaming LLA in Africa, particularly in the food sector.

Introduction

Africa faces substantial risks from climate change. The continent is losing an estimated 2% – 5% of its GDP annually, and some nations divert up to 9% of their budgets to respond to climate change. These escalating costs strain national economies, reducing fiscal space for critical investments in agriculture, health and education.1World Meteorological Organization, State of the Climate in Africa 2023 (WMO, 2024) https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69000- state-of-the-climate-in-africa-2023.

Africa’s food systems, which are the economic backbone of most countries, are acutely vulnerable to climate shocks and stressors such as increasing temperatures, droughts, floods and erratic rainfall. For instance, in 2023, North Africa’s cereal production declined by 10% below the five-year average due to prolonged droughts, with Tunisia experiencing an 80% drop in output. In Sudan, erratic rainfall and dry spells led to forecast reductions of 25% in sorghum yields and a 50% decline in millet production. Meanwhile, extreme flooding in Ethiopia wiped out 72 000 hectares of crops and killed 27 000 livestock, devastating entire agro-pastoral communities. These impacts have broader economic and social consequences, exacerbating poverty, food insecurity and displacement. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s sixth assessment report estimates that by 2050, under Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5, which projects a 2.4°C increase in global warming, wheat yields and grain protein content will be reduced by 10% to 15% in North and East Africa, with a reduction of over 15% forecast for Southern Africa.

Africa’s exposure to, and capacity for adapting to these climate shocks is uneven and greatly influenced by intersecting social, political, economic and environmental factors. These factors determine whether and how different regions and communities are able to adapt. For instance, land tenure, access to education and gendered roles are key determinants of the adaptive capacities of rural farmers, especially among pastoral communities.2Edwige Marty et al, “Adapting to climate,” The Journal of Peasant Studies 50, no. 1 (2022): 136, https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.202 1.2010516; Lisa Murken and Christoph Gornott, “The Importance of Different Land Tenure Systems,”Climate Risk Management 35 (2022): 100419, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2022.100419.)

Without adaptation strategies that acknowledge and address these context-specific challenges, efforts to build resilience will continue to fall short. LLA offers a transformative, participatory solution. By centring decision-making at community level, LLA leverages Indigenous and local knowledge, strengthens local ownership and prioritises local needs when designing adaptation strategies. This approach enhances equity, inclusivity, and sustainability. Recognising that different groups experience climate shocks and stressors in different ways, LLA integrates diverse perspectives, making adaptation more effective across various social, economic and ecological contexts.

Policy landscape for climate adaptation in Africa

Africa’s Agenda 2063 envisions a continent that is environmentally sustainable and climate-resilient. The African Union’s Climate Change and Resilient Development Strategy and Action Plan (2022 – 2032), anchored in Agenda 2063, provides a framework for collective action and emphasises inclusion, alignment and cooperation across all levels – local, national and regional – to achieve Africa’s climate vision. This is also echoed in Article 7.2 of the Paris Agreement, which recognises the local, subnational, national and international dimensions of climate adaptation. In response, African governments have taken notable steps to strengthen climate adaptation, setting ambitious targets and integrating adaptation strategies into national policies and legal frameworks. Many countries have developed adaptation plans that include climate-smart policies, climate change action plans and response strategies. They often incorporate locally led initiatives aimed at building resilience from the ground up.

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) are central to global climate goals, outlining national commitments and approaches to climate adaptation and mitigation. The majority of Africa’s NDCs identify current, short- and long-term adaptation needs, priorities, goals and measures. Many of these also highlight localised concerns, including those of contextually relevant social groups that are disproportionately vulnerable to climate shocks. A World Wide Fund assessment3World Wide Fund, Scaling and Accelerating Adaptation in Food Systems in Africa (WWF, 2022). of African NDCs and NAPs found that 58% of NDCs and NAPs explicitly integrate gender into their adaptation measures. Furthermore, half of all NDCs and all NAPs address the needs of vulnerable or marginalised groups, including youth and older adults. However, a rapid analysis of 31 African NDCs by Financial Sector Deepening Africa revealed that although 28 mentioned gender or related terms, only 10 include a gender analysis to inform the content of their NDCs. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo incorporates an analysis of gender and Indigenous Peoples to inform adaptation measures in their updated NDC.4Munjal et al., A Rapid Analysis of the Gender Intentionality (FSD, 2023). Additionally, 13 included gender objectives and 14 stipulated gender actions within their priority mitigation and adaptation actions, with Kenya, Cameroon, Ghana and Namibia among those with clear measures to address gendered vulnerability in their NDCs. Despite the critical need for robust accountability frameworks, the report further notes that only seven NDCs incorporated sex-disaggregated data and indicators, and even fewer integrated gender-responsive budgeting into their climate action plans.

This analysis reveals that while some LLA principles are broadly highlighted and well-aligned, others are limited, lacking, or even neglected in different countries. This discrepancy, if not addressed, can result in poor implementation due to the absence of explicit emphasis on these principles in the policy documents.

Strengthening locally led adaptation through emerging practices and principles

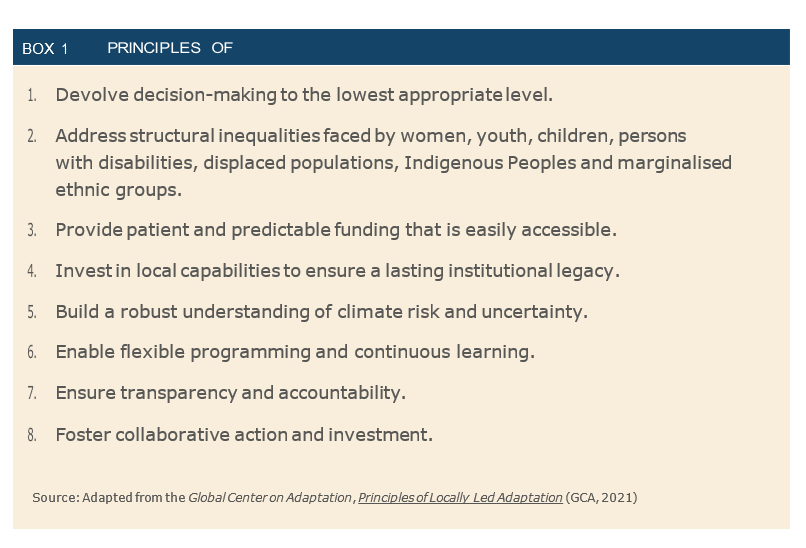

With the concept of LLA now more than two decades old, numerous good practices have emerged that provide a foundation for enhancing the involvement of local communities in adaptation and maximising adaptation benefits for them. A significant milestone in this evolution was the establishment of the Principles for LLA in 2021. These were developed through a peer partnership under the Global Commission on Adaptation, including the International Institute for Environment and Development and the World Resources Institute. The eight principles offer a clear standard for LLA and a coherent approach to adaptation, ensuring that various dimensions are considered in a balanced manner (See Box 1). Since then, various initiatives have emerged, serving as important reference points of the continued empowerment for local communities to lead the adaptation agenda.

Case Study: Farmer-managed natural regeneration in Niger

In Niger, the arid conditions of the Sahel region have led to severe land degradation, significantly impacting agro-sylvo-pastoral production. This degradation has resulted in reduced crop yields, soil erosion and biodiversity loss, threatening the livelihoods of farmers and pastoralists. Smallholder farmers, recognising the urgent need to restore their degraded land, have successfully implemented farmer-managed natural regeneration.5Climate & Development Knowledge Network, Inside Stories On Climate Compatible Development (CDKN, 2011). Despite progress in integrating locally led approaches into NDCs and NAPs, critical gaps remain that undermine alignment with LLA principles and hinder effective implementation. Slow policy execution, policy distortion, fragmented adaptation frameworks and timelines and inadequate systems for managing climate finance limit the effectiveness of NAPs. The complex, multi-actor nature of adaptation governance in Africa, spanning local, national and international levels, creates additional coordination challenges. The lack of clear leadership, governance mandates and integration across sectors and institutions often results in misaligned development and climate agendas. Political cycles and short-term appointments delay strategic decision-making, while uncertainty about future socioeconomic and emissions scenarios complicates long-term planning. Additionally, weak stakeholder participation, gender disparities in climate decision-making, and the concentration of adaptation resources among political and economic elites reduce the inclusivity and equity of adaptation efforts.6Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC, 2022).

This gap is evident in national climate policies, where gender considerations are often acknowledged but not meaningfully integrated. While many NDCs reference gender, only a fraction conduct in-depth gender analysis to inform their policies, raising concerns that these mentions may be more symbolic than substantive. Even in some initiatives believed to be locally led, a significant challenge remains the insufficient involvement of diverse community groups in the design, implementation and evaluation of adaptation programmes.

Financial constraints are another barrier. There remains a pronounced disconnect between identified needs and available funding, particularly for locally driven initiatives. Furthermore, many governments lack domestic financing mechanisms to sustain long-term adaptation efforts. African countries collectively require enormous investments to meet their climate goals – an estimated $2.8 trillion by 2030 to implement all African NDC targets7FSD Africa, The State of Climate Finance in Africa (FSD Africa, 2022).. Power imbalances between African states and developed nations influence access to climate finance, budget allocations and technology transfers – key resources for closing adaptation gaps. Within NDCs, the agriculture and adaptation components often come with large price tags that far exceed domestic budgets, meaning countries are counting on international climate finance that has been slow to materialise. This results in many adaptation actions remaining underfunded or dependent on piecemeal donor projects. At the subnational level, many institutions lack the financial resources, technical capacity or political autonomy needed to translate national policies into meaningful local action.

Moreover, complex application procedures for international funds, along with the limited accreditation of local organisations, result in funding being channelled through larger international programmes, which may not effectively reach local initiatives. Additionally, smaller-scale local projects struggle to meet donor criteria, creating a financing gap for locally led, community-level adaptation, further compounding the challenge of translating local climate strategies into actionable outcomes. For example, the current structure of financial products and services tends to work against smallholder farmers who cannot afford collateral or are deemed too risky. Given that Africa’s agriculture is dominated by smallholder farmers, the sector is characterised by low lending rates, incommensurate with the sector’s significant contribution to GDP.8The Making Finance Work for Africa (MFW4A) Partnership, Our Work: Agriculture Finance (MFW4A Secretariat, 2023). https://www.mfw4a.org/our-work/agriculture-finance. Limited access to financial resources and services, coupled with high costs of inputs, further hinders LLA.

Tracking progress is essential for adaptation processes. Yet, many countries lack robust monitoring and evaluation systems for climate actions, hindering the collection of comprehensive data on LLA implementation across Africa and making it difficult to support learning and adaptation. Without clear indicators of progress, implementation can drift off target unnoticed. Gender-specific monitoring is particularly weak, with few NDCs incorporating gender-disaggregated indicators, making it difficult to assess the differentiated impacts of climate adaptation efforts.

Enabling Local Climate Action

There are several opportunities for overcoming these challenges. First, mainstreaming climate in development and adaptation policies, including for the agriculture sector, would help ensure coherence in priorities and ambitions. This would strengthen the policy environment, which is crucial for safeguarding local actions. Second, it is important to explore solutions, ranging from innovative finance (eg, a mobile phone-based money transfer and financial services platform such as M-PESA in Kenya) to farm technologies that can unlock access to financial services, markets and resources that enhance livelihoods and resilience. These pathways require collaboration and partnerships, bringing together state and non-state actors and, most importantly, farmers. Governments of local and national levels are crucial in ensuring that policies and government programmes reflect community needs while leveraging local resources and expertise. Non-state actors, including the private sector, can also play a strategic role in scaling tested adaptation solutions and continuously strengthening local capacities. Partnership between farmers, extension services and technology providers is also important in fostering innovations that are tailored to local conditions. Finally, strengthening monitoring, evaluation and transparency at the community level (e.g, through social audits of climate adaptation projects) would enhance accountability and support more effective execution of plans.

Conclusion

The successful implementation of LLA depends on addressing institutional, structural and financial constraints that have historically marginalised local actors in climate governance. Strengthening governance mechanisms, improving direct access to climate finance, and promoting multilevel coordination are essential to embedding LLA into national and international adaptation frameworks. As climate challenges intensify, the integration of LLA principles will be vital to ensuring sustainable, inclusive and effective climate resilience across Africa.