Recommendations

- Public development banks need to adopt a gender-transformative approach to climate financing and influence other institutions to do the same.

- Public development banks should ensure staff are trained on the gender and climate change nexus, the meaning of gender and gender mainstreaming.

- Public development banks should apply transformational gender mainstreaming when developing climate financing operational frameworks and resource mobilisation strategies, applying climate finance instruments and deploying climate financial resources.

- Public development banks leadership teams should support transformational gender mainstreaming in climate-financing activities. This includes establishing gender units and focal point systems to put in place accountability mechanisms and align climate finance policies and practices with commitments to achieving gender equality.

Executive summary

The devastating impacts of climate change have already been felt across the world, resulting in a global urgency for climate action and rapid mobilisation of climate finance to support mitigation and adaptation to climate change. Women, men, boys and girls (of different ethnicity, identity, social class and status, age, race, dis/abilities, political setting and geographical location) are affected differently by the impacts of climate change. The differentiated impacts of climate change are shaped by gender inequalities. Gender equality is now acknowledged as a means for shaping effective climate change action, while climate finance is recognised as central to implementing gender equitable climate action. This policy brief provides insight into the mainstreaming of gender in climate finance and the public development banks’ commitment to supporting gender-responsive climate action. Among the key recommendations is the need to elevate the level of ambition by adopting a gender-transformative approach to climate financing.

Introduction

The disastrous impacts of climate change have already been felt across the world, underscoring the global urgency for action and rapid mobilisation of finance. The impacts are experienced differently across regions, nations, communities and social groups. Nations and people with lower coping and adaptive capacity are disproportionately affected.1International Panel on Climate Change, “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability”, (Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022). These differentiated experiences result from non-climatic factors and multidimensional inequalities, including those related to gender.

Gender2Gender refers to socially and culturally constructed differences between men and women, boys and girls. The concept includes norms, behaviours, abilities, roles, and responsibilities associated with being a woman, man, girl, or boy, as well as power relations between them. is among the fundamental factors shaping the way climate change affects women, men, boys and girls (of different ethnicity, identity, social class and status, age, race, dis/abilities, political setting and geographical location). Gender differences and inequalities are deeply rooted in socio-cultural norms, power relations, religious and political rights and institutionalised rules. These inequalities limit equal access to social and economic capital, productive resources, livelihood diversification, information, health services, education, skills and technology – all of which are vital in shaping the ability to respond to climate change.3Value for Women, “Study of the Impacts of Climate Change on the Women and Men of the Caribbean: Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience Countries”, Technical Note No IDB-TN-02064, (Inter-American Development Bank, December 2020).

Studies reveal that women and girls – especially across the Global South – often bear the brunt of climatic shocks and stressors compared to men and boys.4Women Deliver, “The Link Between Climate Change and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: An Evidence Review”, (January 2021): endnote 2. Though not universally vulnerable, research shows that women and girls tend to shoulder much of the responsibility for the family’s welfare, face higher health risks, are exposed to hygiene and sanitation challenges and experience heightened vulnerability to all forms of genderbased violence and abuse –including sexual violence, human trafficking and child forced marriages.5Madhulika Khanna and Nishtha Kochhar, “Do Marriage Markets Respond to a Natural Disaster? The Impact of Flooding of River Kosi in India”, (July 6, 2020), available at SSRN. This does not mean that men and boys are immune to the impacts of climate change. They also have unique vulnerabilities that should be addressed through changes in policies and practices. When exposed to climate stressors, they also face situations where expectations about their manhood or boyhood limit their options.6Eunice B. Ongoro and William Ogara, 2012, “Impact of Climate Change and Gender Roles in Community Adaptation: A Case Study of Pastoralists in Samburu East District, Kenya,” International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 4 no. 2 (2021): 78–89. It is unfortunate that their specific exposures, vulnerabilities, responses and capacity to respond to the impacts of climate change are rarely documented. Hence, the full picture of how gender interacts with climate change is incomplete. Failure to draw on the differentiated experiences of women, men, boys and girls, results in the loss of vital knowledge needed to inform effective climate action and financing.

Owing to gender-differentiated climate impacts, vulnerabilities and responses, links between gender and climate change have been gaining recognition. Gender equality7Gender equality refers to the equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women, men, girls and boys. It does not imply sameness. It is not a women’s issue. It concerns and fully engages all genders while recognising that neither all men nor all women are a homogenous group. is now widely acknowledged as a means for shaping effective climate change action. A mandate to mainstream gender in climate action is now outlined in several key documents of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), such as its Gender Mandate Guide, the Lima Work Programme on Gender, the Gender Action Plan, and the Paris Agreement.

Climate finance is recognised as central to implementing gender equitable climate action. It can catalyse climate actions that either alleviate or intensify gender inequality. It is therefore vital to explicitly consider gender-differentiated impacts and responses in climate-finance design and operationalisation.

The UNFCCC refers to climate finance as ‘local, national, or transnational financing – drawn from public, private and alternative sources of financing – that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change’.8UNFCCC Secretariat, “Introduction to Climate Finance”, UN Climate Change

Most climate financing comes from public sources. These include development financial institutions, governments and state-owned financial institutions and enterprises. Private actors – including commercial financial institutions, corporations, project developers, households and individuals – are increasingly supporting climate initiatives.9Barbara Buchner et al., “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021”, (Climate Policy Initiative: 2021).

Mainstreaming gender in climate finance

Gender mainstreaming is a process of assessing the implications for women and girls, men and boys of any planned action, including legislation, policies, or programmes in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making the experiences and concerns of all people, regardless of gender, an integral part of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres, so that different gender groups benefit equally, and inequality is not perpetuated. The goal of gender mainstreaming is to achieve gender equality.10Adaptation Fund, “A Study on Intersectional Approaches to Gender Mainstreaming in Adaptation-relevant Interventions”, (AFB/B.37-38/Inf.1: February 17, 2022).

Mainstreaming gender in climate finance should begin with a clear understanding of the gender and climate change nexus and the concepts underlying it. Gender and climate change are intrinsically intertwined. Tackling one without paying attention to the other undermines the effectiveness of policy interventions. A gender analysis11Gender analysis highlights the differences between and among women, men, girls, and boys in terms of their relative distribution of resources, opportunities, constraints, and power in a given context. is required to ensure that gender issues are effectively integrated into climate actions. These should then inform the development of climate financing frameworks and resource mobilisation strategies, the application of climate finance instruments, and the deployment of financial resources. Failure undermines gender mainstreaming and can perpetuate existing inequalities.

Mainstreaming gender in climate finance enhances returns on gender equality and climate change, supports the achievement of the UN Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and increases financial returns while lowering investment risk.12Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research et al., “Mainstreaming Gender-Smart Investing to Accelerate the Transformation of Food Systems Under a Changing Climate”, (November 2021). It promotes effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability of gender equitable adaptation and mitigation financing.

Outlook on gender mainstreaming in climate financing

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report and other studies reveal that climate financing does not have a good record of considering gender.13IPCC, “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability”, (2022); Women in Finance Climate Action Group, “Women in Finance Climate Action Group Report”, (2021); Barbara Buchner et al., “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019”, (Climate Policy Initiative, 2019). This is partly attributed to the limited emphasis on gender in climate change actions that should inform finance activities. For example, the Paris Agreement adopted at COP21, while not entirely silent on gender issues, failed to integrate gender-specific language in its mitigation, technology and finance sections. Gender issues were found to be inadequately considered in the first round of the nationally determined contributions.14Women Gender Constituency, “What Should I Know About Gender Equality in New and Updated NDCs?”, (2021).

Initially, not even the main vehicle for international climate policy, the UNFCCC, considered gender in its operationalisation. It therefore took time for gender considerations to gain a foothold in international climate change negotiations. Constant pressure from activists, civil society organisations and various other groups resulted in some change.

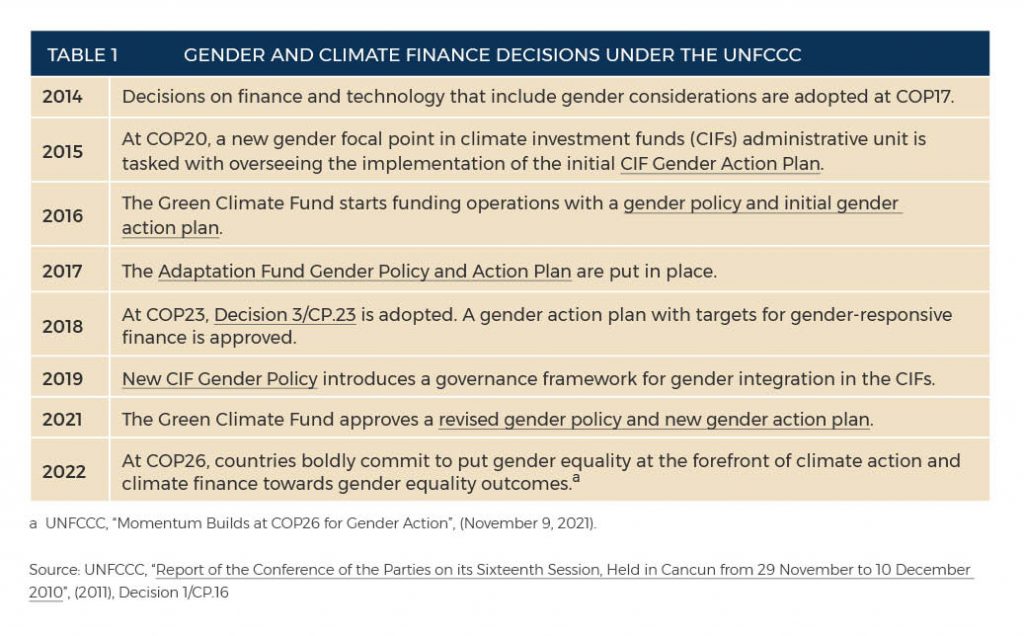

Gender is now acknowledged in several Decisions15Decisions are a type of formal action taken to record the adoption of a text representing the consensus of the Parties under the three UN climate treaties: the UNFCC (COP), the Kyoto Protocol (CMP), and the Paris Agreement (CMA). In the hierarchy of UNFCCC documents, Decisions come behind Treaties and Protocols. of the UNFCCC and climate finance as key to implementation. Table 1 highlights some key outcomes from this acknowledgment.

Despite commitments to integrate gender into climate finance, there has been no enforcement mechanism to ensure implementation.16Women Organizing for Change in Agriculture and Natural Resource Management, “Gender and Climate Finance Sourcebook: A Handbook for Building Partnerships”, October 2020; Agence Français de Développement and UN Women, “Public Development Banks Driving Gender Equality: An Overview of Practices and Measurement Frameworks”, (2021). An assessment conducted by UN Women17UN Women, “Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals the Gender Snapshot 2022”, (2022). reveals that there has been inadequate and unpredictable funding for gender equality priorities. Most climate finance is gender neutral and fails to consider genderdifferentiated impacts and responses in achieving climate action goals. A UNFCCC synthesis report, published in the run-up to COP27, highlights a growing trend towards gender integration in most updated nationally determined contributions; however, few refer to the need for gender-responsive climate finance.18UNFCCC, “Implementation of Gender-Responsive Climate Policies, Plans, Strategies and Action as Reported by Parties in Regular Reports and Communications Under the UNFCCC Process: Synthesis Report by the Secretariat”, (2022).

A study19Jenny Huang, “Equal Opportunity to Adapt: Improving Gender-Responsive Access to Climate Adaptation Financing”, (USAID & Women’s Economic Empowerment Hub: January 17, 2022). examining the gender responsiveness of climate adaptation financing finds that, while development institutions recognise the importance of gender-responsive adaptation financing, none have made major headway towards robustly mainstreaming it throughout their operations.

Existing gender equality commitments are therefore yet to enter the mainstream of policymaking and financing for climate action. Much remains to be done to ensure that climate financing is grounded in gender equality.

Barriers to mainstreaming gender in climate financing

There are several barriers that hinder the integration of gender into climate financing:20Liane Schalatek, “Gender and Climate Finance”, (Washington, DC: Heinrich Böll Stiftung, February 2022); Nancy Lee, Megan O’Donnell and Kelsey Ross, “Gender Equity in Development Finance Survey: How do Development Finance Institutions Integrate Gender Equity into their Development Finance?”, (Center for Global Development, February 2020).

- gender issues and how they interact with climate change not being well understood by many practitioners involved in climate policy and financing systems;

- lack of gender analysis to inform climate actions, which leads to gender being overlooked in climate budgets;

- limited technical capacity of gender experts to address gender issues and lack of staff training on integrating gender into climate change investments;

- gender being overlooked in financial institutions that are themselves highly gendered;

- misunderstanding of ‘gender’ and gender mainstreaming among policymakers, organisations tasked with addressing climate change and financial institutions that finance climate actions;

- lack of appreciation of gender intersectionality in existing climate financing mechanisms;

- political resistance within the climate finance system motivated by concerns that gender might take too much attention, instead of focusing on increasing the financing amounts; and

- reluctance of key players to commit to investing in gender and climate change initiatives.

A new opportunity to accelerate gender equitable climate finance

In 2020, the world’s 450 public development banks (PDBs)21PDBs are a vast family of institutions at the intersection between finance and public policy. – comprising development financial institutions, multilateral development, national and regional banks, international financing corporations, and investment and guarantee funds – gathered for the first time at the Finance in Common Summit in Paris and signed an ambitious joint declaration aimed at reorienting financial flows towards the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.22Finance in Common, “Joint Declaration of all Public Development Banks in the World”, (Paris: November 12, 2020). The banks acknowledged the slow progress towards gender equality and called for accelerated action through the international financial system. This resulted in the Paris Development Banks’ Statement on Gender Equality and Women Empowerment,23Finance in Common, “Paris Development Banks Statement on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment”, (Paris: November 12, 2020). which explicitly calls on PDBs to contribute to gender-responsive climate action.

Following the goals of the gender statement, a coalition of PDBs engaged with gender equality was launched. There are 42 PDB signatories to date.

PDBs present a pioneering opportunity to advance gender equitable climate financing and overcome the various barriers that hinder effective gender mainstreaming in climate financing. Their structure and position within the financial system enables them to play a central role in shifting financial flows towards climate actions that respond to gender inequalities. Critical to translating their commitment into concrete action are well-defined operational frameworks (policies, strategies, action plans, criteria and checklists) from the onset.

A study 24Agnes A Babugura, et al., “Walking the Talk: Insight into the Public Development Banks (PDB) Operational Frameworks for Financing Gender-Responsive Climate Action”, (forthcoming, 2023). attributes PDBs’ current flawed operational frameworks to ineffective gender mainstreaming and a lack of understanding of the gender and climate change nexus, as well as its underlying concepts. The PDBs that participated in the study for instance equated the term gender to women and girls. ‘Gender’ and ‘women’ are used interchangeably, resulting in ‘gender issues’ being framed as ‘women’s issues’. What is referred to as gender mainstreaming, in practical terms is the mainstreaming of women’s issues, which results in women-focused strategies. This has significant implications for advancing true gender equality. PDBs have an opportunity to change the status quo.

Conclusion

If PDBs are to effectively support climate actions with gender equality outcomes, there can be no ‘business as usual’ when implementing gender mainstreaming. The gender mainstreaming mantra cannot be adopted without commitment to gender equality. Gender mainstreaming was designed to be transformative, and this transformation entails tackling the root causes of gender inequality. That means going beyond treating the symptoms of gender inequality to actively examining, questioning and transforming the gender roles, power imbalances, and social norms that result in gender inequality, discrimination and exclusion. It also means redefining systems that create and perpetuate gender inequities.25Adaptation Fund, “Annex 4 to OPG: Gender Policy and Gender Action Plan”, (March 2021). It is a transformation that engages men, women, girls and boys together as agents of change.

Without challenging the underlying causes of gender inequality, gender equality will remain out of reach.

Taking gender equality seriously in climate financing therefore requires effective – and transformative – implementation of the gender mainstreaming. This will ensure greater returns on gender-transformative adaptation and mitigation investments while addressing multiple causes of gender inequality.

Acknowledgement

This policy brief is informed by a study* commissioned by the Global Development Network and funded by the French Development Agency. The study was conducted within the Finance in Common Initiative framework, as part of a broader research effort investigating the role of public development banks (PDBs) in the advancements of Sustainable Development Goals. The study aimed at investigating the PDBs’ understanding of the gender and climate change nexus, the concepts underlying the nexus, as well as identifying and assessing the operational frameworks they have in place to implement their commitment to supporting gender-responsive climate action.

[*Agnes A Babugura, Camila Vilard Duran, Mariola Acosta and Júlia Lambert Gomes Ferraz, “Walking the Talk: Insight into the Public Development Banks (PDB) Operational Frameworks for Financing Gender-Responsive Climate Action”, (forthcoming, 2023)]

SAIIA gratefully acknowledges the support of the Swedish International Development Agency for this publication.